Unsolved:Clean Wehrmacht

The myth of the Clean Wehrmacht (German: Saubere Wehrmacht), Clean Wehrmacht legend (Legende von der sauberen Wehrmacht), or Wehrmacht's "clean hands"[1][2] is the myth that the Wehrmacht was an apolitical organization along the lines of its predecessor, the Reichswehr, and was largely innocent of Nazi Germany's war crimes and crimes against humanity, behaving in a similar manner to the armed forces of the Western Allies. This narrative is false, as shown by the Wehrmacht's own documents, such as the records detailing the executions of Red Army commissars by frontline divisions, in violation of the laws of war. While the Wehrmacht largely treated British and American POWs in accordance with these laws (giving the myth plausibility in the West), they routinely enslaved, starved, shot, or otherwise abused and murdered Polish, Soviet, and Yugoslav civilians and prisoners of war. Wehrmacht units also participated in the mass murder of Jews and others.[3]

The myth began in the late 1940s, with former Wehrmacht officers and veterans' groups looking to evade guilt, and a few German veterans' associations and various far-right authors and publishers in Germany and abroad continue to promote such a view. Modern defenders often downplay or deny the Wehrmacht's involvement in the Holocaust, largely ignore the German persecution of Soviet prisoners of war, and emphasise the role of the SS and the civil administration in the atrocities committed.

The Waffen-SS, in turn, attempted to benefit from the clean Wehrmacht myth by their veterans declaring the organisation to have virtually been branch of the latter, and to have fought as "honourably" as it. Its veteran organisation, HIAG, attempted to cultivate a myth of their soldiers having been "Soldiers like any other".[4]

War of extermination

In the eyes of the Nazis, the war against the Soviet Union would be a war of annihilation (Vernichtungskrieg).[5] The racial policy of Nazi Germany viewed the Soviet Union (and all of Eastern Europe) as populated by non-Aryan Untermenschen ("sub-humans"), ruled by "Jewish Bolshevik conspirators".[6] Accordingly, it was stated Nazi policy to kill, deport, or enslave the majority of Russian and other Slavic populations according to the Generalplan Ost ("General Plan for the East").[6] The plan consisted of the Kleine Planung ("Small Plan") and the Große Planung ("Large Plan"), which covered actions to be taken during the war and actions to be implemented after the war was won, respectively.[7] The plans entailed killing the vast majority of the native population among the nations it would be implemented through starvation and deportations.

Before and during the invasion of the Soviet Union, German troops were heavily indoctrinated with anti-Bolshevik, anti-Semitic and anti-Slavic propaganda.[8] Following the invasion, Wehrmacht officers told their soldiers to target people who were described as "Jewish Bolshevik subhumans", the "Mongol hordes", the "Asiatic flood" and the "Red beast".[9] Many German troops viewed the war in Nazi terms and regarded their Soviet enemies as sub-human.[10] A speech given by General Erich Hoepner indicates the disposition of Operation Barbarossa and the Nazi racial plan, as he informed the 4th Panzer Group that the war against the Soviet Union was "an essential part of the German people's struggle for existence" (Daseinskampf), and stated, "the struggle must aim at the annihilation of today's Russia and must therefore be waged with unparalleled harshness."[11]

Foundation

The Potsdam Conference held by the Soviet Union, United Kingdom and United States from 17 July to 2 August 1945 largely determined the occupation policies that the defeated country was to face. These included demilitarisation, denazification, democratization and decentralization. The Allies' often crude and ineffective implementation caused the local population to dismiss the process as a "noxious mixture of moralism and 'victors' justice'".[12]

For those in the Western zones of occupation, the arrival of the Cold War undermined the demilitarization process by seemingly justifying a major part of Hitler's foreign policies — the "fight against Soviet bolshevism".[13] In 1950, after the outbreak of the Korean War, it became clear to the Americans that a German army would have to be revived to help face off against the Soviet Union. Both American and West German politicians were faced with the prospect of rebuilding the armed forces of the Federal Republic.[14]

Himmerod memorandum

From 5 to 9 October 1950, a group of former senior officers, at the behest of Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, met in secret at Himmerod Abbey (hence the memorandum's name) to discuss West Germany's rearmament. The participants were divided into several subcommittees that focused on the political, ethical, operational and logistical aspects of the future armed forces.[15] The "internal structure" working group was headed by General Hermann Foertsch, who in the 1930s had been a protege of Field Marshal Walter von Reichenau, one of the most ardent National Socialists in the Wehrmacht, and would go on to become one of Adenauer's advisers on defense.[16]

The resulting memorandum included a summary of the discussions at the conference and bore the name "Memorandum on the Formation of a German Contingent for the Defense of Western Europe within the framework of an International Fighting Force". It was intended as both a planning document and as a basis of negotiations with the Western Allies.[15]

