Social:Geographical indication

A geographical indication (GI) is a name or sign used on products which corresponds to a specific geographical location or origin (e.g., a town, region, or country). The use of a geographical indication, as an indication of the product's source, acts as a certification that the product possesses certain qualities, is made according to traditional methods, or enjoys a good reputation due to its geographical origin.

Appellation d'origine contrôlée ('Appellation of origin') is a sub-type of geographical indication where quality, method, and reputation of a product originate from a strictly defined area specified in its intellectual property right registration.

History

Governments have protected trade names and trademarks of food products identified with a particular region since at least the end of the 19th century, using laws against false trade descriptions or passing off, which generally protects against suggestions that a product has a certain origin, quality, or association when it does not. In such cases, the limitation on competitive freedoms which results from the grant of a monopoly of use over a geographical indication is justified by governments either by consumer protection benefits or by producer protection benefits.

One of the first GI systems is the one used in France from the early part of the 20th century known as appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC). Items that meet geographical origin and quality standards may be endorsed with a government-issued stamp which acts as official certification of the origins and standards of the product. Examples of products that have such "appellations of origin" include Gruyère cheese (from Switzerland) and many French wines.

Geographical indications have long been associated with the concept of terroir and with Europe as an entity, where there is a tradition of associating certain food products with particular regions. Under European Union Law, the protected designation of origin framework which came into effect in 1992 regulates the following systems of geographical indications: "Protected designation of origin" (PDO), "protected geographical indication" (PGI), and Traditional Specialities Guaranteed" (TSG).[1]

Legal effect

Geographical Indications protection is granted through the TRIPS Agreement.[1] Protection afforded to geographical indications by law is arguably twofold:

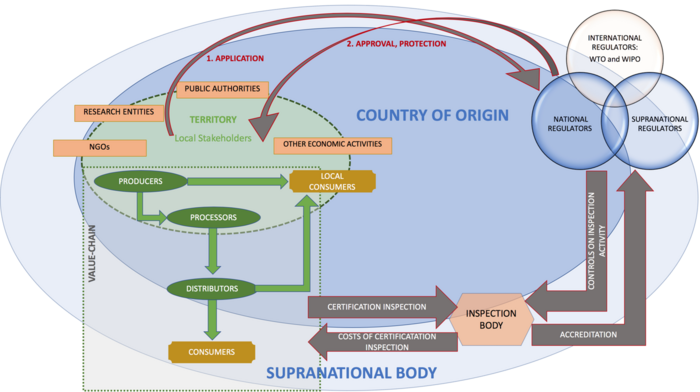

- On one hand it is granted through sui generis law (public law), for example in the European Union. In other words, GI protection should apply through ex officio protection, where authorities may support and get involved in the making of GI collective dimensions together with their corresponding GI regulatory council, where ongoing discourse with the government is implied for effective inspection and quality control.

- On the other hand, it is granted through common law (private law). In other words, it is similar to the protection afforded to trademarks, as it can be registered through collective trademarks and also through certification marks, for example in the United States of America.

GI protection systems restrict the use of the GIs for the purpose of identifying a particular type of product, unless the product and/or its constituent materials and/or its fabrication method originate from a particular area and/or meet certain standards. Sometimes these laws also stipulate that the product must meet certain quality tests that are administered by an association that owns the exclusive right to license or allow the use of the indication. GIs are recognised through either public or private law: depending on the GI protection system applied among the different WTO state members, either through common law or through sui generis law. Thus the conflicts between prior trademark registration and GIs is a subject of international debate that is yet to be resolved; this is what makes the GI system rather positional[clarification needed] in terms of international trade negotiations. These conflicts are generally resolved through three intellectual property protection approaches: first in time[clarification needed] –first in right approach, coexistence approach, GI superiority approach.

Arguably trademarks are seen as a valuable asset in terms of private business and their economic assets, while GIs are strongly connected to socio-economic development, along the lines of sustainability in countries rich in traditional knowledge.[clarification needed] The geographical origin of a product can create value to producers by:

- communicating to consumers the product's characteristics, which derive from the climate, soil and other natural conditions in its particular area;

- promoting the conservation of local traditional production process; and

- protecting and adding value to the cultural identity of local communities.

The consumer-benefit purpose of the protection rights granted to the beneficiaries (generally speaking the GI producers), has similarities to but also differences from the trademark rights:

- While GIs denote a geographical origin of a good, trademarks denote a commercial origin of an enterprise.

- While comparable goods are registered with GIs, similar goods and services are registered with trademarks.

- While a GI is a name associated by tradition with a delineated area, a trademark is a badge of origin for goods and services.

