Social:Yugambeh–Bundjalung languages

| Yugambeh–Bandjalangic | |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity | Bundjalung people (Minyungbal, Widjabal), Western Bundjalung people, Githabul, Yugambeh people |

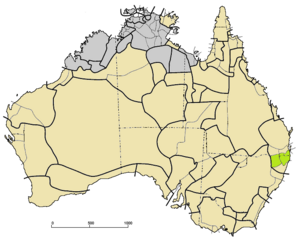

| Geographic distribution | Queensland and New South Wales, Australia |

| Linguistic classification | Pama–Nyungan

|

| Subdivisions |

|

| ISO 639-3 | bdy |

| Glottolog | band1339[1] |

Bandjalangic languages (green) among other Pama–Nyungan (tan) | |

Bundjalung is classified as Severely Endangered by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

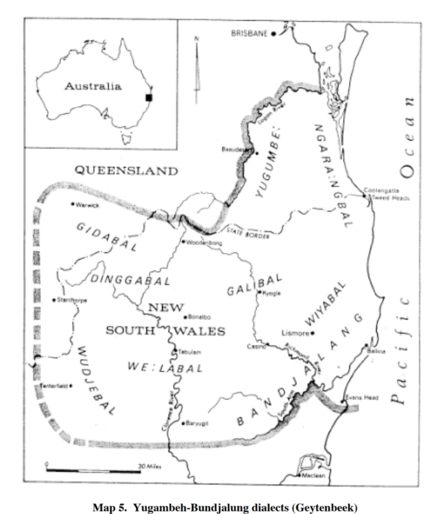

Yugambeh–Bundjalung, also known as Bandjalangic, is a branch of the Pama–Nyungan language family, that is spoken in north-eastern New South Wales and South-East Queensland.

Yugambeh–Bundjalung was historically a dialect continuum consisting of a number of varieties, including Yugambeh, Nganduwal, Minjangbal, Njangbal (Nyangbal), Biriin, Baryulgil, Waalubal, Dinggabal, Wiyabal, Gidabal, Galibal, and Wudjeebal. Language varieties in the group vary in degree of mutual intelligibility, with varieties at different ends of the continuum being mostly unintelligible.[2] These dialects formed four clusters:

- Tweed-Albert Language (Yugambeh)

- Condamine-Upper Clarence (Githabul)

- Lower Richmond (Eastern Bundjalung – Nyangbal, Minyangbal and Bandjalang proper)

- Middle Clarence (Western Bundjalung)

Bowern (2011) lists Yugambeh, Githabul, Minyangbal, and Bandjalang as separate Bandjalangic languages.[3] All Yugambeh–Bundjalung languages are nearly extinct. Bandjalang proper has the greatest number of speakers: 113, while the other dialects have a total of 26 speakers.[4]

Gowar (Guwar) and Pimpama may be related to the Bandjalangic languages rather than to Durubalic.

Nomenclature

The Yugambeh–Bundjalung language chain is spoken by numerous social/cultural groups some of whom have historically preferred to identify with their particular dialect name, e.g. Githabul, Yugambeh, especially as some groups do not see particular varieties as being 'the same language'.

W. E. Smythe, a doctor in Casino, knew the Bundjalung quite well noting in his time the language was spoken widely. He compiled a grammar of the Casino dialect in the 1940s, mistakenly believing he was writing a grammar for the whole language group. When speaking of the name of language he noted:

'For the linguistic group as a whole I have used the term 'Bandjalang', with which some may disagree. Among the people themselves there is a good deal of confusion. Some say the tribal name should be 'Beigal[Baygal]' (man, people), others that there never was any collective name, while others again state that 'Bandjalang', besides being the specific name of one of the local groups, was also in use as a covering term for alI. For convenience I am doing the same.'[2]

Adding to the confusion is the use of multiple names by different groups, i.e. what one group calls another may not be what it calls itself, or the name of a dialect may change, e.g. Terry Crowley was originally told Wehlubal for the Baryulgil dialect, while a later researcher was given Wirribi.

