Social:Dehumanization

Dehumanization is the process, practice, or act of denying full humanity in others,[1] along with the cruelty and suffering that accompany it.[2][3][4] It involves perceiving individuals or groups as lacking essential human qualities, such as secondary emotions and mental capacities, thereby placing them outside the bounds of moral concern.[1] In this definition, any act or thought that regards a person as either "other than" and "less than" human constitutes dehumanization.[5][6]

Dehumanization can be overt or subtle,[7] and typically manifests in two primary forms: animalistic dehumanization, which denies uniquely human traits like civility, culture, or rationality and likens others to animals;[3] and mechanistic dehumanization, which denies traits of human nature such as warmth, emotion, and individuality, portraying others as objects or machines.[3]

It has historically facilitated a broad range of harms, from discrimination and social exclusion to slavery,[1] colonization,[8] as well as other crimes against humanity,[1] and is recognized as a significant form of incitement to genocide.[9]

Conceptualizations

Behaviorally, dehumanization describes a disposition towards others that debases the others' individuality by either portraying it as an "individual" species or by portraying it as an "individual" object (e.g., someone who acts inhumanely towards humans). As a process, dehumanization may be understood as the opposite of personification, a figure of speech in which inanimate objects or abstractions are endowed with human qualities; dehumanization then is the disendowment of these same qualities or a reduction to abstraction.[10]

Dehumanization can occur in both absolute and relative forms.[11] Absolute dehumanization involves perceiving a group as entirely devoid of human qualities, while relative dehumanization entails attributing fewer human characteristics to one group in comparison to another.[11] Historically, dehumanization has involved the outright denial of someone's humanity, such as in claims that certain groups, like enslaved people, were not fully human.[1] It can also portray others as less human, such as through the objectification of women or the demonization of migrants.[1] Both forms are understood as expressions of dehumanization, differing primarily in the extent to which human attributes are denied.[11]

This distinction relates to the difference between blatant and subtle forms of dehumanization.[11] Blatant dehumanization typically involves overt and explicit comparisons to animals or other non-human entities, often verbalized through direct language.[12] In contrast, subtle dehumanization, often referred to as infrahumanization, manifests in the implicit belief that members of out-groups possess fewer uniquely human emotions or traits.[11] These processes may occur unconsciously.[12] Early studies on dehumanization focused primarily on its blatant forms, particularly in the context of intergroup conflicts.[11] However, subsequent research has indicated that dehumanization could also occur in more subtle ways, even in the absence of overt hostility.[11] Moreover, although traditionally associated with dominant or oppressive groups within hierarchical structures, research indicates that dehumanization can occur reciprocally, including amongst oppressed or disadvantaged groups.[13]

Animalistic and mechanistic dehumanization are further distinguished based on their distinct psychological underpinnings, which influence the contexts in which dehumanization occurs and the forms of harm it may motivate.[14] Also, the distinction between animalistic and mechanistic dehumanization lies not only in their content but also in the typical contexts of application.[15] Animalistic dehumanization is primarily observed on intergroup dynamics,[15] where individuals or groups are seen as lacking culture, civility, or rationality, traits thought to separate humans from animals.[16] In contrast, mechanistic dehumanization tends to occur in interpersonal settings,[15] where people are perceived as lacking emotionality, warmth, and other qualities associated with lived beings,[11] akin to robots and machines.[1] Although animalistic and mechanistic dehumanization are often presented as distinct dimensions, they are not mutually exclusive; in some cases, individuals or groups may be denied traits associated with both.[11]

Dehumanization is widely understood as a psychological mechanism that facilitates violence and inhumane treatment.[1] It plays a central role in justifying harm by removing the moral consideration typically granted to human beings, thereby weakening psychological restraints such as compassion and empathy.[11] One component of this process is the denial of others' mental states, known as "dementalization," which contributes to their moral exclusion and increases the likelihood of mistreatment.[11] Scholars distinguish dehumanization from related psychological phenomena such as dislike, as it entails the denial of a person's moral and mental worth, adding a particularly harmful layer by diminishing the relevance of their suffering.[17] Unlike people who are stigmatized or marginalized but still recognized as normatively human, individuals who are dehumanized are perceived as fundamentally lacking in essential human qualities and moral worth.[18] This distinction is significant because moral inclusion often imposes limits on how individuals may be treated, whereas dehumanization removes such constraints, enabling more extreme forms of violence and exclusion.[18]

Although dehumanization is a significant factor in enabling violent behaviour, scholars emphasize that it is not sufficient on its own to explain all instances of violence.[1] Research indicates a strong association between dehumanization and increased levels of aggression, and it can be used to justify or sustain acts of violence and long-term animosity.[19] It may also intensify intergroup conflict by sharpening distinctions between in-groups and out-groups.[20] Beyond its role in facilitating violence, dehumanization can serve several social and psychological functions. These include legitimizing harm such as exploitation, submission, or killing by reducing moral restraint, managing existential anxieties through the projection of one's fears and vulnerabilities, and reinforcing social stratification or defending the status quo.[1]

According to Adrienne De Ruiter, dehumanization occurs in three manifestations: through the failure to perceive individuals as human, the portrayal of them in ways that disregard their humanity, or the treatment of them in ways that diminish their human qualities.[18] These manifestations can occur discursively (e.g., idiomatic language that likens individual human beings to non-human animals, verbal abuse, erasing one's voice from discourse), symbolically (e.g., imagery), or physically (e.g., chattel slavery, physical abuse, refusing eye contact). Dehumanization often ignores the target's individuality (i.e., the creative and exciting aspects of their personality) and can hinder one from feeling empathy or correctly understanding a stigmatized group.[21]

Dehumanization has been examined across various disciplines as a mechanism that reinforces social hierarchies and exclusion.[17] Dehumanization may be carried out by a social institution (such as a state, school, or family), interpersonally, or even within oneself. Dehumanization can be unintentional, especially upon individuals, as with some types of de facto racism. State-organized dehumanization has historically been directed against certain political, racial, ethnic, national, or religious minority groups. Other minoritized and marginalized individuals and groups (based on sexual orientation, gender, disability, class, or some other organizing principle) are also susceptible to various forms of dehumanization. The concept of dehumanization has received empirical attention in the psychological literature.[22][23] Besides infrahumanization,[24] it is conceptually related to delegitimization,[25] moral exclusion,[26] and objectification.[27]

Humanness

In Herbert Kelman's work on dehumanization, humanness has two features: "identity" (i.e., a perception of the person "as an individual, independent and distinguishable from others, capable of making choices") and "community" (i.e., a perception of the person as "part of an interconnected network of individuals who care for each other"). When a target's agency and embeddedness in a community are denied, they no longer elicit compassion or other moral responses and may suffer violence.[28]

