Rete algorithm

The Rete algorithm (/ˈriːtiː/ REE-tee, /ˈreɪtiː/ RAY-tee, rarely /ˈriːt/ REET, /rɛˈteɪ/ reh-TAY) is a pattern matching algorithm for implementing rule-based systems. The algorithm was developed to efficiently apply many rules or patterns to many objects, or facts, in a knowledge base. It is used to determine which of the system's rules should fire based on its data store, its facts. The Rete algorithm was designed by Charles L. Forgy of Carnegie Mellon University, first published in a working paper in 1974, and later elaborated in his 1979 Ph.D. thesis and a 1982 paper.[1]

Overview

A naive implementation of an expert system might check each rule against known facts in a knowledge base, firing that rule if necessary, then moving on to the next rule (and looping back to the first rule when finished). For even moderate sized rules and facts knowledge-bases, this naive approach performs far too slowly. The Rete algorithm provides the basis for a more efficient implementation. A Rete-based expert system builds a network of nodes, where each node (except the root) corresponds to a pattern occurring in the left-hand-side (the condition part) of a rule. The path from the root node to a leaf node defines a complete rule left-hand-side. Each node has a memory of facts that satisfy that pattern. This structure is essentially a generalized trie. As new facts are asserted or modified, they propagate along the network, causing nodes to be annotated when that fact matches that pattern. When a fact or combination of facts causes all of the patterns for a given rule to be satisfied, a leaf node is reached and the corresponding rule is triggered.

Rete was first used as the core engine of the OPS5 production system language, which was used to build early systems including R1 for Digital Equipment Corporation. Rete has become the basis for many popular rule engines and expert system shells, including CLIPS, Jess, Drools, IBM Operational Decision Management, BizTalk Rules Engine, Soar, and Evrete. The word 'Rete' is Latin for 'net' or 'comb'. The same word is used in modern Italian to mean 'network'. Charles Forgy has reportedly stated that he adopted the term 'Rete' because of its use in anatomy to describe a network of blood vessels and nerve fibers.[2]

The Rete algorithm is designed to sacrifice memory for increased speed. In most cases, the speed increase over naïve implementations is several orders of magnitude (because Rete performance is theoretically independent of the number of rules in the system). In very large expert systems, however, the original Rete algorithm tends to run into memory and server consumption problems. Other algorithms, both novel and Rete-based, have since been designed that require less memory (e.g. Rete*[3] or Collection Oriented Match[4]).

Description

The Rete algorithm provides a generalized logical description of an implementation of functionality responsible for matching data tuples ("facts") against productions ("rules") in a pattern-matching production system (a category of rule engine). A production consists of one or more conditions and a set of actions that may be undertaken for each complete set of facts that match the conditions. Conditions test fact attributes, including fact type specifiers/identifiers. The Rete algorithm exhibits the following major characteristics:

- It reduces or eliminates certain types of redundancy through the use of node sharing.

- It stores partial matches when performing joins between different fact types. This, in turn, allows production systems to avoid complete re-evaluation of all facts each time changes are made to the production system's working memory. Instead, the production system needs only to evaluate the changes (deltas) to working memory.

- It allows for efficient removal of memory elements when facts are retracted from working memory.

The Rete algorithm is widely used to implement matching functionality within pattern-matching engines that exploit a match-resolve-act cycle to support forward chaining and inferencing.

- It provides a means for many–many matching, an important feature when many or all possible solutions in a search network must be found.

Retes are directed acyclic graphs that represent higher-level rule sets. They are generally represented at run-time using a network of in-memory objects. These networks match rule conditions (patterns) to facts (relational data tuples). Rete networks act as a type of relational query processor, performing projections, selections and joins conditionally on arbitrary numbers of data tuples.

Productions (rules) are typically captured and defined by analysts and developers using some high-level rules language. They are collected into rule sets that are then translated, often at run time, into an executable Rete.

When facts are "asserted" to working memory, the engine creates working memory elements (WMEs) for each fact. Facts are tuples, and may therefore contain an arbitrary number of data items. Each WME may hold an entire tuple, or, alternatively, each fact may be represented by a set of WMEs where each WME contains a fixed-length tuple. In this case, tuples are typically triplets (3-tuples).

Each WME enters the Rete network at a single root node. The root node passes each WME on to its child nodes, and each WME may then be propagated through the network, possibly being stored in intermediate memories, until it arrives at a terminal node.

