Social:Life of William Shakespeare

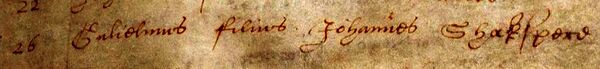

William Shakespeare was an actor, playwright, poet, and theatre entrepreneur in London during the late Elizabethan and early Jacobean eras. He was baptised on 26 April 1564[lower-alpha 1] in Stratford-upon-Avon in Warwickshire, England , in the Holy Trinity Church. At the age of 18, he married Anne Hathaway, with whom he had three children. He died in his home town of Stratford on 23 April 1616, aged 52.

Though more is known about Shakespeare's life than those of most other Elizabethan and Jacobean writers, few personal biographical facts survive, which is unsurprising in the light of his social status as a commoner, the low esteem in which his profession was held, and the general lack of interest of the time in the personal lives of writers.[2][3][4][5][6] Information about his life derives from public rather than private documents: vital records, real estate and tax records, lawsuits, records of payments, and references to Shakespeare and his works in printed and hand-written texts. Nevertheless, hundreds of biographies have been written and more continue to be, most of which rely on inferences and the historical context of the 70 or so hard facts recorded about Shakespeare the man, a technique that sometimes leads to embellishment or unwarranted interpretation of the documented record.[7][8]

Early life

Family origins

William Shakespeare[lower-alpha 2] was born in Stratford-upon-Avon. His exact date of birth is not known—the baptismal record was dated 26 April 1564—but has been traditionally taken to be 23 April 1564, which is also the Feast Day of Saint George, the patron saint of England. He was the first son and the first surviving child in the family; two earlier children, Joan and Margaret, had died early.[9] Then a market town of about 2000 residents approximately 100 miles (160 km) northwest of London, Stratford was a centre for the marketing, distribution, and slaughter of sheep; for hide tanning and wool trading; and for supplying malt to brewers of ale and beer.

His parents were John Shakespeare, a successful glover originally from Snitterfield in Warwickshire, and Mary Arden, the youngest daughter of John's father's landlord, a member of the local gentry. The couple married around 1557 and lived on Henley Street when Shakespeare was born, purportedly in a house now known as Shakespeare's Birthplace. They had eight children: Joan (baptised 15 September 1558, died in infancy), Margaret (bap. 2 December 1562 – buried 30 April 1563), William, Gilbert (bap. 13 October 1566 – bur. 2 February 1612), Joan (bap. 15 April 1569 – bur. 4 November 1646), Anne (bap. 28 September 1571 – bur. 4 April 1579), Richard (bap. 11 March 1574 – bur. 4 February 1613) and Edmund (bap. 3 May 1580 – bur. London, 31 December 1607).[10]

Shakespeare's family was above average materially during his childhood. His father's business was thriving at the time of William's birth. John Shakespeare owned several properties in Stratford and had a profitable—though illegal—sideline of dealing in wool. He was appointed to several municipal offices and served as an alderman in 1565, culminating in a term as bailiff, the chief magistrate of the town council, in 1568. For reasons unclear to history he fell upon hard times, beginning in 1576, when William was 12.[11] He was prosecuted for unlicensed dealing in wool and for usury, and he mortgaged and subsequently lost some lands he had obtained through his wife's inheritance that would have been inherited by his eldest son. After four years of non-attendance at council meetings, he was finally replaced as burgess in 1586.

Boyhood and education

A close analysis of Shakespeare's works compared with the standard curriculum of the time confirms that Shakespeare had received a grammar school education.[12][13][14][15][16] The King Edward VI School at Stratford was on Church Street, less than a quarter of a mile from Shakespeare's home and within a few yards from where his father sat on the town council. It was free to all male children, and the evidence[clarification needed] indicates that John Shakespeare sent his sons there for a grammar school education, though no attendance records survive. Shakespeare would have been enrolled when he was 7, in 1571.[17][12] Classes were held every day except on Sundays, with a half-day off on Thursdays, year-round. The school day typically ran from 6 a.m. to 5 p.m. (from 7 a.m. to 4 p.m. in winter) with a two-hour break for lunch.[citation needed]