- While a GI is a collective entitlement of public-private partnership, a trademark refers entirely to private rights. With GIs, the beneficiaries are always a community from which usually, regardless of who is indicated in the register as applicant, they have the right to use.[clarification needed] Trademarks distinguish goods and services between different undertakings, thus it is more individual (except collective trademarks which are still more private).[clarification needed]

- While the particular quality denoted by a GI is essentially related to a geographical area, although the human factor[clarification needed] may also play a part (collectively), with trademarks, even if there is any link to quality, it is essentially because of the producer and provider (individually).[clarification needed]

- While GIs are an already existing expression[clarification needed] and are used by existing producers or traders, a trademark is usually a new word or logo chosen arbitrarily.

- While GIs are usually only for products, trademarks are for products and services.

- While GIs cannot become numerous by definition[clarification needed], with trademarks there is no limit to the number that might be registered or used.

- While GIs may not normally qualify as trademarks because they are either descriptive or misleading and distinguish products from one region from those of another, trademarks normally do not constitute a geographical name as there is no essential link with the geographical origin of goods.

- While GIs protect names designating the origin of goods, trademarks – collective and certification marks where a GI sui generis system exists – protect signs or indications.

- While with GIs there is no conceptual uniform approach of protection (public law and private law / sui generis law and common law), the trademark concepts of protection are practically the same in all countries of the world (i.e., basic global understanding of the Madrid System). In other words, with GIs there is no international global consensus for protection other than TRIPS.

- While with GIs the administrative action is through public law, the enforcement by the interested parties of trademarks is through private law.

- While GIs lack a truly global registration system, trademarks global registration system is through the Madrid Agreement and Protocol.

- While GIs are very attractive for developing countries rich in traditional knowledge, the new world, e.g., Australia, with a different industry development model they are more prone to benefit from trademarks. In the new world, GI names from abroad arrive through immigrants and colonisation, leading to generic names deriving from the GIs from the old world.

Geographical indications have other similarities with trademarks. For example, they must be registered in order to qualify for protection, and they must meet certain conditions in order to qualify for registration. One of the most important conditions that most governments have required before registering a name as a GI is that the name must not already be in widespread use as the generic name for a similar product. Of course, what is considered a very specific term for a well-known local specialty in one country may constitute a generic term or genericized trademark for that type of product. For example, parmigiano cheese in Italy is generically known as Parmesan cheese in Australia and the United States .

Rural development effects

Geographical indications are generally applied to traditional products, produced by rural, marginal or indigenous communities over generations, that have gained a reputation on the local, national or international markets due to their specific unique qualities.

Producers can add value to their products through Geographical Indications by:

- communicating to consumers the product's characteristics, which derive from the climate, soil and other natural conditions in its particular geographical area;

- promoting the conservation of local traditional production processes; and

- protecting and adding value to the cultural identity of local communities.

The recognition and protection on the markets of the names of these products allows the community of producers to invest in maintaining the specific qualities of the product on which the reputation is built. Most importantly, as the reputation spreads beyond borders and demand grows, investment may be directed to the sustainablity of the environment where these products originate and are produced. In the International Trade Centre's "Guide to Geographical Indications: Linking Products and their Origins", authors Daniele Giovannucci, Professor Tim Josling, William Kerr, Bernard O'Connor and May T. Yeung clearly assert that geographical indications are by no means a panacea for the difficulties of rural development. They can however offer a comprehensive framework for rural development, since they can positively encompass issues of economic competitiveness, stakeholder equity, environmental stewardship, and socio-cultural value.[2] The application of circular economy will ensure socio-economic returns in the long-run to avoid growth at an environmental cost. This approach for GI development may also allow for investment together with promoting the reputation of the product along the lines of sustainability when and where possible.

Rural development impacts from geographical indications, referring to environmental protection, economic development and social well-being, can be:

- the strengthening of sustainable local food production and supply (except for non-agricultural GIs such as handicrafts);

- a structuring of the supply chain around a common product reputation linked to origin;

- greater bargaining power to raw material producers for better distribution so as for them to receive a higher retail price benefit percentage;

- capacity of producers to invest economic gains into higher quality to access niche markets, improving circular economy means throughout the value chain, protection against infringements such as free-riding from illegitimate producers, etc.;

- economic resilience in terms of increased and stabilised prices for the GI product to avoid the commodity trap through de-commodisation, or to prevent/minimise external shocks affecting the premium price percentage gains (usually varying from 20-25%);

- added value throughout the supply chain;

- spill-over effects such as new business and even other GI registrations;

- preservation of the natural resources on which the product is based and therefore protect the environment;

- preservation of traditions and traditional knowledge;

- identity based prestige;

- linkages to tourism.

