Social:Social and economic stratification in Appalachia

Appalachia is a socio-economic region of the Eastern United States. Home to over 25 million people, the region includes mountainous areas of 13 states: Mississippi, Alabama, Pennsylvania, New York, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee , Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Maryland, as well as the entirety of West Virginia.[1]

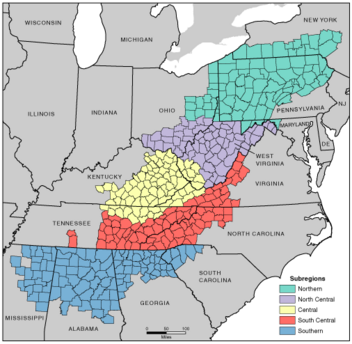

Appalachia is often divided into three subregions: Southern Appalachia (portions of Georgia, Alabama, Mississippi, North and South Carolina, and Tennessee), Central Appalachia (portions of Kentucky, Southern West Virginia, Southern and Southeastern Ohio, Virginia, and Tennessee), and Northern Appalachia (parts of New York, Pennsylvania, Northern West Virginia, Maryland, and Northeastern Ohio).[1] Further divisions can also be made, distinguishing Northern from North Central and Southern from South Central Appalachia.[2] Though all areas of Appalachia face the challenges of rural poverty, some elements (particularly those relating to industry and natural resource extraction) are unique to each subregion. Central Appalachians, for example, experience the most severe poverty, which is partially due to the area's isolation from urban growth centers.[3] The Appalachian region holds 423 counties and covers 206,000 square miles.[4]

The area's rugged terrain and isolation from urban centers has also resulted in a distinct regional culture. Many natives of the region have a distinct pride for their Appalachian heritage regardless of financial status. Outsiders often hold incorrect and overgeneralized beliefs about the area and its inhabitants. These misperceptions, and their relationship to the culture and folklore of this near-isolated area, greatly impact the region's development.[1]

Commerce within the region expanded widely in the 19th century with the advent of modern industries like agriculture, coal-mining, and logging. Many Appalachians sold their rights to land and minerals to large corporations, to the extent that ninety-nine percent of the residents control less than half of the land. Thus, though the area has a wealth of natural resources, its inhabitants are often poor. In addition, decreased levels of education and a lack of public infrastructure (such as highways, developed cities, businesses, and medical services) has perpetuated the region's poor economic standing.[1]

Economic hardship

Power, politics, and poverty

The social and economic stratification of Appalachia comes largely as the result of classism. Many politicians and businessmen took advantage of the region's natural resource industries, such as mountaintop coal mining. Appalachian laborers were heavily exploited, which prevented the region from developing socially or gaining economic independence.

Coal operators and plantation bosses had discouraged education and civic action, allowing workers to become indebted to plantation stores, live in company housing, and generally make themselves vulnerable to exploitation. Additionally, some employers were known to encourage racial divisions in order to divide workers and pit them against each other, spurring competition and serving to lower wages. Workers also experienced heavy discrimination when seeking employment.[5]

Appalachians also suffered under the apathy of local government. Historically, Appalachia has been largely governed by absentee landlords, politicians who control the area without participating in its local economy.[6] For example, officeholders largely ignored the area's lack of infrastructure, despite its major contribution to the region's economic decline. Towns closer to well-developed urban areas that fringe Appalachia (Pittsburgh, Wheeling, Columbus, Cincinnati, Atlanta, Washington, D.C., etc.) are disproportionately better-off than rural regions in the mountainous interior, and lack of accessible transportation has greatly restricted the Appalachian economy. However, the issue has not generally been made a priority by regional political leaders, many of whom eschewed developments that would have been difficult and expensive to establish in the mountainous areas.[3]

Community members who experienced a justifiable fear of punishment for speaking out against the corruption of the status quo developed a habit of compliance rather than democratic institutions for social change. Fearful of punishment, middle class residents allied themselves with the elites rather than challenging the system that colored their everyday lives. Burdened by the choice between exile and exploitation, the actual and potential middle class left the region, widening the gap between the poor and those in power.[5] Observers often perceive a fatalistic attitude on the part of the Appalachian people, as decades of political corruption and disenfranchisement led to weak civic cultures and a sense of powerlessness.[3]

