Social:Market power

| Competition law |

|---|

|

| Basic concepts |

| Anti-competitive practices |

| Enforcement authorities and organizations |

In economics, market power refers to the ability of a firm to influence the price at which it sells a product or service to increase economic profit.[1] In other words, market power occurs if a firm does not face a perfectly elastic demand curve and can set its price (P) above marginal cost (MC) without losing sales.[2] This indicates that the magnitude of market power is associated with the gap between P and MC at a firm's profit maximising level of output. Such propensities contradict perfectly competitive markets, where market participants have no market power, P = MC and firms earn zero economic profit.[3] Market participants in perfectly competitive markets are consequently referred to as 'price takers', whereas market participants that exhibit market power are referred to as 'price makers' or 'price setters'.

A firm with market power has the ability to individually affect either the total quantity or price in the market. This said, market power has been seen to exert more upward pressure on prices due to effects relating to Nash equilibria and profitable deviations that can be made by raising prices.[4] Price makers face a downward-sloping demand curve and as a result, price increases lead to a lower quantity demanded. The decrease in supply creates an economic deadweight loss (DWL) and a decline in consumer surplus.[5] This is viewed as socially undesirable and has implications for welfare and resource allocation as larger firms with high markups negatively effect labour markets by providing lower wages.[5] Perfectly competitive markets do not exhibit such issues as firms set prices that reflect costs, which is to the benefit of the customer. As a result, many countries have antitrust or other legislation intended to limit the ability of firms to accrue market power. Such legislation often regulates mergers and sometimes introduces a judicial power to compel divestiture.

Market power provides firms with the ability to engage in unilateral anti-competitive behavior.[6] As a result, legislation recognises that firms with market power can, in some circumstances, damage the competitive process. In particular, firms with market power are accused of limit pricing, predatory pricing, holding excess capacity and strategic bundling.[7] A firm usually has market power by having a high market share although this alone is not sufficient to establish the possession of significant market power. This is because highly concentrated markets may be contestable if there are no barriers to entry or exit. Invariably, this limits the incumbent firm's ability to raise its price above competitive levels.

If no individual participant in the market has significant market power, anti-competitive conduct can only take place through collusion, or the exercise of a group of participants' collective market power.[4] An example of which was seen in 2007, when British Airways was found to have colluded with Virgin Atlantic between 2004 and 2006, increasing their surcharges per ticket from £5 to £60.[8]

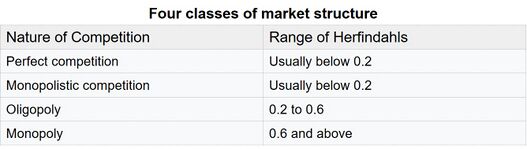

Regulators are able to assess the level of market power and dominance a firm has and measure competition through the use of several tools and indicators. Although market power is extremely difficult to measure, through the use of widely used analytical techniques such as concentration ratios, the Herfindahl-Hirschman index and the Lerner index, regulators are able to oversee and attempt to restore market competitiveness.[9]

Market Structure

In economics, market structure depicts how different industries are characterized and differentiated based upon the types of goods the firms sell (homogenous/heterogenous) and the nature of competition within the industry.[10] The degree of market power firms assert in different markets are relative to the market structure that the firms operate in. There are four main forms of market structures that are observed: perfect competition, monopolistic competition, oligopoly, and monopoly.[10]

Perfect competition power

The concept of perfect competition represents a theoretical market structure where the market reaches an equilibrium that is Pareto optimal. This occurs when the quantity supplied by sellers in the market equals the quantity demanded by buyers in the market at the current price.[11] Firms competing in a perfectly competitive market faces a market price that is equal to their marginal cost, therefore, no economic profits are present. The following criteria need to be satisfied in a perfectly competitive market:

- Producers sell homogenous goods

- All firms are price takers

- Perfect information

- No barriers to enter and exit

- All firms have relatively small market share and cannot influence price

As all firms in the market are price takers, they essentially hold zero market power. A perfectly competitive market is logically impossible to achieve in a real world scenario as it embodies contradiction in itself and therefore is considered an idealised framework by economists.[12]

Monopolistic competition power

Monopolistic competition can be described as the "middle ground" between perfect competition and a monopoly as it shares elements present in both market structures that are on different ends of the market structure spectrum.[13] Monopolistic competition is a type of market structure defined by many producers that are competing against each other by selling similar goods which are differentiated, thus are not perfect substitutes.[14] In the short term, firms are able to obtain economic profits as a result of differentiated goods providing sellers with some degree of market power; however, profits approaches zero as more competitive toughness increases in the industry.[15] The main characteristics of monopolistic competition include:

- Differentiated products

- Many sellers and buyers

- Free entry and exit

Firms within this market structure are not price takers and compete based on product price, quality and through marketing efforts.[16] Examples of industries with monopolistic competition include restaurants, hairdressers and clothing.