Grammar schools varied in quality during the Elizabethan era, but the grammar curriculum was standardised by royal decree throughout England,[18][19] and the school would have provided an intensive education in Latin grammar and literature—"as good a formal literary training as had any of his contemporaries".[20] Most of the day was spent in the rote learning of Latin. By the time he was 10, Shakespeare was translating Cicero, Terence, Virgil and Ovid. As a part of this education, the students performed Latin plays to better understand rhetoric. By the end of their studies at age 14, grammar school pupils were quite familiar with the great Latin authors, and with Latin drama and rhetoric.[21]

Shakespeare is unique among his contemporaries in the extent of figurative language derived from country life and nature.[22] The familiarity with the animals and plants of the English countryside exhibited in his poems and plays, especially the early ones, suggests that he lived the childhood of a typical country boy, with easy access to rural nature and a propensity for outdoor sports, especially hunting.[23][24][25]

Marriage

On 27 November 1582, Shakespeare was issued a special licence to marry Anne Hathaway, the daughter of the late Richard Hathaway, a yeoman farmer of Shottery, about a mile west of Stratford (the clerk mistakenly recorded the name "Anne Whateley").[26] He was 18 and she was 26. The licence, issued by the consistory court of the diocese of Worcester, 21 miles west of Stratford, allowed the two to marry with only one proclamation of the marriage banns in church instead of the customary three successive Sundays.[27]

Since he was under age and could not stand as surety, and since Hathaway's father had died, two of Hathaway's neighbours – Fulk Sandalls and John Richardson – posted a bond of £40 the next day to ensure: that no legal impediments existed to the union; that the bride had the consent of her "friends" (persons acting in lieu of parents or guardians if she was under age); and to indemnify the bishop issuing the licence from any possible liability for the wife and any children should any impediment nullify the marriage.[28][29] Neither the exact day, nor place, of their marriage is now known.

The reason for the special licence became apparent six months later with the baptism of their first daughter, Susanna, on 26 May 1583. Their twin children – a son Hamnet and a daughter Judith (named after Shakespeare's neighbours Hamnet and Judith Sadler) – were baptised on 2 February 1585, before Shakespeare was 21 years of age.

Lost years

After the baptism of the twins in 1585, and except for being party to a lawsuit to recover part of his mother's estate which had been mortgaged and lost by default, Shakespeare leaves no historical traces until Robert Greene jealously alludes to him as part of the London theatrical scene in 1592. This seven-year period – known as the "lost years" to Shakespeare scholars – was filled by early biographers with inferences drawn from local traditions and by more recent biographers with surmises about the onset of his acting career deduced from textual and bibliographic hints and the surviving records of the various troupes of players, acting at that time. While this lack of records bars any certainty about his activity during those years, it is certain that by the time of Greene's attack on the 28-year-old, Shakespeare had acquired a reputation as an actor and burgeoning playwright.

Shakespeare myths

Several hypotheses have been put forth to account for his life during this time, and a number of accounts are given by his earliest biographers.

According to Shakespeare's first biographer Nicholas Rowe, Shakespeare fled Stratford after he got in trouble for poaching deer from local squire Thomas Lucy, and that he then wrote a scurrilous ballad about Lucy. It is also reported, according to a note added by Samuel Johnson to the 1765 edition of Rowe's Life, that Shakespeare minded the horses for theatre patrons in London. Johnson adds that the story had been told to Alexander Pope by Rowe.[30]

In his Brief Lives, written 1669–96, John Aubrey reported that Shakespeare had been a "schoolmaster in the country" on the authority of William Beeston, son of Christopher Beeston, who had acted with Shakespeare in Every Man in His Humour (1598) as a fellow member of the Lord Chamberlain's Men.[31]

Later speculation

In 1985 E. A. J. Honigmann proposed that Shakespeare acted as a schoolmaster in Lancashire,[32] on the evidence found in the 1581 will of a member of the Houghton family, referring to plays and play-clothes and asking his kinsman Thomas Hesketh to take care of "William Shakeshaft, now dwelling with me". Honigmann proposed that John Cottam, Shakespeare's reputed last schoolmaster, recommended the young man.

