Terrain

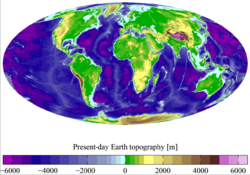

Terrain or relief (also topographical relief) involves the vertical and horizontal dimensions of land surface. The term bathymetry is used to describe underwater relief, while hypsometry studies terrain relative to sea level. The Latin word terra (the root of terrain) means "earth."

In physical geography, terrain is the lay of the land. This is usually expressed in terms of the elevation, slope, and orientation of terrain features. Terrain affects surface water flow and distribution. Over a large area, it can affect weather and climate patterns.

Importance

The understanding of terrain is critical for many reasons:

- The terrain of a region largely determines its suitability for human settlement: flatter alluvial plains tend to have better farming soils than steeper, rockier uplands.[1]

- In terms of environmental quality, agriculture, hydrology and other interdisciplinary sciences;[2] understanding the terrain of an area assists the understanding of watershed boundaries, drainage characteristics,[3] drainage systems, groundwater systems, water movement, and impacts on water quality. Complex arrays of relief data are used as input parameters for hydrology transport models (such as the Storm Water Management Model or DSSAM Models) to allow prediction of river water quality.

- Understanding terrain also supports soil conservation, especially in agriculture. Contour ploughing is an established practice enabling sustainable agriculture on sloping land; it is the practice of ploughing along lines of equal elevation instead of up and down a slope.

- Terrain is militarily critical because it determines the ability of armed forces to take and hold areas, and move troops and material into and through areas. An understanding of terrain is basic to both defensive and offensive strategy. The military usage of "terrain" is very broad, encompassing not only landform but land use and land cover, surface transport infrastructure, built structures and human geography, and, by extension under the term human terrain, even psychological, cultural, or economic factors.[4]

- Terrain is important in determining weather patterns. Two areas geographically close to each other may differ radically in precipitation levels or timing because of elevation differences or a rain shadow effect.

- Precise knowledge of terrain is vital in aviation, especially for low-flying routes and maneuvers (see terrain collision avoidance) and airport altitudes. Terrain will also affect range and performance of radars and terrestrial radio navigation systems. Furthermore, a hilly or mountainous terrain can strongly impact the implementation of a new aerodrome and the orientation of its runways.

Relief

Relief (or local relief) refers specifically to the quantitative measurement of vertical elevation change in a landscape. It is the difference between maximum and minimum elevations within a given area, usually of limited extent.[5] A relief can be described qualitatively, such as a "low relief" or "high relief" plain or upland. The relief of a landscape can change with the size of the area over which it is measured, making the definition of the scale over which it is measured very important. Because it is related to the slope of surfaces within the area of interest and to the gradient of any streams present, the relief of a landscape is a useful metric in the study of the Earth's surface. Relief energy, which may be defined inter alia as "the maximum height range in a regular grid",[6] is essentially an indication of the ruggedness or relative height of the terrain.

Geomorphology

Geomorphology is in large part the study of the formation of terrain or topography. Terrain is formed by concurrent processes operating on the underlying geological structures over geological time:

- Geological processes: migration of tectonic plates, faulting and folding, mountain formation, volcanic eruptions, etc.

- Erosional processes: glacial, water, wind, chemical and gravitational (mass movement); such as landslides, downhill creep, flows, slumps, and rock falls.

- Extraterrestrial: meteorite impacts.

Tectonic processes such as orogenies and uplifts cause land to be elevated, whereas erosional and weathering processes wear the land away by smoothing and reducing topographic features.[7] The relationship of erosion and tectonics rarely (if ever) reaches equilibrium.[8][9][10] These processes are also codependent, however the full range of their interactions is still a topic of debate.[11][12][13]

Land surface parameters are quantitative measures of various morphometric properties of a surface. The most common examples are used to derive slope or aspect of a terrain or curvatures at each location. These measures can also be used to derive hydrological parameters that reflect flow/erosion processes. Climatic parameters are based on the modelling of solar radiation or air flow.

Land surface objects, or landforms, are definite physical objects (lines, points, areas) that differ from the surrounding objects. The most typical examples airlines of watersheds, stream patterns, ridges, break-lines, pools or borders of specific landforms.

Digital terrain model

See also

- Applications of global navigation satellite systems (GNSS)

- Cartographic relief depiction (2D relief map)

- Geographic information system (GIS)

- Geomorphometry

- Hypsometry

- Isostasy

- Physical terrain model

- Relief ratio

- Subterranea

- Terrain awareness and warning system

- Terrane

- Topography

References

- ↑ Dwevedi, Alka; Kumar, Promod; Kumar, Pravita; Kumar, Yogendra; Sharma, Yogesh K.; Kayastha, Arvind M. (January 1, 2017). Grumezescu, Alexandru Mihai. ed. "15 - Soil sensors: detailed insight into research updates, significance, and future prospects" (in en). New Pesticides and Soil Sensors (Academic Press): 561–594. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-804299-1.00016-3. ISBN 978-0-12-804299-1. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B9780128042991000163. Retrieved October 11, 2022.