Alpha network

The "left" (alpha) side of the node graph forms a discrimination network responsible for selecting individual WMEs based on simple conditional tests that match WME attributes against constant values. Nodes in the discrimination network may also perform tests that compare two or more attributes of the same WME. If a WME is successfully matched against the conditions represented by one node, it is passed to the next node. In most engines, the immediate child nodes of the root node are used to test the entity identifier or fact type of each WME. Hence, all the WMEs that represent the same entity type typically traverse a given branch of nodes in the discrimination network.

Within the discrimination network, each branch of alpha nodes (also called 1-input nodes) terminates at a memory, called an alpha memory. These memories store collections of WMEs that match each condition in each node in a given node branch. WMEs that fail to match at least one condition in a branch are not materialised within the corresponding alpha memory. Alpha node branches may fork in order to minimise condition redundancy.

Beta network

The "right" (beta) side of the graph chiefly performs joins between different WMEs. It is optional, and is only included if required. It consists of 2-input nodes where each node has a "left" and a "right" input. Each beta node sends its output to a beta memory.

In descriptions of Rete, it is common to refer to token passing within the beta network. In this article, however, we will describe data propagation in terms of WME lists, rather than tokens, in recognition of different implementation options and the underlying purpose and use of tokens. As any one WME list passes through the beta network, new WMEs may be added to it, and the list may be stored in beta memories. A WME list in a beta memory represents a partial match for the conditions in a given production.

WME lists that reach the end of a branch of beta nodes represent a complete match for a single production, and are passed to terminal nodes. These nodes are sometimes called p-nodes, where "p" stands for production. Each terminal node represents a single production, and each WME list that arrives at a terminal node represents a complete set of matching WMEs for the conditions in that production. For each WME list it receives, a production node will "activate" a new production instance on the "agenda". Agendas are typically implemented as prioritised queues.

Beta nodes typically perform joins between WME lists stored in beta memories and individual WMEs stored in alpha memories. Each beta node is associated with two input memories. An alpha memory holds WM and performs "right" activations on the beta node each time it stores a new WME. A beta memory holds WME lists and performs "left" activations on the beta node each time it stores a new WME list. When a join node is right-activated, it compares one or more attributes of the newly stored WME from its input alpha memory against given attributes of specific WMEs in each WME list contained in the input beta memory. When a join node is left-activated it traverses a single newly stored WME list in the beta memory, retrieving specific attribute values of given WMEs. It compares these values with attribute values of each WME in the alpha memory.

Each beta node outputs WME lists that are either stored in a beta memory or sent directly to a terminal node. WME lists are stored in beta memories whenever the engine will perform additional left activations on subsequent beta nodes.

Logically, a beta node at the head of a branch of beta nodes is a special case because it takes no input from any beta memory higher in the network. Different engines handle this issue in different ways. Some engines use specialised adapter nodes to connect alpha memories to the left input of beta nodes. Other engines allow beta nodes to take input directly from two alpha memories, treating one as a "left" input and the other as a "right" input. In both cases, "head" beta nodes take their input from two alpha memories.

In order to eliminate node redundancies, any one alpha or beta memory may be used to perform activations on multiple beta nodes. As well as join nodes, the beta network may contain additional node types, some of which are described below. If a Rete contains no beta network, alpha nodes feed tokens, each containing a single WME, directly to p-nodes. In this case, there may be no need to store WMEs in alpha memories.

Conflict resolution

During any one match-resolve-act cycle, the engine will find all possible matches for the facts currently asserted to working memory. Once all the current matches have been found, and corresponding production instances have been activated on the agenda, the engine determines an order in which the production instances may be "fired". This is termed conflict resolution, and the list of activated production instances is termed the conflict set. The order may be based on rule priority (salience), rule order, the time at which facts contained in each instance were asserted to the working memory, the complexity of each production, or some other criteria. Many engines allow rule developers to select between different conflict resolution strategies or to chain a selection of multiple strategies.

Conflict resolution is not defined as part of the Rete algorithm, but is used alongside the algorithm. Some specialised production systems do not perform conflict resolution.

Production execution

Having performed conflict resolution, the engine now "fires" the first production instance, executing a list of actions associated with the production. The actions act on the data represented by the production instance's WME list.

