Russian phonology

This article discusses the phonological system of standard Russian based on the Moscow dialect (unless otherwise noted). For an overview of dialects in the Russian language, see Russian dialects. Most descriptions of Russian describe it as having five vowel phonemes, though there is some dispute over whether a sixth vowel, [ɨ], is separate from /i/. Russian has 34 consonants, which can be divided into two types:

- hard (твёрдый

[ˈtvʲɵrdɨj] (help·info)) or plain

[ˈtvʲɵrdɨj] (help·info)) or plain - soft (мягкий

[ˈmʲæxʲkʲɪj]) or palatalized

[ˈmʲæxʲkʲɪj]) or palatalized

Russian also distinguishes hard consonants from soft (palatalized) consonants and from consonants followed by /j/, making four sets in total: /C Cʲ Cj Cʲj/, although /Cj/ in native words appears only at morpheme boundaries. Russian also preserves palatalized consonants that are followed by another consonant more often than other Slavic languages do. Like Polish, it has both hard postalveolars (/ʂ ʐ/) and soft ones (/tɕ ɕː ʑː/).

Russian has vowel reduction in unstressed syllables. This feature also occurs in a minority of other Slavic languages like Belarusian and Bulgarian, and is also found in English, but not in most other Slavic languages, such as Czech, Polish and most varieties of Serbo-Croatian.

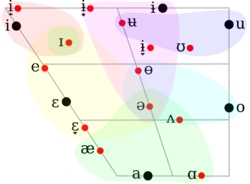

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | (ɨ) | u |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

Russian has five to six vowels in stressed syllables, /i, u, e, o, a/ and in some analyses /ɨ/, but in most cases these vowels have merged to only two to four vowels when unstressed: /i, u, a/ (or /ɨ, u, a/) after hard consonants and /i, u/ after soft ones.

A long-standing dispute among linguists is whether Russian has five vowel phonemes or six; that is, scholars disagree as to whether [ɨ] constitutes an allophone of /i/ or if there is an independent phoneme /ɨ/. The five-vowel analysis, taken up by the Moscow school, rests on the complementary distribution of [ɨ] and [i], with the former occurring after hard (non-palatalized) consonants and [i] elsewhere. The allophony of the stressed variant of the open /a/ is largely the same, yet no scholar considers [ä] and [æ] to be separate phonemes (which they are in e.g. Slovak).

The six-vowel view, held by the Saint-Petersburg (Leningrad) phonology school, points to several phenomena to make its case:

- Native Russian speakers' ability to articulate [ɨ] in isolation: for example, in the names of the letters ⟨и⟩ and ⟨ы⟩.[1]

- Rare instances of word-initial [ɨ], including the minimal pair и́кать 'to produce the sound и' and ы́кать 'to produce the sound ы'),[2] as well as borrowed names and toponyms, like Ыб

[ɨp] (help·info), the name of a river and several villages in the Komi Republic.

[ɨp] (help·info), the name of a river and several villages in the Komi Republic. - Morphological alternations like гото́в

[ɡʌˈtof] ('ready' predicate, m.) and гото́вить

[ɡʌˈtof] ('ready' predicate, m.) and гото́вить  [ɡʌˈtɵvʲɪtʲ] ('to get ready' trans.) between palatalized and non-palatalized consonants.[3]

[ɡʌˈtɵvʲɪtʲ] ('to get ready' trans.) between palatalized and non-palatalized consonants.[3]

The most popular view among linguists (and that taken up in this article) is that of the Moscow school,[2] though Russian pedagogy has typically taught that there are six vowels (the term phoneme is not used).[4]

Reconstructions of Proto-Slavic show that *i and *y (which correspond to [i] and [ɨ]) were separate phonemes. On the other hand, numerous alternations between the two sounds in Russian indicate clearly that at one point the two sounds were reanalyzed as allophones of each other.

Allophony

| Phoneme | Letter (typically) |

Position | Stressed | Reduced |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| /i/ | и | (Cʲ)V(C) | [i] | [ɪ] |

| ы, и | (C)V | [ɨ] | ||

| /u/ | у | (C)V | [u] | [ʊ] |

| (C)VCʲ | ||||

| ю | CʲV | [ʉ] | ||

| /e/ | э | VC | [ɛ] | [ɪ] |

| е | CʲV | [e] | ||

| э, е† | CVC | [ɛ] | [ɨ] | |

| CVCʲ | [e] | |||

| /o/ | о | (C)V | [o] | [ə], [ʌ] |

| (C)VCʲ | [ɵ] | |||

| ё* | CʲV | [ɪ] | ||

| /a/ | а | (C)V | [ä] | [ə], [ʌ] |

| (C)VCʲ | ||||

| я | CʲV | [æ] | [ɪ] | |

| ||||

Russian vowels are subject to considerable allophony, subject to both stress and the palatalization of neighboring consonants. In most unstressed positions, in fact, only three phonemes are distinguished after hard consonants, and only two after soft consonants. Unstressed /o/ and /a/ have merged to /a/ (a phenomenon known as Russian: а́канье); unstressed /i/ and /e/ have merged to /i/ (Russian: и́канье); and all four unstressed vowels have merged after soft consonants, except in absolute final position in a word. None of these mergers are represented in writing.

Front vowels

When a preceding consonant is hard, /i/ is retracted to [ɨ]. Formant studies in Padgett (2001) demonstrate that [ɨ] is better characterized as slightly diphthongized from the velarization of the preceding consonant,[5] implying that a phonological pattern of using velarization to enhance perceptual distinctiveness between hard and soft consonants is strongest before /i/. When unstressed, /i/ becomes near-close; that is, [ɨ̞] following a hard consonant and [ɪ] in most other environments.[6] Between soft consonants, stressed /i/ is raised,[7] as in пить ![]() [pʲi̝tʲ] (help·info) ('to drink'). When preceded and followed by coronal or dorsal consonants, [ɨ] is fronted to [ɨ̟].[8] After a cluster of a labial and /ɫ/, [ɨ] is retracted, as in плыть

[pʲi̝tʲ] (help·info) ('to drink'). When preceded and followed by coronal or dorsal consonants, [ɨ] is fronted to [ɨ̟].[8] After a cluster of a labial and /ɫ/, [ɨ] is retracted, as in плыть ![]() [pɫɨ̠tʲ] ('to float'); it is also slightly diphthongized to [ɯ̟ɨ̟].[8]

[pɫɨ̠tʲ] ('to float'); it is also slightly diphthongized to [ɯ̟ɨ̟].[8]

In native words, /e/ only follows unpaired (i.e. the retroflexes and /ts/) and soft consonants. After soft consonants (but not before), it is a mid vowel [ɛ̝] (hereafter represented without the diacritic for simplicity), while a following soft consonant raises it to close-mid [e]. Another allophone, an open-mid [ɛ] occurs word-initially and between hard consonants.[9] Preceding hard consonants retract /e/ to [ɛ̠] and [e̠][10] so that жест ('gesture') and цель ('target') are pronounced ![]() [ʐɛ̠st] and

[ʐɛ̠st] and ![]() [tse̠lʲ] respectively.

[tse̠lʲ] respectively.

In words borrowed from other languages, /e/ rarely follows soft consonants; this foreign pronunciation often persists in Russian for many years until the word is more fully adopted into Russian.[11] For instance, шофёр (from French chauffeur) was pronounced ![]() [ʂoˈfɛr] in the early twentieth century,[12] but is now pronounced

[ʂoˈfɛr] in the early twentieth century,[12] but is now pronounced ![]() [ʂʌˈfʲɵr]. On the other hand, the pronunciations of words such as отель

[ʂʌˈfʲɵr]. On the other hand, the pronunciations of words such as отель ![]() [ʌˈtelʲ] ('hotel') retain the hard consonants despite a long presence in the language.

[ʌˈtelʲ] ('hotel') retain the hard consonants despite a long presence in the language.

