Social:February 28 incident

On February 28, 1947, the masses went to the Monopoly Bureau Taipei Branch to protest, and the inventories of matches, cigarettes and other items in the Monopoly Bureau Taipei Branch were piled up and burned. | |

| Date | February 27 - May 16, 1947 |

|---|---|

| Location | Taiwan Province, China |

| Outcome |

|

| Deaths | Between 18,000 and 28,000 people[1][2] |

The February 28 incident, also rendered as the February 28 massacre,[3][4] the 228 incident,[5] or the 228 massacre[5] was an anti-government uprising in Taiwan that was violently suppressed by the Kuomintang (KMT)–led nationalist government of the Republic of China (ROC). Directed by provincial governor Chen Yi and president Chiang Kai-shek, thousands of civilians were killed beginning on February 28, 1947.[6] The number of deaths from the incident and massacre was estimated to be between 18,000 and 28,000.[1][7] The incident is one of the most important events in Taiwan's modern history and was a critical impetus for the Taiwan independence movement.[8]

In 1945, following the surrender of Japan at the end of World War II, the Allies handed administrative control of Taiwan to the Republic of China (ROC), thus ending 50 years of Japanese colonial rule. Local inhabitants became resentful of what they saw as highhanded and frequently corrupt conduct on the part of the Kuomintang (KMT) authorities, including arbitrary seizure of private property, economic mismanagement, and exclusion from political participation. The flashpoint came on February 27, 1947, in Taipei, when agents of the State Monopoly Bureau struck a Taiwanese widow suspected of selling contraband cigarettes. An officer then fired into a crowd of angry bystanders, striking one man who died the next day.[9] Soldiers fired upon demonstrators the next day, after which a radio station was seized by protesters and news of the revolt was broadcast to the entire island. As the uprising spread, the KMT–installed governor Chen Yi called for military reinforcements, and the uprising was violently put down by the National Revolutionary Army. 2 years later for the following 38 years, the island was placed under martial law in a period known as the White Terror.[9]

During the White Terror, the KMT persecuted perceived political dissidents, and the incident was considered too taboo to be discussed. President Lee Teng-hui became the first president to discuss the incident publicly on its anniversary in 1995. The event is now openly discussed and details of the event have become the subject of government and academic investigation. February 28 is now an official public holiday called Peace Memorial Day, on which the president of Taiwan gathers with other officials to ring a commemorative bell in memory of the victims. Monuments and memorial parks to the victims of the February 28 incident have been erected in a number of Taiwanese cities. In particular, Taipei's former Taipei New Park was renamed 228 Peace Memorial Park, and the National 228 Memorial Museum was opened on February 28, 1997. The Kaohsiung Museum of History also has a permanent exhibit detailing the events of the incident in Kaohsiung.[10][11] In 2019, the Transitional Justice Commission exonerated those who were convicted in the aftermath.[12]

| February 28 incident |

|---|

Background

During the 50 years of Japanese rule in Taiwan (1895–1945), Taiwan experienced economic development and an increased standard of living, serving as a supply base for the Japanese main islands.[13] After World War II, Taiwan was placed under the administrative control of the Republic of China to provide stability until a permanent arrangement could be made. Chen Yi, the governor-general of Taiwan, arrived on October 24, 1945, and received the last Japanese governor, Ando Rikichi, who signed the document of surrender on the next day. Chen Yi then proclaimed the day as Retrocession Day to make Taiwan part of the Republic of China.