The participants of the conference were convinced that no future German army would be possible without the historical rehabilitation of the Wehrmacht. Thus, the memorandum included these key demands:

- All German soldiers convicted as war criminals would be released;

- The "defamation" of the German soldier, including those of the Waffen-SS, would have to cease;

- The "measures to transform both domestic and foreign public opinion" with regards to the German military would need to be taken.[14]

Adenauer accepted these propositions and in turn advised the representatives of the three Western powers that German armed forces would not be possible as long as German soldiers remained in custody. To accommodate the West German government, the Allies commuted a number of war crimes sentences.[14]

Public opinion

A public declaration from Dwight D. Eisenhower followed in January 1951, stating that there was "a real difference between the German soldier and Hitler and his criminal group". Chancellor Adenauer made a similar statement in a Bundestag debate on the Article 131 of the Grundgesetz, West Germany's provisional constitution. He stated that the German soldier fought honorably, as long as he "had not been guilty of any offense".[16] Article 231 expressly declared that all who served in the military and the civil service before 1945 were entitled to their full pensions, a measure that did not touch directly upon the memory of the past, but did suggest the majority of those who served the National Socialist regime were honorable people who deserved their pensions.[17] These declarations laid the foundation of the myth of the "clean Wehrmacht" that reshaped the West's perception of the German war effort.[1]

In the immediate aftermath of World War II, there was much sympathy in Germany with those accused of war crimes and in the late 1940s and 1950s there was a flood of polemical books and essays demanding freedom for the "so-called 'war criminals'", the very phrasing of which implied that those convicted of war crimes were in fact innocent.[18] The German historian Norbert Frei wrote that the widespread demand for freedom for the "so-called war criminals" was "an indirect admission of the entire society's enmeshment in National Socialism"; the war crimes trials were a painful reminder of the nature of the regime that many ordinary people had identified with, and in this context, there was an overwhelming demand for the rehabilitation of the Wehrmacht.[19] This is in part because the Wehrmacht could trace its descent back to the Prussian Army and before that to the army founded in 1640 by Frederich Wilhelm, the "Great Elector" of Brandenburg, making it an institution deeply rooted in German history, which presented problems for those who wanted to portray the Nazi era as a "freakish aberration" from the course of German history. In part, there were so many Germans who served in the Wehrmacht or who had family members who served in the Wehrmacht that there was a widespread demand to have a version of the past that allowed them to "...honor the memory of their fallen comrades and to find meaning in the hardships and personal sacrifice of their own military service".[20]

Denial of responsibility

After penalties were imposed in the immediate postwar period as part of the denazification process in the late 1940s to the early 1950s, the Federal Republic of Germany's population and politicians sharply criticized the practice of "victor's justice" and the theory of collective guilt (in the opinion of historian Norbert Frei, it was never the Allies' intention to impose collective punishment). Thus, the German Federal Parliament began to enact amnesty laws under which many war criminals saw their sentences commuted.[clarification needed]

Political climate

The changing political climate in the immediate post-war period aided in the creation of the image of a "clean Wehrmacht", according to which, unlike the criminal killings carried out by police and SS groups, the Wehrmacht had fought fairly under the provisions of the international law of war without involvement in the crimes of the Nazi regime.[21] Until the 1980s and 1990s, there was something of a division of labor among historians; military historians writing the history of World War II focused on the campaigns and battles of the Wehrmacht and treated the genocidal policies of the Nazi regime in passing, if at all,[22] while historians of the Holocaust and of the occupation policies of Nazi Germany largely avoided writing about the Wehrmacht.[22] This was not the result of a conspiracy, but rather due to the training of historians for different fields. Military historians tended to focus on battles and campaigns to the exclusion of everything else, and as a result, most military historians were not interested in the Wehrmacht's role in occupation policies in the areas it had conquered.[23]

The subject of the Holocaust was largely avoided outside of Israel in the 1950s and 1960s.[23] The governments of Britain, the United States, France, Canada, and other countries had either imposed restrictions on Jewish refugees in the 1930s or in the case of Canada barred all Jewish refugees outright, and most did not wish to be reminded that many of the Jews turned away in the 1930s were subsequently killed in the Holocaust. As such, historians outside of Germany were not much interested in the Holocaust and there were almost no studies done of the Wehrmacht's involvement in the "Final Solution to the Jewish Question" as the subject of the "Final Solution" itself attracted almost no interest until the 1960s.[24] The Austrian-born American historian Raul Hilberg found that in the 1950s, few in the United States wanted to hear about the Holocaust. Successive publishers rejected his later critically acclaimed 1961 book The Destruction of the European Jews, telling him that nobody in America was interested in the topic.[25]