Another idea is that Shakespeare may have joined Queen Elizabeth's Men in 1587, after the sudden death of actor William Knell in a fight while on a tour which later took in Stratford. Samuel Schoenbaum speculates that, "Maybe Shakespeare took Knell's place and thus found his way to London and stage-land."[33] Shakespeare's father John, as High Bailiff of Stratford, was responsible for the acceptance and welfare of visiting theatrical troupes.[34]

London and theatrical career

Though Shakespeare is known today primarily as a playwright and poet, his main occupation was as a player and sharer in an acting troupe. How or when Shakespeare got into acting is unknown. The profession was unregulated by a guild that could have established restrictions on new entrants to the profession—actors were literally "masterless men"—and several avenues existed to break into the field in the Elizabethan era.[35][36]

Certainly Shakespeare had many opportunities to see professional playing companies in his youth. Before being allowed to perform for the general public, touring playing companies were required to present their play before the town council to be licensed. Players first acted in Stratford in 1568, the year that John Shakespeare was bailiff. Before Shakespeare turned 20, the Stratford town council had paid for at least 18 performances by at least 12 playing companies. In one playing season alone, that of 1586–87, five different acting troupes visited Stratford.[37][38]

By 1592 Shakespeare was a player/playwright in London, and he had enough of a reputation for Robert Greene to denounce him in the posthumous Greenes, Groats-worth of Witte, bought with a million of Repentance as "an upstart crow, beautified with our feathers, that with his Tygers hart wrapt in a Players hyde, supposes he is as well able to bombast out a blanke verse as the best of you: and being an absolute Johannes factotum, is in his owne conceit the onely Shake-scene in a countrey." (The italicized line parodies the phrase, "Oh, tiger's heart wrapped in a woman's hide" from Shakespeare's Henry VI, part 3.)[39]

By late 1594, Shakespeare was part-owner of a playing company, known as the Lord Chamberlain's Men—like others of the period, the company took its name from its aristocratic sponsor, in this case the Lord Chamberlain. The group became so popular that, after the death of Elizabeth I and the coronation of James I (1603), the new monarch adopted the company, which then became known as the King's Men, after the death of their previous sponsor. Shakespeare's works are written within the frame of reference of the career actor, rather than a member of the learned professions or from scholarly book-learning.[lower-alpha 3]

The Shakespeare family had long sought armorial bearings and the status of gentleman. William's father John, a bailiff of Stratford with a wife of good birth, was eligible for a coat of arms and applied to the College of Heralds, but evidently his worsening financial status prevented him from obtaining it. The application was successfully renewed in 1596, most probably at the instigation of William himself as he was the more prosperous at the time. The motto "Non sanz droict" ("Not without right") was attached to the application, but it was not used on any armorial displays that have survived. The theme of social status and restoration runs deep through the plots of many of his plays, and at times Shakespeare seems to mock his own longing.[41]

By 1596, Shakespeare had moved to the parish of St. Helen's, Bishopsgate, and by 1598 he appeared at the top of a list of actors in Every Man in His Humour written by Ben Jonson. He is also listed among the actors in Jonson's Sejanus His Fall. Also by 1598, his name began to appear on the title pages of his plays, presumably as a selling point.[citation needed]

There is a tradition that Shakespeare, in addition to writing many of the plays his company enacted and concerned with business and financial details as part-owner of the company, continued to act in various parts, such as the ghost of Hamlet's father, Adam in As You Like It, and the Chorus in Henry V.[42]

He appears to have moved across the River Thames to Southwark sometime around 1599. In 1604, Shakespeare acted as a matchmaker for his landlord's daughter. Legal documents from 1612, when the case was brought to trial, show that Shakespeare was a tenant of Christopher Mountjoy, a Huguenot tire-maker (a maker of ornamental headdresses) in the northwest of London in 1604. Mountjoy's apprentice Stephen Bellott wanted to marry Mountjoy's daughter. Shakespeare was enlisted as a go-between, to help negotiate the terms of the dowry. On Shakespeare's assurances, the couple married. Eight years later, Bellott sued his father-in-law for delivering only part of the dowry. During the Bellott v Mountjoy case one witness, in a deposition, said that Christopher Mountjoy called on Shakespeare and encouraged him to persuade Stephen Belott to the marriage of his daughter. Then Shakespeare was called to testify, and according to the record, said that Belott was "a very good and industrious servant". Shakespeare then contradicted the deposition, and testified that it was Mountjoy's wife who had invited and encouraged Shakespeare to persuade Belott to marry the Mountjoy’s daughter. When it came to specifics about the size of the dowry and promised inheritance due the daughter, Shakespeare did not remember. A second set of questions was prepared for Shakespeare to testify again, but that appears not to have happened. The case was then turned over to the elders of the Huguenot church for arbitration.[43]