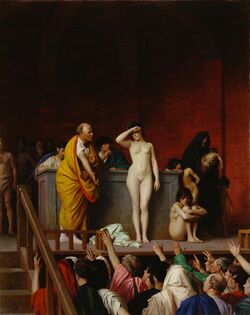

Objectification

Psychologist Barbara Fredrickson and Tomi-Ann Roberts argued that the sexual objectification of women extends beyond pornography (which emphasizes women's bodies over their uniquely human mental and emotional characteristics) to society generally. There is a normative emphasis on female appearance that causes women to take a third-person perspective on their bodies.[29] The psychological distance women may feel from their bodies might cause them to dehumanize themselves. Some research has indicated that women and men exhibit a "sexual body part recognition bias", in which women's sexual body parts are better recognized when presented in isolation than in their entire bodies. In contrast, men's sexual body parts are better recognized in the context of their entire bodies than in isolation.[30] Men who dehumanize women as either animals or objects are more liable to rape and sexually harass women and display more negative attitudes toward female rape victims.[31]

Philosopher Martha Nussbaum identified seven components of sexual objectification: instrumentality, denial of autonomy, inertness, fungibility, violability, ownership, and denial of subjectivity.[32] In this context, instrumentality refers to when the objectified is used as an instrument to the objectifier's benefit. Denial of autonomy occurs in the form of the objectifier underestimating the objectified and denies their capabilities. In the case of inertness, the objectified is treated as if they are lazy and indolent. Fungibility brands the objectified to be easily replaceable. Volability is when the objectifier does not respect the objectified person's personal space or boundaries. Ownership is when the objectified is seen as another person's property. Lastly, the denial of subjectivity is a lack of sympathy for the objectified, or the dismissal of the notion that the objectified has feelings. These seven components cause the objectifier to view the objectified in a disrespectful way, therefore treating them so.[33]

History

The term dehumanization first appeared in English in the early 19th century, initially referring to changes in physical appearance, but it soon broadened to describe forms of social and moral degradation.[34] While the term itself is modern, critiques of practices that would now be recognized as dehumanizing, such as slavery, can be traced back to classical antiquity. In ancient Greece, for instance, Aristotle's defense of natural slavery responded to contemporary philosophical debates about the moral status of slaves.[35] His arguments were later invoked to justify the dehumanization of Native Americans during the Spanish conquest and colonization.[35]

The idea of universal human worth gradually gained prominence through what scholars call the invention of humanity, a historical process that gained momentum during the Enlightenment and promoted the belief in a shared human essence.[34] However, as awareness of common humanity grew, so too did the ideological efforts to exclude certain groups from its scope, often through pseudo-scientific racial theories.[36] Dehumanization became a powerful tool during the age of colonialism, enabling imperial powers to justify the colonization, enslavement, and extermination of subjugated peoples.[37]

Throughout history, societies have engaged in and institutionalized this denial of humanity to enable mass oppression, exploitation, and killing.[38] By portraying colonized groups as less than fully human, dominant groups were able to morally disengage from the suffering they inflicted, facilitating acts of exploitation, violence, and oppression.[39] David Livingstone Smith, director and founder of The Human Nature Project at the University of New England, argues that historically, human beings have been dehumanizing one another for thousands of years.[40] In his work "The Paradoxes of Dehumanization", Smith proposes that dehumanization simultaneously regards people as human and subhuman. This paradox comes to light, as Smith identifies, because the reason people are dehumanized is so their human attributes can be taken advantage of.[41]

Modern scholarly interest in dehumanization intensified after World War II, especially in response to the Holocaust, with influential contributions from thinkers such as Hannah Arendt.[34] During the Cold War and especially the Vietnam War, the concept became central to interdisciplinary research, spanning psychology, sociology, philosophy, genocide studies, and conflict analysis, as an important mechanism underlying social exclusion, violence, and moral disengagement.[34]

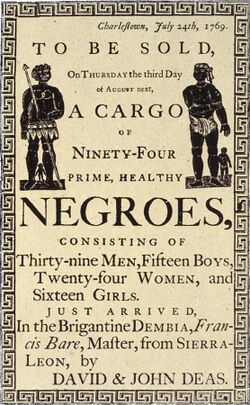

Transatlantic slave trade

Dehumanization played a central role in justifying and sustaining the transatlantic slave trade.[42] Africans were portrayed as biologically suited for enslavement and were denied the qualities considered essential to full humanity.[43] This logic was grounded in binary oppositions, especially the division between the "civilized" and the "savage", in which enslaved peoples were depicted as savages lacking rationality, culture, and moral agency.[44] Such portrayals served to legitimize their exploitation and subjugation.[44] These beliefs were later reinforced by ideologies that framed imperial powers as bearers of civilization to "less developed" peoples, a view often encapsulated in the phrase "the White Man's Burden".[45]

Native Americans

Native Americans were dehumanized as "merciless Indian savages" in the United States Declaration of Independence.[47] Two sculptures reflecting this view of the Natives were commissioned by the U.S. government and stood outside the U.S. Capitol from 1844 to 1958: The Discovery of America which depicted a triumphant Columbus and a "female savage", according to the Pennsylvania senator James Buchanan who proposed the sculpture,[48] and The Rescue whose sculptor Horatio Greenough wrote that it was "to convey the idea of the triumph of the whites over the savage tribes".[49] Following the Wounded Knee massacre in December 1890, author L. Frank Baum wrote:[50]

The Pioneer has before declared that our only safety depends upon the total extermination [sic] of the Indians. Having wronged them for centuries we had better, in order to protect our civilization, follow it up by one more wrong and wipe these untamed and untamable creatures from the face of the earth. In this lies safety for our settlers and the soldiers who are under incompetent commands. Otherwise, we may expect future years to be as full of trouble with the redskins as those have been in the past.

In Martin Luther King Jr.'s book on civil rights, Why We Can't Wait, he wrote:[51][52][53]

Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrine that the original American, the Indian, was an inferior race. Even before there were large numbers of Negroes on our shores, the scar of racial hatred had already disfigured colonial society. From the sixteenth century forward, blood flowed in battles over racial supremacy. We are perhaps the only nation which tried as a matter of national policy to wipe out its indigenous population. Moreover, we elevated that tragic experience into a noble crusade. Indeed, even today we have not permitted ourselves to reject or to feel remorse for this shameful episode. Our literature, our films, our drama, our folklore all exalt it.