Memoirs and historical studies

Former German officers published their memoirs and historical studies, which also contributed to the myth. The chief architect of this body of work was the former chief of the Oberkommando des Heeres, Franz Halder. He informally supervised the work of other officers who, during and since their prisoner-of-war captivity, had worked in the Operational History (German) Section of the U.S. Army Historical Division and had exclusive access to the captured German war archives stored in the United States.[26]

In a case of the vanquished writing history, starting in 1947, the U.S. Army Historical Division assembled a large group of former Wehrmacht generals under the leadership of Halder to write a multi-volume history of the Eastern Front so that U.S. Army officers could learn about the tactics of the Red Army, albeit as the Germans perceived them.[27] The work of the Halder committee, which was a quasi-official history, was extremely influential on the memory of the war beginning in the 1950s, and the picture that the Halder committee drew of a highly professional, apolitical Wehrmacht that had nothing to do with war crimes, was widely accepted by historians.[27]

The German historian Wolfram Wette described Halder as having a "decisive influence in West Germany in the 1950s and 1960s on the way the history of the Second World War was written, by virtue of the knowledge he had amassed working on the studies assembled by the Historical Division, which he shared with both professional historians and interested amateurs and veterans".[28] Other Wehrmacht leaders like Erich von Manstein and Heinz Guderian published best-selling memoirs that depicted the Wehrmacht as victims of Hitler rather than as his followers; a group of professional, apolitical officers who were quietly opposed to National Socialism who were led into the abyss by their deranged Führer through no fault of their own.[29] Given this picture, discussion of war crimes by the Wehrmacht was completely avoided as it would damage the picture of the Wehrmacht as "victims" of Hitler.[30]

Trial of Erich von Manstein

Captain Basil Liddell Hart, was an influential British military historian who endorsed the "clean Wehrmacht" myth, writing with admiration that the Wehrmacht had been the mightiest war machine ever built and that it would have won the war if only Hitler had not interfered with the conduct of operations.[29] Between 1949 and 1953, Liddell Hart was deeply involved in a campaign urging the release of Manstein after a British military court convicted him of war crimes on the Eastern Front, which he called a gross miscarriage of justice.[31] The trial of Manstein was a turning point in the British people's perception of the Wehrmacht; Manstein's lawyer, the Labour MP Reginald Paget, waged a well-oiled and energetic public relations campaign for amnesty for his client, enlisting many politicians and celebrities in the process.[32]

One celebrity who joined Paget's campaign, the left-wing philosopher Bertrand Russell, wrote in a 1949 essay that the enemy of the time was the Soviet Union, not Germany, and given the way in which Manstein was a hero to the German people, that it was necessary for the wartime Western Allies to free him for the needs of the Cold War.[31] Liddell Hart joined Paget's campaign for freedom for Manstein, and as Liddell Hart often wrote on military affairs in British newspapers, he played a key role in winning Manstein his freedom in May 1953.[31] Given Liddell Hart's general sympathy with the Wehrmacht, he depicted it in his books and essays as an apolitical force that had nothing to do with the crimes of the National Socialist regime, a subject that did not much interest Liddell Hart in the first place.[29]

In arguing for Manstein, Paget had made mutually exclusive contradictory arguments. Namely while knowing nothing of Nazi crimes, Manstein and other Wehrmacht officers simultaneously opposed the Nazi crimes that they were supposedly unaware of.[33] Paget lost the Manstein case with the British military tribunal presided over by Lieutenant General Frank Simpson finding Manstein supported Hitler's "war of annihilation" against the Soviet Union, enforced the Commissar Order, and as commander of the 11th Army assisted Einsatzgruppe C with massacring Jews in the Ukraine, sentencing him to 18 years in prison for war crimes.[34]

The British historian Tom Lawson wrote that Paget was greatly helped by the fact that most of the British "Establishment" naturally sympathized with the traditional elites in Germany, seeing them as people much like themselves, and for members of the "Establishment" like Archbishop George Bell the mere fact that Manstein was a German Army officer and a Lutheran who went to church regularly "..was enough to confirm his opposition to the Nazi state and therefore the absurdity of the trial".[35] During and after the trial of Manstein, Paget denied that Operation Barbarossa was a "war of annihilation", down-playing the racist aspects of Barbarossa and the campaign to exterminate Soviet Jews as the supposed fonts of Communism, and instead argued that "the Wehrmacht displayed a large degree of restraint and discipline in circumstances of unimaginable cruelty".[36]