The earliest sources of anthropological work dated from the mid to late 1800s does not give a name for the entire language chain; however, it is clear from sources that particular writers were aware of it, in most instances referring to it by their local variety name or with a descriptor like 'this language with slight variation'. It was not until the early 1900s, with the advent of Aboriginal Protection Boards, that non-Indigenous sources begin overtly naming wider language groups; this, however, was at a detriment to local dialect and clan names that were subsumed under the board's chosen name. Yugambeh–Bundjalung's position at the Queensland–NSW border led to two standard terms: Yugambeh/Yugumbir on the Queensland side and Bundjalung/Bandjalang on the NSW side. It was for this reason that Margaret Sharpe named the chain Yugambeh–Bundjalung, the terms being the most northerly and southerly respectively as well.[5]

Modern Yugambeh–Bundjalung-speaking peoples are often aware of and use the overarching terms Yugambeh and Bundjalung, some groups in conjunction with their own name e.g. Byron Bay Bundjalung – Arakwal.[6] As these words also refer to individual dialects some groups object to their usage, Crowley and Sharpe both agree that Yugambeh referred to the Beaudesert dialect, also known by the clan name Mununjali, and Bundjalung originally referred to the Bungawalbin Creek/Coraki dialect, though the Tabulam people claim they are the original Bundjalung, and use Bandjalang in opposition.[5][7]

Geographic distribution

Yugambeh-Bandjalang is spoken over a wide geographic area; the Pacific Ocean to the east and the Logan River catchment as the northern boundary, the Clarence River forming the south and south-western boundaries, and the Northern Tablelands marking the western boundary.[2]

Many of the dialects and branches are confined by natural features such as river basins, mountain ranges and dense bushland.

Dialects

Yugambeh-Bundjalung or just Bundjalung is used as a cover term for the dialect chain as well as to refer to certain individual dialects. At the time of the first European settlement in the mid-1800s, the Yugambeh-Bundjalung peoples on the north coast of New South Wales and southeast of Queensland spoke up to twenty related dialects. Today only about nine remain. All were mutually intelligible with neighbouring dialects. The dialects form recognisable clusters that share phonological and morphological features, as well as having higher degrees of mutual intelligibility.[2]

Clusters

| Language Cluster | Area spoken | Dialects |

|---|---|---|

| Condamine-Upper Clarence | Between the Upper Condamine and Upper Clarence River catchments | Galibal, Warwick Dialect, Gidabal, Dinggabal |

| Lower Richmond | Between the Lower Richmond and Lower Clarence River Catchments | Nyangbal, Bandjalang, Wiyabal, Minyangbal |

| Middle Clarence | Middle Clarence catchment | Wahlubal, Casino Dialect, Birihn, Baryugil |

| Tweed-Albert | Between the Logan and Tweed River catchments. | Yugambeh, Ngarangwal, Nganduwal |

Dialects

Condamine – Upper Clarence

| # | Co-ordinates | Dialect | Areas spoken | Alternate names |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Kalibal | Kyogle area | Dinggabal, Galibal, Gullybul | |

| 2. | Dinggabal | Tabulam area | Dingabal, Dingga, Gidabal | |

| 3. | Gidabal | Woodenbong and Tenterfield area | Githabul | |

| 4. | Geynan | Warwick area | Warwick dialect |

Middle Clarence

| # | Co-ordinates | Dialect | Area spoken | Alternate names |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Wahlubal | South of Tabulam to Drake | Bandjalang, Western Bandjalang | |

| 2. | Wudjehbal/ Djanangmum | Casino area | Bandjalang | |

| 3. | Birihn | Rappville area | Bandjalang | |

| 4. | Baryulgil | Baryulgil area | Bandjalang |

Lower Richmond

| # | Co-ordinates | Dialect | Area spoken | Alternate names |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Nyangbal | Ballina area | Bandjalang | |

