Thomas–Fermi equation

In mathematics, the Thomas–Fermi equation for the neutral atom is a second order non-linear ordinary differential equation, named after Llewellyn Thomas and Enrico Fermi,[1][2] which can be derived by applying the Thomas–Fermi model to atoms. The equation reads

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{d^2y}{dx^2} = \frac{1}{\sqrt x} y^{3/2} }[/math]

subject to the boundary conditions[3]

- [math]\displaystyle{ y(0)=1, \quad \quad \begin{cases}y(\infty)=0 \quad \text{for neutral atoms}\\ y(x_0)=0 \quad \text{for positive ions}\\ y(x_1)-x_1y'(x_1)=0\quad \text{for compressed neutral atoms}\end{cases} }[/math]

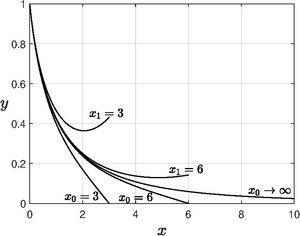

If [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] approaches zero as [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] becomes large, this equation models the charge distribution of a neutral atom as a function of radius [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math]. Solutions where [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] becomes zero at finite [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] model positive ions.[4] For solutions where [math]\displaystyle{ y }[/math] becomes large and positive as [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] becomes large, it can be interpreted as a model of a compressed atom, where the charge is squeezed into a smaller space. In this case the atom ends at the value of [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] for which [math]\displaystyle{ dy/dx=y/x }[/math].[5][6]

Transformations

Introducing the transformation [math]\displaystyle{ z=y/x }[/math] converts the equation to

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{1}{x^2}\frac{d}{dx}\left(x^2\frac{dz}{dx}\right) - z^{3/2}=0 }[/math]

This equation is similar to Lane–Emden equation with polytropic index [math]\displaystyle{ 3/2 }[/math] except the sign difference. The original equation is invariant under the transformation [math]\displaystyle{ x\rightarrow c x, \ y\rightarrow c^{-3} y }[/math]. Hence, the equation can be made equidimensional by introducing [math]\displaystyle{ y=x^{-3} u }[/math] into the equation, leading to

- [math]\displaystyle{ x^2 \frac{d^2u}{dx^2} - 6x\frac{du}{dx} + 12 u = u^{3/2} }[/math]

so that the substitution [math]\displaystyle{ x=e^t }[/math] reduces the equation to

- [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{d^2u}{dt^2} - 7\frac{du}{dt} +12 u = u^{3/2}. }[/math]

Treating [math]\displaystyle{ w =du/dt }[/math] as the dependent variable and [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] as the independent variable, we can reduce the above equation to

- [math]\displaystyle{ w \frac{dw}{du} - 7w = u^{3/2}-12 u. }[/math]

But this first order equation has no known explicit solution, hence, the approach turns to either numerical or approximate methods.

Sommerfeld's approximation

The equation has a particular solution [math]\displaystyle{ y_p(x) }[/math], which satisfies the boundary condition that [math]\displaystyle{ y\rightarrow 0 }[/math] as [math]\displaystyle{ x\rightarrow\infty }[/math], but not the boundary condition y(0)=1. This particular solution is

- [math]\displaystyle{ y_p(x) = \frac{144}{x^3}. }[/math]

Arnold Sommerfeld used this particular solution and provided an approximate solution which can satisfy the other boundary condition in 1932.[7] If the transformation [math]\displaystyle{ x=1/t, \ w = yt }[/math] is introduced, the equation becomes

- [math]\displaystyle{ t^4\frac{d^2w}{dt^2} = w^{3/2}, \quad w(0)=0, \ w(\infty)\sim t. }[/math]

The particular solution in the transformed variable is then [math]\displaystyle{ w_p(t)= 144 t^4 }[/math]. So one assumes a solution of the form [math]\displaystyle{ w=w_p(1+\alpha t^\lambda) }[/math] and if this is substituted in the above equation and the coefficients of [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] are equated, one obtains the value for [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math], which is given by the roots of the equation [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda^2 + 7\lambda -6=0 }[/math]. The two roots are [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda_1 = 0.772, \ \lambda_2 = -7.772 }[/math], where we need to take the positive root to avoid the singularity at the origin. This solution already satisfies the first boundary condition ([math]\displaystyle{ w(0)=0 }[/math]), so, to satisfy the second boundary condition, one writes to the same level of accuracy for an arbitrary [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ W=w_p(1+\beta t^\lambda)^n = [144 t^3(1+\beta t^\lambda)^n]t. }[/math]

The second boundary condition will be satisfied if [math]\displaystyle{ 144t^3(1+\beta t^\lambda)^n = 144 t^3 \beta^n t^{\lambda n}(1+\beta^{-1}t^{-\lambda})^n\sim 1 }[/math] as [math]\displaystyle{ t\rightarrow\infty }[/math]. This condition is satisfied if [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda n + 3 =0, \ 144 \beta^n =1 }[/math] and since [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda_1\lambda_2=-6 }[/math], Sommerfeld found the approximation as [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda = \lambda_1, \ n =-3/\lambda_1 = \lambda_2/2 }[/math]. Therefore, the approximate solution is

- [math]\displaystyle{ y(x) = y_p(x) \{1+[y_p(x)]^{\lambda_1/3}\}^{\lambda_2/2}. }[/math]

This solution predicts the correct solution accurately for large [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math], but still fails near the origin.