Wette wrote that most Anglo-American military historians had a strong admiration for the "professionalism" of the Wehrmacht, and tended to write about the Wehrmacht in a very admiring tone, largely accepting the version of history set out in the memoirs of former Wehrmacht leaders.[24] Wette suggested this "professional solidarity" had something with the fact that most military historians in the English-speaking world tended to be conservative former Army officers who had a natural sympathy with conservative former Wehrmacht officers, whom they saw as men much like themselves.[24] He suggested that this sympathy did not extend to Nazi Germany itself, but only the picture of a "professional" Wehrmacht committed to Prussian values that were allegedly inimical to Nazism, while displaying super-human courage and endurance against overwhelming odds, especially on the Eastern Front.[37]

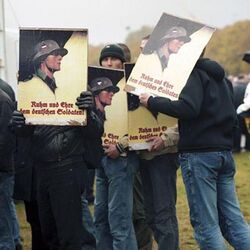

Jennifer Foray, in her 2010 study of the Wehrmacht occupation of the Netherlands, asserts that "Scores of studies published in the last few decades have demonstrated that the Wehrmacht's purported disengagement with the political sphere was an image carefully cultivated by commanders and foot soldiers alike, who, during and after the war, sought to distance themselves from the ideologically driven murder campaigns of the National Socialists."[38] Following the return of the last war prisoners from Soviet captivity, on 7 October 1955, 600 former members of the Wehrmacht and the Waffen-SS swore a public oath in the Friedland Barracks that received a strong media reaction:

Before the German people and the German dead and the Soviet Armed Forces, we swear that we have neither committed murder, nor defiled, nor plundered. If we have brought suffering and misery on other people, it was done according to the Laws of War.[39]

Debunking

In 2011, the Germany military historian Wolfram Wette called the "clean Wehrmacht" thesis a "collective perjury".[40] After the return of former Wehrmacht documents by the Western Allies to the Federal Republic of Germany,[41] it became clear through their evaluation that it was not possible to sustain the narrative any longer. Today, the extensive involvement of the Wehrmacht in numerous Nazi crimes is documented, such as the Commissar Order.[42]

While advocates of the thesis of a "clean Wehrmacht" were attempting to describe the Wehrmacht as independent of the Nazi ideology, and denying their war crimes or trying to put individual cases into perspective, more recent historical research from the 1980s and 1990s based on witness statements, court documents, letters from the front, personal diaries and other documents demonstrates the immediate and systematic involvement of the armed forces in many massacres and war crimes, especially in Eastern and Southeastern Europe, and the Holocaust.[42]

In the 1990s and 2000s, two exhibitions by the Hamburg Institute for Social Research exposed these crimes to a wider audience and focused on the hostilities as a German-Soviet extermination war. The historian Christian Hartmann found in 2009 that "no one needs to expose the deceptive myth of the 'clean' Wehrmacht any further. Their guilt is so overwhelming that any discussion about it is superfluous."[43]

In 2000, historian Truman Anderson identified a new scholarly consensus centering around the "recognition of the Wehrmacht's affinity for key features of the National Socialist world view, especially for its hatred of communism and its anti-semitism".[44] Similarly, Ben Shepherd writes that "Most historians now acknowledge the scale of Wehrmacht involvement in the crimes of the Third Reich", but maintains that "there nevertheless remains considerable debate as to the relative importance of the roles which ideology, careerism, ruthless military utilitarianism, and pressure of circumstances played in shaping Wehrmacht conduct."[45] Finally, in his last book, he points out how the "German army's moral failure and military failure" were always reinforcing each other, whether at a time of success after the victory over France, or in the days of defeat and destruction.[46]

Commissar Order

German historian Felix Römer has studied the implementation of the Commissar Order by the Wehrmacht, publishing his findings in 2008 as Der Kommissarbefehl. Wehrmacht und NS-Verbrechen an der Ostfront 1941/42 [The Commissar Order: The Wehrmacht and the Nazi Crimes on the Eastern Front, 1941–1942]. It was the first complete account of the implementation of the order by the combat formations of the Wehrmacht. Römer's research showed that 116 out of 137 German divisions on the Eastern Front filed reports detailing the killing of the Red Army's political commissars. In total, at least 3430 were murdered by the regular troops (and not by the SS) according to the order until May 1942, possibly up to 4,000 men.[47]

Römer finds that the records "prove that Hitler's generals had executed his murderous orders without scruples or hesitations", thereby shattering vestiges of the myth of the clean Wehrmacht. Historian Wolfram Wette, reviewing the book, notes that the sporadic objections to the order were not fundamental, but rather driven by military necessity and that the cancellation of the order in 1942 was "not a return to morality, but an opportunistic course correction". Wette concludes: "The Commissar Order, which has always had a particularly strong influence on the image of the Wehrmacht because of its obviously criminal character, has finally been clarified. Once again the observation has confirmed itself: the deeper the research penetrates into the military history, the gloomier the picture becomes."[48]

