Social:Eastern Baltic languages

| Eastern Baltic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | In Northern Europe, Baltic region |

| Linguistic classification | Indo-European

|

| Subdivisions | |

| ISO 639-5 | bat |

| Linguasphere | 54= |

| Glottolog | east2280[1] |

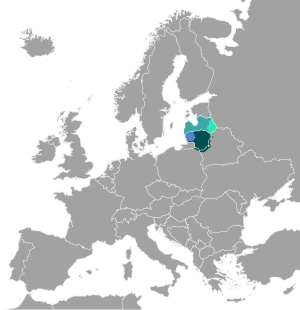

Extent of Baltic languages in present day Europe with languages traditionally considered to be dialects mentioned in Italics Eastern Baltic languages | |

The Eastern Baltic languages are a group of languages that along with the extinct Western Baltic languages belong to the Baltic branch of the Indo-European language family. The Eastern Baltic branch has only two living languages—Latvian and Lithuanian.[2] In some cases, Latgalian and Samogitian are also considered to be separate languages but they are generally treated as dialects. It also includes now-extinct Selonian, Semigallian, and possibly Old Curonian.[3]

Lithuanian is the most-spoken Eastern Baltic language, with more than 3 million speakers worldwide, followed by Latvian, with 1.75 million native speakers.[4][5]

History

Origins and characteristics

Originally, East Baltic was presumably native to the north of Eastern Europe, which included modern Latvia, Lithuania, northern parts of current European Russia and Belarus . Dnieper Balts lived in the current territory of Moscow, which was the furthest undisputed eastern territory inhabited by the Baltic people.

Traditionally, it is believed that Western and Eastern Baltic people had already possessed certain unique traits that separated them in the middle of the last millennium BC and began to permanently split between 5th and 3rd century BC.[6] During this time, Western and Eastern Balts adopted different traditions and customs. They had separate ceramics and housebuilding traditions. In addition, both groups had their own burial customs: unlike their Western counterparts, it is believed that Eastern Balts would burn the remains of the dead and scatter the ashes on the ground or nearby rivers and lakes. It is also known that Eastern Balts were much more susceptible to the cultural influences coming from their Baltic Finnic neighbours in the northeast.[6]

The Eastern Baltic languages are less archaic than their Western counterparts with Latvian being the most innovative Baltic language. In part due to the influence of Baltic Finnic languages on their development, such as in the case of stress retraction. The extinct languages of the Eastern family group are poorly understood as they are practically unattested.[7] However, from the analysis of hydronyms and retained loanwords, it is known that Selonian and Old Curonian languages possessed the retention of nasal vowels *an, *en, *in, *un. It is noted that Selonian, Semigallian and Old Latgalian palatalised soft velars *k, *g into *c, *dz while also depalatalising the sounds *š, *ž into *s, *z respectively. This is observed in hydronyms and oeconyms (e.g. Zirnajai, Zalvas, Zarasai) as well as loanwords preserved in Lithuanian and Latvian dialects.[8] It is believed that Semigallian possessed an uninflected pronoun, which was the equivalent to the Lithuanian savo (e.g. Sem. Savazirgi, Lith. savo žirgai, meaning 'one's horses').[9] Eastern Baltic would in many cases turn the diphthong *ei into a monophthong, pronounced like the contemporary Lithuanian letter ė ( like jē in Latvian). This would further develop in Lithuanian and Latvian to become the present diphthong *ie (e.g. Lith. dievas, Lat. dievs 'god').[7] This innovation becomes obvious when comparing ablauted words of the same root, where o-grade words do not reflect this change (e.g Lat. ciems, Lit. kaimas 'village'). Unlike their Western counterparts, Eastern Baltic languages usually tend to keep their short vowels *o and *a separately (e. g., Lith. duoti, Lat. duot 'give' as opposed to Lith. motina, Lat. māte 'mother').[10]

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Eastern Baltic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/east2280.

- ↑ Gimbutas, Marija (1963). The Balts. Ancient peoples and places 33. London: Thames and Hudson. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ↑ Östen Dahl (ed.) 2001, The Circum-Baltic Languages: Typology and Contact, vol. 1

- ↑ Lithuanian language at Ethnologue (19th ed., 2016)

- ↑ Latvian at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) Standard Latvian language at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) Latgalian language at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Zinkevičius, Zigmas, Luchtanas, Aleksiejus, Česnys, Gintautas (2006). Apie skirtumus tarp rytų ir vakarų baltų [About the Differences Between Eastern and Western Balts] (in Lithuanian).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Rytų ir vakarų baltai. Du baltų tarimų junginiai [Eastern and Western Balts. Two Compounds of Baltic Spelling] (in Lithuanian). Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas.

- ↑ Zinkevičius, Zigmas (1984). Lietuvių kalbos istorija [History of Lithuanian Language] (in Lithuanian). I. Vilnius: Mokslas. p. 361. ISBN 5-420-00102-0.

- ↑ Dini, P.U. (2000). Baltų kalbos. Lyginamoji istorija [Baltic Languages. Comparative History] (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos institutas. p. 235. ISBN 5-420-01444-0.

- ↑ Schmalstieg, W. R. (1974). An Old Prussian Grammar: The Phonology and Morphology of the Three Catechisms. The Pennsylvania State University, University Park and London, p. 17.