Religion:Zhang Xun (Tang dynasty)

| Zhang Xun | |

|---|---|

| File:200px | |

| Born | 709 [1] |

| Died | November 24, 757 (age 48) |

| Occupation | General |

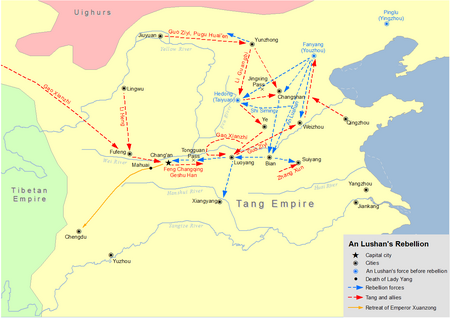

Zhang Xun (simplified Chinese: 张巡; traditional Chinese: 張巡; pinyin: Zhāng Xún) (709 – November 24, 757[2]) was a general of the Chinese Tang dynasty. He was known for defending Yongqiu and Suiyang during the An Shi Rebellion against the rebel armies of Yan, and thus, his supporters asserted, he blocked Yan forces from attacking and capturing the fertile Tang territory south of the Huai River.[3] However, he was severely criticized by some contemporaries and some later historians as lacking humanity due to his encouragement of cannibalism during the Battle of Suiyang.[4] Other historians praised him for his great faithfulness to Tang.[5]

Background

Zhang Xun was born in 709,[6] during the reign of Emperor Zhongzong of Tang. He was described as over 1.9 meters tall and had an imposing look. The official histories Old Book of Tang and New Book of Tang disagreed about the location where Zhang's family was from, with the Old Book of Tang indicating that the family was from Pu Prefecture (蒲州, roughly modern Yuncheng, Shanxi)[7] and the New Book of Tang indicating that the family was from Deng Prefecture (鄧州, roughly modern Nanyang, Henan).[6] It was said that he was studious in military strategies in his youth and had great ambitions. It was also said that he only associated with those he considered to be gentlemen, and therefore he was not well known. He passed the imperial examinations late in the Kaiyuan era (713–741) of Emperor Zhongzong's nephew Emperor Xuanzong, and initially served on the staff of Emperor Xuanzong's crown prince Li Heng before being made the magistrate of Qinghe County (清河, in modern Xingtai, Hebei). He was said to have served capably at Qinghe, and while there, paid much attention to assisting those who needed help. After his term of service was over, he returned to the Tang dynasty capital Chang'an. At that time, the governmental affairs were dominated by the chancellor Yang Guozhong, and Zhang's friends encouraged him to meet Yang to ask for another office. Zhang refused, stating that it was inappropriate for an imperial subject to be a flatterer. He later served as the magistrate of Zhenyuan County (真原, in modern Zhoukou, Henan). It was said that at that time, the large clans of the county were both powerful and treacherous, and one of the local officials from one of those clans, Hua Nanjin (華南金), was so dominant at the county government that the people often said, "What comes from Hua Nanjin's mouth is as good as what comes from the hand of the government." After Zhang arrived at Zhenyuan, he executed Hua for his abuse of power but pardoned Hua's associates, who were able to correct their ways. He also governed the county simply, and the people favored his governance.[6] His older brother Zhang Xiao (張曉) was also an imperial official, and both were known for their literary talent.[7]

During the Anshi Rebellion

Battle of Yongqiu

Late in 755, while Zhang Xun was still serving at Zhenyuan County, the general An Lushan rebelled at Fanyang Circuit (范陽, headquartered in modern Beijing) and quickly advanced south to capture the Tang eastern capital Luoyang, where he declared himself the emperor of a new state of Yan. One of his generals, Zhang Tongwu (張通晤), advanced east from Luoyang and led to the submission of a number of Tang officials, including Zhang Xun's superior Yang Wanshi (楊萬石), the governor of Qiao Commandery (譙郡, roughly modern Zhoukou). Yang forced Zhang Xun to become his secretary general and lead a delegation to welcome Zhang Tongwu. Once Zhang Xun gathered the delegation, however, instead of following Yang's orders, he led the delegation to the temple of Laozi—whom the Tang emperors considered an ancestor and posthumously honored as Emperor Xuanyuan—and led the delegation in a tearful worship of Laozi, before declaring continued loyalty to Tang and opposition against Yan. Several thousands of officials and common citizens followed him. He selected 1,000 men and took them to Yongqiu, where fellow Yan-resistor Jia Bi (賈賁) had taken up position to defend against the Tang-official-turned-Yan-general Linghu Chao (令狐潮). (Yongqiu had been Linghu's outpost when he surrendered to Yan, but once Linghu left the city on a campaign, the city turned against LInghu and submitted to Jia.) When Linghu counterattacked, Jia died in battle, and Zhang became solely in command of Tang forces in defense of Yongqiu. He sent a letter submitting to the general in command of the Tang troops in the region, Li Zhi (李祇) the Prince of Wu, and Li Zhi bestowed him the title of imperial censor to give him official command of the forces at Yongqiu.[6][7]