| 2. | Bandjalang Proper | Bungwalbin Creek & Casino area | Bandjalang | |

| 3. | Wiyabal | Lismore area | Wudjehbal, Bandjalang | |

| 4. | Minyangbal | Byron Bay area | Bandjalang, Arakwal |

Tweed–Albert

| # | Co-ordinates | Dialect | Area spoken | Alternate names |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Yugambeh | Logan & Albert River basins | Yugam, Yugambah, Minyangbal | |

| 2. | Ngarangwal | Coomera & Nerang River basins | Nerang, Nerangbal, Yugambeh, Yugam, Minyangbal | |

| 3. | Nganduwal | Tweed River basins | Yugambeh, Yugam, Ngandu, Minyangbal |

Dialectal differences

Until the 1970s all language and linguist work to date had been undertaken on individual varieties, with major grammar work undertaken on Githabul, Minyangbal, Yugambeh, and the Casino dialect.[8][9][10] Terry Crowley was the first to publish a study of the wider Bandjalangic language group, titled 'The middle Clarence dialects of Bandjalang', it included previously unpublished research on the Casino dialect as an appendix. Crowley analysed not only the vocabulary but grammar of the varieties including comparative cognate figures and examples from various dialects.[11]

Phonology

Vowel

Varieties of Yugambeh-Bundjalung may have a vowel system of either three or four vowels that also contrast in length, resulting in either six or eight phonemic vowels in total.[12]

In practical orthography and some descriptions of the language, the letter "h" is often used after the vowel to indicate a long vowel.[12]

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| High | i iː | u uː |

| Mid | (e eː) | |

| Low | a aː | |

Vowel alternations

/a/ and /e/ are neutralised as [ɛ] before /j/.

The low central vowel /a/ can be fronted and raised following a palatal consonant, and backed following a velar consonant.[12]

Unstressed short vowels can be reduced to the neutral central vowel schwa in a similar way to English.[12]

Consonants

Yugambeh-Bundjalung has a smaller inventory of consonant phonemes than is typical of most Australian languages, having only four contrastive places of articulation and only one lateral and one rhotic phoneme.

| Peripheral | Laminal | Apical | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Velar | Palatal | Alveolar | |

| Nasal | m ⟨m⟩ | ŋ ⟨g⟩ | ɲ ⟨ň⟩ | n ⟨n⟩ |

| Obstruent | b ⟨p⟩ | ɡ ⟨k⟩ | ɟ ⟨ť⟩ | d ⟨t⟩ |

| Lateral | l ⟨l⟩ | |||

| Rhotic | ɾ ⟨r⟩ | |||

| Semivowel | w ⟨w⟩ | j ⟨j⟩ | ||

Obstruents

Although the standard IPA symbols used in transcription of the language are the voiced stop symbols, these segments are better characterised as obstruents because they are realised more often as fricatives or affricates than actual stops. There is no contrast in Yugambeh-Bundjalung between these manners of articulation.[12]

Yugambeh-Bundjalung varieties do not have voicing contrasts for their obstruent sequences, and so phonological literature varies in its representation of these consonants- some linguists have chosen the symbols /p/, /k/, /c/, /t/, and others have decided upon /b/, /g/, /ɟ/, /d/. Generally, these consonants are phonetically voiceless, except when following a homorganic nasal segment.[12]

Nasals

When nasal stops occur syllable-finally, they are often produced with a stop onset as a free variant.[12]

Lateral

The lateral phoneme can appear as a flap rather than an approximant, and sometimes occurs prestopped as a free variant in the same way as nasals.[12]

Rhotic

The rhotic phoneme has several surface realisations in Yugambeh-Bundjalung. Between vowels, it tends to be a flap, although it can sometimes be an approximant, and it is usually a trill at the end of syllables.[12]

Semi-vowels

The existence of semi-vowels in Yugambeh-Bundjalung can be disputed, as in many Australian languages. Some linguists posit their existence in order to avoid an analysis that involves onset-less syllables, which are usually held to be non-existent in Australian languages. Some phonologists have found that semi-vowels can be replaced with glottal stops in some varieties of Yugambeh-Bundjalung.[12]