By default, the engine will continue to fire each production instance in order until all production instances have been fired. Each production instance will fire only once, at most, during any one match-resolve-act cycle. This characteristic is termed refraction. However, the sequence of production instance firings may be interrupted at any stage by performing changes to the working memory. Rule actions can contain instructions to assert or retract WMEs from the working memory of the engine. Each time any single production instance performs one or more such changes, the engine immediately enters a new match-resolve-act cycle. This includes "updates" to WMEs currently in the working memory. Updates are represented by retracting and then re-asserting the WME. The engine undertakes matching of the changed data which, in turn, may result in changes to the list of production instances on the agenda. Hence, after the actions for any one specific production instance have been executed, previously activated instances may have been de-activated and removed from the agenda, and new instances may have been activated.

As part of the new match-resolve-act cycle, the engine performs conflict resolution on the agenda and then executes the current first instance. The engine continues to fire production instances, and to enter new match-resolve-act cycles, until no further production instances exist on the agenda. At this point the rule engine is deemed to have completed its work, and halts.

Some engines support advanced refraction strategies in which certain production instances executed in a previous cycle are not re-executed in the new cycle, even though they may still exist on the agenda.

It is possible for the engine to enter into never-ending loops in which the agenda never reaches the empty state. For this reason, most engines support explicit "halt" verbs that can be invoked from production action lists. They may also provide automatic loop detection in which never-ending loops are automatically halted after a given number of iterations. Some engines support a model in which, instead of halting when the agenda is empty, the engine enters a wait state until new facts are asserted externally.

As for conflict resolution, the firing of activated production instances is not a feature of the Rete algorithm. However, it is a central feature of engines that use Rete networks. Some of the optimisations offered by Rete networks are only useful in scenarios where the engine performs multiple match-resolve-act cycles.

Existential and universal quantifications

Conditional tests are most commonly used to perform selections and joins on individual tuples. However, by implementing additional beta node types, it is possible for Rete networks to perform quantifications. Existential quantification involves testing for the existence of at least one set of matching WMEs in working memory. Universal quantification involves testing that an entire set of WMEs in working memory meets a given condition. A variation of universal quantification might test that a given number of WMEs, drawn from a set of WMEs, meets given criteria. This might be in terms of testing for either an exact number or a minimum number of matches.

Quantification is not universally implemented in Rete engines, and, where it is supported, several variations exist. A variant of existential quantification referred to as negation is widely, though not universally, supported, and is described in seminal documents. Existentially negated conditions and conjunctions involve the use of specialised beta nodes that test for non-existence of matching WMEs or sets of WMEs. These nodes propagate WME lists only when no match is found. The exact implementation of negation varies. In one approach, the node maintains a simple count on each WME list it receives from its left input. The count specifies the number of matches found with WMEs received from the right input. The node only propagates WME lists whose count is zero. In another approach, the node maintains an additional memory on each WME list received from the left input. These memories are a form of beta memory, and store WME lists for each match with WMEs received on the right input. If a WME list does not have any WME lists in its memory, it is propagated down the network. In this approach, negation nodes generally activate further beta nodes directly, rather than storing their output in an additional beta memory. Negation nodes provide a form of 'negation as failure'.

When changes are made to working memory, a WME list that previously matched no WMEs may now match newly asserted WMEs. In this case, the propagated WME list and all its extended copies need to be retracted from beta memories further down the network. The second approach described above is often used to support efficient mechanisms for removal of WME lists. When WME lists are removed, any corresponding production instances are de-activated and removed from the agenda.

Existential quantification can be performed by combining two negation beta nodes. This represents the semantics of double negation (e.g., "If NOT NOT any matching WMEs, then..."). This is a common approach taken by several production systems.

Memory indexing

The Rete algorithm does not mandate any specific approach to indexing the working memory. However, most modern production systems provide indexing mechanisms. In some cases, only beta memories are indexed, whilst in others, indexing is used for both alpha and beta memories. A good indexing strategy is a major factor in deciding the overall performance of a production system, especially when executing rule sets that result in highly combinatorial pattern matching (i.e., intensive use of beta join nodes), or, for some engines, when executing rules sets that perform a significant number of WME retractions during multiple match-resolve-act cycles. Memories are often implemented using combinations of hash tables, and hash values are used to perform conditional joins on subsets of WME lists and WMEs, rather than on the entire contents of memories. This, in turn, often significantly reduces the number of evaluations performed by the Rete network.