Back vowels

Between soft consonants, /a/ becomes [æ],[13] as in пять ![]() [pʲætʲ] (help·info) ('five'). When not following a soft consonant, /a/ is retracted to [ɑ̟] before /l/ as in палка

[pʲætʲ] (help·info) ('five'). When not following a soft consonant, /a/ is retracted to [ɑ̟] before /l/ as in палка ![]() [ˈpɑ̟ɫkə] ('stick').[13]

[ˈpɑ̟ɫkə] ('stick').[13]

For most speakers, /o/ is a mid vowel [o̞], but it can be more open [ɔ] for some speakers.[14] Following a soft consonant, /o/ is centralized and raised to [ɵ] as in тётя ![]() [ˈtʲɵtʲə] ('aunt').[15][16]

[ˈtʲɵtʲə] ('aunt').[15][16]

As with the other back vowels, /u/ is centralized to [ʉ] between soft consonants, as in чуть ![]() [tɕʉtʲ] ('narrowly'). When unstressed, /u/ becomes near-close; central [ʉ̞] between soft consonants, centralized back [ʊ] in other positions.[17]

[tɕʉtʲ] ('narrowly'). When unstressed, /u/ becomes near-close; central [ʉ̞] between soft consonants, centralized back [ʊ] in other positions.[17]

Unstressed vowels

Russian unstressed vowels have lower intensity and lower energy. They are typically shorter than stressed vowels, and /a e o i/ in most unstressed positions tend to undergo mergers for most dialects:[18]

- /o/ has merged with /a/: for instance, валы́ 'bulwarks' and волы́ 'oxen' are both pronounced /vaˈɫi/, phonetically

[vʌˈɫɨ].

[vʌˈɫɨ]. - /e/ has merged with /i/: for instance, лиса́ (lisá) 'fox' and леса́ 'forests' are both pronounced /lʲiˈsa/, phonetically

[lʲɪˈsa].[example needed]

[lʲɪˈsa].[example needed] - /a/ and /o/[19] have merged with /i/ after soft consonants: for instance, ме́сяц (mésjats) 'month' is pronounced /ˈmʲesʲits/, phonetically

[ˈmʲesʲɪts].

[ˈmʲesʲɪts].

The merger of unstressed /e/ and /i/ in particular is less universal in the pretonic (pre-accented) position than that of unstressed /o/ and /a/. For example, speakers of some rural dialects as well as the "Old Petersburgian" pronunciation may have the latter but not the former merger, distinguishing between лиса́ [lʲɪˈsa] and леса́ [lʲɘˈsa], but not between валы́ and волы́ (both [vʌˈɫɨ]). The distinction in some loanwords between unstressed /e/ and /i/, or /o/ and /a/ is codified in some pronunciation dictionaries (Avanesov (1985:663), Zarva (1993:15)), for example, фо́рте [ˈfortɛ] and ве́то [ˈvʲeto].

is sometimes preserved word-finally, for example in second-person plural or formal verb forms with the ending -те, such as де́лаете ("you do") /ˈdʲeɫajitʲe/ (phonetically [ˈdʲeɫə(j)ɪtʲe]).|date=July 2017}}

As a result, in most unstressed positions, only three vowel phonemes are distinguished after hard consonants (/u/, /a ~ o/, and /e ~ i/), and only two after soft consonants (/u/ and /a ~ o ~ e ~ i/). For the most part, Russian orthography (as opposed to that of closely related Belarusian) does not reflect vowel reduction. This can be seen in Russian не́бо (nébo) as against Belarusian не́ба (néba) "sky", both of which can be phonemically analyzed as /ˈnʲeba/.

Vowel mergers

In terms of actual pronunciation, there are at least two different levels of vowel reduction: vowels are less reduced when a syllable immediately precedes the stressed one, and more reduced in other positions.[20] This is particularly visible in the realization of unstressed /o/ and /a/, where a less-reduced allophone [ʌ] appears alongside a more-reduced allophone [ə].

The pronunciation of unstressed /o ~ a/ is as follows:

- [ʌ] (sometimes transcribed as [ɐ]; the latter is phonetically correct for the standard Moscow pronunciation, whereas the former is phonetically correct for the standard Saint Petersburg pronunciation;[21] this article uses only the symbol [ʌ]) appears in the following positions:

- In the syllable immediately before the stress, when a hard consonant precedes:[22] паро́м

[pʌˈrom] (help·info) ('ferry'), трава́

[pʌˈrom] (help·info) ('ferry'), трава́  [trʌˈva] ('grass').

[trʌˈva] ('grass'). - In absolute word-initial position.[23]

- In hiatus, when the vowel occurs twice without a consonant between; this is written ⟨aa⟩, ⟨ao⟩, ⟨oa⟩, or ⟨oo⟩:[23] сообража́ть

[sʌʌbrʌˈʐatʲ] ('to use common sense, to reason').

[sʌʌbrʌˈʐatʲ] ('to use common sense, to reason').

- In the syllable immediately before the stress, when a hard consonant precedes:[22] паро́м

- [ə] appears elsewhere, when a hard consonant precedes: о́блако

[ˈobɫəkə] ('cloud').

[ˈobɫəkə] ('cloud'). - When a soft consonant or /j/ precedes, both /o/ and /a/ merge with /i/ and are pronounced as [ɪ]. Example: язы́к

[jɪˈzɨk] 'tongue'). /o/ is written as ⟨e⟩ in these positions.

[jɪˈzɨk] 'tongue'). /o/ is written as ⟨e⟩ in these positions.

- This merger also tends to occur after formerly soft consonants now pronounced hard (/ʐ/, /ʂ/, /ts/),[24] where the pronunciation [ɨ̞][25] occurs. This always occurs when the spelling uses the soft vowel variants, e.g. жена́

[ʐɨ̞ˈna] (help·info) ('wife'), with underlying /o/. However, it also occurs in a few word roots where the spelling writes a hard /a/.[26][27] Examples:

[ʐɨ̞ˈna] (help·info) ('wife'), with underlying /o/. However, it also occurs in a few word roots where the spelling writes a hard /a/.[26][27] Examples:

- жал- 'regret': e.g. жале́ть

[ʐɨˈlʲetʲ] ('to regret'), к сожале́нию

[ʐɨˈlʲetʲ] ('to regret'), к сожале́нию  [ksəʐɨˈlʲenʲɪjʉ] ('unfortunately').

[ksəʐɨˈlʲenʲɪjʉ] ('unfortunately'). - ло́шадь 'horse', e.g. лошаде́й,

[ɫəʂɨˈdʲej] (pl. gen. and acc.).

[ɫəʂɨˈdʲej] (pl. gen. and acc.). - -дцать- in numbers: e.g. двадцати́

[dvətsɨˈtʲi] ('twenty [gen., dat., prep.]'), тридцатью́

[dvətsɨˈtʲi] ('twenty [gen., dat., prep.]'), тридцатью́  [trʲɪtsɨˈtʲjʉ] ('thirty [instr.]').

[trʲɪtsɨˈtʲjʉ] ('thirty [instr.]'). - ржано́й

[rʐɨˈnɵj] ('rye [adj. m. nom.]').

[rʐɨˈnɵj] ('rye [adj. m. nom.]'). - жасми́н

[ʐɨˈsmʲin] ('jasmine').

[ʐɨˈsmʲin] ('jasmine').

- жал- 'regret': e.g. жале́ть

- This merger also tends to occur after formerly soft consonants now pronounced hard (/ʐ/, /ʂ/, /ts/),[24] where the pronunciation [ɨ̞][25] occurs. This always occurs when the spelling uses the soft vowel variants, e.g. жена́

- These processes occur even across word boundaries as in под морем [pʌd‿ˈmɵrʲɪm] ('under the sea').

The pronunciation of unstressed /e ~ i/ is [ɪ] after soft consonants and /j/, and word-initially (эта́п ![]() [ɪˈtap] ('stage')), but [ɨ̞] after hard consonants (дыша́ть

[ɪˈtap] ('stage')), but [ɨ̞] after hard consonants (дыша́ть ![]() [dɨ̞ˈʂatʲ] ('to breathe')).

[dɨ̞ˈʂatʲ] ('to breathe')).