Participation in the Holocaust

American historian Waitman Wade Beorn has examined the complicity of the Wehrmacht in the crimes committed against Jews and other civilians in Belarus , from autumn 1941 to early in the subsequent winter, in his work Marching into Darkness: The Wehrmacht and the Holocaust in Belarus. The book investigates how so-called anti-partisan warfare was connected to the Holocaust via its ideological targeting of "Jewish-Bolsheviks". Beorn concludes that, because anti-semitic sentiment was lower in Belarus, the Army Group Centre Rear Area, compared to the territories of Army Group North and Army Group South Rear Areas, the army troops played a significantly larger role in direct persecution of Jews during the period that he studied.[49]

Beorn addresses other aspects of Wehrmacht crimes, including its support for the starvation policy of Nazi Germany, the Hunger Plan. He examines what he calls "the progressive complicity" of the Wehrmacht, highlighting the main developments that led to the escalation of violence, such as the Mogilev Conference in September 1941. Organised by the commander of the Army Group Centre Rear Area, it brought together the German Army, the SS and the Order Police commanders for an "exchange of experiences" and marked a dramatic escalation of violence against the civilian population.[50] The book looks at several military formations and how they responded to orders to commit genocide and other crimes against humanity. Beorn finds that those who refused were only lightly punished (or not punished at all), debunking the claims of German veterans that they had to participate under threat of death.[51]

Italian parallel

The "Clean Wehrmacht" myth parallels the emergence of a comparable narrative surrounding the participation of the Royal Italian Army during World War II. Emerging under the post-war republic, it was argued that "the Italians were decent people" (Italiani, brava gente) in contrast to the ideologically motivated and brutal Germans. In particular, it argued that the Italians had not participated in the Nazi persecution of Jews in occupied parts of Eastern Europe.[52][53] A notable example of the phenomenon in popular culture is the film Mediterraneo (1991), directed by Gabriele Salvatores.[52] This avoided "a public debate on collective responsibility, guilt and denial, repentance and pardon" but has recently been challenged by historians.[52]

Waffen-SS parallel

Analogus to the Wehrmacht Waffen-SS veterans and their organisation, HIAG, tried to portray the Waffen-SS as a clean fighting force, innocent of war crimes. HIAG argued that the Waffen-SS was the fourth branch of the Wehrmacht and had fought honourably, like it made out the Wehrmacht to have done, and that all crimes committed by the SS, which even HIAG could not deny, had been carried out by the other, non-combat branches of the organisation. HIAG thereby combined the Waffen-SS into the myth of the "Clean Wehrmacht", something former Wehrmacht officials were not particularly comfortable about.[4] This claim was not particularly successful as the Waffen-SS had been declared a criminal organisation after the war and, apart from the war crimes it committed, almost 60,000 of its members had served at some stage as concentration camp guards or in Einsatzgruppen.[54] High level support from German post-war politicians like Konrad Adenauer and Franz-Josef Strauss led however to the myth of the Waffen-SS soldiers having been "Soldiers like any other".[55][4]

See also

- Nazism and the Wehrmacht

- Rommel myth

- Waffen-SS in popular culture

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wette 2007, pp. 236–238.

- ↑ Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 74–76.

- ↑ Urlich Herbert (2016): “Holocaust Research in Germany”, in Holocaust and Memory in Europe, edited by Thomas Schlemmer and Alan E. Steinweis, p. 39

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Wienand 2015, p. 39.

- ↑ Förster 1988, p. 21.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 & The Fatal Attraction of Adolf Hitler, 1989.

- ↑ Rössler & Schleiermacher 1996, pp. 270–274.

- ↑ Evans 1989, p. 59.

- ↑ Evans 1989, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Förster 2005, p. 127.

- ↑ Ingrao 2013, p. 140.

- ↑ Large 1987, pp. 79–80.

- ↑ Large 1987, p. 80.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Smelser & Davies 2008, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Abenheim 1989, pp. 53–54.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Wette 2007, p. 236.

- ↑ Wette 2007, p. 238.

- ↑ Wette 2007, p. 239.

- ↑ Wette 2007, p. 240-241.

- ↑ Wette 2007, p. 241-242.

- ↑ Norbert Frei: Deutsche Lernprozesse. NS-Vergangenheit und Generationenfolge. In: Derselbe: 1945 und wir. Das Dritte Reich im Bewußtsein der Deutschen. dtv, München 2009, S. 49.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Wette 2007, p. 257.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Wette 2007, p. 254.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Wette 2007, p. 230-231.