Linghu soon returned with a 40,000-strong Yan army, along with other Yan generals Li Huaixian, Yang Chaozong (楊朝宗), and Xie Yuantong (謝元同). Zhang Xun divided his 2,000 men into two groups—a defense group and an attack group, and as Yan forces sieged the city, he launched numerous surprise counterattacks and inflicted losses on Yan forces. Yongqiu was under siege for some 60 days, but Yan forces could not capture Yongqiu and were forced to withdraw.[8]

In spring 756, Linghu returned and put Yongqiu under siege again. During the desperate siege, six of Zhang's officers argued that they should surrender, pointing out that, by that point, Emperor Xuanzong had abandoned Chang'an and fled to Yi Prefecture (益州, roughly modern Chengdu, Sichuan). Zhang feigned agreement, and the next morning, he displayed a portrait of Emperor Xuanzong and led the soldiers in bowing to it, and then summoned the six officers and executed them. It was said that this affirmed the loyalty that the soldiers had for Tang. With Yongqiu not falling to him, Linghu was again forced to lift the siege and withdraw to Chenliu (陳留, in modern Kaifeng, Henan). Meanwhile, when another Yan general, Li Tingwang (李庭望), tried to pass Yongqiu and attack Ningling and Xiangyi (襄邑) (both in modern Shangqiu, Henan), Zhang attacked him and forced him to break off the attack on Ningling and Xiangyi.[9]

In winter 756, Linghu, along with Wang Fude (王福德), again attacked Yongqiu, but was again repelled by Zhang. However, Linghu and Li then built a new fort north of Yongqiu to cut off Yongqiu's supply lines. With several other Tang-held cities in the region falling and Yang Chaozong again ready to attack Ningling, Zhang abandoned Yongqiu and withdrew to Ningling, rendezvousing with Xu Yuan (許遠) the governor of Suiyang Commandery (睢陽, roughly modern Shangqiu) at Ningling. They repelled an attack by Yang, forcing him to flee. Zhang was subsequently made the deputy to the military governor (jiedushi) of Henan Circuit, Li Ju (李巨) the Prince of Guo (who had earlier replaced Li Zhi), but when he requested aid from Li Ju, who was then at Pengcheng, Li Ju refused to provide material aid, only commissioning Zhang's subordinates with official titles.[10]

By this point, An Lushan had been assassinated and replaced as the emperor of Yan by his son An Qingxu. After An Qingxu took the throne, he sent the general Yin Ziqi (尹子奇) to attack Suiyang (i.e., the capital of Suiyang Commandery). Xu, who had returned to Suiyang by that point, sought aid from Zhang. Zhang therefore left his officer Lian Tan (廉坦) in charge of defending Ningling and took most of his forces to Suiyang, defending the city together. They repelled Yin's attack initially, but Yin soon regrouped and put Suiyang under siege. Xu, citing the fact that he was a civilian official and not well versed in military matters, bestowed the command of their joint forces on Zhang and became only responsible for logistics, leaving the military matters to Zhang.[10]

Battle of Suiyang

Yin Ziqi launched repeated attacks on Suiyang, each time repelled by Zhang Xun. Meanwhile, though, the food supplies—which Xu Yuan had initially gathered plenty of in anticipation of a siege but which Li Ju had forced Xu to partially give to two other commanderies, Puyang (濮陽, roughly modern Puyang, Henan) and Jiyin (濟陰, roughly modern Heze, Shandong)—began to run out. By summer 757, Suiyang was in desperate straits, with the soldiers forced to eat a mixture of rice, tea leaves, paper, and bark. Many suffered from illnesses. Despite this, Zhang continued to fight off attack after attack. He also divided the defense zones with Xu, with him defending the northeast side and Xu defending the southwest side, both spending the days and nights with the soldiers in defending the city. He often called out to the Yan troops, trying to persuade them that the Tang cause was righteous, and it was said that often, Yan soldiers would be touched by his words and surrender and join his troops.[10]

Zhang made one desperate attempt to seek aid. He gave his officer Nan Jiyun (南霽雲) 30 cavalry soldiers and had Nan fight his way out of the siege, to head to Linhuai (臨淮, in modern Huai'an, Jiangsu) to seek aid from the Tang general Helan Jinming (賀蘭進明), who had the strongest Tang force in the area. When Nan arrived at Linhuai, however, Helan refused to render aid—believing that by the time that he arrived at Suiyang, Suiyang would have fallen already and he would have merely put his own army at risk. (Historical accounts also indicated that Helan was jealous of Zhang and Xu, and also feared attacks from another Tang general, Xu Shuji (許叔冀), an ally of the chancellor Fang Guan, to whom Helan was a political enemy.) Instead, Helan tried to keep Nan on his staff, and Nan refused. He headed for Ningling and joined forces with Lian Tan and 3,000 men, then headed back toward Suiyang. However, when they arrived back at Suiyang and fought their way back into the city, they suffered heavy losses, and only 1,000 troops survived to join the garrison.[10]