There are a number of exceptions to the above vowel-reduction rules:

- Vowels may not merge in foreign borrowings,[28][29][30] particularly with unusual or recently borrowed words such as ра́дио,

[ˈradʲɪo] (help·info) 'radio'. In such words, unstressed /a/ may be pronounced as [ʌ], regardless of context; unstressed /e/ does not merge with /i/ in initial position or after vowels, so word pairs like эмигра́нт and иммигра́нт, or эмити́ровать and имити́ровать, differ in pronunciation. *Across certain word-final inflections, the reductions do not completely apply. For example, after soft or unpaired consonants, unstressed /a/, /e/ and /i/ of a final syllable may be distinguished from each other.[31][32] For example, жи́тели

[ˈradʲɪo] (help·info) 'radio'. In such words, unstressed /a/ may be pronounced as [ʌ], regardless of context; unstressed /e/ does not merge with /i/ in initial position or after vowels, so word pairs like эмигра́нт and иммигра́нт, or эмити́ровать and имити́ровать, differ in pronunciation. *Across certain word-final inflections, the reductions do not completely apply. For example, after soft or unpaired consonants, unstressed /a/, /e/ and /i/ of a final syllable may be distinguished from each other.[31][32] For example, жи́тели  [ˈʐɨtʲɪlʲɪ] ('residents') contrasts with both (о) жи́теле

[ˈʐɨtʲɪlʲɪ] ('residents') contrasts with both (о) жи́теле  [(ʌ) ˈʐɨtʲɪlʲɪ̞] ('[about] a resident') and жи́теля

[(ʌ) ˈʐɨtʲɪlʲɪ̞] ('[about] a resident') and жи́теля  [ˈʐɨtʲɪlʲə] ('of a resident').

[ˈʐɨtʲɪlʲə] ('of a resident'). - If the first vowel of ⟨oa⟩, or ⟨oo⟩ belongs to the conjunctions но ('but') or то ('then'), it is not reduced, even when unstressed.[33]

Other changes

Unstressed /u/ is generally pronounced as a lax (or near-close) [ʊ], e.g. мужчи́на ![]() [mʊˈɕːinə] (help·info) ('man'). Between soft consonants, it becomes centralized to [ʉ̞], as in юти́ться

[mʊˈɕːinə] (help·info) ('man'). Between soft consonants, it becomes centralized to [ʉ̞], as in юти́ться ![]() [jʉ̞ˈtʲitsə] ('to huddle').

[jʉ̞ˈtʲitsə] ('to huddle').

Note a spelling irregularity in /s/ of the reflexive suffix -ся: with a preceding -т- in third-person present and a -ть- in infinitive, it is pronounced as [tsə], i.e. hard instead of with its soft counterpart, since [ts], normally spelled with ⟨ц⟩, is traditionally always hard. In other forms both pronunciations [sə] and [sʲə] alternate for a speaker with some usual form-dependent preferences: in the outdated dialects, reflexive imperative verbs (such as бо́йся, lit. "be afraid yourself") may be pronounced with [sə] instead of modern (and phonetically consistent) [sʲə].[34]

In weakly stressed positions, vowels may become voiceless between two voiceless consonants: вы́ставка ![]() [ˈvɨstə̥fkə] ('exhibition'), потому́ что

[ˈvɨstə̥fkə] ('exhibition'), потому́ что ![]() [pə̥tʌˈmu ʂtə] ('because'). This may also happen in cases where only the following consonant is voiceless: че́реп

[pə̥tʌˈmu ʂtə] ('because'). This may also happen in cases where only the following consonant is voiceless: че́реп ![]() [ˈtɕerʲɪ̥p] ('skull').

[ˈtɕerʲɪ̥p] ('skull').

Phonemic analysis

Because of mergers of different phonemes in unstressed position, the assignment of a particular phone to a phoneme requires phonological analysis. There have been different approaches to this problem:[35]

- The Saint Petersburg phonology school assigns allophones to particular phonemes. For example, any [ʌ] is considered as a realization of /a/.

- The Moscow phonology school uses an analysis with morphophonemes (морфоне́мы, singular морфоне́ма). It treats a given unstressed allophone as belonging to a particular morphophoneme depending on morphological alternations, or on etymology (which is often reflected in the spelling). For example, [ʌ] is analyzed as either |a| or |o|. To make a determination, one must seek out instances where an unstressed morpheme containing [ʌ] in one word is stressed in another word. Thus, because the word валы́ [vʌˈɫɨ] ('shafts') shows an alternation with вал [vaɫ] ('shaft'), this instance of [ʌ] belongs to the morphophoneme |a|. Meanwhile, волы́ [vʌˈɫɨ] ('oxen') alternates with вол [voɫ] ('ox'), showing that this instance of [ʌ] belongs to the morphophoneme |o|. If there are no alternations between stressed and unstressed syllables for a particular morpheme, then the assignment is based on etymology.

- Some linguists[36] prefer to avoid making the decision. Their terminology includes strong vowel phonemes (the five) for stressed vowels plus several weak phonemes for unstressed vowels: thus, [ɪ] represents the weak phoneme /ɪ/, which contrasts with other weak phonemes, but not with strong ones.

Diphthongs

Russian diphthongs all end in a non-syllabic [i̯], an allophone of /j/ and the only semivowel in Russian. In all contexts other than after a vowel, /j/ is considered an approximant consonant. Phonological descriptions of /j/ may also classify it as a consonant even in the coda. In such descriptions, Russian has no diphthongs.

The first part of diphthongs are subject to the same allophony as their constituent vowels. Examples of words with diphthongs: яйцо́ ![]() [jɪjˈtso] (help·info) ('egg'), ей

[jɪjˈtso] (help·info) ('egg'), ей ![]() [jej] ('her' dat.), де́йственный

[jej] ('her' dat.), де́йственный ![]() [ˈdʲejstvʲɪnnɨj] ('effective'). /ij/, written ⟨-ий⟩ or ⟨-ый⟩, is a common inflexional affix of adjectives, participles, and nouns, where it is often unstressed; at normal conversational speed, such unstressed endings may be monophthongized to [ɪ̟].[37]

[ˈdʲejstvʲɪnnɨj] ('effective'). /ij/, written ⟨-ий⟩ or ⟨-ый⟩, is a common inflexional affix of adjectives, participles, and nouns, where it is often unstressed; at normal conversational speed, such unstressed endings may be monophthongized to [ɪ̟].[37]

Consonants

⟨ʲ⟩ denotes palatalization, meaning the center of the tongue is raised during and after the articulation of the consonant. Phonemes that have at different times been disputed are enclosed in parentheses.

| Labial | Dental, Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hard | soft | hard | soft | hard | soft | hard | soft | ||

| Nasal | m | mʲ | n | nʲ | |||||

| Stop | voiceless | p | pʲ | t | tʲ | k | (kʲ) | ||

| voiced | b | bʲ | d | dʲ | ɡ | (ɡʲ) | |||

| Affricate | ts | (tsʲ) | tɕ | ||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | fʲ | s | sʲ | ʂ | ɕː | x | (xʲ) |

| voiced | v | vʲ | z | zʲ | ʐ | (ʑː) | (ɣ) | ||

| Approximant | ɫ | lʲ | j | ||||||

| Trill | rʲ | r | |||||||

- Notes

- Most consonant phonemes come in hard–soft pairs, except for always-hard /ts, ʂ, ʐ/ and always-soft /tɕ, ɕː, j/ and formerly /ʑː/. There is a marked tendency of Russian hard consonants to be velarized, though this is a subject of some academic dispute.[38][39] Velarization is clearest before the front vowels /e/ and /i/.[40][41]

- /ʐ/ and /ʂ/ are always hard in native words (even if spelling contains a "softening" letter after them, as in жена, шёлк, жить, мышь, жюри, парашют etc.), and for most speakers also in foreign proper names, mostly of French or Lithuanian origin (e.g. Гёльджюк [ˈɡʲɵlʲdʐʊk], Жён Африк [ˈʐon ʌˈfrʲik], Жюль Верн [ˈʐulʲ ˈvɛrn], Герхард Шюрер [ˈɡʲerxərt ˈʂurɨr], Шяуляй, Шяшувис)[42] and tend to be always at least slightly labialized, including when followed by unrounded vowels.[43] Long phonemes /ʑː/ and /ɕː/ do not pattern in the same ways that other hard–soft pairs do. ** /ts/ is generally listed among the always-hard consonants; however, certain foreign proper names, including those of Ukrainian, Polish, Lithuanian, or German origin (e.g. Цюрупа, Пацюк, Цявловский, Цюрих), as well as loanwords (e.g., хуацяо, from Chinese) contain a soft [tsʲ].[44] The phonemicity of a soft /tsʲ/ is supported by neologisms that come from native word-building processes (e.g. фрицёнок, шпицята). However, according to Yanushevskaya & Bunčić (2015), /ts/ really is always hard, and realizing it as palatalized [tsʲ] is considered "emphatically non-standard", and occurs only in some regional accents.[43]

- /tɕ/ and /j/ are always soft.