Some academics liken the situation that of third world countries: Residents live on land that cannot be traded outside of trusted circles or used as collateral because, due to the history of unincorporated businesses with unidentified liabilities, there are not adequate records of ownership rights. This "dead" capital is a factor that contributes to the historical poverty of the region, limiting Appalachians' abilities to use their investments in home and other land-related capital.[1] The drastic socioeconomic divide has even led to violent feuds among Appalachians living in remote mountainous regions, as the region fails to be guaranteed political rights.[7][8]

Recently, with the decline of the coal-mining industry, even fewer jobs have become available in the region. With roughly 100,000 jobs left for miners, Appalachians are unable to access jobs or the resources and opportunities necessary to lift themselves out of poverty.[9]

Creation of the Appalachian Regional Committee (ARC)

As of the 1960s, Appalachia had the highest poverty rate and percentage of working poor in the nation. According to research, roughly one third of the region's population was living in poverty.[6]

Having witnessed the region's hardship during a campaign visit, President John F. Kennedy became intent on improving the living standard for Appalachians. In 1963, he proposed the creation of the Appalachian Regional Committee (ARC), which aimed to actively improve the region's economy. The program established by the Appalachian Regional Development Act (ARDA), which was passed by Congress in 1965, under President Lyndon B. Johnson.[6]

The ARC aimed to directly the disenfranchisement of people living in Appalachia. Looking to identify the roots of the region's problems, the ARDA stated: "Congress finds and declares that the Appalachian region of the United States, while abundant in natural resources and rich in potential, lags behind the rest of the Nation in its economic growth and that its people have not shared properly in the Nation's prosperity."[6]

Though the ARC has made improvements, the Appalachian region continues to face socioeconomic hardships. As of 1999, roughly twenty-five percent of Appalachian counties still qualified as "distressed," the commission's lowest socioeconomic ranking.[6]

Economic impact of prisons

The late 20th century saw a large spike in prison development in Appalachia. In the years between 1990 and 1999, there were 245 prisons constructed in the region of Appalachia.[10] Many of these prison were established in rural counties and areas. Though the prisons created jobs, the counties with prisons were found to have lower incomes and more poverty compared to counties without prisons.[11]

Educational disadvantages

In 2000, 80.49 percent of all adults in the United States were high school graduates, as opposed to 76.89 in Appalachia.[12] Almost 30 percent of Appalachian adults are considered functionally illiterate.[12] Education differences between men and women are greater in Appalachia than the rest of the nation, tying into a greater trend of gender inequalities.[12]

Education in Appalachia has historically lagged behind average literacy levels of United States.[13] At first, education in this region was largely nurtured through religious institutions. Children who found time away from family work were often taught to read about the Bible and Christian morality. Then, after the civil war, some districts established primary schools and high schools. People began to access standard education during this period, and higher education in large communities was expanded at that time.[13] Lately, in the late 19th century and early 20th century, education in rural areas has been advanced; some settlement schools and sponsored schools were established by organizations.[14] In the 20th century, the national policy has begun affecting education in Appalachia. Those schools were trying to meet the demands which federal and state settled. Some public schools were facing the problem of gathering funds because of government's No Child Left Behind policy.[13]

Since Appalachia is a place with abundant resources such as coal, mineral, land and forest, the main jobs here are lumbering, mining and farming. None of these jobs need a high education, and employers don't decide the jobs based on their education level. A diploma has not been a priority in job finding. Many children of school age dropped school to help their family work.[15] Women in Appalachia have less opportunity in access of jobs. Many kinds of jobs in this area require a strong body, so that men are preferred than women by employers when they are seeking jobs.[15]

The National Career Development Association has organized a program hoping to increase the education in the Appalachia region, which has been deprived of what other parts of the nation take for granted. The region is primarily utilized for mining, coal, and its other natural resources and farmland. Families that live in these parts have become accustomed to a certain way of life whether it involve school or working. Many kids are not given the opportunity to be successful, only to remain in the family business surrounding one of the many natural resources from their land. The New Opportunity School for Women, NOSW, has begun offering 14 women a 3-week course in Berea, Kentucky, on employment opportunities, skills, basic knowledge that they may not have received. The NOSW also offers a residential housing opportunity to those with low-income after their participation in the course and thereafter. This brings hope to Appalachian women, although it only allows 14 participants, it is a start and that number can only grow with growth within the Appalachian region.[16]