Stress

Yugambeh-Bundjalung is a stress-timed language and is quantity-sensitive, with stress being assigned to syllables with long vowels. Short unstressed vowels tend to be reduced to the neutral vowel schwa.[12]

Syllable structure

Like many Australian languages, Yugambeh-Bundjalung is thought to have a constraint that states that all syllables must have a consonant onset. Only vowels are permitted as the syllable nucleus, and these may be long or short. Syllable codas are also permitted, with long or short vowels in the nucleus. However, long vowels are not permitted to occur in adjacent syllables.[12]

Phonotactics

Consonant clusters

Yugambeh-Bundjalung does not permit clusters of the same consonant, or clusters that begin with an obstruent phoneme or end with an approximant, except the labio-velar glide. All homorganic nasal-obstruent clusters occur in the language. Clusters usually only involve two segments, but clusters of three may occur if an intervening vowel is deleted by some process.[12]

Vocabulary

Cognate comparison between the most southern and northern dialects, Bandjalang (Proper) and Yugambeh (Proper), shows 52% similarity. Cognate similarity is highest between dialects within branches, typically being ~80%, these percentages are even higher amongst the Tweed-Albert dialects at ~90%. Between branches of the family this rate falls to ~60–70% between neighbouring clusters.[7]

Isogloss

Some vocabulary differences in common vocabulary are present:

'What/something' – nyang in southern varieties contrasts with minyang in northern varieties. (Both were used in the centrally located Lismore dialect).

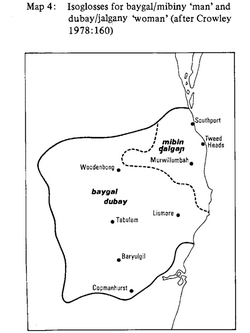

The northern Tweed-Albert language have mibin for 'man' and jalgany for 'woman', compared to the use of baygal and dubay by other varieties respectively. The difference in words for men is significant as groups often use it for identification as well as a language name (Mibinah = language lit. 'of man', Baygalnah = language lit. 'of man').

Another vocabulary isogloss is jabu ('boy') and mih ('eye') used in all branches, except the Middle-Clarence language which uses janagan and jiyaw respectively.[7][13]

Vowel shifts

A north to south shift of /a/ to /e/ (with an intermittent /i/ present in some varieties) in some common vocabulary.

- 'Who': ngahn/ngihn/ngehn

- 'You': wahlu/wihlu/wehlu

A north to south shift of /i/ to /a/ (with an intermittent/e/ present in some varieties) occurring on the demonstrative set.

- 'This': gali/gale/gala

- 'That': mali/male/mala

A shift of /a/ to /u/ in the Tweed-Albert dialects.

- 'No': yugam/yagam

- 'Vegetable': nungany/nangany[14]

Grammar

Crowley's research found a number of grammar differences between the varieties and clusters. Further research by Dr. Margaret Sharpe detailed these finer differences.

Noun declensions

All varieties within the family use suffixes to decline nouns. Most are universal; however, there are a few poignant differences. A complex system exists whereby suffixes are categorised into orders, with the order and use governed by universal rules.

Locative

A past and non-past form of the locative exists in Githabul, Yugambeh and Minyangbal.

Abessive

The abessive -djam is present in Yugambeh and Githabul, being used on nouns and verbs (use on verbs does not occur further south).

Gender

A system of marking four grammatical genders (two animate – human and animal, and two inanimate – arboreal and neuter) with the use of suffixes is present in three of the clusters. The morphological forms and usage of these gender suffixes vary between the clusters, with some dialects marking both demonstratives and adjectives, others marking solely adjectives.

Verbal morphology

The extensive use of suffixes extends to verbs as well; the suffix system is the same throughout the language group with a few minor differences.

The imminent aspect (used in other varieties for most instances that use the English future tense) has shifted in the Tweed-Albert Language to an irrealis mode, now denoting the potential mood, while the continuous aspect in conjunction with a time word is now used for future tense situations.

