Social:Kuliak languages

| Kuliak | |

|---|---|

| Rub | |

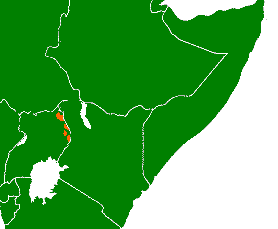

| Geographic distribution | Karamoja region, northeastern Uganda |

| Linguistic classification | Nilo-Saharan?

|

| Proto-language | Proto-Kuliak |

| Subdivisions |

|

| Glottolog | kuli1252[1] |

| |

The Kuliak languages, also called the Rub languages,[2] or Nyangiyan languages[3] are a group of languages spoken by small relict communities in the mountainous Karamoja region of northeastern Uganda.

Nyang'i and Soo are moribund, with a handful of elderly speakers. However, Ik is vigorous and growing.

Word order in Kuliak languages is verb-initial.[4]

Names

History

The Kuliak languages have previously had a much more extensive range in the past. Kuliak loanwords in the Luhya, Gusii, Kalenjin and Sukuma languages show that these peoples inhabited western Kenya and the southern parts of Lake Victoria before being absorbed by the ancestors of these Bantu and Nilotic speakers. These now extinct Kuliak peoples are known as the "Southern Rub". The Southern Rub lived as far south as Lake Eyasi, as shown by Kuliak loanwords in Hadza and Sandawe, and possibly as far east as the Kilimanjaro Region, as shown by Kuliak loanwords in the Chaga and Thagiicu languages.[5][6]

Classification

Internal

According to the classification of Heine (1976),[7] Soo and Nyang'i form a subgroup, Western Kuliak, while Ik stands by itself.

| Kuliak |

| ||||||||||||

According to Schrock (2015), "Dorobo" is a spurious language, is not a fourth Kuliak language, and may at most be a dialect of Ik.[8]

Heine finds the following numbers of correspondences between the languages on the 200-word Swadesh list:

- Soo – Nyang'i: 43.2%

- Nyang'i – Ik: 26.7%

- Soo – Ik: 24.2%

External

Bender (1989) had classified the Kuliak languages within the Eastern Sudanic languages. Later, Bender (2000) revised this position by placing Kuliak as basal branch of Nilo-Saharan. Glottolog treats Kuliak as an independent language family and does not accept Nilo-Saharan as a valid language family.

An early suggestion for Ik as a member of Afroasiatic was made by Archibald Tucker in the 1960s; this was criticized as weak and abandoned by the 1980s.[9]

Evolution

The following sound correspondences are identified by Bernd Heine (1976),[7] who proposes also corresponding Proto-Kuliak reconstructions.

| Ik | Tepes | Nyang'i | Proto-Kuliak | Phonological environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | b ~ p | b | *b | |

