Shannon capacity of a graph

In graph theory, the Shannon capacity of a graph is a graph invariant defined from the number of independent sets of strong graph products. It is named after American mathematician Claude Shannon. It measures the Shannon capacity of a communications channel defined from the graph, and is upper bounded by the Lovász number, which can be computed in polynomial time. However, the computational complexity of the Shannon capacity itself remains unknown.

Graph models of communication channels

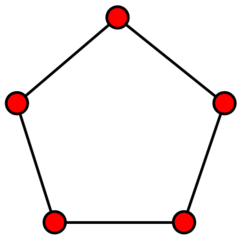

The Shannon capacity models the amount of information that can be transmitted across a noisy communication channel in which certain signal values can be confused with each other. In this application, the confusion graph[1] or confusability graph describes the pairs of values that can be confused. For instance, suppose that a communications channel has five discrete signal values, any one of which can be transmitted in a single time step. These values may be modeled mathematically as the five numbers 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 in modular arithmetic modulo 5. However, suppose that when a value is sent across the channel, the value that is received is (mod 5) where represents the noise on the channel and may be any real number in the open interval from −1 to 1. Thus, if the recipient receives a value such as 3.6, it is impossible to determine whether it was originally transmitted as a 3 or as a 4; the two values 3 and 4 can be confused with each other. This situation can be modeled by a graph, a cycle of length 5, in which the vertices correspond to the five values that can be transmitted and the edges of the graph represent values that can be confused with each other.

For this example, it is possible to choose two values that can be transmitted in each time step without ambiguity, for instance, the values 1 and 3. These values are far enough apart that they can't be confused with each other: when the recipient receives a value between 0 and 2, it can deduce that the value that was sent must have been 1, and when the recipient receives a value in between 2 and 4, it can deduce that the value that was sent must have been 3. In this way, in steps of communication, the sender can communicate up to different messages. Two is the maximum number of values that the recipient can distinguish from each other: every subset of three or more of the values 0, 1, 2, 3, 4 includes at least one pair that can be confused with each other. Even though the channel has five values that can be sent per time step, effectively only two of them can be used with this coding scheme.

However, more complicated coding schemes allow a greater amount of information to be sent across the same channel, by using codewords of length greater than one. For instance, suppose that in two consecutive steps the sender transmits one of the five code words "11", "23", "35", "54", or "42". (Here, the quotation marks indicate that these words should be interpreted as strings of symbols, not as decimal numbers.) Each pair of these code words includes at least one position where its values differ by two or more modulo 5; for instance, "11" and "23" differ by two in their second position, while "23" and "42" differ by two in their first position. Therefore, a recipient of one of these code words will always be able to determine unambiguously which one was sent: no two of these code words can be confused with each other. By using this method, in steps of communication, the sender can communicate up to messages, significantly more than the that could be transmitted with the simpler one-digit code. The effective number of values that can be transmitted per unit time step is . In graph-theoretic terms, this means that the Shannon capacity of the 5-cycle is at least . As (Lovász 1979) showed, this bound is tight: it is not possible to find a more complicated system of code words that allows even more different messages to be sent in the same amount of time, so the Shannon capacity of the 5-cycle is exactly .

Relation to independent sets

If a graph represents a set of symbols and the pairs of symbols that can be confused with each other, then a subset of symbols avoids all confusable pairs if and only if is an independent set in the graph, a subset of vertices that does not include both endpoints of any edge. The maximum possible size of a subset of the symbols that can all be distinguished from each other is the independence number of the graph, the size of its maximum independent set. For instance, ': the 5-cycle has independent sets of two vertices, but not larger.

For codewords of longer lengths, one can use independent sets in larger graphs to describe the sets of codewords that can be transmitted without confusion. For instance, for the same example of five symbols whose confusion graph is , there are 25 strings of length two that can be used in a length-2 coding scheme. These strings may be represented by the vertices of a graph with 25 vertices. In this graph, each vertex has eight neighbors, the eight strings that it can be confused with. A subset of length-two strings forms a code with no possible confusion if and only if it corresponds to an independent set of this graph. The set of code words {"11", "23", "35", "54", "42"} forms one of these independent sets, of maximum size.