King was an active supporter of the Native American rights movement, which he drew parallels with his own leadership of the civil rights movement.[53] Both movements aimed to overturn dehumanizing attitudes held by members of the public at large against them.[54]

Nazi Germany

Dehumanization reached one of its most extreme expressions under Nazi Germany, where it was systematically employed to justify and implement the persecution and extermination of various groups, including Jews, Romani and Sinti people, people with disabilities, political dissidents, and LGBTQ+ individuals.[55] The Holocaust is regarded as one of the most systematic and historically significant examples of atrocities carried out through sustained processes of dehumanization.[56]

Nazi Germany institutionalized dehumanization through the construction of legal and bureaucratic structures that explicitly denied the full humanity of targeted populations.[56] Legal frameworks played a central role in this process, with laws such as the Nuremberg Laws, codifying discriminatory categories and racial hierarchies that legitimized exclusion, persecution, and ultimately extermination.[57] The Nazi regime also employed mass media and state propaganda to disseminate dehumanizing imagery and rhetoric that depicted these groups as subhuman threats to the German nation.[58]

Jews were frequently portrayed through animalistic metaphors, including comparisons to vermin, and framed as biologically impure threats to racial purity.[58] The term Untermensch (subhuman) was used to deny Jews and others moral standing and membership to the human community.[58] In an October 1943 speech, Heinrich Himmler framed the extermination of the Jewish people as a historical mission, specifically comparing the Jews to a bacillus, reinforcing the portrayal of Jews as a dangerous disease that needs to be eradicated.[59] These dehumanizing narratives facilitated the systematic extermination of 6,000,000 Jews during the Holocaust at the hands of the nazis.[58] In addition, a state-sponsored eugenics program, most notably through Aktion T4, targeted individuals with disabilities or others deemed possessing a life unworthy of life.[58] These individuals were deemed inferior and a threat to the purity of the Aryan race, and were also systematically exterminated.[58]

Israelis and Palestinians

Dehumanization has been a persistent and influential factor in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, contributing to intergroup hostility and serving as a strong predictor of support for violence across both societies.[60] In protracted conflicts by high levels of insecurity and entrenched group identities, boundaries between in-groups and out-groups often become more rigid, which reinforces psychological separation and facilitates dehumanizing attitudes.[61] Dehumanization has been identified as a central mechanism in sustaining violence in protracted conflicts, which reinforces collective victimhood identities, legitimizes hostility and perpetuates cycles of violence and retaliation.[62]

Empirical research has found that both Palestinian and Jewish Israeli participants who expressed dehumanizing views of the other group were more likely to support retributive forms of justice and violent measures, as opposed to restorative or conciliatory approaches.[63] Historical examples of dehumanization in Israeli society include comparing Palestinians to the biblical "sons of Amalek", a tribal group portrayed as inherently evil.[64] Dehumanization contributes to the justification of exclusionary and violent policies, with studies linking dehumanizing attitudes to public support for measures such as population transfers amongst segments of the Israeli population.[63] Dehumanizing narratives have also historically appeared in nationalist slogans, such as the early Zionist phrase "a land without a people for a people without a land", which is interpreted as a symbolic erasure of Palestinian peoplehood.[65] Dehumanization has been used not only to deny the humanity of Palestinians but also to undermine their historical presence on the lands.[66]

During the 2014 Gaza War, studies found high and comparable levels of blatant dehumanization among both Israeli and Palestinian participants.[67] A survey using the "ascent of man scale",[68] a common measure of dehumanizing attitudes, found that, on average, both sides rated each other closer to an animal than a fully evolved human when shown a March of Progress image.[69] On the scale with "0 corresponding to the left side of the image (i.e., quadrupedal human ancestor), and 100 corresponding to the right side of the image ('full' modern-day human)"[70] Israelis on average rated Palestinians 39.81 points lower than their own group and Palestinians on average rated Israelis 37.03 points lower than their own group.[69]

Following the Hamas attacks on October 7, 2023, dehumanizing language intensified in Israeli political discourse.[67] Senior officials used animalistic dehumanization through metaphors, such as "rats" and "cockroaches", to describe Palestinians in Gaza, which served to legitimize acts of violence.[66] These statements have drawn international scrutiny and were cited in legal proceedings at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) concerning allegations of incitement to genocide.[65] Dehumanizing content also circulates widely on social media. In Israel, such rhetoric targets not only Palestinians but also left-wing Jewish Israelis, who have been depicted in demonizing and animalistic terms, including "dogs", "microbes", and "vermin".[71] Political orientation has also been shown to influence levels of dehumanization, with research indicating that right-wing Israelis are more likely to dehumanize Palestinians than left-wing Israelis.[63]

Dehumanizing zoomorphisms are found in both Israeli discourse and Palestinian discourse. During South Africa's submission to the ICJ that Israel was committing genocide against the Palestinians, the president of the ICJ cited Yoav Gallant for using the phrase "human animals" in reference to Palestinians.[72] On the Palestinian side, dehumanization has also been linked to support for violence.[62] According to Joana Ricarte, dehumanizing perceptions of Israelis have contributed to moral frameworks that legitimized violence, including the attacks of October 7 2023.[62]

Causes and facilitating factors

Several lines of psychological research relate to the concept of dehumanization. Infrahumanization suggests that individuals think of and treat out-group members as "less human" and more like animals;[24] while Austrian ethnologist Irenäus Eibl-Eibesfeldt uses the term pseudo-speciation, a term that he borrowed from the psychoanalyst Erik Erikson, to imply that the dehumanized person or persons are regarded as not members of the human species.[73] Specifically, individuals associate secondary emotions (which are seen as uniquely human) more with the in-group than with the out-group. Primary emotions (those experienced by all sentient beings, whether human or other animals) are found to be more associated with the out-group.[24] Dehumanization is intrinsically connected with violence.[74][75][76] Often, one cannot do serious injury to another without first dehumanizing him or her in one's mind (as a form of rationalization).[77] Military training is, among other things, systematic desensitization and dehumanization of the enemy, and military personnel may find it psychologically necessary to refer to the enemy as an animal or other non-human beings. Lt. Col. Dave Grossman has shown that without such desensitization it would be difficult, if not impossible, for one human to kill another human, even in combat or under threat to their own lives.[78]

According to Daniel Bar-Tal, delegitimization is the "categorization of groups into extreme negative social categories which are excluded from human groups that are considered as acting within the limits of acceptable norms and values".[25]

Moral exclusion occurs when out-groups are subject to a different set of moral values, rules, and fairness than are used in social relations with in-group members.[26] When individuals dehumanize others, they no longer experience distress when they treat them poorly. Moral exclusion is used to explain extreme behaviors like genocide, harsh immigration policies, and eugenics, but it can also happen on a more regular, everyday discriminatory level. In laboratory studies, people who are portrayed as lacking human qualities are treated in a particularly harsh and violent manner.[79][80][81][clarification needed]