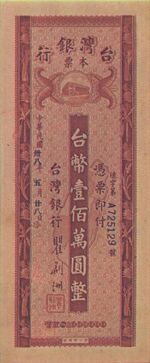

Taiwanese perceptions of the Japanese rule were more positive than perceptions in other parts of East and Southeast Asia that came under Japanese imperialism.[14] Despite this, the Kuomintang troops from Mainland China were initially welcomed by the Taiwanese. Their harsh conduct and the KMT maladministration quickly led to Taiwanese discontent during the immediate postwar period. As governor-general, Chen Yi took over and sustained the Japanese system of state monopolies in tobacco, sugar, camphor, tea, paper, chemicals, petroleum refining, mining, and cement, the same way the Nationalists treated people in other former Japanese-controlled areas (earning Chen Yi the nickname "robber" (劫收)).[15] He confiscated some 500 Japanese-owned factories and mines, and homes of former Japanese residents. Economic mismanagement led to a large black market, runaway inflation and food shortages. Many commodities were compulsorily bought cheaply by the KMT administration and shipped to Mainland China to meet the Civil War shortages where they were sold at very high profit furthering the general shortage of goods in Taiwan. The price of rice rose to 100 times its original value between the time the Nationalists took over to the spring of 1946, increasing to nearly four times the price in Shanghai. It inflated further to 400 times the original price by January 1947.[16] Carpetbaggers from Mainland China dominated nearly all industry, as well as political and judicial offices, displacing the Taiwanese who were formerly employed. Many of the ROC garrison troops were highly undisciplined, looting, stealing and contributing to the overall breakdown of infrastructure and public services.[17] Because the Taiwanese elites had met with some success with self-government under Japanese rule, they had expected the same system from the incoming ruling Chinese Nationalist Government. However, the Chinese Nationalists opted for a different route, aiming for the centralization of government powers and a reduction in local authority. The KMT's nation-building efforts followed this ideology because of unpleasant experiences with the centrifugal forces during the Warlord Era in 1916–1928 that had torn the government in China. Mainland Communists were even preparing to bring down the government like the Ili Rebellion.[18] The different goals of the Nationalists and the Taiwanese, coupled with cultural and language misunderstandings served to further inflame tensions on both sides.

Uprising and crackdown

On the evening of February 27, 1947, a Tobacco Monopoly Bureau enforcement team in Taipei went to the district of Taiheichō (zh) (太平町), Twatutia (Dadaocheng in Mandarin), where they confiscated contraband cigarettes from a 40-year-old widow named Lin Jiang-mai (林江邁) at the Tianma Tea House. When she demanded their return, one of the men struck her in the head with the butt of his gun,[9] prompting the surrounding Taiwanese crowd to challenge the Tobacco Monopoly agents. As they fled, one agent shot his gun into the crowd, hitting a bystander who died the next day. The crowd, which had already been harboring feelings of frustration from unemployment, inflation, and corruption toward the Nationalist government, reached its breaking point. The crowd protested to both the police and the gendarmes but were mostly ignored.[19]

Protesters gathered the next morning around Taipei, calling for the arrest and trial of the agents involved in the previous day's shooting, and eventually made their way to the Governor General's Office, where security forces tried to disperse the crowd. Soldiers opened fire into the crowd, killing at least three people.[20] Formosans took over the administration of the town and military bases on March 4 and forced their way into local radio station to broadcast news of the incident and calling for people to revolt, causing uprisings to erupt throughout the island.[21][22] By evening, martial law had been declared, and curfews were enforced by the arrest or shooting of anyone who violated curfew.

For several weeks after the February 28 incident, the Taiwanese civilians controlled much of Taiwan. The initial riots were spontaneous and sometimes violent, with mainland Chinese receiving beatings from and being killed by Taiwanese.[22] Within a few days, the Taiwanese were generally coordinated and organized, and public order in Taiwanese-held areas was upheld by volunteer civilians organized by students, and unemployed former Japanese army soldiers. Local leaders formed Settlement Committees (or Resolution Committees), which presented the government with a list of 32 Demands for reform of the provincial administration. They demanded, among other things, greater autonomy, free elections, the surrender of the ROC Army to the Settlement Committee, and an end to government corruption.[22] Motivations among the various Taiwanese groups varied; some demanded greater autonomy within the ROC, while others wanted UN trusteeship or full independence.[23] The Taiwanese also demanded representation in the forthcoming peace treaty negotiations with Japan, hoping to secure a plebiscite to determine the island's political future.