| ɓ | ɓ | ɓ | *ɓ | |

| ɗ ~ d | d | d | *d | |

| dz | ∅ | ∅ | *dz | Initially. Fricative z in Dorobo. |

| d | s | (?) | Medially. No reflexes known in Nyang'i. | |

| ɟ ~ ʄ | ɟ | ɟ | *ɟ | |

| g | g | g | *g | Initially, before back vowels |

| ɟ | g | ɟ | Initially, before front vowels | |

| g | ∅ | ∅ | Medially | |

| f | p | p | *p | |

| t | t | t | *t | |

| ts | c | c | *c | |

| c | k | k | *kj | Initially and medially |

| h | k | k | Finally | |

| k | k | k | *k | |

| kw | w | kw | *kw | Word-initially |

| k | ∅ | ∅ | *kʰ | |

| tsʼ | ʄ | ʄ | *cʼ | Initially |

| s | s | s | Medially | |

| kʼ | ɠ | ɠ | *kʼ | |

| s | s | s | *s | Initially |

| r | s | s | Medially | |

| ɬ | l | ɬ | *ɬ | Initially |

| ɬ | l | iɬ | Finally | |

| h | ∅ | ∅ | *h | Initially |

| ∅ | ʔ | ∅ | Finally | |

| z | (?) | s | *z | No reflex known in Tepes |

| m | m | m | *m | |

| n | n | n | *n | |

| ɲ | ɲ | ɲ | *ɲ | |

| ŋ | ŋ | ŋ | *ŋ | Initially, by default |

| ɲ | ŋ | ŋ | Initially, before *ɛ | |

| r | ? | ɲ | Medially and finally | |

| l | l | l | *l | Finally, a plosive /t/ in Dorobo. |

| r | r | r | *r | Initially and at the end of monosyllabic words |

| r | ∅ | r | Elsewhere | |

| r | r | r | *rr | Medially |

| ∅ | j | ∅ | *j | Initially and finally |

| j | j | j | Medially | |

| w | w | w | *w | Default |

| w ~ ∅ | ∅ | w | Finally after *k, *g |

| Ik | Tepes | Nyang'i | Proto-Kuliak | Phonological environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | a | a | *a | Default |

| a | a | ɛ | Preceded by any non-open vowel | |

| a | e | e | Followed by a high vowel *i, *u | |

| a | ɛ | ɛ | Unstressed, when followed by a semivowel *j, *w | |

| ɛ | ɛ | ɛ | *ɛ | In Tepes and Nyang'i, /e/ and /ɛ/ can alternate morphophonologically. |

| e | e | e | *e | |

| i | e | e | *ẹ | |

| e | i | i | *I | |

| i | i | i | *i | |

| ɔ | ɔ | ɔ | *ɔ | In Tepes and Nyang'i, /o/ and /ɔ/ can alternate morphophonologically. |

| o | o | o | *o | |

| u | o | o | *ọ | |

| o | u | u | *U | |

| u | u | u | *u |

For other vowel correspondences, Heine reconstructs clusters of vowels:

- Front vowel + *o: yields Ik /ɔ/ or /o/, a front vowel in Tepes and Nyang'i.

- Close vowel + *a or *ɔ: cluster retained in Nyang'i, contracted to a single vowel in the other languages.

- *a, *i + *e, *i, *u: cluster retained in Ik, contracted to a single vowel in the other languages.

- *ui: yields Ik /i/, Tepes /u/ or /wi/, Nyang'i /wi/.

Heine reconstructs two classes of stress in Proto-Kuliak: "primary", which could occur in any position and remains in place in all Kuliak languages, and "secondary", which always occurred on the 2nd syllable of a word, and remains there in Ik and Nyang'i, but shifts to the first syllable in Tepes.

Blench[10] notes that Kuliak languages do not have extensive internal diversity and clearly had a relatively recent common ancestor. There are many monosyllabic VC (vowel + consonant) lexical roots in Kuliak languages, which is typologically unusual among Nilo-Saharan languages and is more typical of some Australian languages such as Kunjen. Blench considers these VC roots to have cognates in other Nilo-Saharan languages, and suggests that the VC roots may have been eroded from earlier Nilo-Saharan roots that had initial consonants.[10]

Significant influences from Cushitic languages,[11] and more recently Eastern Nilotic languages, are observable in the vocabulary and phonology of Kuliak languages. Blench[10] notes that Kuliak appears to retain a core of non-Nilo-Saharan vocabulary, suggesting language shift from an indigenous language like that seen in Dahalo.

Numerals

Comparison of numerals in individual languages:[12]

| Language | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ik (1) | kɔ̀nʊ̀kᵓ (lit. and it's one) | lèɓètsìn (lit. and it's two) | àɗìn (lit. and it's three) | tsʼàɡùsìn (lit. and it's four) | tùdìn (lit. and it's five) | tudini ńda kɛɗɪ kɔn (5+ 1) | tudini ńda kiɗi léɓetsᵉ (5+ 2) | tudini ńda kiɗi aɗ (5+ 3) | tudini ńda kiɗi tsʼaɡús (5+ 4) | tomín |