Dehumanized perception occurs when a subject experiences low frequencies of activation within their social cognition neural network.[82] This includes areas of neural networking such as the superior temporal sulcus (STS) and the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).[83] A 2001 study by psychologists Chris and Uta Frith suggests that the criticality of social interaction within a neural network has tendencies for subjects to dehumanize those seen as disgust-inducing, leading to social disengagement.[84] Tasks involving social cognition typically activate the neural network responsible for subjective projections of disgust-inducing perceptions and patterns of dehumanization. "Besides manipulations of target persons, manipulations of social goals validate this prediction: Inferring preference, a mental-state inference, significantly increases mPFC and STS activity to these otherwise dehumanized targets."Template:Whose quote[85] A 2007 study by Harris, McClure, van den Bos, Cohen, and Fiske suggests that a person's choice to dehumanize another person is due to decreased neural activity towards the projected target. This decreased neural activity is identified as low medial prefrontal cortex activation, which is associated with perceiving social information.[incomprehensible][86]

While social distance from the out-group target is a necessary condition for dehumanization, some research suggests that this alone is insufficient. Psychological research has identified high status, power, and social connection as additional factors. Members of high-status groups more often associate humanity with the in-group than the out-group, while members of low-status groups exhibit no differences in associations with humanity. Thus, having a high status makes one more likely to dehumanize others.[87] Low-status groups are more associated with human nature traits (e.g., warmth, emotionalism) than uniquely human characteristics, implying that they are closer to animals than humans because these traits are typical of humans but can be seen in other species.[88] In addition, another line of work found that individuals in a position of power were more likely to objectify their subordinates, treating them as a means to one's end rather than focusing on their essentially human qualities.[89] Finally, social connection—thinking about a close other or being in the actual presence of a close other—enables dehumanization by reducing the attribution of human mental states, increasing support for treating targets like animals, and increasing willingness to endorse harsh interrogation tactics.[90] This is counterintuitive because social connection has documented personal health and well-being benefits but appears to impair intergroup relations.

Neuroimaging studies have discovered that the medial prefrontal cortex—a brain region distinctively involved in attributing mental states to others—shows diminished activation to extremely dehumanized targets (i.e., those rated, according to the stereotype content model, as low-warmth and low-competence, such as drug addicts or homeless people).[91][92]

Race and ethnicity

Racist dehumanization entails that groups and individuals are understood as less than fully human by virtue of their race.[93]

Dehumanization often occurs as a result of intergroup conflict. Ethnic and racial others are often represented as animals in popular culture and scholarship. There is evidence that this representation persists in the American context with African Americans implicitly associated with apes. To the extent that an individual has this dehumanizing implicit association, they are more likely to support violence against African Americans (e.g., jury decisions to execute defendants).[94] Historically, dehumanization is frequently connected to genocidal conflicts in that ideologies before and during the conflict depict victims as subhuman (e.g., rodents).[95] Immigrants may also be dehumanized in this manner.[96]

In 1901, the six Australian colonies assented to federation, creating the modern nation state of Australia and its government. Section 51 (xxvi) excluded Aboriginals from the groups protected by special laws, and section 127 excluded Aboriginals from population counts. The Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 categorically denied Aboriginals the right to vote. Indigenous Australians were not allowed the social security benefits (e.g., aged pensions and maternity allowances) which were provided to others. Aboriginals in rural areas were discriminated against and controlled as to where and how they could marry, work, live, and their movements.[97]

In the U.S., African Americans were dehumanized by being classified as non-human primates. A California police officer who was also involved in the Rodney King beating described a dispute between an American Black couple as "something right out of Gorillas in the Mist".[98] Franz Boas and Charles Darwin hypothesized that there might be an evolutionary process among primates. Monkeys and apes were least evolved, then savage and deformed anthropoids, which referred to people of African ancestry, to Caucasians as most developed.[99]

Language

Language has been used as an essential tool in the process of dehumanizing others.[100][101] Examples of dehumanizing language when referring to a person or group of people may include animal, cockroach, rat, vermin, monster, ape, snake, infestation, parasite, alien, savage, and subhuman. Other examples can include racist, sexist, and other derogatory forms of language.[101] The use of dehumanizing language can influence others to view a targeted group as less human or less deserving of humane treatment.[100]

In Unit 731, an imperial Japanese biological and chemical warfare research facility, brutal experiments were conducted on humans who the researchers referred to as 'maruta' (丸太) meaning logs.[102][103] Yoshio Shinozuka, Japanese army medic who performed several vivisections in the facility said, "We called the victims 'logs.' We didn't want to think of them as people. We didn't want to admit that we were taking lives. So we convinced ourselves that what we were doing was like cutting down a tree."[104][103]

Words such as migrant, immigrant, and expatriate are assigned to foreigners based on their social status and wealth, rather than ability, achievements, or political alignment. Expatriate is a word to describe the privileged, often light-skinned people newly residing in an area and has connotations that suggest ability, wealth, and trust. Meanwhile, the word immigrant is used to describe people coming to a new location to reside and infers a much less-desirable meaning.[105]

The word "immigrant" is sometimes paired with "illegal", which harbors a profoundly derogatory connotation. Misuse of these terms—they are often used inaccurately—to describe the other, can alter the perception of a group as a whole in a negative way. Ryan Eller, the executive director of the immigrant advocacy group Define American, expressed the problem this way:[106]

It's not just because it's derogatory, but because it's factually incorrect. Most of the time when we hear [illegal immigrant] used, most of the time, the shorter version 'illegals' is being used as a noun, which implies that a human being is perpetually illegal. There is no other classification that I'm aware of where the individual is being rendered as unlawful as opposed to those individuals' actions.

A series of language examinations found a direct relation between homophobic epithets and social cognitive distancing towards a group of homosexuals, a form of dehumanization. These epithets (e.g., faggot) were thought to function as dehumanizing labels because they tended to act as markers of deviance. One pair of studies found that subjects were more likely to associate malignant language with homosexuals, and that such language associations increased the physical distancing between the subject and the homosexual. This indicated that the malignant language could encourage dehumanization, cognitive and physical distancing in ways that other forms of malignant language do not.[107] Another study involved a computational linguistic analysis of dehumanizing language regarding LGBTQ individuals and groups in the New York Times from 1986 to 2015.[108] The study used previous psychological research on dehumanization to identify four language categories: (1) negative evaluations of a target group, (2) denial of agency, (3) moral disgust, and (4) likening members of the target group to non-human entities (e.g., machines, animals, vermin). The study revealed that LGBTQ people overall have been increasingly more humanized over time; however, they were found to be humanized less frequently than the New York Time's in-group identifier American.[108]

Aliza Luft notes that the role of dehumanizing language and propaganda plays in violence and genocide is far less significant than other factors such as obedience to authority and peer pressure.[109]

Property takeover

Property scholars define dehumanization as "the failure to recognize an individual's or group's humanity."[110] Dehumanization often occurs alongside property confiscation. When a property takeover is coupled with dehumanization, the result is a dignity taking.[110] There are several examples of dignity takings involving dehumanization.