Outside of Taipei, there were examples of the formation of local militas such as the 27 Brigade near Taichung. In Chiayi, the mayor's residence was set on fire and local militias fought with the military police.[24]

The Nationalist Government, under Chen Yi, stalled for time while it waited for reinforcements from Fujian. Upon their arrival on March 8, the ROC troops launched a crackdown. The New York Times reported, "An American who had just arrived in China from Taihoku said that troops from the mainland China arrived there on March 7 and indulged in three days of indiscriminate killing and looting. For a time everyone seen on the streets was shot at, homes were broken into and occupants killed. In the poorer sections the streets were said to have been littered with dead. There were instances of beheadings and mutilation of bodies, and women were raped, the American said."[25]

By the end of March, Chen Yi had ordered the imprisonment or execution of the leading Taiwanese organizers he could identify. His troops reportedly executed, according to a Taiwanese delegation in Nanjing, between 3,000 and 4,000 people throughout the island, though the exact number is still undetermined.[26] Detailed records kept by the KMT have been reported as "lost". Some of the killings were random, while others were systematic. Taiwanese elites were among those targeted, and many of the Taiwanese who had formed self-governing groups during the reign of the Japanese were also victims of the February 28 incident. A disproportionate number of the victims were Taiwanese high school students. Many had recently served in the Imperial Japanese Army, having volunteered to serve to maintain order.[22]

Some Taiwan political organizations participated in the uprising, for example Taiwan Democratic Self-Government League, was announced "communist" and illegal. Many members were arrested and executed. Some of these organizations had to move to Hong Kong.[27]

By late March 1947, the central executive committee of the KMT recommended that Chen Yi be dismissed as governor-general over the "merciless brutality" he had shown in suppressing the rebellion.[28] In June 1948, he was appointed provincial chairman of Zhejiang province. In January 1949, he attempted to defect to the Chinese Communist Party, but, informed of the attempt, Chiang Kai-shek immediately relieved Chen of his chairmanship. In April 1950, Chen Yi was escorted to Taiwan and later imprisoned in Keelung. In May 1950, Chiang Kai-shek ordered the Taiwan military court to sentence Chen Yi to death for espionage. On June 18, he was executed at Machangding, Taipei.[29] The government hoped that the execution of Governor Chen Yi and financial compensation for the victims had quelled resentment.[citation needed]

Legacy

During the February 28 incident, Taiwanese leaders established Resolution Committees in various cities (with a central committee in Taipei) and demanded greater political autonomy. Negotiations with the ROC ended when troops arrived in early March. The subsequent feelings of betrayal felt towards the government and China are widely believed to have catalyzed today's Taiwan independence movement post-democratization.[22] The initial February 28 purge was followed 2 years later by 38 years of martial law, commonly referred to as the "White Terror", which lasted until the end of 1987, during which over 100,000 people were imprisoned for political reasons[30] of which over 1,000 were executed.[31] During this time, discussion of the incident was taboo.[32]

In the 1970s, the 228 Justice and Peace Movement was initiated by several citizens' groups to ask for a reversal of this policy,[citation needed] and, in 1992, the Executive Yuan promulgated the "February 28 Incident Research Report".[33] Then-president and KMT-chairman Lee Teng-hui, who had participated in the incident and was arrested as an instigator and a Communist sympathizer, made a formal apology on behalf of the government in 1995 and declared February 28 a day to commemorate the victims.[34] Among other memorials erected, Taipei New Park was renamed 228 Memorial Park.

In 1990, the ROC Executive Yuan set up a task force to investigate the February 28 incident. The "Report of the 228 Incident" (二二八事件研究報告) was published in 1992, and a memorial was set up in 1995 at the 228 Peace Park in Taipei. In October 1995, the state-funded Memorial Foundation of 228 (二二八事件紀念基金會) was established to distribute compensation and award rehabilitation certificates to February 28 incident victims in order to restore their reputation.[35] Family members of dead and missing victims are eligible for NT$6 million (approximately US$190,077).[36] The foundation reviewed 2,885 applications, most of which were accepted. Of these, 686 involved deaths, 181 involved missing persons, and 1,459 involved imprisonment.[37] Many descendants of victims remain unaware that their family members were victims, while many of the families of victims from Mainland China did not know the details of their relatives' mistreatment during the riot.[citation needed] Those who have received compensation more than two times are demanding trials of the still-living soldiers and officials who were responsible for the summary executions and deaths of their loved ones.[citation needed]