Removal of WMEs and WME lists

When a WME is retracted from working memory, it must be removed from every alpha memory in which it is stored. In addition, WME lists that contain the WME must be removed from beta memories, and activated production instances for these WME lists must be de-activated and removed from the agenda. Several implementation variations exist, including tree-based and rematch-based removal. Memory indexing may be used in some cases to optimise removal.

Handling ORed conditions

When defining productions in a rule set, it is common to allow conditions to be grouped using an OR connective. In many production systems, this is handled by interpreting a single production containing multiple ORed patterns as the equivalent of multiple productions. The resulting Rete network contains sets of terminal nodes which, together, represent single productions. This approach disallows any form of short-circuiting of the ORed conditions. It can also, in some cases, lead to duplicate production instances being activated on the agenda where the same set of WMEs match multiple internal productions. Some engines provide agenda de-duplication in order to handle this issue.

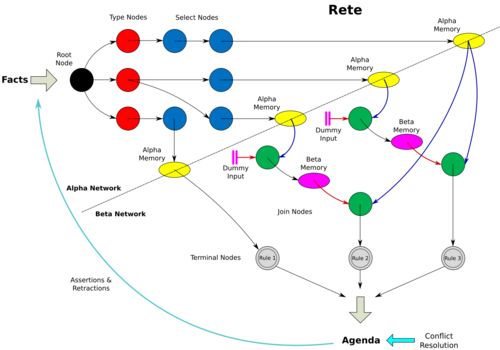

Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the basic Rete topology, and shows the associations between different node types and memories.

- Most implementations use type nodes to perform the first level of selection on tuple working memory elements. Type nodes can be considered as specialized select nodes. They discriminate between different tuple relation types.

- The diagram does not illustrate the use of specialized nodes types such as negated conjunction nodes. Some engines implement several different node specialisations in order to extend functionality and maximise optimisation.

- The diagram provides a logical view of the Rete. Implementations may differ in physical detail. In particular, the diagram shows dummy inputs providing right activations at the head of beta node branches. Engines may implement other approaches, such as adapters that allow alpha memories to perform right activations directly.

- The diagram does not illustrate all node-sharing possibilities.

For a more detailed and complete description of the Rete algorithm, see chapter 2 of Production Matching for Large Learning Systems by Robert Doorenbos (see link below).

Alternatives

Alpha Network

A possible variation is to introduce additional memories for each intermediate node in the discrimination network. This increases the overhead of the Rete, but may have advantages in situations where rules are dynamically added to or removed from the Rete, making it easier to vary the topology of the discrimination network dynamically.

An alternative implementation is described by Doorenbos.[5] In this case, the discrimination network is replaced by a set of memories and an index. The index may be implemented using a hash table. Each memory holds WMEs that match a single conditional pattern, and the index is used to reference memories by their pattern. This approach is only practical when WMEs represent fixed-length tuples, and the length of each tuple is short (e.g., 3-tuples). In addition, the approach only applies to conditional patterns that perform equality tests against constant values. When a WME enters the Rete, the index is used to locate a set of memories whose conditional pattern matches the WME attributes, and the WME is then added directly to each of these memories. In itself, this implementation contains no 1-input nodes. However, in order to implement non-equality tests, the Rete may contain additional 1-input node networks through which WMEs are passed before being placed in a memory. Alternatively, non-equality tests may be performed in the beta network described below.

Beta Network

A common variation is to build linked lists of tokens where each token holds a single WME. In this case, lists of WMEs for a partial match are represented by the linked list of tokens. This approach may be better because it eliminates the need to copy lists of WMEs from one token to another. Instead, a beta node needs only to create a new token to hold a WME it wishes to join to the partial match list, and then link the new token to a parent token stored in the input beta memory. The new token now forms the head of the token list, and is stored in the output beta memory.

Beta nodes process tokens. A token is a unit of storage within a memory and also a unit of exchange between memories and nodes. In many implementations, tokens are introduced within alpha memories where they are used to hold single WMEs. These tokens are then passed to the beta network.

Each beta node performs its work and, as a result, may create new tokens to hold a list of WMEs representing a partial match. These extended tokens are then stored in beta memories, and passed to subsequent beta nodes. In this case, the beta nodes typically pass lists of WMEs through the beta network by copying existing WME lists from each received token into new tokens and then adding further WMEs to the lists as a result of performing a join or some other action. The new tokens are then stored in the output memory.