From its founding, the United States repeatedly engaged in dignity takings from Native American populations, taking indigenous land in an "undeniably horrific, violent, and tragic record" of genocide and ethnocide.[111] As recently as 2013, the degradation of a mountain sacred to the Hopi people—by spraying its peak pot with artificial snow made from wastewater—constituted another dignity taking by the U.S. Forest Service.[111]

The 1921 Tulsa race massacre also constituted a dignity taking involving dehumanization.[112] White rioters dehumanized African Americans by attacking, looting, and destroying homes and businesses in Greenwood, a predominantly Black neighborhood known as "Black Wall Street".[112]

During the Holocaust, mass genocide—a severe form of dehumanization—accompanied the destruction and taking of Jewish property.[113] This constituted a dignity taking.[113]

Jewish settlers in the West Bank have been criticized for dehumanizing Palestinians and land grabbing on illegal settlements.[114] These illegal settlement activities involve systemic settler violence against Palestinians, military orders, and state-sanctioned support.[115] These actions force Palestinians to gradually give up their land and farming activities and gradually choke their sources of dignified income.[115] Israeli soldiers sometimes actively participate in violence against civilians or look on from the sidelines.[115]

Undocumented workers in the United States have also been subject to dehumanizing dignity takings when employers treat them as machines instead of people to justify dangerous working conditions.[116] When harsh conditions lead to bodily injury or death, the property destroyed is the physical body.[116]

Media-driven dehumanization

The propaganda model of Edward S. Herman and Noam Chomsky argues that corporate media are able to carry out large-scale, successful dehumanization campaigns when they promote the goals (profit-making) that the corporations are contractually obliged to maximize.[117][118] State media are also capable of carrying out dehumanization campaigns, whether in democracies or dictatorships, which are pervasive enough that the population cannot avoid the dehumanizing memes.[117]

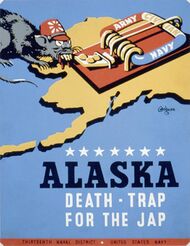

War propaganda

National leaders use dehumanizing propaganda to sway public opinion in favor of the military elite's agenda or cause and to repel criticism and proper oversight. The Bush Jr administration used dehumanizing rhetoric to describe Arabs and Muslims collectively as backwards, violent fanatics who "hate us for our freedom" to justify his invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq and covert CIA operations in the Middle East and Africa.[119] The media propaganda portrayed Arabs as a "monolithic evil" in the perception of the unwitting American public.[119] They employed news, media, language, magazine stories, television, and popular culture to portray all Muslims as Arab and all Arabs as violent terrorists which must be feared, fought, and destroyed. Racism was also used by portraying all Arabs as dark-skinned and thus racially inferior and untrustworthy.[119]

Non-state actors

Non-state actors—terrorists in particular—have also resorted to dehumanization to further their cause. The 1960s terrorist group Weather Underground had advocated violence against any authority figure and used the "police are pigs" meme to convince members that they were not harming human beings but merely killing wild animals. Likewise, rhetoric statements such as "terrorists are just scum", is an act of dehumanization.[120]

In science, medicine, and technology

Relatively recent history has seen the relationship between dehumanization and science result in unethical scientific research. The Tuskegee syphilis experiment, Unit 731, and Nazi human experimentation on Jewish people are three such examples. In the former, African Americans with syphilis were recruited to participate in a study about the course of the disease. Even when treatment and a cure were eventually developed, they were withheld from the African-American participants so that researchers could continue their study. Similarly, Nazi scientists during the Holocaust conducted horrific experiments on Jewish people and Shirō Ishii's Unit 731 also did so to Chinese, Russian, Mongolian, American, and other nationalities held captive. Both were justified in the name of research and progress, which is indicative of the far-reaching effects that the culture of dehumanization had upon this society. When this research came to light, efforts were made to protect future research participants, and currently, institutional review boards exist to safeguard individuals from being exploited by scientists.

In biological terms, dehumanization can be described as an introduced species marginalizing the human species, or an introduced person/process that debases other people inhumanely.[121]

In political science and jurisprudence, the act of dehumanization is the inferential alienation of human rights or denaturalization of natural rights, a definition contingent upon presiding international law rather than social norms limited by human geography. In this context, a specialty within species does not need to constitute global citizenship or its inalienable rights; the human genome inherits both. [original research?]

In a medical context, some dehumanizing practices have become more acceptable. While the dissection of human cadavers was seen as dehumanizing in the Dark Ages (see history of anatomy), the value of dissections as a training aid is such that they are now more widely accepted. Dehumanization has been associated with modern medicine generally and has explicitly been suggested as a coping mechanism for doctors who work with patients at the end of life.[95][122] Researchers have identified six potential causes of dehumanization in medicine: deindividuating practices, impaired patient agency, dissimilarity (causes which do not facilitate the delivery of medical treatment), mechanization, empathy reduction, and moral disengagement (which could be argued to facilitate the delivery of medical treatment).[123]

In some US states, legislation requires that a woman view ultrasound images of her fetus before having an abortion. Critics of the law argue that merely seeing an image of the fetus humanizes it and biases women against abortion.[124] Similarly, a recent study showed that subtle humanization of medical patients appears to improve care for these patients. Radiologists evaluating X-rays reported more details to patients and expressed more empathy when a photo of the patient's face accompanied the X-rays.[125] It appears that the inclusion of the photos counteracts the dehumanization of the medical process.

Dehumanization has applications outside traditional social contexts. Anthropomorphism (i.e., perceiving mental and physical capacities that reflect humans in nonhuman entities) is the inverse of dehumanization.[126] Waytz, Epley, and Cacioppo suggest that the inverse of the factors that facilitate dehumanization (e.g., high status, power, and social connection) should promote anthropomorphism. That is, a low status, socially disconnected person without power should be more likely to attribute human qualities to pets or inanimate objects than a high-status, high-power, socially connected person.

Researchers have found that engaging in violent video game play diminishes perceptions of both one's own humanity and the humanity of the players who are targets of the game violence.[127] While the players are dehumanized, the video game characters are often anthropomorphized.

