Scheil equation

In metallurgy, the Scheil-Gulliver equation (or Scheil equation) describes solute redistribution during solidification of an alloy.

Assumptions

Four key assumptions in Scheil analysis enable determination of phases present in a cast part. These assumptions are:

- No diffusion occurs in solid phases once they are formed ()

- Infinitely fast diffusion occurs in the liquid at all temperatures by virtue of a high diffusion coefficient, thermal convection, Marangoni convection, etc. ()

- Equilibrium exists at the solid-liquid interface, and so compositions from the phase diagram are valid

- Solidus and liquidus are straight segments

The fourth condition (straight solidus/liquidus segments) may be relaxed when numerical techniques are used, such as those used in CALPHAD software packages, though these calculations rely on calculated equilibrium phase diagrams. Calculated diagrams may include odd artifacts (i.e. retrograde solubility) that influence Scheil calculations.

Derivation

Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination

The hatched areas in the figure represent the amount of solute in the solid and liquid. Considering that the total amount of solute in the system must be conserved, the areas are set equal as follows:

- .

Since the partition coefficient (related to solute distribution) is

- (determined from the phase diagram)

and mass must be conserved

the mass balance may be rewritten as

- .

Using the boundary condition

- at

the following integration may be performed:

- .

Integrating results in the Scheil-Gulliver equation for composition of the liquid during solidification:

or for the composition of the solid:

- .

Applications of the Scheil equation: Calphad Tools for the Metallurgy of Solidification

Nowadays, several Calphad softwares are available - in a framework of computational thermodynamics - to simulate solidification in systems with more than two components; these have recently been defined as Calphad Tools for the Metallurgy of Solidification. In recent years, Calphad-based methodologies have reached maturity in several important fields of metallurgy, and especially in solidification-related processes such as semi-solid casting, 3d printing, and welding, to name a few. While there are important studies devoted to the progress of Calphad methodology, there is still space for a systematization of the field, which proceeds from the ability of most Calphad-based software to simulate solidification curves and includes both fundamental and applied studies on solidification, to be substantially appreciated by a wider community than today. The three applied fields mentioned above could be widened by specific successful examples of simple modeling related to the topic of this issue, with the aim of widening the application of simple and effective tools related to Calphad and Metallurgy. See also "Calphad Tools for the Metallurgy of Solidification" in an ongoing issue of an Open Journal. https://www.mdpi.com/journal/metals/special_issues/Calphad_Solidification

Given a specific chemical composition, using a software for computational thermodynamics - which might be open or commercial - the calculation of the Scheil curve is possible if a thermodynamic database is available. A good point in favour of some specific commercial softwares is that the install is easy indeed and you can use it on a windows based system - for instance with students or for self training.

One should get some open, chiefly binary, databases (extension *.tdb), one could find - after registering - at Computational Phase Diagram Database (CPDDB) of the National Institute for Materials Science of Japan, NIMS https://cpddb.nims.go.jp/index_en.html. They are available - for free - and the collection is rather complete; in fact currently 507 binary systems are available in the thermodynamic data base (tdb) format. Some wider and more specific alloy systems partly open - with tdb compatible format - are available with minor corrections for Pandat use at Matcalc https://www.matcalc.at/index.php/databases/open-databases.

Numerical expression and numerical derivative of the Scheil curve: application to grain size on solidification and semi-solid processing