Miscellaneous considerations

Although not defined by the Rete algorithm, some engines provide extended functionality to support greater control of truth maintenance. For example, when a match is found for one production, this may result in the assertion of new WMEs which, in turn, match the conditions for another production. If a subsequent change to working memory causes the first match to become invalid, it may be that this implies that the second match is also invalid. The Rete algorithm does not define any mechanism to define and handle these logical truth dependencies automatically. Some engines, however, support additional functionality in which truth dependencies can be automatically maintained. In this case, the retraction of one WME may lead to the automatic retraction of additional WMEs in order to maintain logical truth assertions.

The Rete algorithm does not define any approach to justification. Justification refers to mechanisms commonly required in expert and decision systems in which, at its simplest, the system reports each of the inner decisions used to reach some final conclusion. For example, an expert system might justify a conclusion that an animal is an elephant by reporting that it is large, grey, has big ears, a trunk and tusks. Some engines provide built-in justification systems in conjunction with their implementation of the Rete algorithm.

This article does not provide an exhaustive description of every possible variation or extension of the Rete algorithm. Other considerations and innovations exist. For example, engines may provide specialised support within the Rete network in order to apply pattern-matching rule processing to specific data types and sources such as programmatic objects, XML data or relational data tables. Another example concerns additional time-stamping facilities provided by many engines for each WME entering a Rete network, and the use of these time-stamps in conjunction with conflict resolution strategies. Engines exhibit significant variation in the way they allow programmatic access to the engine and its working memory, and may extend the basic Rete model to support forms of parallel and distributed processing.

Optimization and performance

Several optimizations for Rete have been identified and described in academic literature. Several of these, however, apply only in very specific scenarios, and therefore often have little or no application in a general-purpose rules engine. In addition, alternative algorithms such as TREAT, developed by Daniel P. Miranker[6] LEAPS, and Design Time Inferencing (DeTI) have been formulated that may provide additional performance improvements.

The Rete algorithm is suited to scenarios where forward chaining and "inferencing" is used to calculate new facts from existing facts, or to filter and discard facts in order to arrive at some conclusion. It is also exploited as a reasonably efficient mechanism for performing highly combinatorial evaluations of facts where large numbers of joins must be performed between fact tuples. Other approaches to performing rule evaluation, such as the use of decision trees, or the implementation of sequential engines, may be more appropriate for simple scenarios, and should be considered as possible alternatives.

Performance of Rete is also largely a matter of implementation choices (independent of the network topology), one of which (the use of hash tables) leads to major improvements. Most of the performance benchmarks and comparisons available on the web are biased in some way or another. To mention only a frequent bias and an unfair type of comparison: 1) the use of toy problems such as the Manners and Waltz examples; such examples are useful to estimate specific properties of the implementation, but they may not reflect real performance on complex applications; 2) the use of an old implementation; for instance, the references in the following two sections (Rete II and Rete-NT) compare some commercial products to totally outdated versions of CLIPS and they claim that the commercial products may be orders of magnitude faster than CLIPS; this is forgetting that CLIPS 6.30 (with the introduction of hash tables as in Rete II) is orders of magnitude faster than the version used for the comparisons (CLIPS 6.04).

Variants

Rete II

In the 1980s, Charles Forgy developed a successor to the Rete algorithm named Rete II.[7] Unlike the original Rete (which is public domain) this algorithm was not disclosed. Rete II claims better performance for more complex problems (even orders of magnitude[8]), and is officially implemented in CLIPS/R2, a C/++ implementation and in OPSJ, a Java implementation in 1998. Rete II gives about a 100 to 1 order of magnitude performance improvement in more complex problems as shown by KnowledgeBased Systems Corporation[9] benchmarks.

Rete II can be characterized by two areas of improvement; specific optimizations relating to the general performance of the Rete network (including the use of hashed memories in order to increase performance with larger sets of data), and the inclusion of a backward chaining algorithm tailored to run on top of the Rete network. Backward chaining alone can account for the most extreme changes in benchmarks relating to Rete vs. Rete II. Rete II is implemented in the commercial product Advisor from FICO, formerly called Fair Isaac [10]

Jess (at least versions 5.0 and later) also adds a commercial backward chaining algorithm on top of the Rete network, but it cannot be said to fully implement Rete II, in part due to the fact that no full specification is publicly available.

