Social:The Beauty Myth

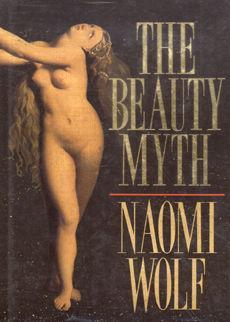

Cover of the first edition | |

| Author | Naomi Wolf |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Publisher | Chatto & Windus |

Publication date | 1990 |

| Media type | |

| ISBN | ISBN:978-0-385-42397-7 |

| Followed by | Fire with Fire: The New Female Power and How To Use It |

The Beauty Myth: How Images of Beauty Are Used Against Women is a nonfiction book by Naomi Wolf, originally published in 1990 by Chatto & Windus in the UK and William Morrow & Co (1991) in the United States. It was republished in 2002 by HarperPerennial with a new introduction.

The basic premise of The Beauty Myth is that as the social power and prominence of women have increased, the pressure they feel to adhere to unrealistic social standards of physical beauty has also grown stronger because of commercial influences on the mass media. This pressure leads to unhealthy behaviors by women and a preoccupation with appearance in both sexes, and it compromises the ability of women to be effective in and accepted by society.

Summary

In her introduction, Wolf offers the following analysis:

| “ | The more legal and material hindrances women have broken through, the more strictly and heavily and cruelly images of female beauty have come to weigh upon us... [D]uring the past decade, women breached the power structure; meanwhile, eating disorders rose exponentially and cosmetic surgery became the fastest-growing specialty... [P]ornography became the main media category, ahead of legitimate films and records combined, and thirty-three thousand American women told researchers that they would rather lose ten to fifteen pounds than achieve any other goal...More women have more money and power and scope and legal recognition than we have ever had before; but in terms of how we feel about ourselves physically, we may actually be worse off than our unliberated grandmothers.[1] | ” |

Wolf also posits the idea of an iron maiden, an intrinsically unattainable standard that is then used to punish women physically and psychologically for their failure to achieve and conform to it. Wolf criticizes the fashion and beauty industries as exploitative of women, but claims the beauty myth extends into all areas of human functioning. Wolf writes that women should have "the choice to do whatever we want with our faces and bodies without being punished by an ideology that is using attitudes, economic pressure, and even legal judgments regarding women's appearance to undermine us psychologically and politically". Wolf argued that women were under assault by the "beauty myth" in five areas: work, religion, sex, violence, and hunger. Ultimately, Wolf argues for a relaxation of normative standards of beauty.[2]

Impact

Wolf's book was a quick bestseller, garnering intensely polarized responses from the public and mainstream media, but winning praise from many feminists. Second-wave feminist Germaine Greer wrote that The Beauty Myth was "the most important feminist publication since The Female Eunuch", and Gloria Steinem wrote: "The Beauty Myth is a smart, angry, insightful book, and a clarion call to freedom. Every woman should read it."[3] British novelist Fay Weldon called the book "essential reading for the New Woman",[4] and Betty Friedan wrote in Allure magazine that "The Beauty Myth and the controversy it is eliciting could be a hopeful sign of a new surge of feminist consciousness."

With the publication of The Beauty Myth, Wolf became a leading spokesperson of what was later described as the third wave of the feminist movement.

Criticism

In Who Stole Feminism? (1994) Christina Hoff Sommers criticized Wolf for publishing the claim that 150,000 women were dying every year from anorexia in the United States, writing that the actual figure was more likely to be somewhere between 100 and 400 per year.[5]

Similarly, a 2004 paper compared Wolf's eating disorder statistics to statistics from peer-reviewed epidemiological studies and concluded that 'on average, an anorexia statistic in any edition of The Beauty Myth should be divided by eight to get near the real statistic.' Schoemaker calculated that there are about 525 annual deaths from anorexia, 286 times less than Wolf's statistic.[6]

Humanities scholar Camille Paglia also criticized the book, arguing that Wolf's historical research and analysis was flawed.[7]

Connection to women's studies

Within women's studies, scholars [who?] posit that the Beauty Myth is a powerful force that keeps women focused on and distracted by body image and that provides both men and women with a way to judge and limit women due to their physical appearance. Magazines, posters, television ads and social media sites are, in this hypothesis, among the many platforms today that perpetuate beauty standards for both men and women. The daily presence and circulation of these platforms, it is argued, makes escaping these ideals almost impossible. Women and men alike are faced with ideal bodies, bodies that are marketed as attainable through diets and gym memberships. However, for most people these beauty standards are neither healthy nor achievable through diet or exercise. Women often place a greater importance on weight loss than on maintaining a healthy average weight, and they commonly make great financial and physical sacrifices to reach these goals. Yet failing to embody these ideals makes women targets of criticism and societal scrutiny.