Monopoly power

The word monopoly is used in various instances referring to a single seller of a product, a producer with an overwhelming level of market share, or refer to a large firm.[17] All of these treatments have one unifying factor which is the ability to influence the market price by altering the supply of the good or service through its own production decisions. The most discussed form of market power is that of a monopoly, but other forms such as monopsony and more moderate versions of these extremes exist. A monopoly is considered a 'market failure' and consists of one firm that produces a unique product or service without close substitutes. Whilst pure monopolies are rare, monopoly power is far more common and can be seen in many industries even with more than one supplier in the market.[18] Firms with monopoly power can charge a higher price for products (higher markup) as demand is relatively inelastic.[19] They also see a falling rate of labour share as firms divest from expensive inputs such as labour.[20] Often, firms with monopoly power exist in industries with high barriers to entry, which include, but are not limited to:

- Economies of scale

- Predatory pricing[18]

- Control of key resources (required in production of the good)

- Legal regulations[19]

A well-known example of monopolistic market power is Microsoft's market share in PC operating systems. The United States v. Microsoft case dealt with an allegation that Microsoft illegally exercised its market power by bundling its web browser with its operating system. In this respect, the notion of dominance and dominant position in EU Antitrust Law is a strictly related aspect.[21]

Oligopoly power

Another form of market power is that of an oligopoly or oligopsony. Within this market structure, the market is highly concentrated and several firms control a significant share of market sales.[22] The main characteristics of an oligopoly are:

- A few sellers and many buyers.

- Homogenous or differentiated products.

- Barriers to entry. This includes, but is not limited to, 'technology challenges, government regulations, patents, start-up costs, or education and licensing requirements'.[23]

- Interaction/strategic behaviour.

It is salient to note that only a few firms make up the market share. Hence, their market power is large as a collective and each firm has little or no market power independently.[24] Generally, when a firm operating in an oligopolistic market adjusts prices, other firms in the industry will be directly impacted.

The graph below depicts the kinked demand curve hypothesis which was proposed by Paul Sweezy who was an American economist.[25] It is important to note that this graph is a simplistic example of a kinked demand curve.

Oligopolistic firms are believed to operate within the confines of the kinked demand function. This means that when firms set prices above the prevailing price level (P*), prices are relatively elastic because individuals are likely to switch to a competitor's product as a substitute. Prices below P* are believed to be relatively inelastic as competitive firms are likely to mimic the change in prices, meaning less gains are experienced by the firm.[26]

An oligopoly may engage in collusion, either tacit or overt to exercise market power. A group of firms that explicitly agree to affect market price or output is called a cartel, with the organization of petroleum-exporting countries (OPEC) being one of the most well known example of an international cartel.

Sources of market power

By remaining consistent with the strict definition of market power as any firm with a positive Lerner index, the sources of market power is derived from distinctiveness of the good and or seller.[27] For a monopolist, distinctiveness is a necessary condition that needs to be satisfied but this is just the starting point. Without barriers to entries, above normal profits experienced by monopolists would not persist as other sellers of homogenous or similar goods would continue to enter the industry until above normal profits are diminished until the industry experiences perfect competition[27]

There are several sources of market power including:

- High barriers to entry. These barriers include the control of scarce resources, increasing returns to scale, technological superiority and government created barriers to entry.[28] OPEC is an example of an organization that has market power due to control over scarce resources — oil.

- Increasing returns to scale. Firms that experience increasing returns to scale also experience decreasing average total costs and therefore become more profitable with size.[28]

- High start-up costs. This barrier makes it difficult for new entrants to succeed. Firms like power, cable television and telecommunication companies fall within this category. A firm seeking to enter such industries require the ability to spend millions of dollars before starting operations and generating revenue.