- /ɕː/ is also always soft.[43] A formerly common pronunciation of /ɕ/+/tɕ/[45] indicates the sound may be two underlying phonemes: /ʂ/ and /tɕ/, thus /ɕː/ can be considered as a marginal phoneme. In today's most widespread pronunciation, [ɕtɕ] appears (instead of [ɕː]) for orthographical -зч-/-сч- where ч- starts the root of a word, and -з/-с belongs to a preposition or a "clearly distinguishable" prefix (e.g. без часо́в

[bʲɪɕtɕɪˈsof] (help·info), 'without a clock'; расчерти́ть

[bʲɪɕtɕɪˈsof] (help·info), 'without a clock'; расчерти́ть  [rəɕtɕɪrˈtʲitʲ], 'to rule'); in all other cases /ɕː/ is used (щётка

[rəɕtɕɪrˈtʲitʲ], 'to rule'); in all other cases /ɕː/ is used (щётка  [ˈɕːɵtkə], гру́зчик

[ˈɕːɵtkə], гру́зчик  [ˈɡruɕːɪk], перепи́счик [pʲɪrʲɪˈpʲiɕːɪk], сча́стье

[ˈɡruɕːɪk], перепи́счик [pʲɪrʲɪˈpʲiɕːɪk], сча́стье  [ˈɕːæsʲtʲjə], мужчи́на

[ˈɕːæsʲtʲjə], мужчи́на  [mʊˈɕːinə], исщипа́ть [ɪɕːɪˈpatʲ], расщепи́ть [rəɕːɪˈpʲitʲ] etc.)

[mʊˈɕːinə], исщипа́ть [ɪɕːɪˈpatʲ], расщепи́ть [rəɕːɪˈpʲitʲ] etc.) - The marginal[46] phoneme /ʑː/ is used only by speakers of the conservative Moscow accent, and is somewhat obsolete. The corresponding modern pronunciation is hard [ʐː].[47] This sound may derive from an underlying /zʐ/ or /sʐ/: заезжа́ть [zə(ɪ̯)ɪˈʑːætʲ], modern

[zə(ɪ̯)ɪˈʐːatʲ]. In modern accent it can only be formed by assimilative voicing of [ɕː] (including across words): вещдо́к [vʲɪʑːˈdok]. For more information, see alveolo-palatal consonant and retroflex consonant.

[zə(ɪ̯)ɪˈʐːatʲ]. In modern accent it can only be formed by assimilative voicing of [ɕː] (including across words): вещдо́к [vʲɪʑːˈdok]. For more information, see alveolo-palatal consonant and retroflex consonant.

- /ʂ/ and /ʐ/ are somewhat concave apical postalveolar.[48] They may be described as retroflex, e.g. by (Hamann 2004), but this is to indicate that they are not laminal nor palatalized; not to say that they are subapical.[49]

- Hard /t, d, n/ are laminal denti-alveolar [t̪, d̪, n̪]; unlike in many other languages, /n/ does not become velar [ŋ] before velar consonants.[50]

- Hard /ɫ/ has been variously described as pharyngealized apical alveolar [l̺ˤ][51] and velarized laminal denti-alveolar [l̪ˠ].[39][52][53]

- Hard /r/ is postalveolar, typically a trill [r̠].[54]

- Soft /rʲ/ is an apical dental trill [r̪ʲ], usually with only a single contact.[54]

- Soft /tʲ, dʲ, nʲ/ are laminal alveolar [t̻ʲsʲ, d̻ʲzʲ, n̻ʲ]. In the case of the first two, the tongue is raised just enough to produce slight frication as indicated in the transcription.[55]

- Soft /lʲ/ is either laminal alveolar [l̻ʲ] or laminal denti-alveolar [l̪ʲ].[51][56]

- /ts, s, sʲ, z, zʲ/ are dental [t̪s̪, s̪, s̪ʲ, z̪, z̪ʲ],[57] i.e. dentalized laminal alveolar. They are pronounced with the blade of the tongue very close to the upper front teeth, with the tip of the tongue resting behind the lower front teeth.

- The voiced /v, vʲ/ are often realized with weak friction [v̞, v̞ʲ] or even as approximants [ʋ, ʋʲ], particularly in spontaneous speech.[43]

- A marginal phoneme /ɣ/ occurs instead of /ɡ/ in certain interjections: ага́, ого́, угу́, эге, о-го-го́, э-ге-ге, гоп. (Thus, there exists a minimal pair of homographs: ага́

[ʌˈɣa] (help·info) 'aha!' vs ага́

[ʌˈɣa] (help·info) 'aha!' vs ага́  [ʌˈɡa] 'agha'). The same sound [ɣ] can be found in бухга́лтер (spelled ⟨хг⟩, though in цейхга́уз, ⟨хг⟩ is [x]), optionally in га́битус and in a few other loanwords. Also optionally (and less frequently than a century ago) [ɣ] can be used instead of [ɡ] in certain religious words (a phenomenon influenced by Church Slavonic pronunciation): Бо́га [ˈboɣə], Бо́гу [ˈboɣʊ]... (declension forms of Бог [ˈbox] 'God'), Госпо́дь [ɣʌˈspɵtʲ] 'Lord' (especially in the exclamation Го́споди! [ˈɣospədʲɪ] 'Oh Lord!'), благо́й [bɫʌˈɣɵj] 'good'.

[ʌˈɡa] 'agha'). The same sound [ɣ] can be found in бухга́лтер (spelled ⟨хг⟩, though in цейхга́уз, ⟨хг⟩ is [x]), optionally in га́битус and in a few other loanwords. Also optionally (and less frequently than a century ago) [ɣ] can be used instead of [ɡ] in certain religious words (a phenomenon influenced by Church Slavonic pronunciation): Бо́га [ˈboɣə], Бо́гу [ˈboɣʊ]... (declension forms of Бог [ˈbox] 'God'), Госпо́дь [ɣʌˈspɵtʲ] 'Lord' (especially in the exclamation Го́споди! [ˈɣospədʲɪ] 'Oh Lord!'), благо́й [bɫʌˈɣɵj] 'good'. - Some linguists (like I. G. Dobrodomov and his school) postulate the existence of a phonemic glottal stop /ʔ/. This marginal phoneme can be found, for example, in the word не́-а

[ˈnʲeʔə] (help·info). Claimed minimal pairs for this phoneme include су́женный

[ˈnʲeʔə] (help·info). Claimed minimal pairs for this phoneme include су́женный  [ˈsʔuʐɨnɨj] 'narrowed' (a participle from су́зить 'to narrow', with prefix с- and root -уз-, cf. у́зкий 'narrow') vs су́женый

[ˈsʔuʐɨnɨj] 'narrowed' (a participle from су́зить 'to narrow', with prefix с- and root -уз-, cf. у́зкий 'narrow') vs су́женый  [ˈsuʐɨnɨj] 'betrothed' (originally a participle from суди́ть 'to judge', now an adjective; the root is суд 'court') and с А́ней

[ˈsuʐɨnɨj] 'betrothed' (originally a participle from суди́ть 'to judge', now an adjective; the root is суд 'court') and с А́ней  [ˈsʔanʲɪj] 'with Ann' vs Са́ней

[ˈsʔanʲɪj] 'with Ann' vs Са́ней  [ˈsanʲɪj] '(by) Alex'.[58][59]

[ˈsanʲɪj] '(by) Alex'.[58][59]

There is some dispute over the phonemicity of soft velar consonants. Typically, the soft–hard distinction is allophonic for velar consonants: they become soft before front vowels, as in коро́ткий ![]() [kʌˈrotkʲɪj] ('short'), unless there is a word boundary, in which case they are hard (e.g. к Ива́ну [k‿ɨˈvanʊ] 'to Ivan').[60] Hard variants occur everywhere else. Exceptions are represented mostly by:

[kʌˈrotkʲɪj] ('short'), unless there is a word boundary, in which case they are hard (e.g. к Ива́ну [k‿ɨˈvanʊ] 'to Ivan').[60] Hard variants occur everywhere else. Exceptions are represented mostly by:

- Loanwords:

- Soft: гёзы, гюрза́, гяу́р, секью́рити, кекс, кяри́з, са́нкхья, хянга́;

- Hard: кок-сагы́з, гэ́льский, акы́н, кэб (кеб), хэ́ппенинг.

