Unsolved:Durin-gut

| Durin-gut | |

Picture of a Durin-gut in 1971 | |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | 두린굿 |

| Revised Romanization | Durin-gut |

| McCune–Reischauer | Turin-gut |

| Other name | |

| Hangul | 미친굿 |

| Revised Romanization | Michin-gut |

| McCune–Reischauer | Mich'in-gut |

| Other name | |

| Hangul | 추는굿 |

| Revised Romanization | Chuneun-gut |

| McCune–Reischauer | Ch'unŭn-gut |

The Durin-gut (lit. deranged ritual), also called the Michin-gut (lit. insane ritual) and the Chuneun-gut (lit. dancing ritual), is the healing ceremony for mental illnesses in the Korean shamanism of southern Jeju Island. While commonly held as late as the 1980s, it has now become very rare due to the introduction of modern psychiatry.

In Korean shamanism, a disease—whether physical or mental—is often thought to be caused by the entry of a malevolent spirit into the body. The Durin-gut seeks to cure the mental illness by exorcising this spirit, which is often identified as a yeonggam, a type of dokkaebi or goblin-like being with a penchant for attaching to human women that he lusts for. A similar exorcistic ceremony to treat mental illnesses, called the Gwang'in-gut (lit. Madman's ritual), is known in North Gyeongsang Province in mainland Korea.

The Durin-gut begins with the introductory ceremonies common to all major Jeju rituals, in which the gods are invited to the ritual ground. Once these have been completed, a number of dance sessions begin, in which the lead shaman sings and the apprentice shamans beat drums and gongs while the patient is made to dance to the music. The dancing may extend for as many as fifteen days. When the patient is physically unable to dance further after a number of sessions, the lead shaman talks to the patient, who is thought to be channeling the spirit inside their body. The shaman makes the patient recall the traumatic experience that caused the spirit's entry, and the spirit vows to leave the body. The ritual may be concluded by a number of preventive healing ceremonies, or only by a few rituals intended to avoid the spirit's vengeance and send back the gods.

Etymology

Durin-gut is a compound of durin, the adnominal form of the Jeju-language adjectival verb durida "to be deranged; to be foolish; to be lacking; to be young",[1][2] and the noun gut "ritual". It is also called the Michin-gut, meaning "insane ritual",[2] and the Chuneun-gut, literally "dancing ritual," after its key component of making the patient dance to the point of collapse.[1][lower-alpha 1]

Shamanic view of disease

Korean shamanism traditionally offers a number of supernatural explanations for human illnesses, both physical and mental. This includes the escape of part of the soul due to a traumatic or shocking event, especially common in childhood when the soul's association with the body is weaker; the attachment of a malignant force, such as a minor spirit or ritual impurity, upon the patient's body, also often caused by a traumatic event; and the anger of a god or an ancestor at the patient's behavior.[4][5]

Various ritual methods are used to cure disease. If part of a child's soul has escaped, the shaman holds rituals to put it back inside the body.[6] When a malevolent force has attached to the patient, small-scale healing ceremonies may be held to detach it.[7] Sometimes, the shaman confines the patient and makes them follow certain taboos in order to be cured.[8] Large-scale rituals, or gut, are required for certain diseases such as smallpox. In these rituals, the shaman engages in active communication with the gods or ancestors that have brought on the disease and convinces or intimidates them into departing or taking mercy.[8][9]

The Durin-gut—the healing ceremony for mental disorders in Jeju Island shamanism—belongs to the final category, in which the shaman communicates with a malevolent deity that has entered the body and forces it to depart.[6][7] The deity in question is often a yeonggam, a type of dokkaebi or goblin-like being. According to these spirits' origin myth, the Yeonggam bon-puri shamanic narrative, the yeonggam are seven brothers born in Seoul but exiled to Mount Halla in Jeju Island. The youngest of the yeonggam brothers is a hideous creature who often attaches to human women that are the objects of his lust, and drives them insane.[10] The other yeonggam brothers are more benevolent figures who the shaman convinces through ritual to take away their troublesome youngest sibling.[11] Other spirits are also thought to cause mental illnesses.[3] The purpose of the Durin-gut is to cure the illness by creating a gawp, or separation, between the human patient and these possessing spirits.[12]

Many, but not all, Korean healing ceremonies are in decline due to the introduction of modern medicine.[13] This includes the Durin-gut, which is very rarely performed as of 2006, although it was common as late as the 1980s.[3] A video of a 1984 Durin-gut ceremony—held for a twenty-one-year-old woman who had gone insane while working at a Seoul factory in order to financially support her family[14]—is the key primary source for ritual procedures.[15]