Example of differences in -hny suffix usage:

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

The purposive suffix is -yah in the Tweed-Albert and Condamine-Upper Clarence languages, while it is -gu in the other two branches.

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

Script error: No such module "Interlinear".

Vocabulary

| # | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name/word | Pronounced | Synonyms | Dialect | Meaning |

| 1 | ||||

| Ballina | English | Accidental or deliberate corruption of the Aboriginal words bullinah and boolinah and/or balloona, balloonah, balluna, bullenah, bullina and bulluna. | ||

| 2 | ||||

| Bullenah | Balluna, bullina, bulluna, balloona, balloonah | 'Blood running from the wounded' or 'the place of dying' or 'the place of the wounded after a fight' or 'place where a battle was fought and people were found dying'. | ||

| 3 | ||||

| Bullen-bullen | "Bul-na" | 'A fight'. | ||

| 4 | ||||

| Bulun | 'River'. | |||

| 5 | ||||

| Bullinah | Boolinah | 'Place of many oysters'. | ||

| 6 | ||||

| Cooriki | Gurigay, hooraki, kurrachee | 'The meeting of the waters'. | ||

| 7 | ||||

| Coraki | English | Accidental or deliberate corruption of the Aboriginal words kurrachee, gurigay, hooraki and cooriki | ||

| 8 | ||||

| Dahbalam | Tabulam | Galibal | ||

| 9 | ||||

| Gunya | 'A traditional native home, made from wood and bark'. | |||

| 10 | ||||

| Gum | Ngarakwal | Crossing | ||

| 11 | ||||

| Gummin | 'Father's mother'. | |||

| 12 | ||||

| Gummingarr | 'Winter camping grounds'. | |||

| 13 | ||||

| Jurbihls | Djuribil | Githabul | 'Refers to both a site and the spirit that resides there'. | |

| 14 | ||||

| Maniworkan | 'The place where the town of Woodburn is located'. | |||

| 15 | ||||

| Nguthungali-garda | Githabul | 'Spirits of our grandfathers'. | ||

| 16 | ||||

| Uki | "Yoo-k-eye" | 'A water fern with edible roots'. | ||

| 17 | ||||

| Wollumbin | Ngarakwal | 'Patriarch of mountains', 'Fighting Chief', 'Place of Death and Dying', 'Site at which one of the chief warriors lies' or 'Cloud Catcher'. | ||

| 18 | ||||

| Woodenbong | 'Wood ducks on water'. | |||

| 19 | ||||

| Wulambiny Momoli | Mount Warning | Ngarakwal | 'Turkey Nest'. |

| # | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name/word | Pronounced | Synonyms | Dialect | Meaning |

| 1 | ||||

| Dirawong | Dira-wong | Dirawonga, Goanna | Creator Being spirit that looked like a Goanna but behaved just like humans. |

| # | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name/word | Pronounced | Synonyms | Dialect | Meaning |

| 1 | ||||

| Weeum | Wee-um | 'Clever Man' also known as 'Man of high degree of initiation'. | ||

| 2 | ||||

| Wuyun Gali | Wu-yun Ga-li | 'Clever Man' also known as 'Doctor' | ||

| 3 | ||||

| Cooradgi | Gidhabal and Dinggabal | 'Clever Men of the tribe' who could cast spells of sleep or sleeping sickness (Hoop Pine curse) as a reprisal against offenders of tribal law, tribal codes, enemies or bad spiritual influences. The ritual coincided with the bone pointing procedure common among Aboriginal tribes throughout Australia. |

| # | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name/word | Pronounced | Synonyms | Dialect | Meaning |

| 1 | ||||

| Jullum | Jul-lum | Jellum | Fish. | |

| 2 | ||||

| Ngumagal | Ngu-ma-gal | Goanna. | ||

| 3 | ||||

| Yabbra | Yab-bra | Bird. | ||

| 4 | ||||

| Wudgie-Wudgie | Wud-gie-Wud-gie | Red Cedar. |

See also

- Bundjalung people

- Bundjalung Nation Timeline

- Dirawong

- List of Aboriginal languages of New South Wales

References

- Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Bandjalangic". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/band1339.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Terry., Crowley (1978). The middle Clarence dialects of Bandjalang. Smythe, W. E.. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. pp. 252. ISBN 0855750650. OCLC 6041138. https://archive.org/details/middleclarencedi0000crow/page/252.