On February 28, 2004, thousands of Taiwanese participated in the 228 Hand-in-Hand Rally. They formed a 500-kilometer (310 mi) long human chain from Taiwan's northernmost city to its southern tip to commemorate the incident, to call for peace, and to protest the People's Republic of China's deployment of missiles aimed at Taiwan along the coast of Taiwan Strait.[38]

In 2006, the Research Report on Responsibility for the 228 Massacre (二二八事件責任歸屬研究報告) was released after several years of research. The 2006 report was not intended to overlap with the prior (1992) 228 Massacre Research Report commissioned by the Executive Yuan. Chiang Kai-shek is specifically named as bearing the largest responsibility in the 2006 report.

We think that Chiang Kai-Shek, president of the Nationalist government, should bear the biggest responsibility for the 228 Massacre. Reasons being that he not only was oblivious to warning cautioned by the Control Yuan prior to the Massacre, he was also partial to Chen Yi afterward. None of the provincial military and political officials in Taiwan were punished because of the Massacre. Further more, he deployed forces right after the Massacre, as written in a letter by Chen Yi to Chiang Kai-Shek dated March 13: “If not for Your Excellency to mobilize troop rapidly, one could not imagine how far this massacre will lead to.” Chiang Kai-Shek, despite all information he gathered from the party, government, army, intelligence, and representative of Taiwanese groups, still chose to send troops right away; he summoned commander of the 21st division Liu Yu-Cing and gave him 600 pistols simultaneously, all of which deteriorated the situation.[39]

Art

A number of artists in Taiwan have addressed the subject of the February 28 incident since the taboo was lifted on the subject in the early 1990s.[40] The incident has been the subject of music by Fan-Long Ko and Tyzen Hsiao and a number of literary works.

Film

Hou Hsiao-hsien's A City of Sadness, the first movie dealing with the events, won the Golden Lion at the 1989 Venice Film Festival.[41] The 2009 thriller Formosa Betrayed also relates the incident as part of the motivation behind Taiwan independence activist characters.

Literature

Jennifer Chow's 2013 novel The 228 Legacy brings to light the emotional ramifications for those who lived through the events yet suppressed their knowledge out of fear. It focuses on how there was such an impact that it permeated throughout multiple generations within the same family.[42] Shawna Yang Ryan's 2016 novel Green Island tells the story of the incident as it affects three generations of a Taiwanese family, [43] while Julie Wu's novel The Third Son (2013) describes the event and its aftermath from the viewpoint of a Taiwanese boy.[44]

Music

Taiwanese metal band Chthonic's album Mirror of Retribution makes several lyrical references to the February 28 incident.

See also

- Formosa Betrayed (1965 book)

- History of Taiwan

- History of the Republic of China

- List of massacres in Taiwan

- List of massacres in China

- The First 228 Peace Memorial Monument

- 228 Hand-in-Hand Rally (in 2004)

- Political status of Taiwan

- White Terror (Taiwan)

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948)

- KMT retreat to Taiwan in 1949

- 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre

- 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Forsythe, Michael (July 14, 2015). "Taiwan Turns Light on 1947 Slaughter by Chiang Kai-shek's Troops". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/15/world/asia/taiwan-turns-light-on-1947-slaughter-by-chiang-kai-sheks-troops.html. "To somber cello music that evokes 'Schindler's List,' displays memorialize the lives lost, including much of the island's elite: painters, lawyers, professors, and doctors. In 1992, an official commission estimated that 18,000 to 28,000 people had been killed."

- ↑ Kristof, Nicholas D. (April 3, 1992). "Taipei Journal; The Horror of 2-28: Taiwan Rips Open the Past". https://www.nytimes.com/1992/04/03/world/taipei-journal-the-horror-of-2-28-taiwan-rips-open-the-past.html.

