Social:Révolution nationale

The Révolution nationale (French pronunciation: [ʁevɔlysjɔ̃ nɑsjɔnal], National Revolution) was the official ideological program promoted by the Vichy regime (the “French State”) which had been established in July 1940 and led by Marshal Philippe Pétain. Pétain's regime was characterized by anti-parliamentarism, personality cultism, xenophobia, state-sponsored anti-Semitism, promotion of traditional values, rejection of the constitutional separation of powers, modernity, and corporatism, as well as opposition to the theory of class conflict. Despite its name, the ideological policies were reactionary rather than revolutionary as the program opposed almost every change introduced to French society by the French Revolution .[1]

As soon as it was established, Pétain's government took measures against the “undesirables”, namely Jews, métèques (foreigners), Freemasons, and Communists. The persecution of these four groups was inspired by Charles Maurras’ concept of the "Anti-France", or "internal foreigners", which he defined as the "four confederate states of Protestants, Jews, Freemasons and foreigners".[citation needed] The regime also persecuted Romani people, homosexuals, and left-wing activists in general. Vichy imitated the racial policies of the Third Reich and also engaged in natalist policies aimed at reviving the "French race" (including a sports policy), although these policies never went as far as Nazi eugenics.

Ideology

The ideology of the French State (Vichy France) was an adaptation of the ideas of the French far-right (including monarchism and Charles Maurras’ integralism) by a crisis government that was a client state, born out of the defeat of France against Nazi Germany. It included:

- The conflation of legislative and executive powers: the Constitutional Acts[2] drafted by Marshal Pétain on 11 July 1940 gave to him "more powers than to Louis XIV" (according to a quote by Pétain himself, brought by his civil head of staff, H. Du Moulin de Labarthète), including that of drafting a new Constitution.

- Anti-parliamentarism and rejection of the multi-party system.

- Personality cultism: Marshal Pétain's portrait was omnipresent, printed on money, stamps, walls or represented in sculptures. A song to his glory, Maréchal, nous voilà !, became the unofficial national anthem. Obedience to the leader and to the hierarchy was exalted.

- Corporatism, with the establishment of a Labour Charter (suppression of trade-unions replaced by corporations organized by profession, suppression of the right to strike).

- Stigmatization of those seen as responsible for the military defeat, expressed in particular during the Riom Trial (1942–43): the Third Republic, in particular the Popular Front (despite the fact that Léon Blum’s left-wing government prepared France for the war by launching a new military effort), Communists, Jews, etc. The defendants of the Riom Trial included Blum, Édouard Daladier, Paul Reynaud, Georges Mandel and Maurice Gamelin: they were largely successful in rebutting the charges, and won sympathetic coverage in the international press, leading to the suspension of the trial in 1942 and its closure in 1943.

- State-sponsored anti-Semitism. Jews, national or not, were excluded from the Nation, and prohibited from working in public services. The first law on the status of Jews was promulgated on 3 October 1940. Thousands of naturalized Jews were deprived of their citizenship, while all Jews were forced to wear a yellow badge. The next day, Pétain signed another edict, this one authorizing detainment of foreign Jews in France. The Crémieux Decree of 1870 was abrogated on 7 October by Interior Minister Marcel Peyrouton, stripping Algerian Jews of their French citizenship as well. A numerus clausus drastically limited their presence at the University, among physicians, lawyers, filmmakers, bankers or small traders. Soon the list of off-limits works was greatly increased. In less than a year, more than half of the Jewish population in France was deprived of any means of subsistence.[3] Foreign Jews first, then all Jews were at first detained in concentration camps in France, before being deported to Drancy internment camp where they were then sent to Nazi concentration camps.

- “Organicism” and rejection of class conflict.

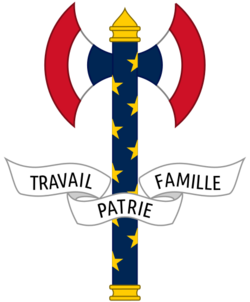

- Promotion of traditional values. The Republican motto of “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité” was replaced by the populist motto of “Labour, Family, Fatherland” (Travail, Famille, Patrie).

- Clericalism and promotion of traditional Catholic values. Catholic social teaching of the time, particularly the encyclical Quadragesimo anno of Pope Pius XI, was influential in the Vichy regime, which was also active in defending traditional Catholic values, eulogising national religious figures such as Joan d'Arc and restoring some privileges of the clergy that had been abolished by the 1905 law on the Separation of the Churches and the State, though the law was never fully repealed and Catholicism was not reinstated as a state religion. The Catholic Church in France welcomed these changes and expressed a certain degree of support towards the regime until 1944, although the Church was also strongly critical of some Vichy policies, such as the deportation of the Jews and institutional racism. However, a consistent number of Catholics took part in the French Resistance with the support of some segments of the clergy, among whom Georges Bidault, who later became the founder of the Popular Republican Movement.[4]

- Rejection of cultural modernism and of intellectual and urban elites. Policy of “return to the earth”.[5]

