Spiric section

In geometry, a spiric section, sometimes called a spiric of Perseus, is a quartic plane curve defined by equations of the form

Equivalently, spiric sections can be defined as bicircular quartic curves that are symmetric with respect to the x and y-axes. Spiric sections are included in the family of toric sections and include the family of hippopedes and the family of Cassini ovals. The name is from σπειρα meaning torus in ancient Greek.[1]

A spiric section is sometimes defined as the curve of intersection of a torus and a plane parallel to its rotational symmetry axis. However, this definition does not include all of the curves given by the previous definition unless imaginary planes are allowed.

Spiric sections were first described by the ancient Greek geometer Perseus in roughly 150 BC, and are assumed to be the first toric sections to be described. The name spiric is due to the ancient notation spira of a torus.,[2][3]

Equations

Start with the usual equation for the torus:

Interchanging y and z so that the axis of revolution is now on the xy-plane, and setting z=c to find the curve of intersection gives

In this formula, the torus is formed by rotating a circle of radius a with its center following another circle of radius b (not necessarily larger than a, self-intersection is permitted). The parameter c is the distance from the intersecting plane to the axis of revolution. There are no spiric sections with c > b + a, since there is no intersection; the plane is too far away from the torus to intersect it.

Expanding the equation gives the form seen in the definition

where

In polar coordinates this becomes

or

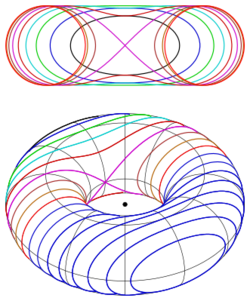

Spiric sections on a spindle torus

Spiric sections on a spindle torus, whose planes intersect the spindle (inner part), consist of an outer and an inner curve (s. picture).

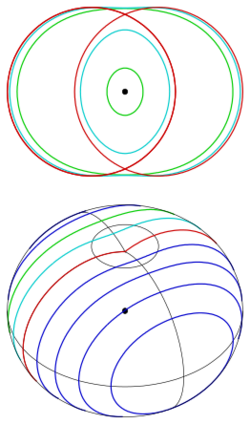

Spiric sections as isoptics

Isoptics of ellipses and hyperbolas are spiric sections. (S. also weblink The Mathematics Enthusiast.)

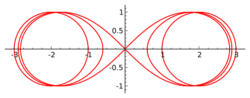

Examples of spiric sections

Examples include the hippopede and the Cassini oval and their relatives, such as the lemniscate of Bernoulli. The Cassini oval has the remarkable property that the product of distances to two foci are constant. For comparison, the sum is constant in ellipses, the difference is constant in hyperbolae and the ratio is constant in circles.

References

- Weisstein, Eric W.. "Spiric Section". http://mathworld.wolfram.com/SpiricSection.html.

- MacTutor history

- 2Dcurves.com description

- MacTutor biography of Perseus

- The Mathematics Enthusiast Number 9, article 4

- Specific

- ↑ Brieskorn, Egbert; Knörrer, Horst (1986). Plane algebraic curves. Modern Birkhäuser Classics. Birkhäuser/Springer Basel AG. p. 16. doi:10.1007/978-3-0348-5097-1. ISBN 978-3-0348-0492-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=qsDzBwAAQBAJ&pg=PA16. The word σπειρα originally meant a coil of rope, and came to refer to the base of a column, which for certain orders of column was shaped as a torus: see Yates, James (1875). "Spira". in Smith, William. A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/secondary/SMIGRA*/Spira.html.

- ↑ John Stillwell: Mathematics and Its History, Springer-Verlag, 2010, ISBN 978-1-4419-6053-5, p. 33.

- ↑ Wilbur R. Knorr: The Ancient Tradition of Geometric Problems, Dover-Publ., New York, 1993, ISBN 0-486-67532-7, p. 268 .

|