- ↑ Bowern, Claire. 2011. "How Many Languages Were Spoken in Australia?", Anggarrgoon: Australian languages on the web, 23 December 2011 (corrected 6 February 2012)

- ↑ "Census 2016, Language spoken at home by Sex (SA2+)" (in en-au). ABS. http://stat.data.abs.gov.au/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=ABS_C16_T09_SA.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 C., Sharpe, Margaret (2005). "Yugambeh–Bundjalung Dialects". Grammar and texts of the Yugambeh–Bundjalung dialect chain in eastern Australia. Muenchen: Lincom Europa. ISBN 3895867845. OCLC 62185149.

- ↑ "Arakwal People of Byron Bay » Blog Archive » About Us". http://arakwal.com.au/about-us/.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Terry., Crowley (1978). The middle Clarence dialects of Bandjalang. Smythe, W. E.. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. ISBN 0855750650. OCLC 6041138. https://archive.org/details/middleclarencedi0000crow.

- ↑ "Gidabal grammar and dictionary". 24 January 2013. https://www.sil.org/resources/publications/entry/2971.

- ↑ Cunningham, M. C (1969) (in en). A description of the Yugumbir dialect of Bandjalang. St. Lucia ; [Brisbane] : University of Queensland Press. https://trove.nla.gov.au/version/39789468.

- ↑ "The Minyung; The speech and the speakers. A study in Australian Aboriginal Philology by the Rev Hugh Livingstone Formerly a Presbyterian Minister at Lismore, New South Wales.". http://spencerandgillen.net/objects/50ce72f6023fd7358c8a9607.

- ↑ Crowley, Terry; Smythe, W. E; Studies, Australian Institute of Aboriginal; Crowley, Terry (1978) (in en). The middle Clarence dialects of Bandjalang. Canberra Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. ISBN 0855750650. https://archive.org/details/middleclarencedi0000crow.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 Sharpe, Margaret C. (2005). Grammar and Texts of the Yugambeh-Bundjalung Dialect Chain in Eastern Australia. Muenchen, Germany: LINCOM. pp. 180. ISBN 3-89586-784-5.

- ↑ C., Sharpe, Margaret (2005). Grammar and texts of the Yugambeh-Bundjalung dialect chain in Eastern Australia. Muenchen: Lincom Europa. ISBN 3895867845. OCLC 62185149.

- ↑ "Bundjalung Settlement and Migration (subscription required)" (in en). Aboriginal History (Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies) 9: 101–124. 1985. https://search.informit.com.au/documentSummary;dn=057737298952193;res=IELAPA. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- Bibliography

- Crowley, Terry (1978). The Middle Clarence dialects of Bundjalung. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

- Cunningham, Margaret C. (1969). "A description of the Yugumbir dialect of Bundjalung". University of Queensland Papers, Faculty of Arts 1 (8).

- Geytenbeek, Brain B. (1964). "Morphology of the regular verbs of Gidabul". Papers on the Languages of the Australian Aborigines.

- Geytenbeek, Brian B.; Getenbeek, Helen (1971). Gidabal grammar and dictionary. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. ISBN 9780855750190. https://archive.org/details/gidabalgrammardi0000geyt.

- Geytenbeek, Helen (1964). Personal pronouns of Gidabul.

- Holmer, Nils M. (1971). Notes on the Bundjalung Dialect. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

- Sharpe, Margaret C. (1994). An all-dialect dictionary of Bunjalung, an Australian language no longer in general use.

External links

- Bibliography of Bundjalung language and people resources, at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

- Bibliography of Arakwal language and people resources, at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies

|