Dehumanization has occurred historically under the pretense of "progress in the name of science". During the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition, human zoos exhibited several natives from independent tribes worldwide, most notably a young Congolese man, Ota Benga. Benga's imprisonment was put on display as a public service showcasing "a degraded and degenerate race". After relocating to New York in 1906, public outcry led to the permanent ban and closure of human zoos in the United States.[128]

In philosophy

Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard explained his stance of anti-dehumanization in his teachings and interpretations of Christian theology. He wrote in his book Works of Love his understanding to be that "to love one's neighbor means equality… your neighbor is every man… he is your neighbor on the basis of equality with you before God; but this equality absolutely every man has, and he has it absolutely."[129]

In art

Spanish romanticism painter Francisco Goya often depicted subjectivity involving the atrocities of war and brutal violence conveying the process of dehumanization. In the romantic period of painting, martyrdom art was most often a means of deifying the oppressed and tormented, and it was common for Goya to depict evil personalities performing these acts; however, he broke convention by dehumanizing these martyr figures: "...one would not know whom the painting depicts, so determinedly has Goya reduced his subjects from martyrs to meat".[130]

See also

- American mutilation of Japanese war dead

- Demonization

- Depersonalization

- Esoteric Nazism

- Life unworthy of life

- Military-age male

- Perceived organizational support

- Perceived psychological contract violation

- Pre-Adamite

- Second-class citizen

- Social defeat

- Ten stages of genocide

- Untermensch

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 Kronfeldner, Maria E., ed (2021). The Routledge handbook of dehumanization. Routledge handbooks in philosophy. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-58815-8.

- ↑ Haslam, Nick (2006). "Dehumanization: An Integrative Review". Personality and Social Psychology Review 10 (3): 252–264. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4. PMID 16859440. https://newclasses.nyu.edu/portal/site/bd325357-284c-4867-9164-8e088b8f7f4f/tool/37d05c72-c02a-426c-9ac9-83e7a9bfab85/discussionForum/message/dfAllMessages. Retrieved 2019-06-22.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Haslam, Nick; Loughnan, Steve (3 January 2014). "Dehumanization and Infrahumanization". Annual Review of Psychology 65 (1): 399–423. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045. PMID 23808915.

- ↑ Spens, Christiana (2014-09-01). "The Theatre of Cruelty: Dehumanization, Objectification & Abu Ghraib" (in en). Contemporary Voices: St Andrews Journal of International Relations 5 (3). doi:10.15664/jtr.946. ISSN 2516-3159.

- ↑ de Ruiter, Adrienne (2024). Dehumanisation in the global migration crisis (1 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-889340-0.

- ↑ Enge, Erik (2015). Dehumanization as the Central Prerequisite for Slavery. GRIN Verlag. p. 3. ISBN 978-3-668-02710-7.

- ↑ Haslam, Nick; Loughnan, Steve (2014). "Dehumanization and infrahumanization". Annual Review of Psychology 65: 399–423. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045. ISSN 1545-2085. PMID 23808915.

- ↑ Bruneau, Emile; Kteily, Nour (2017-01-01). "The enemy as animal: Symmetric dehumanization during asymmetric warfare." (in en). PLOS ONE 12 (7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181422. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28746412. PMC 5528981. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1281422B. https://doaj.org/article/12402d4ab66240a8a6c50c403cf0b8bf.

- ↑ Gordon, Gregory S. (2017) (in en). Atrocity Speech Law: Foundation, Fragmentation, Fruition. Oxford University Press. p. 286. ISBN 978-0-19-061270-2.

- ↑ "Dehumanization is a mental loophole.." (in en-US). 2019-03-17. https://betterblokes.org.nz/2019/03/dehumanization-is-a-mental-loophole/.

- ↑ 11.00 11.01 11.02 11.03 11.04 11.05 11.06 11.07 11.08 11.09 11.10 Nick, Haslam; Steve, Loughnan (3 January 2014). "Dehumanization and Infrahumanization". Annual Review of Psychology 65 (1): 399–423. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045. PMID 23808915.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Nick, Haslam (2024). "Dehumanization and mental health" (in en). World Psychiatry 23 (2): 173–174. doi:10.1002/wps.21186. ISSN 2051-5545. PMID 38727065.

- ↑ Emile, Bruneau; Kteily, Nour (2017-07-26). "The enemy as animal: Symmetric dehumanization during asymmetric warfare" (in en). PLOS ONE 12 (7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181422. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28746412. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1281422B.

- ↑ Jamie L., Goldenberg; Courtney, Emily P.; Felig, Roxanne N. (January 2021). "Supporting the Dehumanization Hypothesis, but Under What Conditions? A Commentary on Over (2021)". Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science 16 (1): 14–21. doi:10.1177/1745691620917659. ISSN 1745-6924. PMID 32348710.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Haslam, Nick (2006). "Dehumanization: An Integrative Review". Personality and Social Psychology Review 10 (3): 252–264. doi:10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_4. PMID 16859440. http://general.utpb.edu/FAC/hughes_j/Haslam%20on%20dehumanization.pdf.

- ↑ Yancey, George (2014). Dehumanizing Christians: Cultural Competition in a Multicultural World. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4128-5267-8.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Nour, Kteily; Alexander, Landry (2022-03-01). "Dehumanization: trends, insights, and challenges" (in English). Trends in Cognitive Sciences 26 (3): 222–240. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2021.12.003. ISSN 1364-6613. PMID 35042655. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1364661321003119.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Adrienne, De Ruiter (2024). Dehumanisation in the global migration crisis (1 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-889340-0.

- ↑ Kteily, Nour S.; Landry, Alexander P. (2022-03-01). "Dehumanization: trends, insights, and challenges" (in English). Trends in Cognitive Sciences 26 (3): 222–240. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2021.12.003. ISSN 1364-6613. PMID 35042655. https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1364661321003119.

- ↑ Daniel Roy Sadek, Habib; Salvatore, Giorgi; Brenda, Curtis (2023-07-04). "Role of the media in promoting the dehumanization of people who use drugs". The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse 49 (4): 371–380. doi:10.1080/00952990.2023.2180383. ISSN 1097-9891. PMID 36995266.

- ↑ Andrighetto, Luca; Baldissarri, Cristina; Lattanzio, Sara; Loughnan, Steve; Volpato, Chiara (2014). "Human-itarian aid? Two forms of dehumanization and willingness to help after natural disasters" (in en). British Journal of Social Psychology 53 (3): 573–584. doi:10.1111/bjso.12066. ISSN 2044-8309. PMID 24588786.