Business affairs

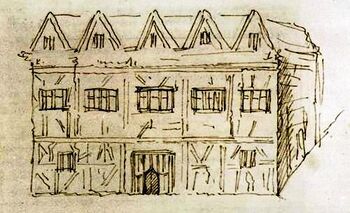

By the early 17th century, Shakespeare had become very prosperous. Most of his money went to secure his family's position in Stratford. Shakespeare himself seems to have lived in rented accommodation while in London. According to John Aubrey, he travelled to Stratford to stay with his family for a period each year.[44] Shakespeare grew rich enough to buy the second-largest house in Stratford, New Place, which he acquired in 1597 for £60 from William Underhill.

The Stratford chamberlain's accounts in 1598 record a sale of stone to the council from "Mr Shaxpere", which may have been related to remodelling work on the newly purchased house.[45] The purchase was thrown into doubt when evidence emerged that Underhill, who died shortly after the sale, had been poisoned by his oldest son, but the sale was confirmed by the new heir Hercules Underhill when he came of age in 1602.[46]

In 1598 the local council ordered an investigation into the hoarding of grain, as there had been a run of bad harvests causing a steep increase in prices. Speculators were acquiring excess quantities in the hope of profiting from scarcity. The survey includes Shakespeare's household, recording that he possessed ten-quarters of malt. This has often been interpreted as evidence that he was listed as a hoarder. Others argue that Shakespeare's holding was not unusual. According to Mark Eccles, "the schoolmaster, Mr. Aspinall, had eleven quarters, and the vicar, Mr. Byfield, had six of his own and four of his sister's".[45] Samuel Schoenbaum and B.R. Lewis, however, suggest that he purchased the malt as an investment, since he later sued a neighbour, Philip Rogers, for an unpaid debt for twenty bushels of malt.[45] Bruce Boehrer argues that the sale to Rogers, over six installments, was a kind of "wholesale to retail" arrangement, since Rogers was an apothecary who would have used the malt as raw material for his products.[45] Boehrer comments that,

Shakespeare had established himself in Stratford as the keeper of a great house, the owner of large gardens and granaries, a man with generous stores of barley which one could purchase, at need, for a price. In short, he had become an entrepreneur specialising in real estate and agricultural products, an aspect of his identity further enhanced by his investments in local farmland and farm produce.[47]

Shakespeare's biggest acquisitions were land holdings and a lease on tithes in Old Stratford, to the north of the town. He bought a share in the lease on tithes for £440 in 1605, giving him income from grain and hay, as well as from wool, lamb and other items in Stratford town. He purchased 107 acres of farmland for £320 in 1607, making two local farmers his tenants. Boehrer suggests he was pursuing an "overall investment strategy aimed at controlling as much as possible of the local grain market", a strategy that was highly successful.[47] In 1614 Shakespeare's profits were potentially threatened by a dispute over enclosure, when local businessman William Combe attempted to take control of common land in Welcombe, part of the area over which Shakespeare had leased tithes. The town clerk Thomas Greene, who opposed the enclosure, recorded a conversation with Shakespeare about the issue. Shakespeare said he believed the enclosure would not go through, a prediction that turned out to be correct. Greene also recorded that Shakespeare had told Greene's brother that "I was not able to bear the enclosing of Welcombe". It is unclear from the context whether Shakespeare is speaking of his own feelings, or referring to Thomas's opposition.[lower-alpha 4]

Shakespeare's last major purchase was in March 1613, when he bought an apartment in a gatehouse in the former Blackfriars priory;[51] The Gatehouse was near Blackfriars theatre, which Shakespeare's company used as their winter playhouse from 1608. The purchase was probably an investment, as Shakespeare was living mainly in Stratford by this time, and the apartment was rented out to one John Robinson. Robinson may be the same man recorded as a labourer in Stratford, in which case it is possible he worked for Shakespeare. He may be the same John Robinson who was one of the witnesses to Shakespeare's will.[52]

Later years and death

Rowe was the first biographer to pass down the tradition that Shakespeare retired to Stratford some years before his death;[53] but retirement from all work was uncommon at that time,[54] and Shakespeare continued to visit London. In 1612 he was called as a witness in the Bellott v Mountjoy case.[55][56] A year later he was back in London to make the Gatehouse purchase.

