Social:Optimates

Optimates | |

|---|---|

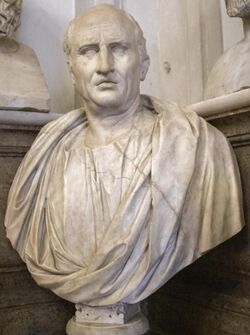

| Main leaders | Cato the Younger Lucius Cornelius Sulla Marcus Licinius Crassus Marcus Tullius Cicero |

| Ideology | Conservatism |

The optimates (/ˈɒptɪməts/; Latin for "best ones", singular: optimas), also known as boni ("good men"), are a label in studies of the late Roman republic. They are seen as supporters of the continued authority of the senate.[1][2]

The importance of the term comes from Cicero's Pro Sestio, a speech published in 56 BC,[3][4] in which he constructs two types of politicians.

Meaning

Cicero's use of the term, that "optimates [aim] to gain the approval of the best people", is recognised to be polemical.[5] The modern understanding of the term is that it is in contrast to populares and that for a person to be popularis.

There were themes of popularis ideological causes, which the optimates opposed: secret ballot, subsidised grain, and inclusion of non-senators on juries before the law courts.[1]

Popularis rhetoric drew on historical precedents (exempla) – including that from ancient times, such as the revival of the comitia Centuriata as a popular law court,[6] – from the abolition of the Roman monarchy to the popular rights and liberties won by the succession of the plebs.[1] T. P. Wiseman argues that these differences reflected 'rival ideologies' with 'mutually incompatible [views on] what the republic was'.[7] Optimates and populares agreed, however, on core values such as Roman liberty and the sacred nature of the republic.[1][8] They disagreed, however, as to the extent of the senate's legitimacy and the sovereign powers of the popular assemblies.[9] Optimates stood against the ideological power of the populares to transfer powers from the senate to the popular assemblies.[10]

to adopt a certain method of political working, to use the populace, rather than the senate, as a means to an end; the end being, most likely, personal advantage for the politician concerned.[11]

This political method involved a populist style of rhetoric, and 'only to a limited extent, that of policy' with even less ideological content.[1][12]

Historiography

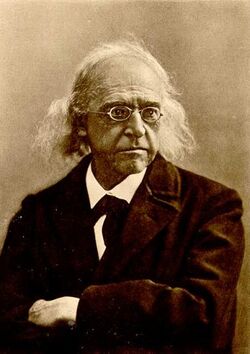

The traditional view comes from scholarship by Theodor Mommsen during the 19th century, in which he identified both populares and optimates as 'parliamentary-style political parties' in a modern sense, suggesting that the struggle of the orders resulted in the formation of an aristocratic and a democratic party.[13] John Edwin Sandys, writing in 1921 in this traditional scholarship, identifies the optimates as the killers of Tiberius Gracchus in 133 BC.[14] Mommsen too suggested that the labels themselves became common in Gracchan times.[15]

There has been a substantial shift in views on Roman politics since the early 20th century. The traditional view, that there was a persistent faction of optimates who opposed populares is no longer accepted. Yakobson, in the Oxford Classical Dictionary writes:

It is, and has been for a long time, commonplace to point out that the late-Republican populares and optimates were not political parties in anything like the modern sense. This is often said while distancing oneself from Mommsen’s analysis of late-Republican politics in terms of a party conflict between populares and optimates. Certainly, there was no “popular party” or “optimate party” in Rome, complete with the usual hallmarks of modern organized party politics such as formal structure, membership or leadership, written programs and manifestoes. Nor—crucially because of the vital importance of elected officials in the Republic—did candidates run for office sponsored by a “party” and wearing a party label and they were certainly not supposed to govern in the name of a party.[1]

In modern classics scholarship, the optimates are not recognised as members of a political party "in anything like the modern sense", contra older scholarship such as "Mommsen’s analysis of late-Republican politics in terms of a party conflict between populares and optimates".[1][lower-alpha 1] Politicians in ancient Rome did not stand for office on party lines or govern under party labels; politicians generally acted alone or in small ad hoc alliances.[1] There were no "neat categories of optimates and populares" or of conservatives and radicals in a modern sense.[16]

Many scholars question the extent to which Pro Se reflected actual republican politics. Robb argues that Cicero's description of the categories is greatly distorted.[17] The term was not used in an entirely political sense: Cicero, while linking optimates to Greek aristokratia (ἀριστοκρατία), also used the word populares to describe politics 'completely compatible with... honourable aristocratic behaviour'.[18]

Rather, according to Syme in the classic 1939 book Roman Revolution:

The political life of the Roman Republic was stamped and swayed, not by parties and programmes of a modern and parliamentary character, not by the ostensible opposition between senate and people, optimates and populares, nobiles and novi homines, but by the strife for power, wealth and glory. The contestants were the nobiles among themselves, as individuals or in groups, open in the elections and in the courts of law, or masked by secret intrigue.[19]

Syme's description of Roman politics viewed the late republic 'as a conflict between a dominant oligarchy drawn from a set of powerful families and their opponents'.[20] Strausberger, writing also in 1939, challenged the traditional view of political parties, arguing that 'there was no "class war"' in the various civil wars (Sulla's civil war and Caesar's civil war) that concluded the republic.[21]

Erich S. Gruen in the famous The Last Generation of the Roman Republic (1974) rejected the terms entirely:

The term optimates identified no political group. Cicero, in fact, could stretch the term to encompass not only aristocratic leaders but also Italians, [farmers], businessmen, and even freedmen. His criteria demanded only that they be honest, reasonable, and stable. It was no more than a means of expressing approbation. Romans would have had even greater difficulty in comprehending the phrase 'senatorial party'... The phrase originates in an older scholarship which misapplied analogies and reduced Roman politics to a contest between the 'senatorial party' and the 'popular party'. Such labels obscure rather than enlighten.[22]

Brunt, writing in the 1980s–90s, emphasised that "shifting alliances and loyalties between senators precluded the existence of durable or cohesive groups which could be identified as optimates or populares".[23] And that the transitory nature of political alliances made differences between factions or groups 'far less significant' than 'conflicts of principle'.[23]

The optimates were explored by Burckhardt in 1988, viewing them as portions of the nobility acting against the tribunes of the plebs and focusing on vetoes and obstructionist tactics. Gruen, however, noted in 1995, that this analysis provided 'no clear criteria' for determining anything about the makeup of the group.[24] Identification of optimates also continues to be difficult. They have been identified as "members of an 'aristocratic party' to upholders of senatorial authority to supporters of the class interests of the wealthy".[25]

Robert Morstein-Marx cautioned in 2004 against understanding the terms populares and optimates as solid factions or as ideological groupings:

It is important to realize that references to populares in the plural do not imply a co-ordinated 'party' with a distinctive ideological character, a kind of political grouping for which there is no evidence in Rome, but simply allude to a recognizable, if statistically quite rare, type of senator whose activities are scattered sporadically across late-Republic history... The 'life-long' popularis... was a new and worrying phenomenon at the time of Julius Caesar's consulship of 59: an underlying reason why the man inspired such profound fears.[26]

The categories emerge from Cicero's writings and were 'far from corresponding with definite parties or definite policies'.[27] It also is damaging to the utility of the term that Roman politicians, including Caesar and Sallust, never identified Caesar as a member of any populares "faction".[27] 'The terms populares and optimates were not common and everyday labels used to categorise certain types of late republican politician'.[28]

There continues to be debate as to the utility of the terms in scholarship. In 1994, Andrew Lintott wrote in The Cambridge Ancient History that although both factions came from the same social class, there is 'no reason to deny the divergence of ideology highlighted by Cicero' with themes and leaders stretching back in Cicero's time for hundreds of years.[29] T. P. Wiseman, for example, lamented an 'ideological vacuum' in 2009, promoting the term as an label for ideology rather than for political factionalism in the vein of Mommsen.[30]

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Yakobson, Alexander (2016-03-07). "optimates, populares" (in en). doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.4578. https://oxfordre.com/classics/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.001.0001/acrefore-9780199381135-e-4578.

- ↑ Robb 2010, p. 96.

- ↑ Robb 2010, p. 11.

- ↑ Robb 2010, p. 42.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Mackie 1992, p. 49.

- ↑ Mackie 1992, p. 58.

- ↑ Wiseman 2008, p. 18.

- ↑ Mackie 1992, pp. 54–5.

- ↑ Mackie 1992, pp. 56–7.

- ↑ Mackie 1992, p. 62.

- ↑ Mackie 1992, p. 50.

- ↑ Gruen 1974, p. 384. "There was no fundamental ideological cleavage between optimates and populares". Footnote 104.

- ↑ Robb 2010, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Sandys, John Edwin (1921). A Companion to Latin Studies (3 ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 125. https://books.google.com/books?id=XV1oAAAAMAAJ. "133[:] Tribute of Ti. Gracchus, his 'lex agraria' and destruction by a rabble of optimates, headed by P. Scipio Nasica [...]".

- ↑ Robb 2010, p. 16.

- ↑ Gruen 1974, p. 500.

- ↑ Robb 2010, p. 35.

- ↑ Robb 2010, p. 99.

- ↑ Syme 1939, p. 11.

- ↑ Robb 2010, p. 19.

- ↑ Robb 2010, p. 20.

- ↑ Gruen 1974, p. 50.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Robb 2010, p. 25.

- ↑ Robb 2010, p. 27.

- ↑ Robb 2010, p. 32.

- ↑ Morstein-Marx, Robert (5 February 2004). Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511482878. ISBN 9781139449878. https://books.google.com/books?id=55sbCxI_iVYC&pg=PA204.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Robb 2010, p. 33.

- ↑ Robb 2010, p. 167.

- ↑ Lintott, Andrew (1994). "Political History, 146–96 BC}". in Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen (in en). The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-521-25603-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=3yUkzNLiY4oC&pg=RA1-PA52.

- ↑ Wiseman 2008, pp. 6–7.

Books

- Gruen, Erich S. (1974) (in en). The Last Generation of the Roman Republic. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-02238-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=joedtN6nKXQC.

- Robb, M. A. (2010) (in en). Beyond Populares and Optimates: Political Language in the Late Republic. Steiner. ISBN 978-3-515-09643-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=gf_IbwAACAAJ&newbks=0&hl=en.

- Syme, Ronald (1939) (in English). The Roman revolution,. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. OCLC 830891947. https://www.worldcat.org/title/roman-revolution/oclc/830891947.

- Wiseman, T. P. (2008-12-25). "Roman History and the Ideological Vacuum" (in en). Remembering the Roman People: Essays on Late-Republican Politics and Literature. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-156750-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=GFx-WN64xSQC.

Articles

- Mackie, Nicola (1992). ""Popularis" ideology and popular politics at Rome in the first century BC". Rheinisches Museum für Philologie 135 (1): 49. ISSN 0035-449X. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41233843.