- Brand loyalty of consumers and value placed by consumers on reputation. Incumbent firms often have a competitive advantage over new entrants. An incumbent firm can engage in several entry-deterring strategies such as limit pricing, predatory pricing and strategic bundling. Microsoft has substantial pricing or market power due to technological superiority in its design and production processes.[28]

- Government policies/regulations. A prime example are patents granted to pharmaceutical companies. These patents give the drug companies a virtual monopoly in the protected product for the term of the patent.

Measurement of market power

Measuring market power is inherently complex because the most widely used measures are sensitive to the definition of a market.

Magnitude of a firm's market power is shown by a firm's ability to deviate from an elastic demand curve and charge a higher price (P) above its marginal cost (C), commonly referred to as a firm's mark-up or margin.[29] The higher a firm's mark-up, the larger the magnitude of power. This said, markups are complicated to measure as they are reliant on a firm's marginal costs and as a result, concentration ratios are the more common measures as they require only publicly accessible revenue data.

Concentration ratios

Market concentration, also referred to as industry concentration, refers to the extent of which market shares of the largest firms in the market account for a significant portion of the economic activities quantifiable by various metrics such as sales, employment, active users.[30] Recent macroeconomic market power literature indicates that concentration rations are the most frequently used measure of market power.[2] Measures of concentration summarise the share of market or industry activity accounted for by large firms. An advantage of using concentration as an empirical tool to quantify market power is the requirement of only needing revenue data of firms which results in the corresponding disadvantage of the inconsideration of costs or profits.[29]

N-firm concentration ratio

The N-firm concentration ratio gives the combined market share of the largest N firms in the market. For example, a 4-firm concentration ratio measures the total market share of the four largest firms in an industry. In order to calculate the N-firm concentration ratio, one usually uses sales revenue to calculate market share, however, concentration ratios based on other measures such as production capacity may also be used. For a monopoly, the 4-firm concentration ratio is 100 per cent whilst for perfect competition, the ratio is zero.[31] Moreover, studies indicate that a concentration ratio of between 40 and 70 percent suggests that the firm operates as an oligopoly.[32] These figures are viable but should be used as a 'rule of thumb' as it is important to consider other market factors when analysing concentration ratios.

An advantage of concentration ratios as an empirical tool for studying market power is that it requires only data on revenues and is thus easy to compute. The corresponding disadvantage is that concentration is about relative revenue and includes no information about costs or profits.

Herfindahl-Hirschman index

The Herfindahl-Hirschman index (HHI) is another measure of concentration and is the sum of the squared market shares of all firms in a market.[33] For example, in a market with two firms, each with 50% market share, the HHI equals = 0.502 + 0.502 = 0.50. The HHI for a monopoly is 1 whilst for perfect competition, the HHI is zero. Unlike the N-firm concentration ratio, large firms are given more weight in the HHI and as a result, the HHI conveys more information. However the HHI has its own limitations as it is sensitive to the definition of a market, therefore meaning you cannot use it to cross-examine different industries, or do analysis over time as the industry changes.[20]

Lerner index

The Lerner index is a widely accepted and applied method of estimating market power in a monopoly. It compares a firm's price of output with its associated marginal cost where marginal cost pricing is the "socially optimal level" achieved in market with perfect competition.[34] Lerner (1934) believes that market power is the monopoly manufacturers' ability to raise prices above their marginal cost.[35] This notion can be expressed by using the formula:

Where P represents the price of the good set by the firm and MC representing the firm's marginal cost.The formula focuses on the nature of monopoly and emphasising welfare economic implications of the Pareto optimal principle.[36] Although Lerner is usually credited for the price/cost margin index, the generalized version was fully derived prior to WWII by Italian neoclassical economist, Luigi Amaroso.[37]

Elasticity of demand

The degree to which a firm can raise its price above marginal cost depends on the shape of the demand curve at a firm's profit maximising level of output.[38] Consequently, the relationship between market power and the price elasticity of demand (PED) can be summarised by the equation:

The ratio P/MC is always greater than 1 and the higher the P/MC ratio, the more market power the firm possesses. As PED increases in magnitude, the P/MC ratio approaches 1 and market power approaches zero. The equation is derived from the monopolist pricing rule:

Nobel Memorial Prize

Jean Tirole was awarded the 2014 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his analysis of market power and economic regulation.[39]

See also

- Bargaining power

- Imperfect competition

- Market concentration

- Natural monopoly

- Predatory pricing

- Price discrimination

- Dominance (economics)

References

- ↑ Landes, M. & Posner, R. (1981). Market Power in Antitrust Cases. Harvard Law Review, (94)5, 937-996. https://doi.org/10.2307/1340687

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Syverson, C. (2019). Macroeconomics and Market Power. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 33(3), 23-43. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.33.3.23

- ↑ Pleatsikas, C. (2018) Perfect Competition. In: Augier, M & Teece, D. (eds) The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Strategic Management. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-00772-8_558

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Davis, D. (2018). Market Power and Collusion in Laboratory Markets. In The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics (pp. 8260–8263). Palgrave Macmillan UK. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_2836

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 De Loecker, J., Eeckhout, J., & Unger, G. (2020). THE RISE OF MARKET POWER AND THE MACROECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135(2), 561-644. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz041

- ↑ Vatiero, M. (2010). The Ordoliberal Notion of Market Power: An Institutionalist Reassessment. European Competition Journal, 6(3), 689–707. https://doi.org/10.5235/ecj.v6n3.689

- ↑ Leslie, C. (2013). PREDATORY PRICING AND RECOUPMENT. Columbia Law Review, 113(7), 1695–1771.

- ↑ Lin, Jing; Ma, Xin; Talluri, Srinivas; Yang, Cheng-Hu (2021-02-09). "Retail channel management decisions under collusion" (in en). European Journal of Operational Research 294 (2): 700–710. doi:10.1016/j.ejor.2021.01.046. ISSN 0377-2217. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S037722172100076X.

- ↑ Borenstein, Severin; Bushnell, James; Knittel, Christopher R. (1999). "Market Power in Electricity Markets: Beyond Concentration Measures". The Energy Journal 20 (4): 65–88. doi:10.5547/ISSN0195-6574-EJ-Vol20-No4-3. ISSN 0195-6574. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41326187.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Lábaj, Martin; Morvay, Karol; Silanič, Peter; Weiss, Christoph; Yontcheva, Biliana (2018-03-28). "Market structure and competition in transition: results from a spatial analysis" (in en). Applied Economics 50 (15): 1694–1715. doi:10.1080/00036846.2017.1374535. ISSN 0003-6846.

- ↑ Debreu, Gerard (1959). Theory of value; an axiomatic analysis of economic equilibrium. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-01558-5. OCLC 420976.

- ↑ McDermott, John F. M. (2015-05-19). "Perfect competition, methodologically contemplated". Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 37 (4): 687–703. doi:10.1080/01603477.2015.1050335. ISSN 0160-3477.

- ↑ Barkley, Andrew (2016). The Economics of Food and Agricultural Markets. Minneapolis, MN. ISBN 978-1-944548-22-3. OCLC 1151088067.

- ↑ Krugman, Paul R.; Maurice Obstfeld (2009). International economics: theory and policy (8th ed.). Boston: Pearson Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-49304-0. OCLC 174112719.

- ↑ d’Aspremont, Claude; Dos Santos Ferreira, Rodolphe (June 2016). "Oligopolistic vs. monopolistic competition: Do intersectoral effects matter?" (in en). Economic Theory 62 (1–2): 299–324. doi:10.1007/s00199-015-0905-8. ISSN 0938-2259. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00199-015-0905-8.

- ↑ "Monopolistic Competition - Overview, How It Works, Limitations" (in en-US). https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/economics/monopolistic-competition-2/.

- ↑ McKenzie, Richard B.; Lee, Dwight R. (2008), "Deadweight-Loss Monopoly", In Defense of Monopoly, How Market Power Fosters Creative Production (University of Michigan Press): pp. 25–53, ISBN 978-0-472-11615-7, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvnjbdsg.5, retrieved 2021-04-25

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 "Monopoly power as a market failure | Economics Online | Economics Online" (in en-US). 2020-01-29. https://www.economicsonline.co.uk/Market_failures/Monopoly_power.html.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Monopoly Power" (in en). https://xplaind.com/327596/monopoly-power.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 De Loecker, Jan; Eeckhout, Jan; Unger, Gabriel (2020-05-01). "The Rise of Market Power and the Macroeconomic Implications*". The Quarterly Journal of Economics 135 (2): 561–644. doi:10.1093/qje/qjz041. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ↑ Vatiero, M. (2009). An Institutionalist Explanation of Market Dominances. World Competition. Law and Economics Review, 32(2):221–226.