Women from the Appalachian region of Kentucky and surrounding south central Appalachian states share common challenges resulting from low educational attainment, limited employment skills, few strong role models and low self-esteem. The presence of these challenges are directly linked to high incidences[spelling?] of early marriage, teen pregnancies, divorce, domestic violence, substance abuse and high school dropout rates.[16]— National Career Development Association

This program provides interview, job search, computer and other basic skills that are useful in careers for those less skilled. Women can participate freely; no extra money is required.[16] Participants are provided with classes from Monday to Friday, 8 am to 12 pm and afternoon is internship time. These classes are mainly about: job search, interview skill, math, women's health, computer skills, leadership development, and self-protection.[16] (National Career Development Association) Internships not only include working in a real work site, but also include a training of choosing interview clothes and make-ups. The organizer will also hold some events during the weekends except for additional classes. For instance, the American Association of University Women and the Berea Younger Women's Club are available for participants to choose. They can also go for a field trip to some places. All these efforts are conducted to help women build confidence in job finding. As a vulnerable group of people, these rich experiences can help them become an active part in their living communities. After graduating from NOSW, professional agencies will provides each of them counseling services about education. This program has achieved active outcomes. According to a recent survey, after attending this program, 80 percent of those women participants have incomes for less than 10,000 dollars per year with their half high school degree. Among them, 79 percent of graduates are employed, 55 percent of graduates got an associate degree (two-year), a bachelor's degree or even a master's degree, and 35 percent of graduates got a Certification Program degree.[16]

Environmental hardship

The Appalachian region of the Southeastern United States is a leading producer of coal in the country.[17] Research shows that residents who live in close proximity to mountaintop removal (MTR) mines have higher mortality rates than average, and are more likely to live in poverty and be exposed to harmful environmental conditions than people in otherwise comparable parts of the region.[17]

Gender inequalities

Women have traditionally been relegated to the domestic sphere, often lack access to resources and employment opportunities, are disproportionately represented in peripheral labor markets, and have lower wages and higher vulnerability to job loss.[18] Throughout the region, women typically earn 64 percent of men's wages. However, when adjusted for the fact that women take less risky jobs, that require less qualifications, they make roughly the same amount.[19] Women are also often the hardest-hit by poverty—for example, 70 percent of female-headed households with children under the age of six are in distressed counties, a figure substantially higher than the national average.[20]

Still, women play a large role in the social movements and cultural life of Appalachia.

Women have played a major role in the labor and activist movements in the coal-bearing regions of Appalachia. [...] Other crucial roles for women have involved education, literature, healthcare and art, and the promotion of minorities in our region.[21]

There are many achievements conducted by outstanding women leadership. Those women devoted their lifelong efforts in improving their social status and in fighting against poverty in their communities and their living regions. A woman named Kathy Selvage was a citizen lobbyist for years and worked in the fight against a proposal for a Wise County coal-fired plant. She says that Appalachian women are people of action. Lorelei Scarbro helped establish a community center in Whitesville, W.V. to encourage outside activity besides the home and workplace. This reunites them with togetherness and a place to convene about ideas and local build-up. Vivian Stockman is the face of the stand against mountaintop removal and has worked endlessly to spread the word through photos of the detrimental effects it has on the land that people call home. These women, among countless others have done everything they can to end the poverty and depression that has plagued their region for so long.

A coal miner's daughter from Wise County, Va., Selvage has always had a great respect for miners, but when a coal company began blasting off mountaintops in her community, Selvage began working to bring national exposure to mountaintop removal coal mining.[22]

Projects have been created in rural Appalachia to help women save money, especially for retirement. Programs like this aim to help women who have difficulty in raising children and saving money for retirement. Some women have saved little for their retirement and risk running out of money. Appalachian Savings Project was established to alleviate this risk by recreating saving plans for those self-employed women workers who do not have those plans provided by companies. This program aims to help the women workers who have children to care for.