- ↑ Wu, Naiteh (July 2005). "Transition without Justice, or Justice without History: Transitional Justice in Taiwan". Taiwan Journal of Democracy (1): 10. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. https://web.archive.org/web/20210225145304/https://www.ios.sinica.edu.tw/people/personal/wnd/TransitionWithoutJusticeOrJusticeWithoutHistory.pdf. "The memory of the February 28 massacre, although politically taboo during the KMT's authoritarian rule".

- ↑ "Taiwan's hidden massacre. A new generation is breaking the silence". The Washington Post. March 1, 2017. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/02/28/for-decades-no-one-spoke-of-taiwans-hidden-massacre-a-new-generation-is-breaking-the-silence/?postshare=3041488336764121. "realization that his grandfather had been one of the tens of thousands of victims targeted and murdered in Taiwan's 'February 28 Massacres.'"

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Shattuck, Thomas J. (February 27, 2017). "Taiwan's White Terror: Remembering the 228 Incident". Foreign Policy Research Institute. https://www.fpri.org/article/2017/02/taiwans-white-terror-remembering-228-incident/. "In Taiwan, the period immediately following the 228 Incident is known as the 'White Terror' ... . Just blocks away from the Presidential Palace in Taipei is a museum and park memorializing the victims of the 228 Massacre"

- ↑ "China's other massacre". June 4, 2019. https://justinward.medium.com/chinas-other-massacre-a0f79398e034.

- ↑ Kristof, Nicholas D. (April 3, 1992). "Taipei Journal; The Horror of 2-28: Taiwan Rips Open the Past". https://www.nytimes.com/1992/04/03/world/taipei-journal-the-horror-of-2-28-taiwan-rips-open-the-past.html.

- ↑ Fleischauer, Stefan (November 1, 2007). "The 228 Incident and the Taiwan Independence Movement's Construction of a Taiwanese Identity". China Information 21 (3): 373–401. doi:10.1177/0920203X07083320.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Chou, Wan-yao (2015). A New Illustrated History of Taiwan. Taipei: SMC Publishing Inc.. p. 317. ISBN 978-957-638-784-5.

- ↑ Ko, Shu-ling; Chang, Rich; Chao, Vincent Y. (March 1, 2011). "National 228 museum opens in Taipei". Taipei Times: p. 1. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2011/03/01/2003497056.

- ↑ Chen, Ketty W. (February 28, 2013). "Remembering Taiwan's Tragic Past". Taipei Times: p. 12. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2013/02/28/2003555884.

- ↑ Lin, Sean (October 6, 2018). "Commission exonerates 1,270 people". Taipei Times (Taipei). http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2018/10/06/2003701820.

- ↑ Wu, J.R. (October 25, 2015). "Taiwan president says should remember good things Japan did". Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-taiwan-china/taiwan-president-says-should-remember-good-things-japan-did-idUSKCN0SJ03Y20151025. "Unlike in China or Korea, many Taiwanese have a broadly more positive view of Japan than people in China or Korea, saying that Japan's rule brought progress to an undeveloped, largely agricultural island."

- ↑ Abramson, Gunnar (2004). "Comparative Colonialisms: Variations in Japanese Colonial Policy in Taiwan and Korea, 1895 ‐ 1945". PSU McNair Scholars Online Journal 1 (1): 11–37. doi:10.15760/mcnair.2005.11.

- ↑ 大「劫收」与上海民营工业. 檔案與史學. March 1, 1998. http://www.ixueshu.com/document/9418c49ad68ded70.html.

- ↑ "Formosa After the War". Reflection on the 228 Event—The first gunshot. 2003. http://www.2003hr.net/English/cul_xb0101.php.

- ↑ "Foreign News: This Is the Shame". Time (magazine). June 10, 1946. http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,792979,00.html.

- ↑ Cai, Xi-bin (January 11, 2010). The Taiwan province working committee organization of the CCP (1946~1950) in Taipei city. National Tamkang University. http://tkuir.lib.tku.edu.tw:8080/dspace/handle/987654321/34228.