In June 1613 Shakespeare's daughter Susanna was slandered by John Lane, a local man who claimed she had caught gonorrhea from a lover. Susanna and her husband Dr John Hall sued for slander. Lane failed to appear and was convicted. From November 1614 Shakespeare was in London for several weeks with his son-in-law, Hall.[57]

In the last few weeks of Shakespeare's life, the man who was to marry his younger daughter Judith — a tavern-keeper named Thomas Quiney — was charged in the local church court with "fornication". A woman named Margaret Wheeler had given birth to a child and claimed it was Quiney's; she and the child both died soon after. Quiney was thereafter disgraced, and Shakespeare revised his will to ensure that Judith's interest in his estate was protected from possible malfeasance on Quiney's part.

Shakespeare died on 23 April 1616 (the presumed day of his birth and the feast day of St. George, patron of England), at the reputed age of 52.[lower-alpha 5] He died within a month of signing his will, a document which he begins by describing himself as being in "perfect health". No extant contemporary source explains how or why he died. After half a century had passed, John Ward, the vicar of Stratford, wrote in his notebook: "Shakespeare, Drayton and Ben Jonson had a merry meeting and, it seems, drank too hard, for Shakespeare died of a fever there contracted."[58][59] It is certainly possible he caught a fever after such a meeting, for Shakespeare knew Jonson and Drayton. Of the tributes that started to come from fellow authors, one — by James Mabbe printed in the First Folio — refers to his relatively early death: "We wondered, Shakespeare, that thou went'st so soon / From the world's stage to the grave's tiring room."[60]

Shakespeare was survived by his wife Anne and by two daughters, Susanna and Judith. His son Hamnet had died in 1596. His last surviving descendant was his granddaughter Elizabeth Hall, daughter of Susanna and John Hall. There are no direct descendants of the poet and playwright alive today, but the diarist John Aubrey recalls in his Brief Lives that William Davenant, his godson, was "contented" to be believed Shakespeare's actual son. Davenant's mother was the wife of a vintner at the Crown Tavern in Oxford, on the road between London and Stratford, where Shakespeare would stay when travelling between his home and the capital.[61]

Shakespeare is buried in the chancel of Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon. He was granted the honour of burial in the chancel not because of his fame as a playwright but because he had purchased a share of the tithe in the church for £440 (a considerable sum of money at the time). A monument on the wall nearest his grave, probably placed by his family,[62] features a bust showing Shakespeare posed in the act of writing. Every year, on his assumed birthday, a new quill pen is placed in the writing hand of the bust. He is believed to have written the epitaph on his tombstone.[63]

Good friend, for Jesus' sake forbear,

To dig the dust enclosed here.

Blest be the man that spares these stones,

And cursed be he that moves my bones.

See also

- Shakespeare's Way

- Religious views of William Shakespeare

- Reputation of William Shakespeare

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Dates follow the Julian calendar, used in England throughout Shakespeare's lifespan, but with the start of the year adjusted to 1 January (see Old Style and New Style dates). Under the Gregorian calendar, adopted in Catholic countries in 1582, Shakespeare died on 3 May 1616,[1]

- ↑ Also spelled Shakspere, Shaksper and Shake-speare, as spelling in Elizabethan times was not fixed and absolute. See Spelling of Shakespeare's name.

- ↑ William Allan Neilson and Ashley Horace Thorndike, in their book The Facts about Shakespeare (1915), write: "Records amply establish the identity between Shakespeare the actor and the writer. ... The extent of observation and knowledge in the plays is, indeed, remarkable but it is not accompanied by any indication of thorough scholarship, or a detailed connection with any profession outside of the theater...".[40]

- ↑ Schoenbaum concludes that "any attempt to interpret the passage is guesswork, and no more".[48] Lois Potter suggests that the word "bear" (spelled "beare" in the original) was intended for "bar"—meaning that Greene would not be able to stop the enclosure. [49][50]

- ↑ His age and the date are inscribed in Latin on his funerary monument: AETATIS 53 DIE 23 APR.