None of these impacts are guaranteed and they depend on numerous factors, including the process of developing the geographical indications, the type and effects of the association of stakeholders, the rules for using the GI (or Code of Practice), the inclusiveness and quality of the collective dimension decision making of the GI producers association and quality of the marketing efforts undertaken.[citation needed]

International issues

Like trademarks, geographical indications are regulated locally by each country because conditions of registration such as differences in the generic use of terms vary from country to country. This is especially true of food and beverage names which frequently use geographical terms, but it may also be true of other products such as carpets (e.g. 'Shiraz'), handicrafts, flowers and perfumes.

When products with GIs acquire a reputation of international magnitude, some other products may try to pass themselves off as the authentic GI products. This kind of competition is often seen as unfair, as it may discourage traditional producers as well as mislead consumers. Thus the European Union has pursued efforts to improve the protection of GI internationally. Inter alia, the European Union has established distinct legislation to protect geographical names in the fields of wines, spirits, agricultural products including beer. A register for protected geographical indications and denominations of origin relating to products in the field of agriculture including beer, but excluding mineral water, was established (DOOR). Another register was set up for wine region names, namely the E-Bacchus register. A register of the geographical indications for spirits and for any other products is still missing in the European Union and most other countries in the world. A private database project (GEOPRODUCT directory) intends to close this gap. Accusations of 'unfair' competition should although be levelled with caution since the use of GIs sometimes comes from European immigrants who brought their traditional methods and skills with them.[3]

Paris convention and Lisbon agreement

International trade made it important to try to harmonize the different approaches and standards that governments used to register GIs. The first attempts to do so were found in the Paris Convention on trademarks (1883, still in force, 176 members), followed by a much more elaborate provision in the 1958 Lisbon Agreement on the Protection of Appellations of Origin and their Registration. 28 countries are parties to the Lisbon agreement: Algeria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Congo, Costa Rica, Cuba, Czech Republic, North Korea, France, Gabon, Georgia, Haiti, Hungary, Iran, Israel, Italy, Macedonia, Mexico, Moldova, Montenegro, Nicaragua, Peru, Portugal, Serbia, Slovakia, Togo and Tunisia. About 9000 geographical indications were registered by Lisbon Agreement members.

Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights

The WTO Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights ("TRIPS") defines "geographical indications" as indications that identify a good as "originating in the territory of a Member, or a region or locality in that territory, where a given quality, reputation or other characteristic of the good is essentially attributable to its geographic origin."[4]

In 1994, when negotiations on the WTO TRIPS were concluded, governments of all WTO member countries (164 countries, as of August 2016) had agreed to set certain basic standards for the protection of GIs in all member countries. There are, in effect, two basic obligations on WTO member governments relating to GIs in the TRIPS agreement:

- Article 22 of the TRIPS Agreement says that all governments must provide legal opportunities in their own laws for the owner of a GI registered in that country to prevent the use of marks that mislead the public as to the geographical origin of the good. This includes prevention of use of a geographical name which although literally true "falsely represents" that the product comes from somewhere else.[4]

- Article 23 of the TRIPS Agreement says that all governments must provide the owners of GI the right, under their laws, to prevent the use of a geographical indication identifying wines not originating in the place indicated by the geographical indication. This applies even where the public is not being misled, where there is no unfair competition and where the true origin of the good is indicated or the geographical indication is accompanied by expressions such as "kind", "type", "style", "imitation" or the like. Similar protection must be given to geographical indications identifying spirits.[4]

Article 22 of TRIPS also says that governments may refuse to register a trademark or may invalidate an existing trademark (if their legislation permits or at the request of another government) if it misleads the public as to the true origin of a good. Article 23 says governments may refuse to register or may invalidate a trademark that conflicts with a wine or spirits GI whether the trademark misleads or not.

Article 24 of TRIPS provides a number of exceptions to the protection of geographical indications that are particularly relevant for geographical indications for wines and spirits (Article 23). For example, Members are not obliged to bring a geographical indication under protection where it has become a generic term for describing the product in question. Measures to implement these provisions should not prejudice prior trademark rights that have been acquired in good faith; and, under certain circumstances — including long-established use — continued use of a geographical indication for wines or spirits may be allowed on a scale and nature as before.[4]

In the Doha Development Round of WTO negotiations, launched in December 2001, WTO member governments are negotiating on the creation of a 'multilateral register' of geographical indications. Some countries, including the EU, are pushing for a register with legal effect, while other countries, including the United States, are pushing for a non-binding system under which the WTO would simply be notified of the members' respective geographical indications.