- Proper nouns of foreign origin:

- Soft: Алигье́ри, Гёте, Гю́нтер, Гянджа́, Джокьяка́рта, Кёнигсберг, Кюраса́о, Кя́хта, Хью́стон, Хёндэ, Хю́бнер, Пюхяя́рви;

- Hard: Мангышла́к, Гэ́ри, Кызылку́м, Кэмп-Дэ́вид, Архы́з, Хуанхэ́.

The rare native examples are fairly new, as most them were coined in the last century:

- Soft: forms of the verb ткать 'weave' (ткёшь, ткёт etc., and derivatives like соткёшься); догёнок/догята, герцогёнок/герцогята; and adverbial participles of the type берегя, стерегя, стригя, жгя, пекя, секя, ткя (it is disputed whether these are part of the standard language or just informal colloquialisms) ;

- Hard: the name гэ of letter ⟨г⟩, acronyms and derived words (кагебешник, днепрогэсовский), a few interjections (гы, кыш, хэй), some onomatopoeic words (гыгыкать), and colloquial forms of certain patronyms: Олегыч, Маркыч, Аристархыч (where -ыч is a contraction of standard language's patronymical suffix -ович rather than a continuation of ancient -ич).

In the mid-twentieth century, a small number of reductionist approaches made by structuralists[61] put forth that palatalized consonants occur as the result of a phonological processes involving /j/ (or palatalization as a phoneme in itself), so that there were no underlying palatalized consonants.[62] Despite such proposals, linguists have long agreed that the underlying structure of Russian is closer to that of its acoustic properties, namely that soft consonants are separate phonemes in their own right.[63]

Phonological processes

Final devoicing

Voiced consonants (/b/, /bʲ/, /d/, /dʲ/ /ɡ/, /v/, /vʲ/, /z/, /zʲ/, /ʐ/, and /ʑː/) are devoiced word-finally unless the next word begins with a voiced obstruent.[64] г also represents voiceless [x] word-finally in some words, such as бог [ˈbox]. This is related to the use of the marginal (or dialectal) phoneme /ɣ/ in some religious words .

Voicing

Russian features general regressive assimilation of voicing and palatalization.[65] In longer clusters, this means that multiple consonants may be soft despite their underlyingly (and orthographically) being hard.[66] The process of voicing assimilation applies across word-boundaries when there is no pause between words.[67]

Within a morpheme, voicing is not distinctive before obstruents (except for /v/, and /vʲ/ when followed by a vowel or sonorant). The voicing or devoicing is determined by that of the final obstruent in the sequence:[68] просьба ![]() [ˈprɵzʲbə] (help·info) ('request'), водка

[ˈprɵzʲbə] (help·info) ('request'), водка ![]() [ˈvotkə] ('vodka'). In foreign borrowings, this isn't always the case for /f(ʲ)/, as in Адольф Гитлер

[ˈvotkə] ('vodka'). In foreign borrowings, this isn't always the case for /f(ʲ)/, as in Адольф Гитлер ![]() [ʌˈdɵlʲf ˈɡʲitlʲɪr] ('Adolf Hitler') and граф болеет ('the count is ill'). /v/ and /vʲ/ are unusual in that they seem transparent to voicing assimilation; in the syllable onset, both voiced and voiceless consonants may appear before /v(ʲ)/:

[ʌˈdɵlʲf ˈɡʲitlʲɪr] ('Adolf Hitler') and граф болеет ('the count is ill'). /v/ and /vʲ/ are unusual in that they seem transparent to voicing assimilation; in the syllable onset, both voiced and voiceless consonants may appear before /v(ʲ)/:

- тварь

[tvarʲ]) ('the creature')

[tvarʲ]) ('the creature') - два

[dva] ('two')

[dva] ('two') - световой

[s(ʲ)vʲɪtʌˈvɵj] ('of light')

[s(ʲ)vʲɪtʌˈvɵj] ('of light') - звезда

[z(ʲ)vʲɪˈzda] ('star')

[z(ʲ)vʲɪˈzda] ('star')

When /v(ʲ)/ precedes and follows obstruents, the voicing of the cluster is governed by that of the final segment (per the rule above) so that voiceless obstruents that precede /v(ʲ)/ are voiced if /v(ʲ)/ is followed by a voiced obstruent (e.g. к вдове [ɡvdʌˈvʲe] 'to the widow') while a voiceless obstruent will devoice all segments (e.g. без впуска [bʲɪs ˈfpuskə] 'without an admission').[69]

/tɕ/, /ts/, and /x/ have voiced allophones ([dʑ], [dz] and [ɣ]) before voiced obstruents,[64][70] as in дочь бы ![]() [ˈdɵdʑ bɨ][71] ('a daughter would') and плацдарм

[ˈdɵdʑ bɨ][71] ('a daughter would') and плацдарм ![]() [pɫʌdzˈdarm] ('bridge-head').

[pɫʌdzˈdarm] ('bridge-head').

Other than /mʲ/ and /nʲ/, nasals and liquids devoice between voiceless consonants or a voiceless consonant and a pause: контрфорс ![]() [ˌkontr̥ˈfors]) ('buttress').[72]

[ˌkontr̥ˈfors]) ('buttress').[72]

Palatalization

Before /j/, paired consonants (that is, those that come in a hard-soft pair) are normally soft as in пью ![]() [pʲjʉ] 'I drink' and бью

[pʲjʉ] 'I drink' and бью ![]() [bʲjʉ] 'I hit'. However, the last consonant of prefixes and parts of compound words generally remains hard in the standard language: отъезд

[bʲjʉ] 'I hit'. However, the last consonant of prefixes and parts of compound words generally remains hard in the standard language: отъезд ![]() [ʌˈtjest] 'departure', Минюст

[ʌˈtjest] 'departure', Минюст ![]() [ˌmʲiˈnjʉst] 'Min[istry of] Just[ice]'; when the prefix ends in /s/ or /z/ there may be an optional softening: съездить

[ˌmʲiˈnjʉst] 'Min[istry of] Just[ice]'; when the prefix ends in /s/ or /z/ there may be an optional softening: съездить ![]() [ˈs(ʲ)jezʲdʲɪtʲ] ('to travel').

[ˈs(ʲ)jezʲdʲɪtʲ] ('to travel').

Paired consonants preceding /e/ are also soft; although there are exceptions from loanwords, alternations across morpheme boundaries are the norm.[73] The following examples[74] show some of the morphological alternations between a hard consonant and its soft counterpart:

| hard | soft |

|---|---|

Velar consonants are soft when preceding /i/, and never occur before [ɨ] within a word.[75]

Before hard dental consonants, /r/, labial and dental consonants are hard: орла ![]() [ʌrˈɫa] ('eagle' gen. sg).

[ʌrˈɫa] ('eagle' gen. sg).

Assimilative palatalization

Paired consonants preceding another consonant often inherit softness from it. This phenomenon in literary language has complicated and evolving rules with many exceptions, depending on what these consonants are, in what morphemic position they meet and to what style of speech the word belongs. In old Moscow pronunciation, softening was more widespread and regular; nowadays some cases that were once normative have become low colloquial or archaic. In fact, consonants can be softened to very different extent, become semi-hard or semi-soft.

The more similar the consonants are, the more they tend to soften each other. Also, some consonants tend to be softened less, such as labials and /r/.