References

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, p. xv.

- ↑ Bate 1998, p. 4.

- ↑ Southworth 2000, p. 5.

- ↑ Wells 1997, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Bryson 2007, pp. 17–19.

- ↑ Halliwell-Phillipps 1907, pp. v–vi.

- ↑ Holderness 2011, p. 19.

- ↑ Ellis 2012, pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Potter 2012, pp. 1, 10.

- ↑ Chambers 1930b, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Schoone-Jongen 2008, p. 13.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Honan 1998, p. 43.

- ↑ Potter 2012, p. 48.

- ↑ Bate 1998, p. 8.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 62–63.

- ↑ Ellis 2012, p. 41.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 63.

- ↑ Baldwin 1944, pp. 179–180, 183.

- ↑ Cressy 1975, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Baldwin 1944, pp. 117, 663.

- ↑ Bate 1998, pp. 83–87.

- ↑ Chambers 1930a, p. 287.

- ↑ Chambers 1930a, pp. 254, 545.

- ↑ Ellis 2012, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Spurgeon 2004, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ Schoone-Jongen 2008, p. 11.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 75–79.

- ↑ Chambers 1930b, pp. 43–46.

- ↑ Loomis 2002, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1991, p. 75.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Honigmann 1985, pp. 41–48.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1979, p. 43.

- ↑ Pierce 2006, p. 3.

- ↑ Bentley 1984, p. 6.

- ↑ Ingram 2000, p. 155.

- ↑ Schoone-Jongen 2008, p. 15.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 115.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1977, pp. 151–158.

- ↑ Neilson & Thorndike 1915, pp. 164–165.

- ↑ Greenblatt 2005, pp. 76–86.

- ↑ Ackroyd 2006, pp. 234–236.

- ↑ Rowse 1963, p. 337-339.

- ↑ Honan 1998, p. 151.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 Boehrer 2013, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, p. 234.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Boehrer 2013, p. 90.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1987, pp. 284–285.

- ↑ Potter 2012, p. 404.

- ↑ Palmer & Palmer 1999, p. 96.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1977, pp. 272–274.

- ↑ Pogue 2006, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Ackroyd 2006, p. 476.

- ↑ Honan 1998, pp. 382–383.

- ↑ Honan 1998, p. 326.

- ↑ Ackroyd 2006, pp. 462–464.

- ↑ Honan 1998, p. 387.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1991, p. 78.

- ↑ Rowse 1963, p. 453.

- ↑ Kinney 2012, p. 11.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1977, pp. 224–227.

- ↑ Holderness 2001, pp. 152–154.

- ↑ Schoenbaum 1977, pp. 306–307.

Bibliography

- Ackroyd, Peter (2006). Shakespeare: The Biography. Vintage Books. ISBN 074938655X. https://archive.org/details/shakespeare00pete.

- Baldwin, T. W. (1944). William Shakespere's Small Latine & Lesse Greeke. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. OCLC 654144828. http://durer.press.illinois.edu/baldwin/.

- Bate, Jonathan (1998). The Genius of Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512823-9. https://archive.org/details/geniusofshakespe0000bate.

- Bentley, Gerald Eades (1984). The Profession of Player in Shakespeare's Time, 1590–1642. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-06596-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=rKb_AwAAQBAJ.

- Boehrer, Bruce (2013). Environmental Degradation in Jacobean Drama. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139149976. ISBN 9781139149976.

- Bryson, Bill (2007). Shakespeare: The World as Stage. Eminent Lives. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-074022-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=CoF4pdd0a0UC.

- Chambers, E. K. (1930a). William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. https://archive.org/details/williamshakespea017475mbp/page/n8.

- Chambers, E. K. (1930b). William Shakespeare: A Study of Facts and Problems. 2. Oxford: Clarendon Press. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.80390/page/n5.

- Cressy, David (1975). Education in Tudor and Stuart England. New York: St Martin's Press. ISBN 0-7131-5817-4. OCLC 2148260.

- Ellis, David (2012). The Truth about William Shakespeare. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-74-864666-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=TYpvAAAAQBAJ.

- Greenblatt, Stephen (2005). Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare. Pimlico. ISBN 978-0712600989.