None of these changes were forced on France by Germany. The Vichy government instituted them voluntarily as part of the National Revolution,[6] while Germany interfered little in internal French affairs for the first two years after the armistice as long as public order was maintained. It was suspicious of the aspects of the National Revolution that encouraged French patriotism, and banned Vichy veteran and youth groups from the Occupied Zone.[7]

Support

Pierre Laval, speaking during his trial in 1945.[8]

The Révolution nationale was never fully defined by the Vichy regime although it was frequently invoked by its most enthusiastic supporters. Philippe Pétain himself was rumoured to dislike the term and only used it four times in his wartime speeches.[8] As a result, different factions formed different views of what it meant which conformed with their own ideological views about the regime and the postwar future.[8]

The Pétainistes gathered those who supported the personal figure of Marshal Pétain, considered at that time a war hero of the Battle of Verdun. The Collaborateurs include those who collaborated with Nazi Germany or advocated collaboration, but who are considered more moderate, or more opportunistic, than the Collaborationistes, advocates of a French fascism.

Supporters of collaboration were not necessarily supporters of the National Revolution, and vice versa. Pierre Laval was a collaborationist but was dubious about the National Revolution, while others like Maxime Weygand opposed collaboration but supported the National Revolution because they believed that reforming France would help it avenge its defeat.[7]

Those who supported the ideology of the National Revolution rather than the person of Pétain himself could be divided, in general, into three groups: the counter-revolutionary reactionaries; the supporters of a French fascism; and the reformers who saw in the new regime in opportunity to modernize the state apparatus. The last current would include opportunists such as the journalist Jean Luchaire who saw in the new regime career opportunities.

- The “Reactionaries”, in the strict sense of the word: all those who dreamt of a return to "before", either:

- before 1936 and the Popular Front

- before 1870 and the Third Republic or

- before 1789 and the French Revolution .

These were part of the counter-revolutionary branch of the French far right, the oldest one being composed of Legitimists, monarchist members of the Action française (AF), etc. But the Vichy regime also received support from large sectors of the liberal Orleanists, in particular from its mouthpiece, Le Temps newspaper.[9]

- The supporters of a “French fascism”, who attacked Vichy and Maurras for not seeking to bring Nazism to France.[7] They opposed specific traditionalist aspects such as clericalism or "naive scouting", but still thought the Révolution nationale prepared for a "re-birth" of French society. These formed the most stringent Collaborationists (collaborationistes, distinct from collaborateurs who are seen as more moderate or more opportunist). Those included the supporters of Marcel Déat's Rassemblement national populaire (RNP), Jacques Doriot's Parti Populaire Français (PPF), Joseph Darnand's Service d'ordre légionnaire (SOL) militia, Marcel Bucard's Mouvement Franciste (originally funded by Benito Mussolini), members of the Cagoule terrorist group, funded by Eugène Schueller (the founder of L'Oréal cosmetic group), the writers Robert Brasillach, Louis-Ferdinand Céline or Pierre Drieu La Rochelle, Philippe Henriot at Radio Paris, etc.

- The Reformers, who were looking for new political, social and economic policies, and formed an important group during the inter-war period. Those included the non-conformists of the 1930s, Christian-democrat personalists, neo-socialists, planistes, Young Turks of the Radical Socialist Party, technocrats (Groupe X-Crise), etc. All of these circles would also provide recruits to the Resistance. Most of them were not ideologically anti-democrats, but claimed to take advantage of the new conditions set by the Vichy regime—they also included plain opportunists willing to make a quick career. They presented various and contradictory solutions: communalism, cooperatives or corporations, "return to the earth", planned economy, technocracy rule, etc. Some examples include René Belin, Minister of Production and Labour, Lucien Romier, who also became Minister of Pétain, the civil servant Gérard Bardet, X-Crise member Pierre Pucheu, François Lehideux, Yves Bouthillier, Jacques Barnaud, or the École des cadres d'Uriage, which would form the basis after the war of the elite school École nationale d'administration (ENA).[citation needed]

The supporters were, however, in the minority. Although the Vichy government initially had substantial support from those who were glad that the war was over and expected that Britain would soon surrender, and Pétain remained personally popular during the war, by late autumn 1940 most French hoped for a British victory and opposed collaboration with Germany.[6]

Evolution of the regime

From July 1940 to 1942, the Révolution nationale was strongly promoted by the traditionalist and technocratic Vichy government. When in May 1942 Pierre Laval (a former socialist and republican) returned as the head of government, the Révolution nationale was no longer promoted but fell into oblivion and collaboration was emphasized.[citation needed]

Eugenics

In 1941, Nobel Prize winner Alexis Carrel, who had been an early proponent of eugenics and euthanasia and was a member of Jacques Doriot's French Popular Party (PPF), went on to advocate the creation of the French Foundation for the Study of Human Problems (Fondation Française pour l’Etude des Problèmes Humains), using connections to the Pétain cabinet (specifically, French industrial physicians André Gros and Jacques Ménétrier). Charged with the "study, under all of its aspects, of measures aimed at safeguarding, improving and developing the French population in all of its activities," the Foundation was created by decree of the Vichy regime in 1941, and Carrel appointed as “regent”.[10]

Sport policy

Vichy's policy concerning sports found its origins in the conception of Georges Hébert (1875–1957), who denounced professional and spectacular competition, and like Pierre de Coubertin, founder of the Olympic Games was a supporter of amateurism. Vichy's sport policy followed the moral aim of "rebuilding the nation", was opposed to Léo Lagrange’s sport policy during the Popular Front, and was specifically opposed to professional sport imported from the United Kingdom . They also were used to engrain the youth in various associations and federations, as done by the Hitler Youth or Mussolini's Balilla.