- ↑ Moller, A. C., & Deci, E. L. (2010). "Interpersonal control, dehumanization, and violence: A self-determination theory perspective". Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 13, 41-53. (open access)

- ↑ Haslam, Nick; Kashima, Yoshihisa; Loughnan, Stephen; Shi, Junqi; Suitner, Caterina (2008). "Subhuman, Inhuman, and Superhuman: Contrasting Humans with Nonhumans in Three Cultures". Social Cognition 26 (2): 248–258. doi:10.1521/soco.2008.26.2.248.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Leyens, Jacques-Philippe; Paladino, Paola M.; Rodriguez-Torres, Ramon; Vaes, Jeroen; Demoulin, Stephanie; Rodriguez-Perez, Armando; Gaunt, Ruth (2000). "The Emotional Side of Prejudice: The Attribution of Secondary Emotions to Ingroups and Outgroups". Personality and Social Psychology Review 4 (2): 186–197. doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_06. http://www.armandorodriguez.es/Articulos/archivos/LeyensPaladinoRTorresVaesDemoulinRPerezGaunt2000.pdf.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Bar-Tal, D. (1989). "Delegitimization: The extreme case of stereotyping and prejudice". In D. Bar-Tal, C. Graumann, A. Kruglanski, & W. Stroebe (Eds.), Stereotyping and prejudice: Changing conceptions. New York, NY: Springer.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Opotow, Susan (1990). "Moral Exclusion and Injustice: An Introduction". Journal of Social Issues 46 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1990.tb00268.x.

- ↑ Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and Social Justice. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195112105

- ↑ Kelman, H. C. (1976). "Violence without restraint: Reflections on the dehumanization of victims and victimizers". pp. 282-314 in G. M. Kren & L. H. Rappoport (Eds.), Varieties of Psychohistory. New York: Springer. ISBN 0826119409

- ↑ Fredrickson, Barbara L.; Roberts, Tomi-Ann (1997). "Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women's Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks". Psychology of Women Quarterly 21 (2): 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258181826. Retrieved 2014-11-07.

- ↑ Gervais, Sarah J.; Vescio, Theresa K.; Förster, Jens; Maass, Anne; Suitner, Caterina (2012). "Seeing women as objects: The sexual body part recognition bias". European Journal of Social Psychology 42 (6): 743–753. doi:10.1002/ejsp.1890.

- ↑ Rudman, L. A.; Mescher, K. (2012). "Of Animals and Objects: Men's Implicit Dehumanization of Women and Likelihood of Sexual Aggression". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 38 (6): 734–746. doi:10.1177/0146167212436401. PMID 22374225. http://rutgerssocialcognitionlab.weebly.com/uploads/1/3/9/7/13979590/rudman__mescher_2012._of_animals_and_objects.pdf. Retrieved 2014-11-07.

- ↑ Martha C. Nussbaum (4 February 1999). "Objectification: Section - Seven Ways to Treat A Person as a Thing". Sex and Social Justice. Oxford University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-19-535501-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=7zoaKIolT9oC&pg=PA218.

- ↑ Papadaki, Evangelia (Lina) (2021), Zalta, Edward N., ed., Feminist Perspectives on Objectification (Spring 2021 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2021/entries/feminism-objectification/, retrieved 2022-12-01

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Kronfeldner, Maria E., ed (2021). The Routledge handbook of dehumanization. Routledge handbooks in philosophy. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-58815-8.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Siep Stuurman, "Dehumanization Before The Columbian Exchange." In The Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization, 1st ed., 1:39–51. Routledge, 2021. doi:10.4324/9780429492464-chapter2.

- ↑ Renato G., Mazzolini (2018), Kassell, Lauren; Hopwood, Nick; Flemming, Rebecca, eds., "Colonialism and the Emergence of Racial Theories", Reproduction: Antiquity to the Present Day (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press): pp. 361–374, doi:10.1017/9781107705647.032, ISBN 978-1-107-06802-5, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/reproduction/colonialism-and-the-emergence-of-racial-theories/122DB95AC72DCB6CCDF6C7E034EFEC72, retrieved 2025-05-15

- ↑ Bruneau, Emile; Nour, Kteily (2017-01-01). "The enemy as animal: Symmetric dehumanization during asymmetric warfare." (in en). PLOS ONE 12 (7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181422. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28746412. PMC 5528981. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1281422B. https://doaj.org/article/12402d4ab66240a8a6c50c403cf0b8bf.

- ↑ Luigi Corrias, "Dehumanization by Law 1." In The Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization, 1st ed., 1:201–13. Routledge, 2021. doi:10.4324/9780429492464-chapter13.

- ↑ Emile, Bruneau; Kteily, Nour (2017-07-26). "The enemy as animal: Symmetric dehumanization during asymmetric warfare" (in en). PLOS ONE 12 (7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181422. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28746412. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1281422B.

- ↑ Livingstone Smith, David (2011). Less Than Human: Why We Demean, Enslave, and Exterminate Others. St. Martin's Press. pp. 336. ISBN 978-0-312-53272-7. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780312532727.

- ↑ Smith, David Livingstone; Department of Philosophy, Florida State University (2016). "Paradoxes of Dehumanization". Social Theory and Practice 42 (2): 416–443. doi:10.5840/soctheorpract201642222. ISSN 0037-802X. http://www.pdcnet.org/oom/service?url_ver=Z39.88-2004&rft_val_fmt=&rft.imuse_id=soctheorpract_2016_0042_0002_0416_0443&svc_id=info:www.pdcnet.org/collection. Retrieved 2020-09-10.

- ↑ Luigi Corrias, "Dehumanization by Law 1." In The Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization, 1st ed., 1:201–13. Routledge, 2021. doi:10.4324/9780429492464-chapter13.

- ↑ Maria Rosário Pimentel, "The Justification of Slavery in Modern Natural Law," 33–51. CRC Press | Taylor & Francis, 2022. doi: 10.1201/9780429299070

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Siep Stuurman, "Dehumanization Before The Columbian Exchange." In The Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization, 1st ed., 1:39–51. Routledge, 2021. doi:10.4324/9780429492464-chapter2.

- ↑ Emile, Bruneau; Kteily, Nour (2017-07-26). "The enemy as animal: Symmetric dehumanization during asymmetric warfare" (in en). PLOS ONE 12 (7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181422. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28746412. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1281422B.

- ↑ "Plains Humanities: Wounded Knee Massacre". http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.war.056.

- ↑ "Facebook labels declaration of independence as 'hate speech'". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/jul/05/facebook-declaration-of-independence-hate-speech.

- ↑ Congressional Globe, April 28, 1836, p. 1316.

- ↑ Boime, Albert (2004), A Social History of Modern Art, Volume 2: Art in an Age of Counterrevolution, 1815–1848, (Series: Social History of Modern Art); University of Chicago Press, p. 527.