Due to the lagged economic status in Appalachian regions and discrimination, there are an increasing number of women who are getting jobs without comprehensive benefits, such as retirement plans. Instead of consumption, it is an investment to have this saving account. Many mothers put their children first and will not save money for their retirement until their children are independent and do not need help any more. However, this program is encouraging them to save money for their own need instead of their kids'. There are also some complaints about the project. The two most common complaints are that the women do not have enough time to attend the financial classes and that there is not enough money for them to spare.[23]

Outside perspectives and stereotypes

Though mainstream Americans assume that Appalachian culture is homogeneous in the region, many distinct locales and sub-regions exist.[9][24] Overgeneralizations of Appalachianites as impulsive, personalistic, and individualistic "hillbillies" abound. Many scholars speculate that these stereotypes have been created by powerful economic and political forces to justify the exploitation of Appalachian peoples through industrialization and the extraction of natural resources.[9][25] For example, the same forces that put up barriers to prevent the development of civic culture promulgate the image of Appalachian peoples as politically apathetic, without a social consciousness, and deserving of their disenfranchised state. In spite of the region's desperate need for aid, weariness of being represented as "helpless, dumb and poor" often creates an attitude of hostility among Appalachianites.[26]

Origin of the stereotype

These stereotypes have been present for as long as people can remember, as people are unsure of exactly where titles like "hillbillies" came about. It has been said that it came all the way from colonial times when Scotch-Irish immigrants came over to America, and others have said it was given to supporters of King William III during the Williamite war, but was not used much in America until much later. It is known that up until the 1880s, Appalachia was seen just like any other rural area. People then began to view the Appalachian cultures as 'behind' during the industrial revolution, when the way of life was different in Appalachia as they did not adjust as quickly. The classical hillbilly behavior came about in the 1920s during the Great Depression. Appalachian music was a result of prohibition and the hardships that came along with this time period, which was a big part in how people viewed those from Appalachia. After the stereotype was created the media took this and exploited the image of poor people without electricity that were lazy and it became known to be like that.[27]

Appalachians as a separate status group

It has been suggested that Appalachia constitutes a separate status group under the sociologist Max Weber's definition.[28] The criteria are tradition, endogamy, an emphasis on intimate interaction and isolation from outsiders, monopolization of economic opportunities, and ownership of certain commodities rather than others.[28] Appalachia fulfills at least the first four, if not all five.[9] Furthermore, mainstream Americans tend to see Appalachia as a separate subculture of low status. Based on these facts, it is reasonable to say that Appalachia constitutes a separate status group.[1][9]

Depictions of Appalachians in media

Appalachia existed as a relatively unnoticed region until the eighteenth-century when color writers (many of whom wrote for magazines) began to take interest.[29] The original description of Appalachia as a distinct region primarily comes from the insistence of Appalachia's "otherness" by those color writers. The earliest expressions of the Appalachian caricature created by the color writers directly inspired the hillbilly persona known today. The hillbilly stereotype achieved prominence alongside industrial capitalists’ interests in profiting off of the mountain range and its people.[30]

Massey's research finds that the hillbilly is malleable, often used in media as a tool to project the countries’ anxieties upon and stitch together an amalgamation of what society rejects.[25] One wave of anxiety that led to a rise in the media's depiction of the "hillbilly," occurred in the mid-twentieth century following the civil unrest of the 1950s and 60s when many white Americans felt their autonomy was under threat.[25] Television shows such as The Beverly Hillbillies (which did not depict an Appalachian family but did perpetuate poor-white stereotypes), which ran from 1962 to 1971, emerged along with The Andy Griffith Show and Hee Haw. All of these series featured ridicule and humor based around negative characteristics of rural, mountain peoples.[31]

Another wave of anxiety occurred in the late-twentieth-century into the twenty-first.[25] Today, reality television has assumed the role previously filled by sitcoms like The Beverly Hillbillies. Series such as Call of the Wildman and Moonshiners fulfill the demand to observe the "other," and, perhaps unconsciously, perpetuate the stereotype of the toothless, barefoot, moonshiner hillbilly.[31]