- ↑ "Oligopoly - characteristics | Economics Online | Economics Online" (in en-US). 2020-01-20. https://www.economicsonline.co.uk/Business_economics/Oligopoly.html.

- ↑ "Barriers to Entry - Types of Barriers to Markets & How They Work" (in en-US). https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/economics/barriers-to-entry/.

- ↑ "Section 3: Characteristics of an Oligopoly Industry | Inflate Your Mind" (in en-US). https://inflateyourmind.com/microeconomics/unit-8-microeconomics/section-3-characteristics-of-an-oligopoly-industry/.

- ↑ "Kinked Demand Curve". https://www.toppr.com/guides/business-economics/determination-of-prices/kinked-demand-curve/.

- ↑ "Interdependence in Oligopolies | Revision World". https://revisionworld.com/a2-level-level-revision/economics-level-revision/business-economics-distribution-income/concentrated-markets/interdependence-oligopolies.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 White, Lawrence J. (2013-07-01), Thomas, Christopher R.; Shughart, William F., eds., "Market Power: How Does it Arise? How is it Measured?" (in en), The Oxford Handbook of Managerial Economics (Oxford University Press): pp. 30–65, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199782956.013.0003, ISBN 978-0-19-978295-6, http://oxfordhandbooks.com/view/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199782956.001.0001/oxfordhb-9780199782956-e-003, retrieved 2021-04-25

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Krugman & Wells, Microeconomics 2d ed. (Worth 2009)

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Syverson, Chad (2019-08-01). "Macroeconomics and Market Power: Context, Implications, and Open Questions" (in en). Journal of Economic Perspectives 33 (3): 23–43. doi:10.1257/jep.33.3.23. ISSN 0895-3309.

- ↑ Kvålseth, Tarald O. (2018-10-11). "Relationship between concentration ratio and Herfindahl-Hirschman index: A re-examination based on majorization theory". Heliyon 4 (10): e00846. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00846. ISSN 2405-8440. PMID 30338305.

- ↑ Samuelson & Nordhaus, Microeconomics, 17th ed. (McGraw-Hill 2001) at 183.

- ↑ "Glossary: Learn more about IBISWorld's key terms". 2018-12-08. https://www.ibisworld.com/about/glossary/.

- ↑ Samuelson & Nordhaus, Microeconomics, 17th ed. (McGraw-Hill 2001) at 184.

- ↑ Spierdijk, Laura; Zaouras, Michalis (2017-09-02). "The Lerner index and revenue maximization". Applied Economics Letters 24 (15): 1075–1079. doi:10.1080/13504851.2016.1254333. ISSN 1350-4851.

- ↑ Sun, B., Jing, W., Zhao, X, & He, Y. (2017). Research on market power and market structure. International Journal of Crowd Science, 1(3), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCS-08-2017-0009

- ↑ Elzinga, K. & Mills, D. (2011). The Lerner Index of Monopoly Power: Origins and Uses. The American Economic Review, 101(3), 558–564. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.3.558

- ↑ Giocoli, Nicola (2012). "Who Invented the Lerner Index? Luigi Amoroso, the Dominant Firm Model, and the Measurement of Market Power". Review of Industrial Organization 41 (3): 181–191. doi:10.1007/s11151-012-9355-7. ISSN 0889-938X. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43550398.

- ↑ Perloff, J: Microeconomics Theory & Applications with Calculus page 369. Pearson 2008.

- ↑ "The Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel 2014" (in en-US). https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2014/press-release/.

Further references

- Syverson, Chad. 2019. "Macroeconomics and Market Power: Context, Implications, and Open Questions." Journal of Economic Perspectives 33(3): 23-43.

- Brickley, Smith and Zimmerman (13 October 2008). "7". Managerial Economics and Organizational Architecture (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0073375823.

- "The Theory of Industrial Organization", Tirole, MIT Press 1988