Trapdoor function

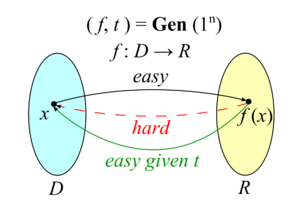

In theoretical computer science and cryptography, a trapdoor function is a function that is easy to compute in one direction, yet difficult to compute in the opposite direction (finding its inverse) without special information, called the "trapdoor". Trapdoor functions are a special case of one-way functions and are widely used in public-key cryptography.[2]

In mathematical terms, if f is a trapdoor function, then there exists some secret information t, such that given f(x) and t, it is easy to compute x. Consider a padlock and its key. It is trivial to change the padlock from open to closed without using the key, by pushing the shackle into the lock mechanism. Opening the padlock easily, however, requires the key to be used. Here the key t is the trapdoor and the padlock is the trapdoor function.

An example of a simple mathematical trapdoor is "6895601 is the product of two prime numbers. What are those numbers?" A typical "brute-force" solution would be to try dividing 6895601 by many prime numbers until finding the answer. However, if one is told that 1931 is one of the numbers, one can find the answer by entering "6895601 ÷ 1931" into any calculator. This example is not a sturdy trapdoor function – modern computers can guess all of the possible answers within a second – but this sample problem could be improved by using the product of two much larger primes.

Trapdoor functions came to prominence in cryptography in the mid-1970s with the publication of asymmetric (or public-key) encryption techniques by Diffie, Hellman, and Merkle. Indeed, (Diffie Hellman) coined the term. Several function classes had been proposed, and it soon became obvious that trapdoor functions are harder to find than was initially thought. For example, an early suggestion was to use schemes based on the subset sum problem. This turned out rather quickly to be unsuitable.

As of 2004[update], the best known trapdoor function (family) candidates are the RSA and Rabin families of functions. Both are written as exponentiation modulo a composite number, and both are related to the problem of prime factorization.

Functions related to the hardness of the discrete logarithm problem (either modulo a prime or in a group defined over an elliptic curve) are not known to be trapdoor functions, because there is no known "trapdoor" information about the group that enables the efficient computation of discrete logarithms.

A trapdoor in cryptography has the very specific aforementioned meaning and is not to be confused with a backdoor (these are frequently used interchangeably, which is incorrect). A backdoor is a deliberate mechanism that is added to a cryptographic algorithm (e.g., a key pair generation algorithm, digital signing algorithm, etc.) or operating system, for example, that permits one or more unauthorized parties to bypass or subvert the security of the system in some fashion.

Definition

A trapdoor function is a collection of one-way functions { fk : Dk → Rk } (k ∈ K), in which all of K, Dk, Rk are subsets of binary strings {0, 1}*, satisfying the following conditions:

- There exists a probabilistic polynomial time (PPT) sampling algorithm Gen s.t. Gen(1n) = (k, tk) with k ∈ K ∩ {0, 1}n and tk ∈ {0, 1}* satisfies | tk | < p (n), in which p is some polynomial. Each tk is called the trapdoor corresponding to k. Each trapdoor can be efficiently sampled.

- Given input k, there also exists a PPT algorithm that outputs x ∈ Dk. That is, each Dk can be efficiently sampled.

- For any k ∈ K, there exists a PPT algorithm that correctly computes fk.

- For any k ∈ K, there exists a PPT algorithm A s.t. for any x ∈ Dk, let y = A ( k, fk(x), tk ), and then we have fk(y) = fk(x). That is, given trapdoor, it is easy to invert.

- For any k ∈ K, without trapdoor tk, for any PPT algorithm, the probability to correctly invert fk (i.e., given fk(x), find a pre-image x' such that fk(x' ) = fk(x)) is negligible.[3][4][5]

If each function in the collection above is a one-way permutation, then the collection is also called a trapdoor permutation.[6]

Examples

In the following two examples, we always assume that it is difficult to factorize a large composite number (see Integer factorization).

RSA assumption

In this example, the inverse of modulo (Euler's totient function of ) is the trapdoor:

If the factorization of is known, then can be computed. With this the inverse of can be computed , and then given , we can find . Its hardness follows from the RSA assumption.[7]

Rabin's quadratic residue assumption

Let be a large composite number such that , where and are large primes such that , and kept confidential to the adversary. The problem is to compute given such that . The trapdoor is the factorization of . With the trapdoor, the solutions of z can be given as , where . See Chinese remainder theorem for more details. Note that given primes and , we can find and . Here the conditions and guarantee that the solutions and can be well defined.[8]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Ostrovsky, pp. 6–9

- ↑ Bellare, M (June 1998). "Many-to-one trapdoor functions and their relation to public-key cryptosystems". Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO '98. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. 1462. pp. 283–298. doi:10.1007/bfb0055735. ISBN 978-3-540-64892-5.

- ↑ Pass's Notes, def. 56.1

- ↑ Goldwasser's lecture notes, def. 2.16

- ↑ Ostrovsky, pp. 6–10, def. 11

- ↑ Pass's notes, def 56.1; Dodis's def 7, lecture 1.

- ↑ Goldwasser's lecture notes, 2.3.2; Lindell's notes, p. 17, Ex. 1.

- ↑ Goldwasser's lecture notes, 2.3.4.

References

- Diffie, W.; Hellman, M. (1976), "New directions in cryptography", IEEE Transactions on Information Theory 22 (6): 644–654, doi:10.1109/TIT.1976.1055638, https://www-ee.stanford.edu/~hellman/publications/24.pdf

- Pass, Rafael, A Course in Cryptography, https://www.cs.cornell.edu/courses/cs4830/2010fa/lecnotes.pdf, retrieved 27 November 2015

- Goldwasser, Shafi, Lecture Notes on Cryptography, https://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~mihir/papers/gb.pdf, retrieved 25 November 2015

- Ostrovsky, Rafail, Foundations of Cryptography, https://web.cs.ucla.edu/~rafail/PUBLIC/OstrovskyDraftLecNotes2010.pdf, retrieved 27 November 2015

- Dodis, Yevgeniy, Introduction to Cryptography Lecture Notes (Fall 2008), http://www.cs.nyu.edu/courses/fall08/G22.3210-001/index.html, retrieved 17 December 2015

- Lindell, Yehuda, Foundations of Cryptography, http://u.cs.biu.ac.il/~lindell/89-856/complete-89-856.pdf, retrieved 17 December 2015

|