Television

Appalachian stereotyping was shown in early television when The Beverly Hillbillies was released. The people in this show were portrayed to be the classic Appalachian resident, which painted the culture in a bad way from the beginning. The representation continued on after this and continued to portray those in Appalachia as hillbillies. From then on it was comedic to see an Appalachian family or Appalachian culture; as the representation that was shown was merely to make fun of the culture. This stereotype expands on more than just the physical characteristics of these people, but also their views. It is assumed that they are conservative, uneducated, and even racist. Carter Country is a show that demonstrated race and the uneducated views of some in Appalachia. It gives a view on a newly integrated area and how people in the Appalachian area adjust to it.[32]

Movies

Appalachia has been portrayed in many movies throughout the years, some of the most notable films include October Sky, We Are Marshall, Dark Waters, The Devil All The Time, Logan Lucky, Hillbilly Elegy, Silent Hill, and Wrong Turn. Movies also highlight Appalachia in a negative way. This began as early as 1904 in a silent film titled The Moonshiner. In this movie, all that was featured was people making moonshine and trying to get away with it, which is a constant theme. Other genres also bring in an Appalachian theme like Deliverance. This movie is a thriller about people that camp in an Appalachian area, and it paints locals in a negative way. Though there are movies that get the culture wrong, some show Appalachia correctly.

See also

- American ethnicity

- Appalachian Institute

- Appalachian music

- Hobet Coal Mine

- Mountain white

- Overmountain Men

- Poor White

- Rising Appalachia

- Social stratification

- Tuckahoe and Cohee

- Max Weber

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Hurst, Charles. (1992). Inequality in Appalachia. Social Inequality: Forms, Causes, and Consequences, 6th Edition. Pearson Education. pp 62-68.

- ↑ "Subregions in Appalachia" (in en-US). https://f1-stage-apprc.pantheonsite.io/map/subregions-in-appalachia/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Tickamyer, Ann; Cynthia, Duncan. (1990). Poverty and Opportunity Structure in Rural America. Annual Review of Sociology. 16:67-86. Retrieved November 28 from Academic Search Premier.

- ↑ "About the Appalachain Region". https://www.arc.gov/about-the-appalachian-region/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Duncan, Cynthia Mildred. (1999). Civic Life in Gray Mountain. Connection: New England's Journal of Higher Education & Economic Development, Vol. 14, Issue 2, Retrieved November 29 From Academic Search Premier.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "ARC History". Appalachian Regional Commission. http://www.arc.gov/about/archistory.asp. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ↑ Otterbein, F. K (2000). "Five Feuds: An Analysis of Homicides in Eastern Kentucky in the Late Nineteenth Century". American Anthropologist 102 (2): 231–243. doi:10.1525/aa.2000.102.2.231.

- ↑ Billings, D. B; Blee, K.M (1996). "Where the Sun Set Crimson and the Moon Rose Red": Writing Appalachia and the Kentucky Mountain Feuds". Southern Cultures 2 (3/4): 329–352. doi:10.1353/scu.1996.0005.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Billings, Dwight. (1974). Culture and Poverty in Appalachia: a Theoretical Discussion and Empirical Analysis. Social Forces vol. 53:2. Retrieved November 29, 2007, from Academic Search Premier.

- ↑ Mauer, Marc. "Invisible punishment: the collateral consequences of mass imprisonment". New Press. https://adams.marmot.org/Record/.b21224870.

- ↑ Todd Perdue, Robert; Sanchagrin, Kenneth (2016). "Imprisoning Appalachia: The Socio-Economic Impacts of Prison Development". Journal of Appalachian Studies (University of Illinois) 22 (2): 210–223. doi:10.5406/jappastud.22.2.0210. https://scholarlypublishingcollective.org/uip/jas/article/22/2/210/226961/Imprisoning-Appalachia-The-Socio-Economic-Impacts. Retrieved 27 March 2022.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Shaw, Thomas; DeYoun, Allan; Redemacher, Eric. (2005). Educational Attainment in Appalachia: Growing with the Nation, but Challenges Remain. Journal of Appalachian Studies. Volume 10 Number 3. Retrieved November 29, 2007, from Academic Search Premier.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 DeYang, A (2006). Introduction to Education section, Encyclopedia of Appalachia. Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 1517–1521.