Softening is stronger inside the word root and between root and suffix; it is weaker between prefix and root and weak or absent between a preposition and the word following.[76]

- Before soft dental consonants, /lʲ/ and often soft labial consonants, dental consonants (other than /ts/) are soft.

- /x/ is assimilated to the palatalization of the following velar consonant: лёгких Audio file "Ru-лёгких.ogg" not found) ('lungs' gen. pl.).

- Palatalization assimilation of labial consonants before labial consonants is in free variation with nonassimilation, such that бомбить ('to bomb') is either [bʌmˈbʲitʲ] or [bʌmʲˈbʲitʲ] depending on the individual speaker.

- When hard /n/ precedes its soft equivalent, it is also soft and likely to form a single long sound (see gemination). This is slightly less common across affix boundaries.

In addition to this, dental fricatives conform to the place of articulation (not just the palatalization) of following postalveolars: с частью Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".) ('with a part'). In careful speech, this does not occur across word boundaries.

Russian has the rare feature of nasals not typically being assimilated in place of articulation. Both /n/ and /nʲ/ appear before retroflex consonants: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".) ('money' (scornful)) and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".) ('sanctimonious one' instr.). In the same context, other coronal consonants are always hard.

Consonant clusters

As a Slavic language, Russian has fewer phonotactic restrictions on consonants than many other languages,Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". allowing for clusters that would be difficult for English speakers; this is especially so at the beginning of a syllable, where Russian speakers make no sonority distinctions between fricatives and stops.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". These reduced restrictions begin at the morphological level; outside of two morphemes that contain clusters of four consonants: встрет-/встреч- 'meet' ([ˈfstrʲetʲ/ˈfstrʲetɕ]), and чёрств-/черств- 'stale' ([ˈtɕɵrstv]), native Russian morphemes have a maximum consonant cluster size of three:Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

| Russian | IPA/Audio | Translation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCL | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'to hide' |

| CCC* | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'tree trunk' |

| LCL | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'camel' |

| LCC | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'thick' |

For speakers who pronounce [ɕtɕ] instead of [ɕː], words like Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". ('common') also constitute clusters of this type.

| Russian | IPA/Audio | Translation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CC | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'bone' |

| LC | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'death' |

| CL | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'blind' |

| LL | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'throat' |

| CJ | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'article' |

| LJ | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'zealous' |

If /j/ is considered a consonant in the coda position, then words like Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". ('quince') contain semivowel+consonant clusters.

Affixation also creates consonant clusters. Some prefixes, the best known being вз-/вс- ([vz-]/[fs-]), produce long word-initial clusters when they attach to a morpheme beginning with consonant(s) (e.g. |fs|+ |pɨʂkə| → Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [ˈfspɨʂkə] 'flash'). However, the four-consonant limitation persists in the syllable onset.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

Clusters of three or more consonants are frequently simplified, usually through syncope of one of them,Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". especially in casual pronunciation.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Various cases of relaxed pronunciation in Russian can be seen here.

All word-initial four-consonant clusters begin with [vz] or [fs], followed by a stop (or, in the case of [x], a fricative), and a liquid:

| Russian | IPA/Audio | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| (Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".) Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". (Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".) | [vzbrʲɪˈɫo] | '(he) took it (into his head)' |

| Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'gaze' |

| Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'to perch' |

| Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'to flinch' |

| Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'disheveled' |

| Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'to unseal' |

| Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'splash' |

| Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'to jump up' |

| Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | [ˈfstlʲetʲ] | 'to begin to smolder' |

| Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'to meet' |

| Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | [ˈfsxlʲip] | 'whimper' |

| Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'to snort' |

Because prepositions in Russian act like clitics,Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". the syntactic phrase composed of a preposition (most notably, the three that consist of just a single consonant: к, с, and в) and a following word constitutes a phonological word that acts like a single grammatical word.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". For example, the phrase Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". ('with friends') is pronounced [zdrʊˈzʲjæmʲɪ]. In the syllable coda, suffixes that contain no vowels may increase the final consonant cluster of a syllable (e.g. Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". 'city of Noyabrsk' |noˈjabrʲ|+ |sk| → [nʌˈjæbrʲsk]), theoretically up to seven consonants: *Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [ˈmonstrstf] ('of monsterships').Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". There is usually an audible release between these consecutive consonants at word boundaries, the major exception being clusters of homorganic consonants.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

Consonant cluster simplification in Russian includes degemination, syncope, dissimilation, and weak vowel insertion. For example, /sɕː/ is pronounced [ɕː], as in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". ('cleft'). There are also a few isolated patterns of apparent cluster reduction (as evidenced by the mismatch between pronunciation and orthography) arguably the result of historical simplifications.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". For example, dental stops are dropped between a dental continuant and a dental nasal or lateral: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [ˈlʲesnɨj] 'flattering'.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Other examples include:

| /vstv/ > [stv] | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'feeling' | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". |

| /ɫnts/ > [nts] | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'sun' | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". |

| /rdts/ > [rts] | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'heart' | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | |

| /rdtɕ/ > [rtɕ] | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'heart' (diminutive) | [sʲɪrˈtɕiʂkə] (not [sʲɪrttɕiʂkə]) | |

| /ndsk/ > [nsk] | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'Scottish' | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". |

| /stsk/ > [sk] | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". | 'Marxist' | [mʌrkˈsʲiskʲɪj] (not [mʌrkˈsʲistskʲɪj]) | Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". |

The simplifications of consonant clusters are done selectively; bookish-style words and proper nouns are typically pronounced with all consonants even if they fit the pattern. For example, the word Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". is pronounced in a simplified manner [ɡʌˈɫankə] for the meaning of 'Dutch oven' (a popular type of oven in Russia) and in a full form [ɡʌˈɫantkə] for 'Dutch woman' (a more exotic meaning).

In certain cases, this syncope produces homophones, e.g. Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". ('bony') and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". ('rigid'), both are pronounced Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24"..

Another method of dealing with consonant clusters is inserting an epenthetic vowel (both in spelling and in pronunciation), ⟨о⟩, after most prepositions and prefixes that normally end in a consonant. This includes both historically motivated usage and cases of its modern extrapolations. There are no strict limits when the epenthetic ⟨о⟩ is obligatory, optional, or prohibited. One of the most typical cases of the epenthetic ⟨о⟩ is between a morpheme-final consonant and a cluster starting with the same or similar consonant (e.g. Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". 'from Wednesday' |s|+ |srʲɪˈdɨ| → [səsrʲɪˈdɨ], not *с среды; Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". 'I'll scrub' |ot|+ |ˈtru| → [ʌtʌˈtru], not *оттру).

Supplementary notes

There are numerous ways in which Russian spelling does not match pronunciation. The historical transformation of /ɡ/ into /v/ in genitive case endings and the word for 'him' is not reflected in the modern Russian orthography: the pronoun Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [jɪˈvo] 'his/him', and the adjectival declension suffixes -ого and -его. Orthographic г represents /x/ in a handful of word roots: легк-/лёгк-/легч- 'easy' and мягк-/мягч- 'soft'. There are a handful of words in which consonants which have long since ceased to be pronounced even in careful pronunciation are still spelled, e.g., the 'l' in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [ˈsontsɨ] ('sun').

/n/ and /nʲ/ are the only consonants that can be geminated within morpheme boundaries. Such gemination does not occur in loanwords.

Between any vowel and /i/ (excluding instances across affix boundaries but including unstressed vowels that have merged with /i/), /j/ may be dropped: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [ˈa.ɪst] ('stork') and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [ˈdʲeɫəɪt] ('does').Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". (Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". cites Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". and other instances of intervening prefix and preposition boundaries as exceptions to this tendency.)