- Halliwell-Phillipps, James O. (1907). Outlines of the Life of Shakespeare. Longmans, Green, and Co.. https://books.google.com/books?id=qxw-AAAAYAAJ.

- Holderness, Graham (2001). Cultural Shakespeare: Essays in the Shakespeare Myth. Hertfordshire: University of Hertfordshire Press. ISBN 9781902806112.

- Holderness, Graham (2011). Nine Lives of William Shakespeare. London and New York: Continuum. ISBN 978-1-4411-5185-8.

- Honigmann, E. A. J. (1985). Shakespeare: The Lost Years. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-1743-2. https://archive.org/details/shakespearelosty0000honi.

- Honan, Park (1998). Shakespeare: A Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-811792-2. https://archive.org/details/shakespearelife00hona/mode/2up.

- Ingram, William (2000). "Players and Playing, Introduction". in Wickham, Glynne; Berry, Herbert; Ingram, William. English Professional Theatre, 1530-1660. Theatre in Europe: A Documentary History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 155. ISBN 0-521-23012-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=y82YJ1P5gksC.

- Kinney, Arthur F. (2012). "Introduction". in Kinney, Arthur F.. The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare. Oxford Handbooks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–13. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199566105.013.0001. ISBN 9780199566105.

- Loomis, Catherine, ed (2002). William Shakespeare: A Documentary Volume. Dictionary of Literary Biography. 263. Detroit: Gale Group. ISBN 978-0-7876-6007-9. https://archive.org/details/williamshakespea0000unse_r6u9.

- Neilson, William; Thorndike, Ashley Horace (1915). The Facts about Shakespeare. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 358453.

- Palmer, Alan; Palmer, Veronica (1999). Who's Who in Shakespeare's England: Over 700 Concise Biographies of Shakespeare's Contemporaries. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780312220860.

- Pierce, Patricia (2006). "Shakespeare and the Forgotten Heroes". History Today 56 (7). https://www.historytoday.com/patricia-pierce/shakespeare-and-forgotten-heroes.

- Pogue, Kate (2006). Shakespeare's Friends. Greenwood Publishing. ISBN 9780275989569. https://archive.org/details/shakespearesfrie00pogu_0.

- Potter, Lois (2012). The Life of William Shakespeare: A Critical Biography. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20784-9.

- Rowse, A. L. (1963). William Shakespeare: A Biography. New York and Evanston: Harper & Row. https://archive.org/details/williamshakespea00rows.

- Schoenbaum, S. (1977). William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-502211-4. https://archive.org/details/williamshakespea00scho.

- Schoenbaum, S. (1979). Shakespeare: The Globe & the World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502645-4. https://archive.org/details/shakespeareglobe00scho.

- Schoenbaum, S. (1987). William Shakespeare: A Compact Documentary Life (Revised ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-505161-2.

- Schoenbaum, S. (1991). Shakespeare's Lives (Revised ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-818618-5. https://archive.org/details/shakespeareslive00scho_0.

- Schoone-Jongen, Terence (2008). Shakespeare's Companies: William Shakespeare's Early Career and the Acting Companies, 1577-1594. Studies in Performance and Early Modern Drama. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-6434-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=WbhRwG1MR_cC.

- Southworth, John (2000). Shakespeare the Player: A Life in the Theatre. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-7509-2312-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=Ta8TDQAAQBAJ.

- Spurgeon, Caroline (2004). Shakespeare's Imagery and What It Tells Us. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-06538-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=suW8WAhVnNQC.

- Wells, Stanley (1997). Shakespeare: A Life in Drama. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-31562-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=IRR8GlXh-vUC.

Further reading

- Honan, Park (2015). Dobson, Michael; Wells, Stanley; Sharpe, Will et al.. eds. The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780198708735.001.0001. ISBN 9780191788802.

External links

- Shakespeare Documented an online exhibition documenting Shakespeare in his own time.

- The Internet Shakespeare Editions provides an extensive section on his life and times.

- The Shakespeare Resource Center A directory of Web resources for online Shakespearean study. Includes a Shakespeare biography, works timeline, play synopses, and language resources.

- Documenting the Early Years and Documenting the Later Years are two interactive articles written by Michael Wood.

|