Perfectionistic, unattainable goals are cited as an explanation for the increasing rates of plastic surgery and anorexia nervosa. Anorexia is one of the most prevalent eating disorders in Western countries "affecting an estimated 2.5 million people in the United States alone."[8] Of this number, more than 90 percent of anorexics are girls and young women. They suffer from a "serious mental health disease that involves compulsive dieting and drastic weight loss". This weight loss is the result of deliberate self-starvation to achieve a thinner appearance, and it is frequently associated with the disorder bulimia. Anorexia's deep psychological roots make it difficult to treat and often extend the recovery process into a life-long journey.

Some feminists believe the beauty myth is part of a system that reinforces male dominance. According to Naomi Wolf, as women increasingly focus their attention on their physical appearance, their focus on equal rights and treatment takes a lower priority. The same is argued in Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex, in which she recounts the effects of societies that condition adolescent girls and young women to behave in feminine ways. According to Beauvoir, these changes encompass a "huge array of social expectations including physical appearance, but unlike the social expectations on boys, the social expectations on girls and women usually inhibit them from acting freely".[9] In her argument, Beauvoir cites things such as clothing, make-up, diction and manners as subjects of scrutiny that women face but men do not.

According to Dr. Vivian Diller's book Face It: What Women Really Feel as their Looks Change and What to Do About It, "most women agree, reporting the good looks continue to be associated with respect, legitimacy, and power in their relationships".[10][page needed] Diller writes that in the commercial world, hiring, evaluations and promotions based on physical appearance push women to place the importance of beauty above that of their work and skills.

Over the course of history, beauty ideals for women have changed drastically to represent societal views.[11] Women with fair skin were idealized and segregated and used to justify the unfair treatment of dark-skinned women.[citation needed] In the early 1900s, the ideal female body was represented by a pale complexion and cinched-waist; freckles, sun spots, and/or skin imperfections led to scrutiny by others. In 1920, women with a thinner frame and small bust were seen as beautiful, while the ideal body type of full-chested, hourglass figures began in the early 1950s, leading to a spike in plastic surgery and eating disorders. Society is continually shifting the socially constructed ideals of beauty imposed on women.[citation needed]

Film

In February 2010, a filmed 42-minute lecture delivered by Naomi Wolf at California Lutheran University, entitled The Beauty Myth: The Culture of Beauty, Psychology, & the Self, was released on DVD by Into the Classroom Media.[12]

References

- ↑ The Beauty Myth. pp. 10

- ↑ The Beauty Myth, pp. 17–18, 20, 86, 131, 179, 218.

- ↑ "The Beauty Myth". Powells.com. http://www.powells.com/biblio/2-9780385423977-7.

- ↑ Hubbard, Kim (June 24, 1991), The Tyranny of Beauty, To Naomi Wolf, Pressure to Look Good Equals Oppression, People.

- ↑ Sommers, Christina Hoff (1995). Who Stole Feminism? How Women Have Betrayed Women. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 11, 12. ISBN 0-684-80156-6. https://archive.org/details/whostolefeminism00chri/page/11.

- ↑ Schoemaker, Casper (2004). "A critical appraisal of the anorexia statistics in The Beauty Myth: introducing Wolf's Overdo and Lie Factor (WOLF).". Eat Disord 12 (2): 97–102. doi:10.1080/10640260490444619. PMID 16864310.

- ↑ "If you want to see what’s wrong with Ivy League education, look at The Beauty Myth. Paglia, Camille (1992). Sex, Art, Culture: New Essays. New York: Vintage, ISBN:978-0-679-74101-5.

- ↑ Parks, Peggy J. (2009). Anorexia. San Diego, CA: ReferencePoint Press. pp. 6–10. ISBN 9781601520425. https://archive.org/details/anorexia0000park_n5h4.

- ↑ Scholz, Sally J. (2010). Feminism: A Beginner's Guide. Oxford: Oneworld. pp. 158–164. ISBN 9781851687121.

- ↑ Diller, Vivian; Jill Muir-Sukenick (2011). Michele Willens. ed. Face It: What Women Really Feel as their Looks Change and What to Do About It: A Psychological Guide to Enjoying Your Appearance at Any Age (3rd ed.). Carlsbad, Calif.: Hay House. ISBN 9781401925413.

- ↑ Ryle, Robyn (2012). Questioning Gender: A Sociological Exploration. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE/Pine Forge Press. ISBN 9781412965941.

- ↑ Wolf, Naomi (2010). The Beauty Myth: The Culture of Beauty, Psychology, & the Self. Los Angeles: Into the Classroom Media.

External links

- Rebecca Onion, "A Modern Feminist Classic Changed My Life. Was It Actually Garbage?" March 30, 2021, re-assessment of the book at Slate.

|