- ↑ Wette 2007, p. 276-277.

- ↑ Wolfram Wette: Die Wehrmacht. Feindbilder, Vernichtungskrieg, Legenden. S. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-7632-5267-3, S. 225–229.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Wette 2007, p. 251.

- ↑ Wette 2007, p. 345.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Wette 2007, p. 234-235.

- ↑ Wette 2007, p. 234.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Wette 2007, p. 226.

- ↑ Wette 2007, p. 224-225.

- ↑ Lawson 2006, p. 159.

- ↑ Wette 2007, p. 225-226.

- ↑ Lawson 2006, p. 159-160.

- ↑ Wette 2007, p. 225.

- ↑ Wette 2007, p. 230.

- ↑ Foray 2010, pp. 769–770.

- ↑ Quoted in Hans Reichelt, Die deutschen Kriegsheimkehrer. Was hat die DDR für sie getan? eastern edition, Berlin 2007

- ↑ Zähe Legenden. Interview mit Wolfram Wette, in: Die Zeit vom 1. Juni 2011, S. 22

- ↑ Vgl. Astrid M. Eckert: Kampf um die Akten: Die Westalliierten und die Rückgabe von deutschem Archivgut nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg. Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 2004.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Gerd R. Ueberschär: Die Legende von der sauberen Wehrmacht. In: Wolfgang Benz, Hermann Graml, Hermann Weiß (historian) (Eds.): Enzyklopädie des Nationalsozialismus. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-423-34408-1, S. 110f.

- ↑ Christian Hartmann: Wehrmacht im Ostkrieg. Front und militärisches Hinterland 1941/42. (= Quellen und Darstellungen zur Zeitgeschichte, Band 75) Oldenbourg, München 2009, ISBN 978-3-486-58064-8, S. 790.

- ↑ Anderson 2000, p. 325.

- ↑ Shepherd 2009, pp. 455–6.

- ↑ Shepherd 2016, p. 536.

- ↑ Kellerhoff 2016.

- ↑ Wette 2009.

- ↑ Shepherd 2015.

- ↑ Kühne 2015.

- ↑ Nelson 2014.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Petrusewicz, Marta (2004). "The hidden pages of contemporary Italian history: war crimes, war guilt and collective memory". Journal of Modern Italian Studies 9 (3): 269–70.

- ↑ Rodogno, Davide (2005). "Italiani brava gente? Fascist Italy’s Policy Toward the Jews in the Balkans, April 1941–July 1943". European History Quarterly 35 (2): 213–40.

- ↑ Wiederschein, Harald (21 July 2015). "Mythos Waffen-SS" (in German). Focus. https://www.focus.de/wissen/mensch/geschichte/zweiter-weltkrieg/militaerisch-unbedeutend-brutal-verbrecherisch-mythos-waffen-ss-hitlers-ueberschaetzte-elitetruppen_id_4826676.html.

- ↑ "WAFFEN-SS" (in German). Der Spiegel. 25 March 1964. http://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-46173314.html.

Bibliography

In English

- Abenheim, Donald (1989). Reforging the Iron Cross: The Search for Tradition in the West German Armed Forces. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691602479. http://press.princeton.edu/titles/4299.html.

- Anderson, Truman (July 2000). "Germans, Ukrainians and Jews: Ethnic Politics in Heeresgebiet Sud, June– December 1941". War in History 7 (3): 325–351. doi:10.1177/096834450000700304. http://wih.sagepub.com/content/7/3/325.short.

- Modern Genocide: The Definitive Resource and Document Collection. 1. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. 2014. ISBN 978-1-61069-363-9. http://www.abc-clio.com/ABC-CLIOCorporate/product.aspx?pc=A4051C.

- Blood, Phillip W. (2006). Hitler's Bandit Hunters: The SS and the Nazi Occupation of Europe. Potomac Books. ISBN 978-1597970211.

- Boog, Horst; Förster, Jürgen; Hoffmann, Joachim; Klink, Ernst; Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Ueberschär, Gerd R. (1998). Attack on the Soviet Union. Germany and the Second World War. IV. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-822886-4.

- Evans, Richard J. (1989). In Hitler's Shadow West German Historians and the Attempt to Escape the Nazi Past. New York: Pantheon. ISBN 978-0394576862.

- Foray, Jennifer (October 2010). "The 'Clean Wehrmacht' in the German-occupied Netherlands, 1940–5". Journal of Contemporary History 45 (4): 768–787. doi:10.1177/0022009410375178.

- Förster, Jürgen (Winter 1988). "Barbarossa Revisited: Strategy and Ideology in the East". Jewish Social Studies 50 (1/2): 21–36.