- ↑ "L. Frank Baum's Editorials on the Sioux Nation". http://www.northern.edu/hastingw/baumedts.htm. Full text of both, with commentary by professor A. Waller Hastings

- ↑ Rickert, Levi (January 16, 2017). "Dr. Martin Luther King Jr: Our Nation was Born in Genocide". https://nativenewsonline.net/currents/dr-martin-luther-king-jr-nation-born-genocide/.

- ↑ "Reflection today: "Our nation was born in genocide when it embraced the doctrin...". Yale University. https://nacc.yalecollege.yale.edu/reflection-today-our-nation-was-born-genocide-when-it-embraced-doctrin.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Bender, Albert (February 13, 2014). "Dr. King spoke out against the genocide of Native Americans". http://www.peoplesworld.org/article/dr-king-spoke-out-against-the-genocide-of-native-americans/.

- ↑ Johansen, Bruce E. (2013), Encyclopedia of the American Indian Movement, ABC-CLIO, "Brando, Marlon" (pp. 60–63); "Littlefeather, Sacheen" (pp. 176–178), ISBN 978-1-4408-0318-5

- ↑ Emile, Bruneau; Kteily, Nour (2017-07-26). "The enemy as animal: Symmetric dehumanization during asymmetric warfare" (in en). PLOS ONE 12 (7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181422. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28746412. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1281422B.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Kronfeldner, Maria E., ed (2021). The Routledge handbook of dehumanization. Routledge handbooks in philosophy. Abingdon, Oxon ; New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-58815-8.

- ↑ Luigi Corrias, "Dehumanization by Law 1." In The Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization, 1st ed., 1:201–13. Routledge, 2021. doi:10.4324/9780429492464-chapter13.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 58.2 58.3 58.4 58.5 Robert Wilson, "Dehumanization, Disability, and Eugenics." In The Routledge Handbook of Dehumanization, 1st ed., 1:173–86. Routledge, 2021. doi:10.4324/9780429492464-chapter11.

- ↑ "From a Speech by Himmler Before Senior SS Officers in Poznan, October 4, 1943". https://www.yadvashem.org/odot_pdf/Microsoft%20Word%20-%204029.pdf.

- ↑ Alexander Landry, Isaias Ghezae, Ramzi Abou-Ismail, Sarah Spooner, River J August, Charlotte Mair, Anya Ragnhildstveit, Wim Van den Noortgate, Michele J Gelfand, and Paul Seli. "The Uniquely Powerful Impact of Explicit, Blatant Dehumanization on Support for Intergroup Violence." Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2025. doi:10.1037/pspi0000492.

- ↑ Jamie L., Goldenberg; Courtney, Emily P.; Felig, Roxanne N. (January 2021). "Supporting the Dehumanization Hypothesis, but Under What Conditions? A Commentary on Over (2021)". Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science 16 (1): 14–21. doi:10.1177/1745691620917659. ISSN 1745-6924. PMID 32348710.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 Joana Ricarte, "Historical Memory, Cultural Violence, and Conflict: The Genealogy of Dehumanization in Israel and Palestine." In Memory, Trauma and Narratives of the Self. United Kingdom: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited, 2024. doi:10.4337/9781035337972.00017.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 63.2 Nick, Haslam; Steve, Loughnan (3 January 2014). "Dehumanization and Infrahumanization". Annual Review of Psychology 65 (1): 399–423. doi:10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045. PMID 23808915.

- ↑ Jay Martin, "The Vicissitudes of Empathy: Reflections on the Israel-Palestine Conflict." Journal of Genocide Research, 2025, 1–17. doi:10.1080/14623528.2025.2458400.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Bruneau, Emile; Nour, Kteily (2017-01-01). "The enemy as animal: Symmetric dehumanization during asymmetric warfare." (in en). PLOS ONE 12 (7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181422. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28746412. PMC 5528981. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1281422B. https://doaj.org/article/12402d4ab66240a8a6c50c403cf0b8bf.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Zouheir Maalej and Aseel Zibin. "Metaphors They Kill by: Dehumanization of Palestinians by Israeli Officials and Sympathizers." International Journal of Arabic-English Studies 25, no. 1 (2025): 201–22. doi:10.33806/ijaes.v25i1.693.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 Emile, Bruneau; Kteily, Nour (2017-07-26). "The enemy as animal: Symmetric dehumanization during asymmetric warfare" (in en). PLOS ONE 12 (7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181422. ISSN 1932-6203. PMID 28746412. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1281422B.

- ↑ Kteily, Nour; Bruneau, Emile; Waytz, Adam; Cotterill, Sarah (November 2015). "The ascent of man: Theoretical and empirical evidence for blatant dehumanization.". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 109 (5): 901–931. doi:10.1037/pspp0000048. PMID 26121523.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Bruneau, Emile; Kteily, Nour (26 July 2017). "The enemy as animal: Symmetric dehumanization during asymmetric warfare". PLOS ONE 12 (7). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0181422. PMID 28746412. Bibcode: 2017PLoSO..1281422B.

- ↑ Kteily, Nour S.. "The " Ascent of (Hu)Man " measure of blatant dehumanization". Current Directions in Psychological Science. https://www.researchgate.net/figure/The-Ascent-of-HuMan-measure-of-blatant-dehumanization-Scores-are-provided-using-a_fig1_315981814.

- ↑ Harel, Tal Orian; Jameson, Jessica Katz; Maoz, Ifat (2020-04-01). "The Normalization of Hatred: Identity, Affective Polarization, and Dehumanization on Facebook in the Context of Intractable Political Conflict" (in EN). Social Media + Society 6 (2). doi:10.1177/2056305120913983. ISSN 2056-3051.

- ↑ McKernan, Bethan (26 January 2024). "Israeli officials accuse international court of justice of antisemitic bias". https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/jan/26/israeli-officials-accuse-international-court-of-justice-of-antisemitic-bias.

- ↑ Eibl-Eibisfeldt, Irenäus (1979). The Biology of Peace and War: Men, Animals and Aggression. New York Viking Press.

- ↑ "The link between hatred, dehumanization, and violence is more complicated than assumed | DIIS" (in en). 2 March 2021. https://www.diis.dk/en/research/the-link-between-hatred-dehumanization-and-violence-is-more-complicated-than-assumed.

- ↑ Resnick, Brian (7 March 2017). "The dark psychology of dehumanization, explained" (in en). https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2017/3/7/14456154/dehumanization-psychology-explained.

- ↑ {{cite journal |last1=Rai |first1=Tage S. |last2=Valdesolo |first2=Piercarlo |last3=Graham |first3=Jesse |title=Dehumanization increases instrumental violence, but not moral violence |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |date=8 August 2017 |volume=114 |issue=32 |pages=8511–8516 |doi=10.1073/pnas.1705238114

External links

|