- ↑ Baker, N.T.; Capel, P.D. (2011). "Environmental factors that influence the location of crop agriculture in the conterminous United States". U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2011–5108. U.S. Geological Survey. p. 72.

- ↑ Brush, L. M. (1961). Drainage basins, channels, and flow characteristics of selected streams in central Pennsylvania. Washington D.C.: U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 1–44. https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/0282f/report.pdf. Retrieved October 29, 2017.

- ↑ "Joint Publication 1-02". https://irp.fas.org/doddir/dod/jp1_02-april2010.pdf. "* "compartmentation ... [involves] areas bounded on at least two sides by terrain features such as woods..."

* "culture — A feature of the terrain that has been constructed by man. Included are such items as roads, buildings, and canals; boundary lines; and, in a broad sense, all names and legends on a map."

* "key terrain — Any locality, or area, the seizure or retention of which affords a marked advantage to either combatant."

* "terrain intelligence — Intelligence on the military significance of natural and manmade characteristics of an area."" - ↑ Summerfield, M.A. (1991). Global Geomorphology. Pearson. p. 537. ISBN 9780582301566. https://archive.org/details/globalgeomorphol0000summ.

- ↑ Bollig, Michael; Bubenzer, Olaf, eds (2009). African Landscapes: Interdisciplinary Approaches. Cologne: Springer. p. 48. ISBN 9780387786827. https://books.google.com/books?id=YzBNmiGS-7oC&dq=definition+of+%22relief+energy%22&pg=PA48.

- ↑ Strak, V.; Dominguez, S.; Petit, C.; Meyer, B.; Loget, N. (2011). "Interaction between normal fault slip and erosion on relief evolution; insights from experimental modelling". Tectonophysics 513 (1–4): 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.tecto.2011.10.005. Bibcode: 2011Tectp.513....1S. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00646966/file/preprint_Strak_2011.pdf.

- ↑ Gasparini, N.; Bras, R.; Whipple, K. (2006). "Numerical modeling of non–steady-state river profile evolution using a sediment-flux-dependent incision model. Special Paper". Geological Society of America 398: 127–141. doi:10.1130/2006.2398(08).

- ↑ Roe, G.; Stolar, D.; Willett, S. (2006). "Response of a steady-state critical wedge orogen to changes in climate and tectonic forcing. Special Paper". Geological Society of America 398: 227–239. doi:10.1130/2005.2398(13).

- ↑ Stolar, D.; Willett, S.; Roe, G. (2006). "Climatic and tectonic forcing of a critical orogen. Special Paper". Geological Society of America 398: 241–250. doi:10.1130/2006.2398(14).

- ↑ Wobus, C.; Whipple, K.; Kirby, E.; Snyder, N.; Johnson, J.; Spyropolou, K.; Sheehan, D. (2006). "Tectonics from topography: Procedures, promise, and pitfalls. Special Paper". Geological Society of America 398: 55–74. doi:10.1130/2006.2398(04).

- ↑ Hoth et al. (2006), pp. 201–225; Bonnet, Malavieille & Mosar (2007); King, Herman & Guralnik (2016), pp. 800–804

- ↑ University of Cologne (23 August 2016). "New insights into the relationship between erosion and tectonics in the Himalayas". https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/08/160823083555.htm.

Bibliography

- Bonnet, C.; Malavieille, J.; Mosar, J. (2007). "Interactions between tectonics, erosion, and sedimentation during the recent evolution of the Alpine orogen: Analogue modeling insights". Tectonics 26 (TC6016). doi:10.1029/2006TC002048. Bibcode: 2007Tecto..26.6016B. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00404424/file/ark%20_67375_WNG-7JRV7H29-M.pdf.

- Hoth, S.; Adam, J.; Kukowski, N.; Oncken, O. (2006). "Influence of erosion on the kinematics of bivergent orogens: Results from scaled sandbox simulations. Special Paper". Geological Society of America 398: 201–225. doi:10.1130/2006.2398(12).

- King, G.; Herman, F.; Guralnik, B. (2016). "Northward migration of the eastern himalayan syntaxis revealed by OSL thermochronometry". Science 353 (6301): 800–804. doi:10.1126/science.aaf2637. PMID 27540169. Bibcode: 2016Sci...353..800K.

Further reading

- Boots on the ground. On military terrain from the perspective of the combat soldier. By Derek Gregory

External links

|