- ↑ (in zh)民報社 (Taiwan Ministry of Culture:National Repository of Cultural Heritage), February 28, 1947, http://nrch.cca.gov.tw/ccahome/search/search_meta.jsp?xml_id=0001716464&dofile=getImage.jsp?d=1241951145639&id=0001648015&filename=cca100003-np-mingpo19470228-03-i.jpg

- ↑ "Seizing-cigarettes incident". Reflection on the 228 Event—The first gunshot. 2003. http://www.2003hr.net/English/cul_xb0102.php.

- ↑ Durdin, Peggy (May 24, 1947). "Terror in Taiwan". The Nation. http://www.taiwandc.org/hst-1947.htm. Retrieved April 22, 2006.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 Smith, Craig A (2008). "Taiwan's 228 Incident and the Politics of Placing Blame". Past Imperfect (University of Alberta) 14: 143–163. ISSN 1711-053X. https://ejournals.library.ualberta.ca/index.php/pi/article/view/4228. Retrieved November 13, 2014.

- ↑ Durdin, Tillman (March 30, 1947). "Formosans' Plea For Red Aid Seen". The New York Times. http://228.lomaji.com/news/033047.html.

- ↑ Yang, Bi-chuan (February 25, 2017). "The 228 Massacre in Chiayi: "The Airport and Train Station Were Washed with Blood". The Reporter (報導者). https://www.taiwangazette.org/news/2019/3/5/the-228-massacre-in-chiayi-the-airport-and-train-station-were-washed-with-blood.

- ↑ Durdin, Tillman (March 29, 1947). "Formosa killings are put at 10,000". The New York Times. http://www.taiwandc.org/hst-1947.htm.

- ↑ "DPP questions former Premier Hau's 228 victim figures". The China Post (Taipei). February 29, 2012. http://www.chinapost.com.tw/taiwan/national/national-news/2012/02/29/333129/DPP-questions.htm.

- ↑ Wang, Xiaobo (February 2004). Taiwan Democratic Self-Government League and the February 28 Incident. Taipei: Straits Academic Press.[page needed]

- ↑ "Chiang to Formosa?". Argus-Press (Owosso, Michigan). January 14, 1949. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1978&dat=19490114&id=IpEnAAAAIBAJ&pg=6456,1329226.

- ↑ "Formosa Chief Executed As Traitor". Schenectady Gazette. AP. June 18, 1950. https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1917&dat=19500619&id=yaE0AAAAIBAJ&pg=820,2825535.

- ↑ Bird, Thomas (August 1, 2019). "Taiwan's brutal White Terror period revisited on Green Island: confronting demons inside a former prison". South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/long-reads/article/3020894/taiwans-brutal-white-terror-period-revisited.

- ↑ Mozur, Paul (February 3, 2016). "Taiwan Families Receive Goodbye Letters Decades After Executions". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/02/04/world/asia/taiwan-white-terror-executions.html.

- ↑ Horton, Chris (February 26, 2017). "Taiwan Commemorates a Violent Nationalist Episode, 70 Years Later". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/26/world/asia/taiwan-1947-kuomintang.html.

- ↑ Kristof, Nicholas D. (April 3, 1992). "Taipei Journal; The Horror of 2–28: Taiwan Rips Open the Past". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/1992/04/03/world/taipei-journal-the-horror-of-2-28-taiwan-rips-open-the-past.html.

- ↑ Mo, Yan-chih (February 28, 2006). "Remembering 228: Ghosts of the past are yet to be laid to rest". Taipei Times: p. 4. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/print/2006/02/28/2003295019.

- ↑ http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2017/05/29/2003671507; https://228.org.tw/en/operation.html

- ↑ "Japanese 228 victim's son awarded compensation". Taipei Times. February 18, 2016. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2016/02/18/2003639617.

- ↑ "賠償金申請相關事宜|財團法人二二八事件紀念基金會.二二八國家紀念館". https://228.org.tw/pages.php?sn=14.

- ↑ Chang, Yun-ping (2004-02-29). "Two million rally for peace". Taipei Times. https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2004/02/29/2003100533.

- ↑ Chen, Yi-shen (February 2005). "Research Report on Responsibility for the 228 Massacre, Chapter II: Responsibility on the part of the decision-makers in Nanjing". The 228 Memorial Foundation. http://www.228.org.tw/ResponsibilityReport/eng/06.htm.