On 7 August 1940, a Commissariat Général à l’Education Générale et Sportive (General Commissioner to General and Sport Education) was created. Three men in particular headed this policy:

- Jean Ybarnegaray, president and founder of the French and International Federations of Basque pelota, deputy and member of François de la Rocque’s Parti Social Français (PSF). Ybarnegaray was first nominated State minister in May 1940, then State secretary from June to September 1940.

- Jean Borotra, former international tennis player (member of “The Four Musketeers”) and also a PSF member, the first General Commissioner to Sports from August 1940 to April 1942.

- Colonel Joseph Pascot, former rugby champion, director of sports under Borotra and then second General Commissioner to Sports from April 1942 to July 1944.

In October 1940, the two General Commissioners prohibited professionalism in two federations (tennis and wrestling), while permitting a three-year delay for four other federations (football, cycling, boxing and Basque pelota). They prohibited competitions for women in cycling or association football. Furthermore, they prohibited, or spoiled by seizing the assets of, at least four uni-sport federations (rugby league, table tennis, Jeu de paume and badminton) and one multi-sport federation (the FSGT). In April 1942, they additionally prohibited the activities of the UFOLEP and USEP multi-sport federations, also seizing their goods which were to be transferred to the “National Council of Sports”.

Quotes

- “Sport well directed is morality in action” (“Le sport bien dirigé, c’est de la morale en action”), Report of E. Loisel to Jean Borotra, 15 October 1940

- “I pledge on my honour to practice sports with selflessness, discipline and loyalty to improve myself and serve better my fatherland” (Sportsman's pledge — « Je promets sur l’honneur de pratiquer le sport avec désintéressement, discipline et loyauté pour devenir meilleur et mieux servir ma patrie »)

- “to be strong to serve better” (IO 1941)

- “Our principle is to seize the individual everywhere. At primary school, we have him. Later on he tends to escape us. We strive to catch up with him at every turn. I have arranged for this discipline of EG (General Education) to be imposed on students (...) We allow for sanctions in case of desertion.” (« Notre principe est de saisir l’individu partout. Au primaire, nous le tenons. Plus haut il tend à s’échapper. Nous nous efforçons de le rattraper à tous les tournants. J’ai obtenu que cette discipline de l’EG soit imposée aux étudiants (…). Nous prévoyons des sanctions en cas de désertion »), Colonel Joseph Pascot, speech on 27 June 1942

See also

- Vichy France

- Popular Front (France)

- History of far right movements in France

- History of France during the twentieth century

- World War II and The Holocaust

References

- ↑ René Rémond, Les droites en France, Aubier, 1982

- ↑ Actes constitutionnels du Gouvernement de Vichy, 1940-1944, France, MJP, université de Perpignan

- ↑ Olivier Wieviorka, “La République recommencée”, in S. Berstein (dir.), La République (in French)

- ↑ Le Moigne, Frédéric (2003). "1944-1951: Les deux corps de Notre-Dame de Paris". Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire (78): 75–88. doi:10.2307/3772572. ISSN 0294-1759. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3772572.

- ↑ Robert Paxton, La France de Vichy, Points-Seuil, 1974

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Christofferson, Thomas R.; Christofferson, Michael S. (2006). France during World War II: From Defeat to Liberation. Fordham University Press. pp. 34, 37–40. ISBN 0-8232-2562-3. https://archive.org/details/franceduringworl00chri.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Jackson, Julian (2001). France: The Dark Years, 1940-1944. Oxford University Press. pp. 139–141. ISBN 0-19-820706-9. https://archive.org/details/france00juli/page/139.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Vinen 2006, p. 76.

- ↑ Alain-Gérard Slama, "Maurras (1858-1952): le mythe d'une droite révolutionnaire " (pp.10-11); article published in L'Histoire in 1992 (in French)

- ↑ See Reggiani, Alexis Carrel, the Unknown: Eugenics and Population Research under Vichy, French Historical Studies, 2002; 25: 331-356

References

- Vinen, Richard (2006). The Unfree French: Life under the Occupation. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-713-99496-4.

External links

- Loi et décret 1940-42

- Sports et Politique

- Politique sportive du gouvernement de Vichy: discours et réalité

- Sport et Français pendant l'occupation

- JP Azéma: Président commission "Politique du sport et éducation physique en France pendant l'occupation."

- Exemples: Badminton, Tennis de table, Jeu de paume Interdits

- Vichy et le football

|