Solution near origin

Enrico Fermi[8] provided the solution for [math]\displaystyle{ x\ll 1 }[/math] and later extended by Edward B. Baker.[9] Hence for [math]\displaystyle{ x\ll 1 }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} y(x) = {} & 1 - Bx + \frac{1}{3} x^3 - \frac {2B} {15} x^4 + \cdots {} \\[6pt] & \cdots + x^{3/2} \left[\frac 4 3 - \frac{2B} 5 x + \frac{3B^2}{70} x^2 + \left(\frac{2}{27} + \frac{B^3}{252}\right) x^3 + \cdots\right] \end{align} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ B\approx 1.588071 }[/math].[10][11]

It has been reported by Salvatore Esposito[12] that the Italian physicist Ettore Majorana found in 1928 a semi-analytical series solution to the Thomas–Fermi equation for the neutral atom, which however remained unpublished until 2001. Using this approach it is possible to compute the constant B mentioned above to practically arbitrarily high accuracy; for example, its value to 100 digits is [math]\displaystyle{ B = 1.588 071 022 611 375 312 718 684 509 423 950 109 452 746 621 674825616765677418166551961154309262332033970138428665 }[/math].

References

- ↑ Davis, Harold Thayer. Introduction to nonlinear differential and integral equations. Courier Corporation, 1962.

- ↑ Bender, Carl M., and Steven A. Orszag. Advanced mathematical methods for scientists and engineers I: Asymptotic methods and perturbation theory. Springer Science & Business Media, 2013.

- ↑ Landau, L. D., & Lifshitz, E. M. (2013). Quantum mechanics: non-relativistic theory (Vol. 3). Elsevier. Page. 259-263.

- ↑ pp. 9-12, N. H. March (1983). "1. Origins – The Thomas–Fermi Theory". In S. Lundqvist and N. H. March. Theory of The Inhomogeneous Electron Gas. Plenum Press. ISBN:978-0-306-41207-3.

- ↑ March 1983, p. 10, Figure 1.

- ↑ p. 1562,Feynman, R. P.; Metropolis, N.; Teller, E. (1949-05-15). "Equations of State of Elements Based on the Generalized Fermi-Thomas Theory". Physical Review (American Physical Society (APS)) 75 (10): 1561–1573. doi:10.1103/physrev.75.1561. ISSN 0031-899X. Bibcode: 1949PhRv...75.1561F. http://authors.library.caltech.edu/3519/1/FEYpr49a.pdf.

- ↑ Sommerfeld, A. "Integrazione asintotica dell’equazione differenziale di Thomas–Fermi." Rend. R. Accademia dei Lincei 15 (1932): 293.

- ↑ Fermi, E. (1928). "Eine statistische Methode zur Bestimmung einiger Eigenschaften des Atoms und ihre Anwendung auf die Theorie des periodischen Systems der Elemente" (in de). Zeitschrift für Physik (Springer Science and Business Media LLC) 48 (1–2): 73–79. doi:10.1007/bf01351576. ISSN 1434-6001. Bibcode: 1928ZPhy...48...73F.

- ↑ Baker, Edward B. (1930-08-15). "The Application of the Fermi-Thomas Statistical Model to the Calculation of Potential Distribution in Positive Ions". Physical Review (American Physical Society (APS)) 36 (4): 630–647. doi:10.1103/physrev.36.630. ISSN 0031-899X. Bibcode: 1930PhRv...36..630B.

- ↑ Comment on: “Series solution to the Thomas–Fermi equation” [Phys. Lett. A 365 (2007) 111], Francisco M.Fernández, Physics Letters A 372, 28 July 2008, 5258-5260, doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2008.05.071.

- ↑ The analytical solution of the Thomas-Fermi equation for a neutral atom, G I Plindov and S K Pogrebnya, Journal of Physics B: Atomic and Molecular Physics 20 (1987), L547, doi:10.1088/0022-3700/20/17/001.

- ↑ Esposito, Salvatore (2002). "Majorana solution of the Thomas-Fermi equation". American Journal of Physics 70 (8): 852–856. doi:10.1119/1.1484144. Bibcode: 2002AmJPh..70..852E.

|