- ↑ Alvic, P (2006). "Settlement, Mission, and Sponsored Schools". Encyclopedia of Appalachia: 1551.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "New Opportunity School for Women: A unique career and education program in Appalachia". National Career Development Association. http://www.ncda.org/aws/NCDA/pt/sd/news_article/69382/_PARENT/layout_details_cc/false. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Francis, Caroline. "New opportunity school for women: A unique career and education program in Appalachia". National Career Development Association. http://www.ncda.org/aws/ncda/pt/sd/news_article/69382/_parent/layout_details_cc/false. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Hendryx, Michael (Spring 2011). "Poverty and Mortality Disparities in Central Appalachia: Mountaintop Mining and Environmental Justice". Journal of Health Disparities Research and Practice 4 (4): 44–53. http://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=jhdrp.

- ↑ Denham, Sharon; Mande, Man; Meyer, Michael; Toborg, Mary. (2004). Providing Health Education to Appalachia Populations. Holistic Nursing Practices 2{X)4:I8(6):293-3O1. Retrieved November 30 from Academic Search Premier.

- ↑ Oberhauser, Ann; Latimer, Melissa. (2005). Exploring Gender and Economic Development in Appalachia. Journal of Appalachian Studies. Volume 10 Number 3. Retrieved November 28 from Academic Search Premier.

- ↑ Thorne, Deborah; Tickamyer, Ann; Thorne, Mark. (2005). Poverty and Income in Appalachia. Journal of Appalachian Studies. Volume 10 Number 3. Retrieved November 29 from Academic Search Premier.

- ↑ "The Women of Appalachia". Appalachian Voices. http://appvoices.org/appalachianwomen/. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ↑ "The Heart of The Mountaintop Removal Movement". Appalachian Voices. 2011-02-04. http://appvoices.org/2011/02/04/mountaintop-removal/. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ↑ Ludden, Jennifer. "Rural Appalachia Helps Some Women Save For Retirement". npr. https://www.npr.org/2014/03/20/291912681/rural-appalachia-helps-some-women-save-for-retirement. Retrieved 5 August 2014.

- ↑ Oberhauser, Ann M. (1995). Towards a gendered regional geography: Women and work in rural Appalachia. Growth & Change, 00174815, Spring 95, Vol. 26, Issue 2. Retrieved November 29 from Academic Search Premier Database.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Massey, C. (2007). Appalachian Stereotypes: Cultural History, Gender, and Sexual Rhetoric. Journal of Appalachian Studies, 13(1/2), 124-136. Retrieved February 17, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/41446780.

- ↑ Mellon, Steve. (2001). Carefully Choosing the Images of Poverty. Nieman Reports, 00289817, Vol. 55, Issue 1. Retrieved November 28 from Academic Search Premier.

- ↑ Hanson, Todd A. (31 January 2019). "Hillbilly: The history behind an American cultural icon (Daily Mail WV)" (in en). https://www.wvgazettemail.com/dailymailwv/daily_mail_features/hillbilly-the-history-behind-an-american-cultural-icon-daily-mail-wv/article_8b2df15d-b162-5083-87e4-ed3a55e787d6.html.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Hurst, Charles. (1992). The Theory of Social Status. Social Inequality: Forms, Causes, and Consequences, 6th Edition. Pearson Education. pp 46.

- ↑ Holtkamp, C.; Weaver, R. C. (2018). Placing Social Capital: Place Identity and Economic Conditions in Appalachia. Southeastern Geographer, 58(1), 58–79. https://doi-org.10.1353/sgo.2018.0005.

- ↑ Richards, M. S. (2019). "Normal for His Culture": Appalachia and the Rhetorical Moralization of Class. Southern Communication Journal, 84(3), 152–169. https://doi-org.10.1080/1041794X.2019.1566399.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Cooke-Jackson, Angela; Hansen, Elizabeth. (2008). Appalachian Culture and Reality TV: The Ethical Dilemma of Stereotyping Others. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 23:3, 183-200, DOI: 10.1080/08900520802221946.

- ↑ Newcomb, Horace (1979). "Appalachia on Television: Region as Symbol in American Popular Culture". Appalachian Journal 7 (1/2): 155–164. ISSN 0090-3779. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40932731.

|