Stress in Russian may fall on any syllable and words can contrast based just on stress (e.g. Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [ˈmukə] 'ordeal, pain, anguish' vs. [mʊˈka] 'flour, meal, farina'); stress shifts can even occur within an inflexional paradigm: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [ˈdomə] ('house' gen. sg.) vs Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [dʌˈma] ('houses'). The place of the stress in a word is determined by the interplay between the morphemes it contains, as some morphemes have underlying stress, while others do not. However, other than some compound words, such as Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [mʌˌrozəʊˈstɵjtɕɪvɨj] ('frost-resistant') only one syllable is stressed in a word.Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

/i/ velarizes hard consonants: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". ('you' sing.). /o/ and /u/ velarize and labialize hard consonants and labialize soft consonants: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". ('side'), Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". ('(he) carried').Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

Between a hard consonant and /o/, a slight [w] offglide occurs, most noticeably after labial, labio-dental and velar consonants (e.g. Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24"., 'was soaking' [mˠwok]).Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". Similarly, a weak palatal offglide may occur between certain soft consonants and back vowels (e.g. Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". 'thigh' [ˈlʲjæʂkə]).Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

See also

- Help:IPA/Russian

- Russian alphabet

- Russian orthography

- Reforms of Russian orthography

- History of the Russian language

- List of Russian language topics

- Index of phonetics articles

References

- ↑ See, for example, Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".; Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".; Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".. The traditional name of ⟨ы⟩, Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". [jɪˈrɨ] yery; since 1961 this name has been replaced from the Russian school practice (compare the 7th and 8th editions of the standard textbook of Russian for 5th and 6th grades: Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24"., and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24"..

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Chew 2003, p. 61.

- ↑ Chew 2003, p. 62.

- ↑ See, for example, Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".; Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".; Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".; Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Thus, /ɨ/ is pronounced something like [ɤ̯ɪ], with the first part sounding as an on-glide Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, pp. 37-38.

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, p. 31.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Jones & Ward 1969, p. 33.

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, pp. 41-44.

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, p. 193.

- ↑ Halle 1959, p. 63.

- ↑ As in Igor Severyanin's poem, Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". . . .

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Jones & Ward 1969, p. 50.

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, p. 56.

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, p. 62.

- ↑ Halle 1959, p. 166.

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, pp. 67-69.

- ↑ Crosswhite 2000, p. 112.

- ↑ /o/ has merged with /i/ if words such as тепло́ /tʲiˈpɫo/ 'heat' are analyzed as having the same morphophonemes as related words such as тёплый /ˈtʲopɫij/ 'warm', meaning that both of them have the stem |tʲopl-|. Alternatively, they can be analyzed as having two different morphophonemes, |o| and |e|: |tʲopɫ-| vs. |tʲepɫ-|. In that analysis, |o| does not occur in тепло́, so |o| does not merge with |i|. Historically, the |o| developed from |e|: see History of the Russian language § The yo vowel.

- ↑ Avanesov 1975, p. 105-106.

- ↑ Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Padgett & Tabain 2005, p. 16.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Jones & Ward 1969, p. 51.

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, p. 194.

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, p. 38.

- ↑ Avanesov 1985, p. 663.

- ↑ Zarva 1993, p. 13.

- ↑ Avanesov 1985, p. 663-666.

- ↑ Zarva 1993, p. 12-17.

- ↑ Halle 1959.

- ↑ Avanesov 1975, p. 121-125.

- ↑ Avanesov 1985, p. 666.

- ↑ Zarva 1983, p. 16.

- ↑ Wade, Terence Leslie Brian (2010). A Comprehensive Russian Grammar (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4051-3639-6.

- ↑ Avanesov 1975, p. 37-40.

- ↑ e.g. Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, p. 37.

- ↑ Padgett 2001, p. 7.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".: "Note that though Russian has traditionally been described as having all consonants either palatalized or velarized, recent data suggests that the velarized gesture is only used with laterals giving a phonemic contrast between /lʲ/ and /ɫ/ (...)."

- ↑ Padgett 2003b, p. 319.

- ↑ Because of the acoustic properties of [u] and [i] that make velarization more noticeable before front vowels and palatalization before back vowels Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". argues that the contrast before /i/ is between velarized and plain consonants rather than plain and palatalized.

- ↑ See dictionaries of Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24"..

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 43.3 Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ The dictionary Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". explicitly says that the nonpalatalized pronunciation /ts/ is an error in such cases.

- ↑ See Avanesov's pronunciation guide in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Padgett 2003a, p. 42.

- ↑ Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Hamann 2004, p. 64.

- ↑ Hamann 2004, p. 56, "Summing up the articulatory criteria for retroflex fricatives, they are all articulated behind the alveolar ridge, show a sub-lingual cavity, are articulated with the tongue tip (though this is not always discernible in the x-ray tracings), and with a retracted and flat tongue body."

- ↑ Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24"., cited in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".; cited in Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".. This source mentions only the laminal alveolar realization.

- ↑ Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Dobrodomov & Izmest'eva 2002.

- ↑ Dobrodomov & Izmest'eva 2009.

- ↑ Padgett 2003a, pp. 44, 47.

- ↑ Stankiewicz 1962, p. 131.

- ↑ see Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". for two examples.

- ↑ See Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". and Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". for a criticism of Bidwell's approach specifically and the reductionist approach generally.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Halle 1959, p. 22.

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, p. 156.

- ↑ Lightner 1972, p. 377.

- ↑ Lightner 1972, p. 73.

- ↑ Halle 1959, p. 31.

- ↑ Lightner 1972, p. 75.

- ↑ Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

- ↑ Lightner 1972, p. 82.

- ↑ Jones & Ward 1969, p. 190.

- ↑ Padgett 2003a, p. 43.

- ↑ Lightner 1972, pp. 9–11, 12–13.

- ↑ Padgett 2003a, p. 39.

- ↑ Аванесов, Р. И. (1984). Русское Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24". произношение. М.: Просвещение. pp. 145–167.

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

Bibliography

- Ageenko, F.L.; Zarva, M.V., eds. (1993) (in Russian), Moscow: Russkij Yazyk, pp. 9–31, ISBN 5-200-01127-2

- Ashby, Patricia (2011), Understanding Phonetics, Understanding Language series, Routledge, ISBN 978-0340928271

- Avanesov, R.I. (1975) [1956] (in Russian), Lepizig: Zentralantiquariat der DDR

- Avanesov, R.I. (1985), "Сведения о произношении и ударении [Information on pronunciation and stress].", in Borunova, C.N.; Vorontsova, V.L.; Yes'kova, N.A. (in Russian) (2nd ed.), pp. 659–684

- Barkhudarov, S. G; Protchenko, I. F; Skvortsova, L. I, eds (1987) (in Russian) (11 ed.).

- Barkhudarov, S. G; Kryuchkov, S.E. (1960), Учебник русского языка, ч. 1. Фонетика и морфология. Для 5-го и 6-го классов средней школы (7th ed.), Moscow

- Barkhudarov, S. G; Kryuchkov, S.E. (1961), Учебник русского языка, ч. 1. Фонетика и морфология. Для 5-го и 6-го классов средней школы (8th ed.), Moscow

- Bickel, Balthasar; Nichols, Johanna (2007), "Inflectional morphology", in Shopen, Timothy, Language Typology and Syntactic Description. Vol. III: Grammatical categories and the lexicon. (2nd ed.), London: Routledge, pp. Chapter 3

- Bidwell, Charles (1962), "An Alternate Phonemic Analysis of Russian", The Slavic and East European Journal (American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages) 6 (2): 125–129, doi:10.2307/3086096

- Borunova, C.N.; Vorontsova, V.L.; Yes'kova, N.A., eds. (1983) (in Russian) (2nd ed.), pp. 659–684

- Chew, Peter A. (2003), A computational phonology of Russian, Universal Publishers

- Crosswhite, Katherine Margaret (2000), "Vowel Reduction in Russian: A Unified Accountof Standard, Dialectal, and 'Dissimilative' Patterns", University of Rochester Working Papers in the Language Sciences 1 (1): 107–172, archived from the original on 2012-02-06, https://web.archive.org/web/20120206015223/http://www.bcs.rochester.edu/cls/s2000n1/crosswhite.pdf

- Cubberley, Paul (2002), Russian: A Linguistic Introduction, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521796415, https://books.google.com/books?id=yOGzAyN3V88C

- Davidson, Lisa; Roon, Kevin (2008), "Durational correlates for differentiating consonant sequences in Russian", Journal of the International Phonetic Association 38 (2): 137–165, doi:10.1017/S0025100308003447

- Dobrodomov, I. G.; Izmest'eva, I. A. (2002), "Беззаконная фонема /ʔ/ в русском языке.", Проблемы фонетики IV: 36–52

- Dobrodomov, I. G.; Izmest'eva, I. A. (2009), "Роль гортанного смычного согласного в изменении конца слова после падения редуцированных гласных", Известия Самарского научного центра Российской академии наук 11, 4 (4): 1001–1005, http://www.ssc.smr.ru/media/journals/izvestia/2009/2009_4_1001_1006.pdf

- Folejewski, Z (1962), "[An Alternate Phonemic Analysis of Russian]: Editorial comment", The Slavic and East European Journal 6 (2): 129–130, doi:10.2307/3086097

- Halle, Morris (1959), Sound Pattern of Russian, MIT Press

- Hamann, Silke (2004), "Retroflex fricatives in Slavic languages", Journal of the International Phonetic Association 34 (1): 53–67, doi:10.1017/S0025100304001604, archived from the original on 2015-04-14, https://web.archive.org/web/20150414230437/http://www.fon.hum.uva.nl/silke/articles/Hamann%202004.pdf

- Jones, Daniel; Trofimov, M. V. (1923). The pronunciation of Russian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://books.google.com/books?id=Txw9AAAAIAAJ.