Ritual procedure

Preliminary rites

As with most Jeju rituals, the Durin-gut begins with the Samseok-ullim (lit. resounding of the three seats), a sacred drum performance held before the formal beginning of the ritual. This serves to forewarn the gods that the ritual will be held on that day.[16]

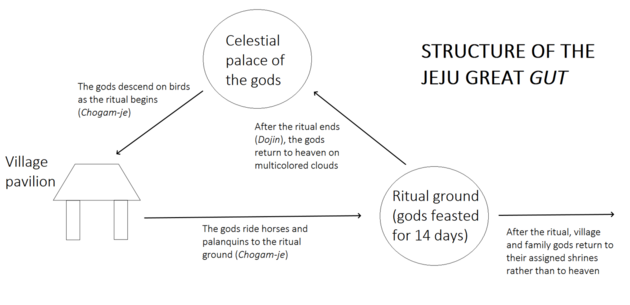

Again like all major rituals, the Durin-gut proper begins with a version of the Chogam-je, a series of ceremonies that serve to invite the gods into the ritual grounds.[17] The Chogam-je of the Durin-gut involves the Bepo-doeop-chim, in which the shaman narrates the Jeju creation myth;[18] the Nal-gwa-guk-seomgim (lit. serving up the day and country), in which the time and place of the ritual is specified for the sake of the gods;[19] the Yeonyu-dakkeum (lit. polishing the causes), in which the shaman explains the reasons the ritual is being held, in this case the specific details of the patient's illness;[2] the Gunmun-yeollim (lit. opening the divine gates), in which the shaman opens the gates of the gods' abode to allow them to descend into the human world;[20] the Sincheong-gwe, in which the shaman leads the gods from the village pavilion where they have descended into the actual ritual ground;[21] and the San-bada-bonbu-saroem (lit. Receiving omens to convey the message), in which the shaman divines the will of the gods by throwing his sacred mengdu implements and receives divine approval that the ritual should continue.[22][23]

The Chogam-je is followed by the Chumul-gong'yeon, when the shaman asks the gods to accept the offered sacrifices.[24]

Dances and exorcism

Once the preliminary rites have been completed, the essential procedure of the Durin-gut ensues: the Chum-chwium (lit. Making one dance).[1][lower-alpha 2] The Chum-chwium consists of a number of dancing sessions. A session begins with the shaman offering incense and new water and liquor at the altars for the assembled gods. Then the lead shaman sings while the apprentice shamans play the sacred drums to a relatively slow beat.[23] The lyrics of the song include fixed refrains as well as the Yeonggam bon-puri narrative,[25] but the shaman also improvises specific lyrics about the patient's life and condition. In the 1984 ritual, this included a comparison between the patient's life as an impoverished factory worker and the lives of the more fortunate. The patient and the villagers assembled to watch the ritual all wept as they heard the song, and the shaman herself wept while singing.[26]

Money, money, unspeakable money—to get this demon-like money

A forlorn child lost her parents early; thinking she should make good money

She went to that factory at Majang-dong, Seoul, Gyeonggi Province

Living in dormitories, eating regulated meals, sleeping regulated sleep...

Who is that person whose fortune is good, who lives at home with both his parents?

He goes to high school and to college; he wins success in society...[27]

The patient is made to dance to the song and the beat.[23] Once the song is finished, the apprentice shamans change to a much quicker drumbeat, to which the patient must now dance frantically. The instruments themselves also change; while the song is accompanied by the buk and janggu drums, the faster beat involves the buk drum and both suspended and bowl gongs.[23] Once the fast dance is finished, the shaman may sing and the patient may dance again to the slower beat.[28] Eventually, the patient rests for a while before the next session can begin. In the meantime, the shamans use bamboo leaves to spray liquor outside the gate as a sacrifice to minor gods who could not consume the offerings at the altars.[23]

The duration of sessions is variable. In the 1984 ritual, the shortest session of continuous dancing was ten minutes, while the longest was seventy minutes. The shortest duration of the resting period was ten minutes, while the longest was seventy-eight minutes[29] due to the patient falling into a deep sleep.[30] The number of sessions, and thus the overall length of the ritual, is also highly variable. The patient may refuse to go to the ritual ground at all, and the ritual must be cancelled before any dancing has been done. There are times when the illness is deemed to be cured after only a single session. In other cases, the patient is made to dance for as many as fifteen days.[31] The 1984 ritual involved twenty-three sessions of 823 minutes of dancing in total, extended over two afternoons, a full third day, and an hour in the morning of the fourth day. By late in the third day, the patient appeared to be dancing in a trance state.[32]