- ↑ "228 Massacre, 60th Commemoration". http://www.taiwandc.org/228-60.htm.

- ↑ "A City of Sadness". October 21, 1989. https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0096908/awards.

- ↑ Bloom, Dan (August 19, 2013). "US author probes 'legacy' of the 228 Incident in novel". Taipei Times: p. 3. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2013/08/19/2003570059.

- ↑ "Green Island by Shawna Yang Ryan - PenguinRandomHouse.com". http://knopfdoubleday.com/book/246332/green-island/.

- ↑ "The Third Son". https://www.workman.com/products/the-third-son-2.

Bibliography

- Kerr, George H.; Stuart, John Leighton (April 21, 1947). Memorandum on the Situation in Taiwan (Report). American Embassy, Nanking, China. Telegram No. 689. reprinted in United States relations with China, with special reference to the period 1944–1949, based on the files of the Department of State. Far Eastern Series. Compiled by Dean Acheson. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off.. August 1949. pp. 923–938. OCLC 664471448.

- Kerr, George H. (1965). Formosa Betrayed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Lai, Tse-han; Myers, Ramon Hawley; Wei, Wou (1991). A Tragic Beginning: The Taiwan Uprising of February 28, 1947. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804718295.

- Shackleton, Allan J. (1998). Formosa Calling: An Eyewitness Account of Conditions in Taiwan during the February 28th, 1947 Incident. Upland, California: Taiwan Publishing Company. OCLC 419279752. http://homepage.usask.ca/~llr130/taiwanlibrary/formosacalling/formosaframes.htm. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- Wakabayashi, Masahiro (2003). "4: Overcoming the Difficult Past; Rectification of the 2–28 Incident and the Politics of Reconciliation in Taiwan". in Funabashi, Yōichi. Reconciliation in the Asia-Pacific. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press. pp. 91–109. ISBN 9781929223473. OCLC 51755853.

External links

| Library resources about February 28 incident |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to 228 Incident of Taiwan, 1947. |

- "Taipei 228 Memorial Museum (臺北228紀念館)". Taiwan Ministry of Culture. http://www.culture.tw/index.php?option=com_sobi2&sobi2Task=sobi2Details&sobi2Id=148&Itemid=175.

- Hong, Keelung (February 28, 2003). My Search for 2–28 (Speech). Berkeley, California. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- "The 228 Massacre, As Documented in the US Media". 2001. http://228.lomaji.com/.

- "Reflection on the 228 Event". Taiwan Human Rights InfoNet. 2003. http://www.2003hr.net/English/cul_xb00.php.

- "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in zh). 2011. http://www.228.org.tw/. - Chu, Bevin (February 25, 2000). "Taiwan Independence and the 2–28 Incident". The Strait Scoop. http://www.antiwar.com/chu/c022500.html.

- "Taiwan Yearbook 2006: The ROC on Taiwan — February 28 Incident". http://www.gio.gov.tw/taiwan-website/5-gp/yearbook/03History.htm#ROC.

- "Declaration of Formosan Civil Government 福爾摩沙平民政府宣言". 2009. http://tw01.org/profiles/blogs/declaration-of-formosan-civil.

- (in zh)Liberty Times (Taipei). February 28, 2007. http://www.libertytimes.com.tw/2007/new/feb/28/today-s1.htm.

- "Editorial: Historical record is key to justice". Taipei Times: p. 8. February 28, 2007. http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/archives/2007/02/28/2003350397.

- The 228 Incident and Taiwan's Transitional Justice – The Diplomat

- Japanese 228 victim's son awarded compensation – Taipei Times

- Tsai vows to investigate 228 Incident – Taipei Times

- Family of Korean killed in Taiwan's '228 Incident' in 1947 to get compensation – The Japan Times

- KMT slows transitional justice: Koo – Taipei Times

- Forum underlines importance of 228 education – Taipei Times

- Chiang Kai-shek removal backed – Taipei Times

- 228 evidence indicts Chiang: academic – Taipei Times

- Document unearthed shows double-dealing of Chiang behind 228 Incident – Taiwan News