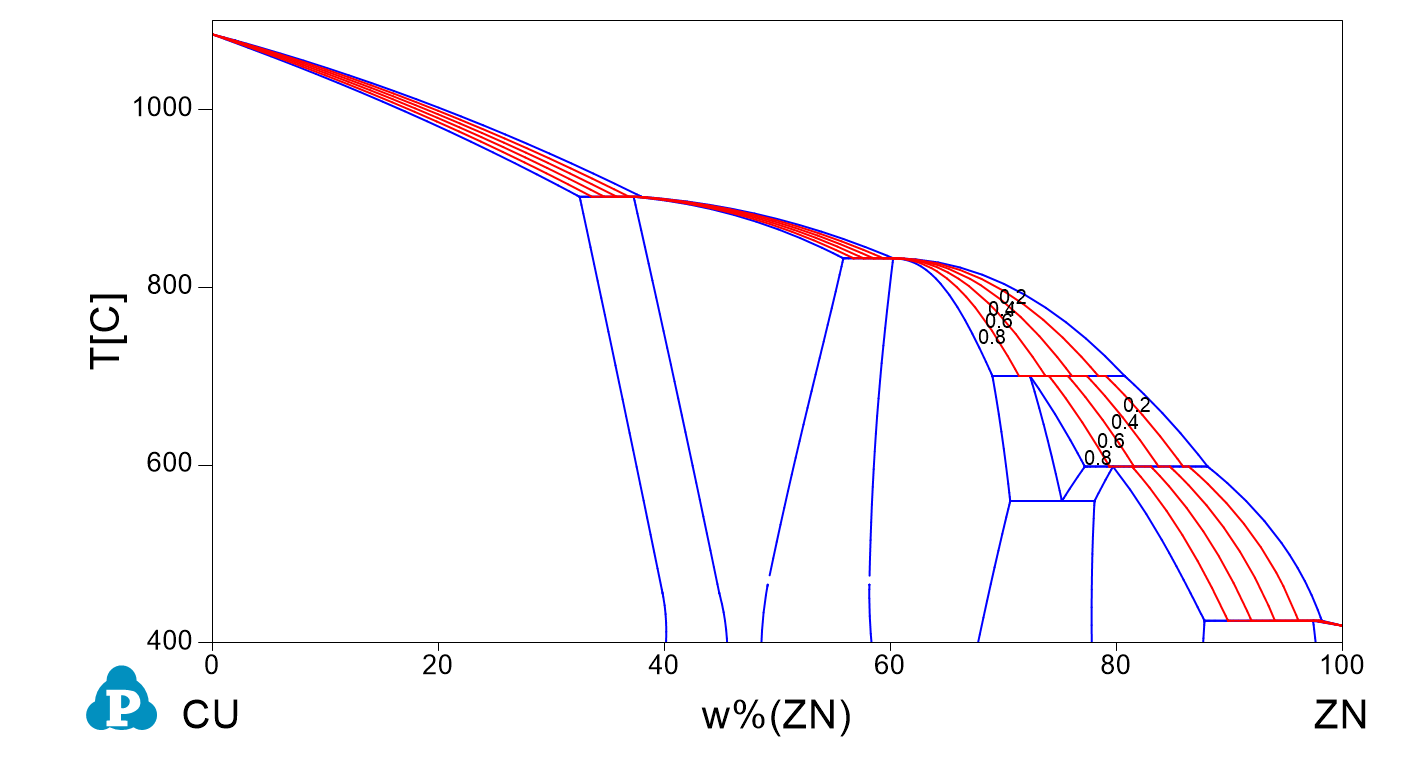

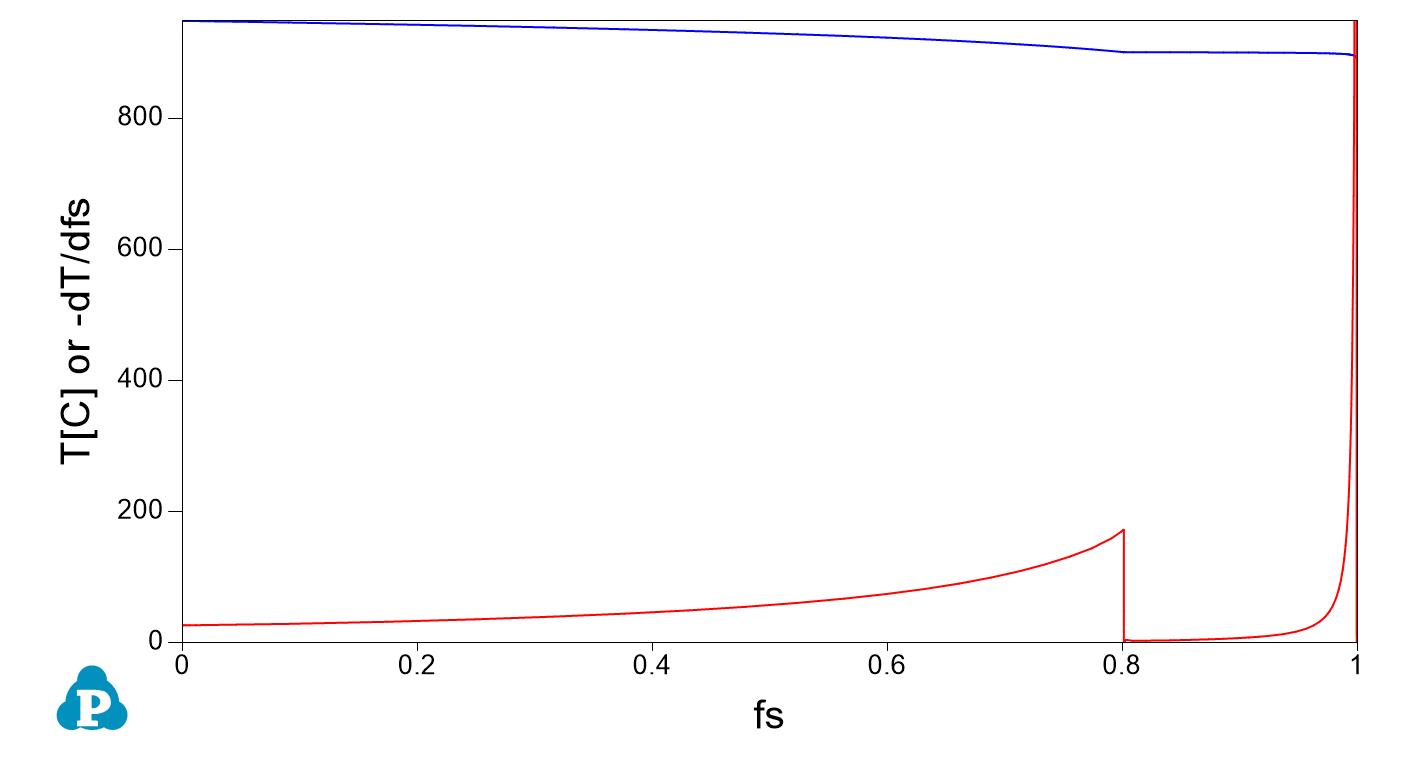

A key concept that might be used for applications is the (numerical) derivative of the solid fraction fs with temperature. A numerical example using a copper zinc alloy at composition Zn 30% in weight is proposed as an example here using the opposite sign for using both temperature and its derivative in the same graph.

Kozlov and Schmid-Fetzer have calculated numerically the derivative of the Scheil curve in an open paper https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/27/1/012001 and applied it to the growth restriction factor Q in Al-Si-Mg-Cu alloys.

Application to grain size on solidification

This - Calphad calculated value of numerical derivative - Q has some interesting applications in the field of metal solidification. In fact, Q reflects the phase diagram of the alloy system and its reciprocal has been found to have a relationship with grain size d on solidification, which empirically has been found in some cases to be linear:

where a and b are constants, as illustrated with some examples from the literature for Mg and Al alloys. Before Calphad use, Q values were calculated from the conventional relationship:

Q=m*c0(k−1)

where m is the slope of the liquidus, c0 is the solute concentration, and k is the equilibrium distribution coefficient.

More recently some other possible correlation of Q with grain size d have been found, for instance:

where B is a constant independent of alloy composition.

Application to solidification cracking

In recent publications, prof. Sindo Kou has proposed an approach to evaluate susceptibility to solidification cracking; this approach is based on a similar approach where a quantity, , which has the dimensions of a temperature is proposed as an index of the cracking susceptibility. Again one could exploit Scheil based solidification curves to link this index to the slope of the (Scheil) solidification curve: ∂T/(∂(fS)^1/2)= ∂T/(∂(fS)*(∂(fS)^1/2)/∂(fS))= (1/2)∂T/∂(fS)*(fS)^1/2=