Rete-III

In the early 2000s, the Rete III engine was developed by Charles Forgy in cooperation with FICO engineers. The Rete III algorithm, which is not Rete-NT, is the FICO trademark for Rete II and is implemented as part of the FICO Advisor engine. It is basically the Rete II engine with an API that allows access to the Advisor engine because the Advisor engine can access other FICO products.[11]

Rete-NT

In 2010, Forgy developed a new generation of the Rete algorithm. In an InfoWorld benchmark, the algorithm was deemed 500 times faster than the original Rete algorithm and 10 times faster than its predecessor, Rete II.[12] This algorithm is now licensed to Sparkling Logic, the company that Forgy joined as investor and strategic advisor,[13][14] as the inference engine of the SMARTS product.

Rete-OO

Considering that Rete aims to support first-order logic (basically if-then-else statements), Rete-OO[15] aims to provide a rule-based system that supports uncertainty (where the information to make a decision is missing or is inaccurate). According to the author's proposal, the rule "if Danger then Alarm" would be improved to something such as "given the probability of Danger, there will be a certain probability of hearing an Alarm" or even "the greater the Danger, the louder should be Alarm". For this it extends the Drools language (which already implements the Rete algorithm) to make it support probabilistic logic, like fuzzy logic and Bayesian networks.

See also

- Action selection mechanism

- Inference engine

References

- ↑ Charles, Forgy (1982). "Rete: A Fast Algorithm for the Many Pattern/Many Object Pattern Match Problem". Artificial Intelligence 19: 17–37. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(82)90020-0.

- ↑ "Rete Algorithm Demystified! – Part 1" by Carole-Ann Matignon

- ↑ "The Execution Kernel of RC++: RETE* A Faster Rete with TREAT as a Special Case" (in en-gb). http://www.cs.bris.ac.uk/Publications/Papers/2000091.pdf.

- ↑ Anurag Acharya; Milind Tambe (1993). "Collection Oriented Match". Proceedings of the second international conference on Information and knowledge management - CIKM '93. CIKM '93 Proceedings of the second international conference on Information and knowledge management. pp. 516–526. doi:10.1145/170088.170411. ISBN 0897916263. http://teamcore.usc.edu/papers/1993/cikm-final.pdf.

- ↑ Production Matching for Large Learning Systems from SCS Technical Report Collection, School of Computer Science, Carnegie Mellon University

- ↑ http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=39946 "TREAT: a new and efficient match algorithm for AI production systems "

- ↑ RETE2 from Production Systems Technologies

- ↑ Benchmarking CLIPS/R2 from Production Systems Technologies

- ↑ KBSC

- ↑ "What is Rete III? - Decision Management Blog". http://dmblog.fico.com/2005/09/what_is_rete_ii.html.

- ↑ "What is Rete III? - Decision Management Blog". http://dmblog.fico.com/2005/09/what_is_rete_ii.html.

- ↑ Owen, James (2010-09-20). "World's fastest rules engine | Business rule management systems". InfoWorld. http://www.infoworld.com/t/business-rule-management-systems/worlds-fastest-rules-engine-822. Retrieved 2012-04-07.

- ↑ "It's Official, Dr. Charles Forgy Joins Sparkling Logic as Strategic Advisor". PR.com. 2011-10-31. http://www.pr.com/press-release/365279.

- ↑ "Dr. Charles Forgy, PhD". www.sparklinglogic.com. http://www.sparklinglogic.com/advisors/.

- ↑ Sottara, Davide; Mello, Paola; Proctor, Mark (2010). "A Configurable Rete-OO Engine for Reasoning with Different Types of Imperfect Information" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Knowledge and Data Engineering 22 (11): 1535–1548. doi:10.1109/TKDE.2010.125. Bibcode: 2010ITKDE..22.1535S. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.713.3826&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Retrieved 2022-01-10.

External links

- Rete Algorithm explained Bruce Schneier, Dr. Dobb's Journal

- Production Matching for Large Learning Systems – R Doorenbos Detailed and accessible description of Rete, also describes a variant named Rete/UL, optimised for large systems (PDF)

- According to the Rules (A short introduction from cut-the-knot)

|