- Förster, Jürgen (2005). "The German Military's Image of Russia". Russia War, Peace and Diplomacy. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Fritz, Stephen: Ostkrieg: Hitler's War of Extermination in the East. 2015.

- Patricia Heberer and Jürgen Matthäus, ed (2008). Atrocities on Trial: Historical Perspectives on the Politics of Prosecuting War Crimes. Washington, D.C.: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1084-4. http://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/product/Atrocities-on-Trial,673325.aspx.

- Hannes Heer, ed (2004). War Of Extermination: The German Military In World War II. Berghahn Books. ISBN 1-57181-232-6.

- Ingrao, Christian (2013). Believe and Destroy: Intellectuals in the SS War Machine. Malden, MA: Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-6026-4.

- Jones, Bill Treharne (producer); Christopher Andrew (presenter and co-producer) (1989). The Fatal Attraction of Adolf Hitler (television documentary). BBC.

{{cite AV media}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Kay, Alex J. (2011) [2006]. Exploitation, Resettlement, Mass Murder: Political and Economic Planning for German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1940–1941. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781845451868. https://books.google.com/books?id=l20PlJtfk0IC.

- Kellerhoff, Sven Felix (2016). "NS-Verbrechensbefehle: "Es handelt sich um einen Vernichtungskampf"". https://www.welt.de/geschichte/zweiter-weltkrieg/article155923495/Es-handelt-sich-um-einen-Vernichtungskampf.html.

- Kühne, Thomas (April 2015). "Review: Marching into Darkness: The Wehrmacht and the Holocaust in Belarus, Waitman Wade Beorn". American Historical Review (Johns Hopkins University Press) 120 (2): 743–744. doi:10.1093/ahr/120.2.743.

- Large, David C. (1987). "Reckoning without the Past: The HIAG of the Waffen-SS and the Politics of Rehabilitation in the Bonn Republic, 1950–1961". The Journal of Modern History (University of Chicago Press) 59 (1): 79–113. doi:10.1086/243161.

- Lawson, Thomas (2006). The Church of England and the Holocaust: Christianity, Memory and Nazism. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell and Brewer. ISBN 978-1843832195.

- Müller, Rolf-Dieter; Ueberschär, Gerd (1997). Hitler's War in the East 1941–1945: A Critical Assessment. New York: Berghan Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-501-9.

- Neitzel, Sönke; Welzer, Harald (2012). Soldaten: On Fighting, Killing and Dying. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84983-949-5.

- Nelson, Andrew J. (3 August 2014). "Book review: 'Marching Into Darkness,' a UNO professor's book about Germany and World War II". Omaha World-Herald. http://www.omaha.com/living/book-review-marching-into-darkness-a-uno-professor-s-book/article_6d9530e5-573c-51d7-adfc-96db808887ce.html.

- Rutherford, Jeff: Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front: The German Infantry’s War, 1941–1944. 2014.

- Shepherd, Ben (June 2009). "The Clean Wehrmacht, the War of Extermination, and Beyond". War in History 52 (2): 455–473. doi:10.1017/S0018246X09007547. http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=5570268.

- Shepherd, Ben (2016). Hitler's soldiers: the German army in the Third Reich. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-17903-3.

- Shepherd, Ben (21 August 2015). "Review: Marching Into Darkness: The Wehrmacht and the Holocaust in Belarus, by Waitman Wade Beorn". The English Historical Review 130 (545). doi:10.1093/ehr/cev177. https://academic.oup.com/ehr/article-abstract/130/545/1046/534353/Marching-Into-Darkness-The-Wehrmacht-and-the. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Smelser, Ronald; Davies, Edward J. (2008). The Myth of the Eastern Front: The Nazi-Soviet War in American Popular Culture. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83365-3.

- Tauber, Kurt (1967). Beyond Eagle and Swastika: German Nationalism Since 1945. Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press.

- Wienand, Christiane (2015). Returning Memories: Former Prisoners of War in Divided and Reunited Germany. Rochester, N.Y: Camden House. ISBN 978-1571139047. https://books.google.com.au/books?id=BFWECgAAQBAJ&pg=PA39&lpg=PA39&dq=Soldaten+wie+alle+anderen+auch+waffen-ss&source=bl&ots=4-sRFkpV2j&sig=VadXiWYJNq0y1f2K7mc-nV1heng&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwicx5Sf-M3dAhXYF4gKHQ6IANEQ6AEwDXoECAMQAQ#v=onepage&q=Soldaten%20wie%20alle%20anderen%20auch%20waffen-ss&f=false. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Wette, Wolfram (2007). The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674025776.

