Social:Relationship (archaeology)

An archaeological relationship is the position in space and by implication, in time, of an object or context with respect to another. This is determined, not by linear measurement but by determining the sequence of their deposition – which arrived before the other. The key to this is stratigraphy.

Stratigraphic relationships

Archaeological material would, to a very large extent, have been called rubbish when it was left on the site. It tends to accumulate in events. A gardener swept a pile of soil into a corner, laid a gravel path or planted a bush in a hole. A builder built a wall and back-filled the trench. Years later, someone built a pig sty onto it and drained the pig sty into the nettle patch. Later still, the original wall blew over and so on. Each event, which may have taken a short or long time to accomplish, leaves a context, a deposit of material, on the site. This deposit and its relationship to earlier contexts may show up in section or in plan when viewed from above.

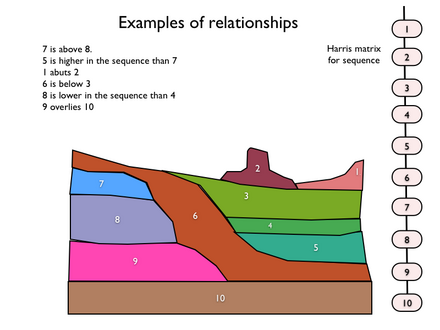

When there are hundreds of these relationships, a formal method of keeping track of them is required. An effective method is to prepare a Harris matrix. Their position in the matrix places the contexts in their sequence in time. Provided the archaeologist has maintained a record of the context in which each artefact was found, the tracing of the contexts by the matrix does equally well for the artefacts (objects).

Types of relationship

Terminology in archaeology is not definitive but the following are typical uses of terms:

- Cuts: A context is said to cut another context if the former's creation removed a part of the latter. For example a ditch cut, cuts all the contexts that made up the ground the ditch was dug into. Reciprocally, a context may be said to be cut by another.

- Overlies: A context is said to overlie another when the overlying context is later in time and makes physical contact with the earlier context.

- Above: A context is said to be above another if created later and, in general, vertically above the other context but not necessarily in physical contact. The description holds even when they are not aligned vertically, if one and the same intervening context lies both below the higher and above the lower.

- Below: A context is said to be below another context if it was created earlier and in general is vertically below the other context but not necessarily in physical contact. The description holds even when they are not aligned vertically, if one and the same intervening context lies both below the higher and above the lower.

- Butts: A context "butts up to" or "abuts" another context when it was created later and contacts the other but in general does not have a vertical physical relationship "above". An example would be a clay floor laid up to the vertical face of an already existing wall.

- Contemporary with. a context may be different but formed in the sequence at the same time. an example of this would be a body in a coffin was already in the coffin when the two where fixed in the sequence. arguments concerning that the skeleton went into the coffin afterwards are based on knowledge of what constituted the formation of the sequence offsite. Is the body created at death or birth? anomalies like this show up the limitations of the stratigraphic sequencing of human made deposits

- Same as. A context upon further investigation may be discovered to the same one another context but assigned different context numbers in error

A relationship that is later in the sequence is sometimes referred to as "higher" in the sequence and a relationship that is earlier "lower" though the term higher or lower does not itself imply a context needs to be physically higher or lower. It is more useful to think of this higher or lower term as it relates to the contexts position in a Harris matrix which is a two dimensional representation of a sites formation in space and time.

See also

- Alignment (archaeology)

- Archaeological association

- Archaeological context

- Archaeological phase

- Archaeological plan

- Archaeological section

- Cut (archaeology)

- Feature (archaeology)

- Fill (archaeology)

- Harris matrix

- Single context recording

References

- The MoLAS archaeological site manual MoLAS, London 1994. ISBN:978-0-904818-40-6. Rb 128pp. bl/wh

- Principles of Archaeological Stratigraphy. 40 figs. 1 pl. 136 pp. London & New York: Academic Press. ISBN:0-12-326651-3

|