Zhang's officers urged him to consider abandoning Suiyang and fleeing east. Zhang and Xu discussed the proposal, but eventually decided to keep defending the city, believing that abandoning Suiyang would allow Yan forces to attack and capture the region between the Huai River and the Yangtze River, and that given how weak their troops were, they could not escape disaster even if they abandoned Suiyang. However, the food supplies further ran out, and they began to have to kill their warhorses for food. After the horses were gone, they ate sparrows and rats. Eventually, Zhang killed his beloved concubine and let the soldiers eat her body. Xu then killed his servants for food as well, followed by the women in the city, and then the non-abled body men. It was said that although everyone knew that he or she would die, no one resisted. Eventually, only 400 people remained in the city.[11]

Death and posthumous recognitions

On November 24, 757,[2] Yan forces scaled the walls of the city, and the Tang forces were unable to fight them off. Suiyang thus fell, and Zhang Xun and Xu Yuan were captured. Yin Ziqi admired Zhang and wanted to spare his life, but Yin's subordinates believed that allowing Zhang to stay alive could potentially foster a mutiny. Yin therefore executed Zhang and 36 key officers under him, including Nan Jiyun and Lei Wanchun (雷萬春). Xu was to be delivered to Luoyang, but on the way to Luoyang, Yan soldiers heard that allied Tang and Huige forces commanded by Li Chu the Prince of Chu (the son of Emperor Xuanzong's son Emperor Suzong, who had assumed the throne in the confusion of the Anshi Rebellion) had captured Luoyang, and they killed Xu at Yanshi (偃師, near Luoyang).[11]

After Emperor Suzong returned to Chang'an, he posthumously honored a large number of officials who stayed faithful to Tang and died fighting the Yan forces. However, the matter of whether to honor Zhang and Xu became an immediately controversial matter due to the cannibalism that had occurred at Suiyang. A friend of Zhang's, Li Han, wrote a biography of Zhang's in an impassioned defense of Zhang, arguing that without Zhang's actions, Tang would have lost the war entirely.[11] Li Han was joined in his opinion by several other officials, including Li Shu (李紓), Dong Nanshi (董南史), Zhang Jianfeng Fan Huang (樊晃), and Zhu Juchuan (朱巨川). Emperor Suzong accepted their defense of Zhang's, and honored Zhang, Xu, and Nan in particular, as well as the other officers who died in the siege. He also gave their families great rewards.[6]

A temple was built at Suiyang to honor Zhang and Xu, known as the Double Temple (雙廟, Shuang Miao).[6] The pair also sometimes appear as door gods in Chinese and Taoist temples.

Historical views

Zhang Xun and his deeds were highly praised by many later scholars, government officials, and writers. For example, the Song dynasty official Wen Tianxiang, who was himself greatly praised for his faithfulness to Song and refusal to submit to the Yuan dynasty, listed Zhang in his Song of Righteousness (Zhengqige, 正氣歌) as one of the persons to admire for their righteousness.[12] However, some, including the Qing dynasty scholar Wang Fuzhi, severely criticized him for not only permitting but encouraging cannibalism,[4] and some others, such as the modern historian Bo Yang, while not as critical, nevertheless pointed out the lamentable nature of Zhang's actions.[13]

References

Citations

- ↑ Zhang's biography in volume 192 of New Book of Tang recorded that he was 49 (by East Asian reckoning) when he died. By calculation, his birth year should be 709.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Volume 220 of Zizhi Tongjian recorded that Zhang was executed on the guichou day of the 10th month of the 2nd year of the Zhide era of Tang Suzong's reign. This date corresponds to 24 Nov 757 on the Gregorian calendar.

- ↑ See, e.g., the defense of Zhang Xun by Li Han (李翰) cited in the Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 220.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 See, Wang Fuzhi's criticism, cited in the Bo Yang Edition of the Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 53 [757].

- ↑ See, e.g., Old Book of Tang, vol. 187, part 2 [listing Zhang among the "faithful and righteous"] and New Book of Tang, vol. 192 [same].

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 New Book of Tang, vol. 192.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Old Book of Tang, vol. 187, part 2.

- ↑ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 217.

- ↑ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 218.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 219.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 220.

- ↑ Wen Tianxiang, Song of Righteousness.

- ↑ Bo Yang Edition of the Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 53 [757].

Bibliography

- Old Book of Tang, vol. 187, part 2.

- New Book of Tang, vol. 192.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vols. 217, 218, 219, 220.

|