If is a graph representing the signals and confusable pairs of a channel, then the graph representing the length-two codewords and their confusable pairs is , where the symbol represents the strong product of graphs. This is a graph that has a vertex for each pair of a vertex in the first argument of the product and a vertex in the second argument of the product. Two distinct pairs and are adjacent in the strong product if and only if and are identical or adjacent, and and are identical or adjacent. More generally, the codewords of length can be represented by the graph , the -fold strong product of with itself, and the maximum number of codewords of this length that can be transmitted without confusion is given by the independence number . The effective number of signals transmitted per unit time step is the th root of this number, .

Using these concepts, the Shannon capacity may be defined as

the limit (as becomes arbitrarily large) of the effective number of signals per time step of arbitrarily long confusion-free codes.

Computational complexity

| Unsolved problem in mathematics: What is the Shannon capacity of a 7-cycle? (more unsolved problems in mathematics)

|

The computational complexity of the Shannon capacity is unknown, and even the value of the Shannon capacity for certain small graphs such as (a cycle graph of seven vertices) remains unknown.[2][3]

A natural approach to this problem would be to compute a finite number of powers of the given graph , find their independence numbers, and infer from these numbers some information about the limiting behavior of the sequence from which the Shannon capacity is defined. However (even ignoring the computational difficulty of computing the independence numbers of these graphs, an NP-hard problem) the unpredictable behavior of the sequence of independence numbers of powers of implies that this approach cannot be used to accurately approximate the Shannon capacity.[4]

Upper bounds

In part because the Shannon capacity is difficult to compute, researchers have looked for other graph invariants that are easy to compute and that provide bounds on the Shannon capacity.

Lovász number

The Lovász number ϑ(G) is a different graph invariant, that can be computed numerically to high accuracy in polynomial time by an algorithm based on the ellipsoid method. The Shannon capacity of a graph G is bounded from below by α(G), and from above by ϑ(G).[5] In some cases, ϑ(G) and the Shannon capacity coincide; for instance, for the graph of a pentagon, both are equal to √5. However, there exist other graphs for which the Shannon capacity and the Lovász number differ.[6]

Haemers' bound

Haemers provided another upper bound on the Shannon capacity, which is sometimes better than Lovász bound:[7]

where B is an n × n matrix over some field, such that bii ≠ 0 and bij = 0 if vertices i and j are not adjacent.

References

- ↑ Erickson, Martin J. (2014). Introduction to Combinatorics. Discrete Mathematics and Optimization. 78 (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 134. ISBN 978-1118640210.

- ↑ Regan, Kenneth W. (July 10, 2013), "Rough problems", Gödel's Lost Letter and P=NP, http://rjlipton.wordpress.com/2013/07/10/rough-problems/.

- ↑ tchow (February 19, 2009), "Shannon capacity of the seven-cycle", Open Problem Garden, http://www.openproblemgarden.org/op/shannon_capacity_of_the_seven_cycle.

- ↑ Alon, Noga; Lubetzky, Eyal (2006), "The Shannon capacity of a graph and the independence numbers of its powers", IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 52 (5): 2172–2176, doi:10.1109/tit.2006.872856.

- ↑ Lovász, László (1979), "On the Shannon Capacity of a Graph", IEEE Transactions on Information Theory IT-25 (1): 1–7, doi:10.1109/TIT.1979.1055985.

- ↑ Haemers, Willem H. (1979), "On Some Problems of Lovász Concerning the Shannon Capacity of a Graph", IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 25 (2): 231–232, doi:10.1109/tit.1979.1056027, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/3083183.

- ↑ Haemers, Willem H. (1978), "An upper bound for the Shannon capacity of a graph", Colloquia Mathematica Societatis János Bolyai 25: 267–272, https://pure.uvt.nl/portal/files/997000/UPPER___.PDF. The definition here corrects a typo in this paper.

|