Patients are often reluctant or unwilling to dance, and must be persuaded or sometimes even forced to dance by the shaman and their family. The lead shaman and the family themselves will dance along to encourage the patient.[33] The patient of the 1984 ritual was not only reluctant, but also collapsed physically from fatigue while dancing a number of times. A rope was even suspended in the ritual ground so that she could lean on it.[29] The Durin-gut is also deeply exhausting for the shamans themselves, who must constantly keep up the song and drumbeat. Multiple shamans will occasionally take turns.[2]

Once the patient is physically incapable of dancing further, the lead shaman talks to the patient, who is thought to be channeling the spirit within their body. The shaman identifies the sort of spirit that has caused the illness and continues the conversation, hitting the patient with a peach branch if the spirit's answer is not satisfactory.[2][34] Sometimes, the shaman will even twist the patient's legs or nose.[2] Over the course of the conversation, the patient confesses traumatic memories that they had repressed or were unwilling to face; this trauma is considered the moment when the malevolent spirit entered the body. Shamanism scholar Kang Jeong-sik suggests that the shaman acts as a sort of psychotherapist.[35] In the case of the 1984 ritual, the patient talked about having discovered a corpse in the factory toilets and encountering her dead father in her dreams.[34] Ultimately, the shaman forces the spirit to vow that it will depart from the body at a certain date and time. The shaman then makes the patient swear that they will live a healthy life once the spirit has left.[36] This procedure is called the daegim-badeum (lit. Receiving vows).[37]

Concluding rites

The conclusion of the Durin-gut varies. In some cases, the shaman holds a rite called the Oksal-jium, asking forgiveness from the spirit for forcing it to leave and promising offerings in return for not harming the shaman or the patient. The patient channels the spirit's voice and tells the shaman the sorts of sacrifices it demands, which are given. The final ritual is Dojin, in which the gods invited in the Chogam-je are sent back to their abode[2][38] and beans are poured on the ritual ground.[39]

Alternatively, many other healing ceremonies may follow the Daegim-badeum. This was the case in the 1984 ritual,[40] when the shaman subsequently held the Neok-deurim, a ritual in which the shaman puts back parts of the soul that have left the body; then the Pudasi, a healing ceremony in which the shaman sings while stabbing at the patient with sacred knives; and finally the Aek-magi, in which the shaman makes an animal sacrifice to beseech the gods to ward off misfortune.[41] In such longer versions of the Durin-gut, the purpose of the Neok-deurim is to recall any parts of the human soul that have been displaced by the illness-causing spirit, while the Pudasi and the Aek-magi are preventive measures seeking to stop similar diseases from happening again.[40] The shaman of the 1984 Durin-gut then held the Gongsi-puri, a ritual dedicated to the gods of his mengdu implements that are the source of his shamanic power, before concluding with the Dojin.[39]

Sometimes for female patients,[42] the Dojin is followed by a final ceremony dedicated to the yeonggam called the Bel-gosa (lit. separate rite)[39] or Jangjeo-maji.[43] In this ceremony, the villagers all move to a seaside shrine, and lay out offerings of pork. The lead shaman then holds another Chogam-je, calling forth the yeonggam brothers.[44] A theatrical ritual called the Yeonggam-nori (lit. yeonggam play) then ensues,[43] with other shamans playing the roles of older yeonggam. The latter demand where their youngest brother is, and the lead shaman responds that he is having sex with the patient. The older yeonggam—speaking through the shamans' voices—declare that they have come to take back their brother, and the patient and the yeonggam exchange cups of liquor. While pouring liquor for the gods, the patient beseech them for an end to all her illnesses. The patient and the gods then dance together for a while. Another Pudasi is then held for the patient, who then eats the pork on the altars.[45] The shamans then load a boat with offerings and send it out to sea, symbolically sending the yeonggam out of Jeju Island.[43] A final Pudasi is held, in which the shaman uses knives to tear all of the patient's clothes. After changing clothes, the patient stays at a relative's house for some time, as dangerous spirits may be waiting for her at home. With this, the Durin-gut ends for good.[46]

Rituals such as the Neok-deurim, the Pudasi, and the Yeonggam-nori are all also held as independent healing rituals, so that this extended form of the Durin-gut represents an amalgamation of all major Jeju healing ceremonies.[40]