Application to semi-solid processing

Last but not least prof. E.J.Zoqui has summarized in his work the approach proposed by several researchers in the criteria for semi-solid processing, which involves the stability of the solid phase fs with the temperature; to process semisolid alloys the sensitivity to variation of solid fraction with temperature should be minimal: in one direction it could evolve to a difficult to deform solid, on the other to a liquid which may be difficult to shape without proper moulding. It turns out that we can express this criterion again by evaluating the slope of the solidification curve, in fact ∂(fS)/∂T should be less than a certain threshold, which is commonly accepted in the scientific and technical literature to be below 0.03 1/K. Mathematically this may be expressed by an inequation , ∂(fS)/∂T < 0.03 (1/K) - where K stands for Kelvin degrees - could be equally assumed for a rough estimate of the two main semi-solid casting processing: both rheocasting ( 0.3<fs<0.4 ) and thixoforming (0.6<fs<0.7). If one would go back just to the (numerical) and functional approaches above, one should consider the reciprocal value i.e. ∂T/∂(fS)> 33 (K)

References

- Gulliver, G.H., The Quantitative Effect of Rapid Cooling Upon the Constitution of Binary Alloys, J. Inst. Met., 1913, 9, p 120-157

- Scheil, E., Bemerkungen zur Schichtkristallbildung, Z. Metallkd., 1942, 34, p 70-72

- Greer L., et al. Modelling of inoculation of metallic melts: application to grain refinement of aluminium by Al–Ti–B Acta Mat. 48, 11, 2000, 2823-2835 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1359-6454(00)00094-X

- Porter, D. A., and Easterling, K. E., Phase Transformations in Metals and Alloys (2nd Edition), Chapman & Hall, 1992. https://doi.org/10.1201/9781439883570

- Kou, S., Welding Metallurgy, 2nd Edition, Wiley -Interscience, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471434027

- Karl B. Rundman Principles of Metal Casting Textbook - Michigan Technological University

- Quested T.E., Dinsdale A.T. , Greer A.L. Thermodynamic modelling of growth-restriction effects in aluminium alloys Acta Materialia 53, 5, 2005, 1323-1334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actamat.2004.11.024

- H. Fredriksson, Y. Akerlind, Materials Processing during Casting, Chapter 7, Wiley, 2006. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Materials+Processing+During+Casting-p-9780470015148

- H. Fredriksson, Y. Akerlind, Materials Processing during Casting, Supplementary (open) Material https://www.wiley.com/legacy/wileychi/fredriksson/features.html

- Schmid-Fetzer, R. Phase Diagrams: The Beginning of Wisdom. J. Phase Equilib. Diffus. 35, 735–760, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11669-014-0343-5

- Zoqui, E. Alloys for Semisolid Processing, Comprehensive Materials Processing Volume 5, 2014, Pages 163-190 https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-096532-1.00520-3

- Zhang, D., Prasad, A., Bermingham, M.J. et al. Grain Refinement of Alloys in Fusion-Based Additive Manufacturing Processes. Metall Mater Trans A 51, 4341–4359 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-020-05880-4

- Todaro C.J., Easton M.A., Qiu D., Brandt M., StJohn D.H., Qian M. Grain refinement of stainless steel in ultrasound-assisted additive manufacturing, Additive Manufacturing 37, 2021,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addma.2020.101632

- Balart, M.J., Patel, J.B., Gao, F. et al. Grain Refinement of Deoxidized Copper. Metall Mater Trans A 47, 4988–5011 (2016) https://doi.org/10.1007/s11661-016-3671-8

- Kou, S. Predicting Susceptibility to Solidification Cracking and Liquation Cracking by CALPHAD, Metals 2021, 11(9), 1442 https://doi.org/10.3390/met11091442

- Zhang F., Liang S.,Zhang C. ,Chen S.,Lv D., Cao W., Kou S. Prediction of Cracking Susceptibility of Commercial Aluminum Alloys during Solidification, Metals 2021, 11(9), 1479; https://doi.org/10.3390/met11091479

External links

- "Computational Phase Diagram Database of the National Institute for Materials Science of Japan, NIMS". https://cpddb.nims.go.jp/en/. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- "Matcalc open databases". https://www.matcalc.at/index.php/databases/open-databases. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Performing Scheil-Gulliver analysis in MatCalc". https://www.matcalc-engineering.com/images/external/PDF-Files/scheil_gulliver.pdf. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

- "Special Issue "Calphad Tools for the Metallurgy of Solidification"". https://www.mdpi.com/journal/metals/special_issues/Calphad_Solidification. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- "Solidification Simulation by Scheil Model and Lever Rule". 3 March 2021. https://computherm.com/solidification-simulation-by-scheil-model-and-lever-rule. Retrieved 26 September 2021.

|