Some governments participating in the negotiations (especially the European Communities) wish to go further and negotiate the inclusion of GIs on products other than wines and spirits under Article 23 of TRIPS. These governments argue that extending Article 23 will increase the protection of these marks in international trade. This is a controversial proposal, however, that is opposed by other governments including the United States who question the need to extend the stronger protection of Article 23 to other products. They are concerned that Article 23 protection is greater than required, in most cases, to deliver the consumer benefit that is the fundamental objective of GIs laws.

Geneva Act of the Lisbon Agreement

In 2015, The Geneva Act was adopted. It entered into force early-2020 with the accession of the European Union. The Geneva Act bridges the Lisbon system of Appellations of Origin, and the TRIPS system of Geographical Indications.

Differences in philosophy

One reason for the conflicts that occur between European and United States governments is a difference in philosophy as to what constitutes a "genuine" product. In Europe, the prevailing theory is that of terroir: that there is a specific property of a geographical area, and that dictates a strict usage of geographical designations. Thus, anyone with sheep of the right breeds can make Roquefort cheese if they are located in the part of France where that cheese is made, but nobody outside that part of France can make a blue sheep's milk cheese and call it Roquefort, even if they completely duplicate the process described in the definition of Roquefort. By contrast, in the United States, the naming is generally considered to be a matter of intellectual property. Thus, the name Grayson belongs to Meadowcreek Farms, and they have to a right to use it as a trademark. Nobody, even in Grayson County, Virginia, can call their cheese Grayson, while Meadowcreek Farms, if they bought up another farm elsewhere in the United States, even if nowhere near Grayson County, could use that name. It is considered that their need to preserve their reputation as a company is the quality guarantee. This difference causes most of the conflict between the United States and Europe in their attitudes toward geographical names.[5]

However, there is some overlap, particularly with American products adopting a European way of viewing the matter.[6] The most notable of these are crops: Vidalia onions, Florida oranges, and Idaho potatoes. In each of these cases, the state governments of Georgia, Florida, and Idaho registered trademarks, and then allowed their growers—or in the case of the Vidalia onion, only those in a certain, well-defined geographical area within the state—to use the term, while denying its use to others. The European conception is increasingly gaining acceptance in American viticulture; also, vintners in the various American Viticultural Areas are attempting to form well-developed and unique identities as New World wine gains acceptance in the wine community. Finally, the United States has a long tradition of placing relatively strict limitations on its native forms of whiskey; particularly notable are the requirements for labeling a product "straight whiskey" (which requires the whiskey to be produced in the United States in accordance with certain standards) and the requirement, enforced by federal law and several international agreements, (NAFTA, among them) that a product labeled Tennessee whiskey be a straight Bourbon whiskey produced in the state of Tennessee .

Conversely, some European products have adopted a more American system: a prime example is Newcastle Brown Ale, which received an EU protected geographical status in 2000. When the brewery moved from Tyneside to Tadcaster in North Yorkshire (about 150 km away) in 2007 for economic reasons, the status had to be revoked.

See also

- Appellation (wine)

- Country of origin

- Geographical Indication Registry (India)

- Geographical Indications of Goods (Registration and Protection) Act, 1999

- Protected Geographical Status (European Union)

- Terroir

Notes

- 1.^ See also the Paris Convention, the Madrid Agreement, the Lisbon Agreement, the Geneva Act.

References

- ↑ Tosato, Andrea (2013). "The Protection of Traditional Foods in the EU: Traditional Specialities Guaranteed". European Law Journal 19 (4): 545–576. doi:10.1111/eulj.12040.

- ↑ Giovannucci, Daniele; Josling, Timothy E.; Kerr, William; O'Connor, Bernard; Young, May T. (2009). "Guide to Geographical Indications: Linking Products and their Origins". Geneva: International Trade Center. https://fsi.stanford.edu/publications/guide_to_geographical_indications_linking_products_and_their_origins/. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ↑ "Geographical Indications and the challenges for ACP countries, by O'Connor and Company". http://agritrade.cta.int/en/content/view/full/1794.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "WTO - intellectual property (TRIPS) - agreement text - standards". http://www.wto.org/english/docs_e/legal_e/27-trips_04b_e.htm.

- ↑ Zappalaglio, Andrea (2015). "The Protection of Geographical Indications: Ambitions and Concrete Limitations". University of Edinburgh Student Law Review 2: 88. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277867915_The_Protection_of_Geographical_Indications_Ambitions_and_Concrete_Limitations. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ↑ Le Goffic & Zappalaglio 'The Role Played by the US Government in Protecting Geographical Indications' World Development, 2017, vol. 98, issue C, 35-44

External links

- FAO guide: Linking people, places and products (2009)

- Organization for an International Geographical Indications Network

- World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO): Geographical Indications

- Caslon Analytics Appellations

- Wines and mangoes as geographical Indications

- A research project on geographical indications