- Wette, Wolfram (2009). "Mehr als dreitausend Exekutionen. Sachbuch: Die lange umstrittene Geschichte des "Kommissarbefehls" von 1941 in der deutschen Wehrmacht" (in German). http://www.badische-zeitung.de/literatur-1/mehr-als-dreitausend-exekutionen--16216637.html.

In German

- Detlev Bald, Johannes Klotz, Wolfram Wette: Mythos Wehrmacht. Nachkriegsdebatten und Traditionspflege. Aufbau, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-7466-8072-7.

- Michael Bertram: Das Bild der NS-Herrschaft in den Memoiren führender Generäle des Dritten Reiches, Ibidem-Verlag 2009, ISBN 978-3-8382-0034-7.

- Rolf Düsterberg: Soldat und Kriegserlebnis. Deutsche militärische Erinnerungsliteratur (1945—1961) zum Zweiten Weltkrieg. Motive, Begriffe, Wertungen., Niemeyer 2000, ISBN 978-3-484-35078-6.

- Jürgen Förster: Die Wehrmacht im NS-Staat. Eine strukturgeschichtliche Analyse. Oldenbourg, München 2007, ISBN 3-486-58098-1.

- Lars-Broder Keil, Sven Felix Kellerhoff: Ritterlich gekämpft? Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941–1945. In: Deutsche Legenden. Vom „Dolchstoß“ und anderen Mythen der Geschichte. Links, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-86153-257-3, S. 93–117.

- Wilfried Loth, Bernd-A. Rusinek: Verwandlungspolitik: NS-Eliten in der westdeutschen Nachkriegsgesellschaft. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 1998, ISBN 3-593-35994-4.

- Walter Manoschek, Alexander Pollak, Ruth Wodak, Hannes Heer (Hrsg.): Wie Geschichte gemacht wird. Zur Konstruktion von Erinnerungen an Wehrmacht und Zweiten Weltkrieg. Czernin, Wien 2003, ISBN 3-7076-0161-7.

- Walter Manoschek: Die Wehrmacht im Rassenkrieg. Der Vernichtungskrieg hinter der Front. Picus, Wien 1996, ISBN 3-85452-295-9.

- Manfred Messerschmidt: Die Wehrmacht im NS-Staat. Zeit der Indoktrination. von Decker, Hamburg 1969, ISBN 3-7685-2268-7.

- Rolf-Dieter Müller, Hans-Erich Volkmann (Hrsg.): Die Wehrmacht. Mythos und Realität. Hrsg. im Auftrag des Militärgeschichtlichen Forschungsamtes. Oldenbourg, München 1999, ISBN 3-486-56383-1.

- Klaus Naumann: Die „saubere“ Wehrmacht. Gesellschaftsgeschichte einer Legende. In: Mittelweg 36 7, 1998, Heft 4, S. 8–18.

- Sönke Neitzel, Harald Welzer: Soldaten: Protokolle vom Kämpfen, Töten und Sterben Fischer (S.), Frankfurt 2011, ISBN 978-3-10-089434-2

- Kurt Pätzold: Ihr waret die besten Soldaten. Ursprung und Geschichte einer Legende, Militzke 2000, ISBN 978-3-86189-191-8

- Alexander Pollak: Die Wehrmachtslegende in Österreich. Das Bild der Wehrmacht im Spiegel der österreichischen Presse nach 1945. Böhlau, Wien 2002, ISBN 3-205-77021-8.

- Rössler, Mechtild; Schleiermacher, Sabine (1996) (in German). Der "Generalplan Ost." Hauptlinien der nationalsozialistischen Planungs- und Vernichtungspolitik. Akademie-Verlag.

- Alfred Streim: Saubere Wehrmacht? Die Verfolgung von Kriegs- und NS-Verbrechen in der Bundesrepublik und der DDR. In: Hannes Heer (Hrsg.): Vernichtungskrieg. Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941–1944. Hamburg 1995, ISBN 3-930908-04-2, S. 569–600.

- Peter Steinkamp, Bernd Boll, Ralph-Bodo Klimmeck: Saubere Wehrmacht: Das Ende einer Legende? Freiburger Erfahrungen mit der Ausstellung. Vernichtungskrieg: Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941 bis 1944. In: Geschichtswerkstatt 29, 1997, S. 92–105.

- Michael Tymkiw: Debunking the myth of the saubere Wehrmacht. In: Word & Image 23, 2007, Heft 4, S. 485–492.

- Wolfram Wette: Die Wehrmacht. Feindbilder, Vernichtungskrieg, Legenden. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-7632-5267-3.

External links

- Video interview with Jeff Rutherford, the author of Combat and Genocide on the Eastern Front: The German Infantry’s War, 1941–1944, via the official website of C-SPAN

- Uncovered files shed light on Hitler's Wehrmacht, article via Deutsche Welle