Mainland analogues

The principles of the Durin-gut are similar to those of the Gwang'in-gut (lit. Madman's ritual) of North Gyeongsang shamanism.[47] In the Gwang'in-gut, the shaman intimidates the spirit that is causing the mental illness by walking on the edge of a blade and brandishing swords, knives, and axes.[48] They then destroy a humanoid figurine representing the spirit while alternately speaking in both the voice of the chasa, the god that defeats the malevolent spirit, and the voice of the spirit being exorcised. Eventually, the spirit expresses—via the shaman's voice—its willingness to leave the patient's body.[49] The shaman then smears red ink (a surrogate for blood) on the patient's face, covers their head with a straw mat, and beats them with a peach branch to force the spirit out. Once the ritual has been completed, all implements are burnt.[50] Sometimes, cold water is splashed on the patient's face, and salt and grain are poured on the ritual ground once the exorcism is over.[51]

Notes

- ↑ In 2006, Kang Jeong-sik stated that the Durin-gut and the Chuneun-gut are similar but distinct rituals, with the former being addressed to dokkaebi and the latter to other miscellaneous spirits.[3] By 2015, Kang had revised her position and stated that they refer to the same ritual.[1]

- ↑ Ko Kwang-min refers to the dancing sessions as Chuneun-gut, and reserves the term Chum-chwium to the specific hectic dances at the end of the shaman's song in each session.[23]

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Kang J. 2015, p. 323.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 강정식 (Kang Jeong-sik). "Durin-gut". National Folk Museum of Korea. https://folkency.nfm.go.kr/kr/topic/detail/2025.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 219.

- ↑ Yi Y. 2018, pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 21, 228.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 21.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Yi Y. 2018, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Yun D. 2018, p. 149.

- ↑ Yi Y. 2018, pp. 183, 188–189.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 22, 219.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 225.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 23.

- ↑ Yi Y. 2018, pp. 184, 195–196.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 220.

- ↑ Kang J. 2015, p. 61.

- ↑ Kang J. 2015, pp. 46, 323.

- ↑ Kang J. 2015, pp. 63, 323.

- ↑ Kang J. 2015, pp. 64, 323.

- ↑ Kang J. 2015, pp. 67–69, 323.

- ↑ Kang J. 2015, pp. 76–79, 323.

- ↑ Kang J. 2015, p. 81.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 29.

- ↑ Kang J. 2015, pp. 99, 323.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 29, 31–34.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 29–31.

- ↑ "돈이돈아 말모른돈아 악마ᄀᆞ뜬 이금전ᄃᆞᆯ랑 설운애기 부모일찍조실ᄒᆞ난 좋은금전 벌젠해연 저경기도 서울지멘 마장동지멘 저공장가근 기숙사에서 생활ᄒᆞ고 시간밥먹고 시간ᄌᆞᆷ자고... 어떤사름 팔ᄌᆞ가좋아 양친부모에 고향집사는고 고등ᄒᆞᆨ교 대ᄒᆞᆨ나왕 사회에서 출세ᄒᆞ고..." Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 30

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 25.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 25–27.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 129.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 25–27, 34.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 221.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 36.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 228–229.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 36, 222.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 34.

- ↑ Kang J. 2015, p. 324.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 38.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 223.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 36–38.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 226.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 222.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, p. 39.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Ko K. & Kang J. 2006, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Yun D. 2018, p. 168.

- ↑ Yun D. 2018, p. 164.

- ↑ Yun D. 2018, p. 165.

- ↑ Yun D. 2018, p. 166.

- ↑ Yun D. 2018, p. 160.

Works cited

- 강정식 (Kang Jeong-sik) (2015). Jeju Gut Ihae-ui Giljabi. Jeju-hak Chongseo. Minsogwon. ISBN 9788928508150. http://www.kyobobook.co.kr/product/detailViewKor.laf?ejkGb=KOR&barcode=9788928508150. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- 고광민 (Ko Kwang-min); 강정식 (Kang Jeong-sik) (2006). National Research Institute of Cultural Heritage. ed. Jeju-do Chuneun-gut. Pia. ISBN 89-86148-28-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=PkAzAQAAIAAJ. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- 윤동환 (Yun Dong-Hwan) (2018). "Donghaean musok-eseo Gwang'in-gut-ui wisang". Han'guk Minsokhak 67: 147–170. ISSN 1229-6953. http://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE07462494. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- 이용범 (Yi Yong-buhm) (2018). "Musok chibyeong uirye-ui yuhyeong-gwa chibyeong weolli". Bigyo Minsokhak 67: 177–199. ISSN 1598-1010. http://www.dbpia.co.kr/journal/articleDetail?nodeId=NODE0874346. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

|