- Jones, Daniel; Ward, Dennis (1969), The Phonetics of Russian, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521153003, https://books.google.com/books?id=A9rrVMQ-PxsC

- Koneczna, Halina; Zawadowski, Witold (1956), Obrazy rentgenograficzne głosek rosyjskich, Warsaw: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe

- Krech, Eva Maria; Stock, Eberhard; Hirschfeld, Ursula; Anders, Lutz-Christian (2009), "7.3.13 Russisch", Deutsches Aussprachewörterbuch, Berlin, New York: Walter de Gruyter, ISBN 978-3-11-018202-6

- Kuznetsov, V.V.; Ryzhakov, M.V., eds. (2007), Универсальный справочник школьника, Moscow, ISBN 978-5-373-00858-7

- Ladefoged, Peter; Maddieson, Ian (1996), The Sounds of the World's Languages, Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 0-631-19815-6

- Lightner, Theodore M. (1972), Problems in the Theory of Phonology, I: Russian phonology and Turkish phonology, Edmonton: Linguistic Research, inc

- Mathiassen, Terje (1996), A Short Grammar of Lithuanian, Slavica Publishers, Inc., ISBN 978-0893572679

- Matiychenko, A.S. (1950), Грамматика русского языка. Часть первая. Фонетика, морфология. Учебник для VIII и IX классов нерусских школ. (2nd ed.), Moscow

- Ostapenko, Olesya (2005), "The Optimal L2 Russian Syllable Onset", LSO Working Papers in Linguistics 5: Proceedings of WIGL 2005: 140–151, http://vanhise.lss.wisc.edu/ling/files/ling_old_web/lso/wpl/5.1/LSOWP5.1-11-Ostapenko.pdf

- Ozhegov, S. I. (1953). Словарь русского языка.

- Padgett, Jaye (2001), "Contrast Dispersion and Russian Palatalization", in Hume, Elizabeth; Johnson, Keith, The role of speech perception in phonology, Academic Press, pp. 187–218

- Padgett, Jaye (2003a), "Contrast and Post-Velar Fronting in Russian", Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 21 (1): 39–87, doi:10.1023/A:1021879906505

- Padgett, Jaye (2003b), "The Emergence of Contrastive Palatalization in Russian", in Holt, D. Eric, Optimality Theory and Language Change

- Padgett, Jaye; Tabain, Marija (2005), "Adaptive Dispersion Theory and Phonological Vowel Reduction in Russian", Phonetica 62 (1): 14–54, doi:10.1159/000087223, PMID 16116302, http://people.ucsc.edu/~padgett/locker/vreductpaper.pdf

- Rubach, Jerzy (2000), "Backness switch in Russian", Phonology 17 (1): 39–64, doi:10.1017/s0952675700003821

- Schenker, Alexander M. (2002), "Proto-Slavonic", in Comrie, Bernard; Corbett, Greville. G., The Slavonic Languages, London: Routledge, pp. 60–124, ISBN 0-415-28078-8, https://books.google.com/books?id=uRF9Yiso1OIC&

- Shapiro, Michael (1993), "Russian Non-Distinctive Voicing: A Stocktaking", Russian Linguistics 17 (1): 1–14, doi:10.1007/bf01839412

- Shcherba, Lev V., ed (1950) (in Russian). Грамматика русского языка. Часть I. Фонетика и морфология. Учебник для 5-го и 6-го классов семилетней и средней школы (11th ed.). Moscow.

- Skalozub, Larisa (1963), Palatogrammy i Rentgenogrammy Soglasnyx Fonem Russkogo Literaturnogo Jazyka, Izdatelstvo Kievskogo Universiteta

- Stankiewicz, E. (1962), "[An Alternate Phonemic Analysis of Russian]: Editorial comment", The Slavic and East European Journal (American Association of Teachers of Slavic and East European Languages) 6 (2): 131–132, doi:10.2307/3086098

- Timberlake, Alan (2004), "Sounds", A Reference Grammar of Russian, Cambridge University Press, https://books.google.com/books?id=-VFNWqXxRoMC&pg=PA28

- Toporov, V. N. (1971), "О дистрибутивных структурах конца слова в современном русском языке", in Vinogradov, V. V., Фонетика, фонология, грамматика, Moscow

- Vinogradov, V. V., История Слов:Суть, http://wordhist.narod.ru/sut.html

- Yanushevskaya, Irena; Bunčić, Daniel (2015), "Russian", Journal of the International Phonetic Association 45 (2): 221–228, doi:10.1017/S0025100314000395, https://www.cambridge.org/core/services/aop-cambridge-core/content/view/55589EC639ADEF1764B5ECD0B76970FA/S0025100314000395a.pdf/russian.pdf

- Zarva, M.V. (1993), "Правила произношения", in Ageenko, F.L.; Zarva, M.V. (in Russian), Moscow: Russkij Yazyk, pp. 9–31, ISBN 5-200-01127-2

- Zemsky, A. M; Svetlayev, M. V; Kriuchkov, S. E (1971) (in ru). Русский язык. Часть 1. Лексикология, фонетика и морфология. Учебник для педагогических училищ (11th ed.).

- Zsiga, Elizabeth (2003), "Articulatory Timing in a Second Language: Evidence from Russian and English", Studies in Second Language Acquisition 25: 399–432, doi:10.1017/s0272263103000160

- Zygis, Marzena (2003), "Phonetic and Phonological Aspects of Slavic Sibilant Fricatives", ZAS Papers in Linguistics 3: 175–213, http://www.zas.gwz-berlin.de/fileadmin/material/ZASPiL_Volltexte/zp32/zaspil32-zygis.pdf

Further reading

- Hamilton, William S. (1980), Introduction to Russian Phonology and Word Structure, Slavica Publishers

- Gasanov, A.A.; Babayev, I.A. (2010), Курс лекций по фонетике современного русского языка, archived from the original on 2011-11-11, https://web.archive.org/web/20111111191420/http://bsu-edu.org/ders_vesaitleri/16.pdf

- Hamann, Silke (2002), "Postalveolar Fricatives in Slavic Languages as Retroflexes", in Baauw, S.; Huiskes, M.; Schoorlemmer, M., OTS Yearbook 2002, Utrecht: Utrecht Institute of Linguistics, pp. 105–127, http://www.let.uu.nl/~Silke.Hamann/personal/Hamann2002SlavicRet.pdf, retrieved 2008-02-07

- Press, Ian (1986), Aspects of the phonology of the Slavonic languages: the vowel y and the Consonantal Correlation of Palatalization, Rodopi, ISBN 90-6203-848-4, https://books.google.com/books?id=JYBgH2yEjR0C&printsec=frontcover

- Proctor, Michael (2009), Gestural characterization of a phonological class: the liquids, Yale University

- Rubach, Jerzy (2000), "Backness Switch in Russian", Phonology 17: 39–64, doi:10.1017/S0952675700003821

- Shcherba, Lev Vladimirovich (1912), Russkie glasnye v kachestvennom i kolichestvennom otnoshennii, St. Petersburg: Tipografiia IU.

- Sussex, Roland (1992), "Russian", in Bright, W., International Encyclopedia of Linguistics (1st ed.), New York: Oxford University Press

Template:Russian language Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter has terminated with signal "24".