| Ik (2) | kɔnᵃ | léɓetsᵃ | aɗᵃ / aɗᵉ | tsʔaɡúsᵃ | túdᵉ | ńda-keɗi-kɔnᵃ (5+ 1) | ńda-kiɗi-léɓetsᵃ (5+ 2) | ńda-kiɗiá-aɗᵉ (5+ 3) | ńda-kiɗi-tsʔaɡúsᵃ (5+ 4) | tomín |

| Nyang'i | nardok | nɛʔɛc | iyʔɔn | nowʔe | tud | mɔk kan kapei | mɔk tomin | |||

| Soo (Tepes) (1) | nɛ́dɛ̀s | ínɛ̀'bɛ́c | ínì'jɔ̀n | ín'ùáʔ | íntùd | ˌíntùd ká ˈnɛ́dɛ̀s (5+ 1) | ˌíntùd ká ínɛ̀'bɛ̀c (5+ 2) | ˌíntùd ká ínì'jɔ́n (5+ 3) | ˌíntùd ká ínùáʔ (5+ 4) | mì'míɾínìk |

| Soo (Tepes) (2) | ɛdɛs | nɛbɛc | iyon | nowa | tuɗ | tuɗ ka nɪ ɛdɛs (5+ 1) | tuɗ ka nɪ nɛbɛc (5+ 2) | tuɗ ka nɪ iyon (5+ 3) | tuɗ ka nɪ nowa (5+ 4) | tuɗ en-ek iɠe (hand-PL all) |

See also

- List of Proto-Kuliak reconstructions (Wiktionary)

References

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Kuliak". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/kuli1252.

- ↑ Ehret, Christopher (2001) A Historical-Comparative Reconstruction of Nilo-Saharan (SUGIA, Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika: Beihefte 12), Cologne: Rüdiger Köppe Verlag, ISBN 3896450980.

- ↑ Ethiopians and East Africans: The Problem of Contacts. East African Publishing House. 1974. p. 35. https://books.google.com/books?id=xysSAQAAIAAJ.

- ↑ Beer, Sam, Amber McKinney, Lokiru Kosma 2009. The So Language: A Grammar Sketch. m.s.

- ↑ An African Classical Age: Eastern and Southern Africa in World History, 1000 B.C. to A.D. 400. pp. 131, 185, 193–197. https://www.google.com/books/edition/An_African_Classical_Age/1i-IBmCeNhUC?hl=en.

- ↑ The Khoesan Languages. p. 475-478. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Khoesan_Languages/QvpwwRLYai0C?hl=en.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Heine, Bernd. 1976. The Kuliak Languages of Eastern Uganda. Nairobi: East African Publishing House.

- ↑ Schrock, Terrill. 2015. On Whether 'Dorobo' was a Fourth Kuliak Language. Studies in African Linguistics 44: 47-58.

- ↑ Hetzron, Robert (1980). "The Limits of Cushitic". Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika 2: 12–13.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Blench, Roger. Segment reversal in Kuliak and its relationship to Nilo-Saharan.

- ↑ Lamberti, Marcello. 1988. Kuliak and Cushitic: A Comparative Study. (Studia linguarum africae orientalis, 3.) Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

- ↑ Chan, Eugene (2019). "The Nilo-Saharan Language Phylum". Numeral Systems of the World's Languages. https://lingweb.eva.mpg.de/channumerals/Nilo-Saharan.htm.

- Laughlin, C. D. (1975). "Lexicostatistics and the Mystery of So Ethnolinguistic Relations" in Anthropological Linguistics 17:325-41.

- Fleming, Harold C. (1982). "Kuliak External Relations: Step One" in Nilotic Studies (Proceedings of the International Symposium on Languages and History of the Nilotic Peoples, Cologne, January 4–6, 1982, Vol 2, 423–478.

- Blench, Roger M. (2006). Archaeology, Language, and the African Past. Lanham: Altamira Press.

Template:Nilo-Saharan families

|