Philosophy:Chaos magic

| Part of a series on |

| Chaos magic |

|---|

|

| Key Concepts |

|

|

| Notable Figures |

| Organisations |

Template:Magic sidebar Chaos magic, also spelled chaos magick,[1][2] is a modern tradition of magic.[3] Emerging in England in the 1970s as part of the wider neo-pagan and esoteric subculture,[4] it drew heavily from the occult beliefs of artist Austin Osman Spare, expressed several decades earlier.[3] It has been characterised as an invented religion,[5] with some commentators drawing similarities between the movement and Discordianism.[6] Magical organizations within this tradition include the Illuminates of Thanateros and Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth.

The founding figures of chaos magic believed that other occult traditions had become too religious in character.[7] They attempted to strip away the symbolic, ritualistic, theological, or otherwise ornamental aspects of these occult traditions, to leave behind a set of basic techniques that they believed to be the basis of magic.[8]

Chaos magic teaches that the essence of magic is that perceptions are conditioned by beliefs, and that the world as it is normally perceived can be changed by deliberately changing those beliefs.[9] Chaos magicians subsequently treat belief as a tool, often creating their own idiosyncratic magical systems and blending such different things as "practical magic, quantum physics, chaos theory, and anarchism."[10]

Scholar Hugh Urban has described chaos magic as a union of traditional occult techniques and applied postmodernism[11] – particularly a postmodernist skepticism concerning the existence or knowability of objective truth,[12] positing that chaos magic rejects the existence of absolute truth, and views all occult systems as arbitrary symbol-systems that are only effective because of the belief of the practitioner.[12]

History

Origins and influences (1900–1982)

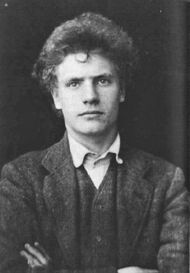

Austin Osman Spare's work in the early to mid 1900s is largely the source of chaos magical theory and practice.[13] Specifically, Spare developed the use of sigils and the use of gnosis to empower them.[14][15] Although Spare died before chaos magic emerged, he has been described as the "grandfather of chaos magic".[16] Working during much the same period as Spare, Aleister Crowley's publications also provided a marginal yet early and ongoing influence, particularly for his syncretic approach to magic and his emphasis on experimentation and deconditioning.[17] Later, concurrent with the growth of religions such as Wicca in the 1950s and 1960s, different forms of magic became more common, some of which came in "explicitly disorganized, radically individualized, and often quite 'chaotic' forms".[18] In the 1960s and the decade that followed, Discordianism, the punk movement, postmodernism and the writings of Robert Anton Wilson emerged, and they were to become significant influences on the form that chaos magic would take.[19][20]

During the mid-1970s chaos magic appeared as "one of the first postmodern manifestations of occultism",[14] built on the rejection of a need to adhere to a "single, systematized convention",[21] and aimed at distilling magical practices down to a result-oriented approach rather than following specific practices based on tradition.[22] An oft quoted line from Peter Carroll is "Magic will not free itself from occultism until we have strangled the last astrologer with the guts of the last spiritual master."[23]

Peter J. Carroll and Ray Sherwin are considered to be the founders of chaos magic,[10] although Phil Hine points out that there were others "lurking in the background, such as the Stoke Newington Sorcerors".[24] Carroll was a regular contributor to The New Equinox, a magazine edited by Sherwin, and thus the two became acquainted.[24][25]

In 1976-77 the first chaos magic organization Illuminates of Thanateros (IOT) was announced.[26] The following year, 1978, was a seminal year in the origin of chaos magic, seeing the publication of both Liber Null by Carroll and The Book of Results by Sherwin – the first published books on chaos magic.[27][28]

According to Carroll, "When stripped of local symbolism and terminology, all systems show a remarkable uniformity of method. This is because all systems ultimately derive from the tradition of Shamanism. It is toward an elucidation of this tradition that the following chapters are devoted."[29]

Development and spread (1982–1994)

New chaos magic groups emerged in the early 1980s – at first, located in Yorkshire, where both Sherwin and Carroll were living. The early scene was focused on a shop in Leeds called The Sorceror's Apprentice, owned by Chris Bray. Bray also published a magazine called The Lamp of Thoth, which published articles on chaos magic, and his Sorceror's Apprentice Press re-released both Liber Null and The Book of Results, as well as issuing Psychonaut and The Theatre of Magic.[30] The "short-lived" Circle of Chaos, which included Dave Lee, was formed in 1982.[31] The rituals of this group were published by Paula Pagani as The Cardinal Rites of Chaos in 1985.[32]

Ralph Tegtmeier (Frater U∴D∴), who ran a bookshop in Germany and was already practicing his own brand of "ice magick", translated Liber Null into German.[31] Tegtmeier was inducted into the IOT in the mid-1980s, and later established the German section of the order.[31]

As chaos magic spread, people from outside Carroll and Sherwin's circle began publishing on the topic. Phil Hine, along with Julian Wilde and Joel Biroco, published a number of books on the subject that were particularly influential in spreading chaos magic techniques via the internet.[33]

In 1981, Genesis P-Orridge established Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth (TOPY).[34] P-Orridge had studied magic under William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin in the 1970s, and was also influenced by Aleister Crowley and Austin Osman Spare, as well as the psychedelic movement.[35][33] TOPY practiced chaos magic alongside their other activities, and helped raise awareness of chaos magic in subcultures like the Acid house and Industrial music scenes.[36] Along with being an influence on P-Orridge, Burroughs was himself inducted into the IOT in the early 1990s.[37]

Pop culture: (1994–2000s)

From the beginning, chaos magic has had a tendency to draw on the symbolism of pop culture in addition to that of traditional magical systems; the rationale being that all symbol systems are equally arbitrary, and thus equally valid – the belief invested in them being the thing that matters.[38] The symbol of chaos, for example, was lifted from the fantasy novels of Michael Moorcock.[39]

Preluded by Kenneth Grant – who had studied with both Crowley and Spare, and who had introduced elements of H.P. Lovecraft's fictional Cthulhu mythos into his own magical writings[40] – there was a trend for chaos magicians to perform rituals invoking or otherwise dealing with entities from Lovecraft's work, such as the Great Old Ones. Hine, for example, published The Pseudonomicon (1994), a book of Lovecraftian rites.[14]

From 1994 to 2000, Grant Morrison wrote The Invisibles for DC Comics' Vertigo imprint, which has been described by Morrison as a "hypersigil": "a dynamic miniature model of the magician's universe, a hologram, microcosm or 'voodoo doll' which can be manipulated in real time to produce changes in the macrocosmic environment of 'real' life."[41] Both The Invisibles and the activities of Morrison themself were responsible for bringing chaos magic to a much wider audience in the late 1990s and early 2000s, with the writer outlining their views on chaos magic in the "Pop Magic!" chapter of A Book of Lies (2003)[38] and a Disinfo Convention talk.[42]

Morrison's particular take on chaos magic exemplified the irreverent, pop cultural elements of the tradition, with Morrison arguing that the deities of different religions (Hermes, Mercury, Thoth, Ganesh, etc.) are nothing more than different cultural "glosses" for more universal "big ideas"[41] – and are therefore interchangeable: both with each other, and with other pop culture icons like The Flash, Metron, and Madonna.[41]

Post-chaos magic: 2010s

Alan Chapman – whilst praising chaos magic for "breathing new life" into Western occultism, thereby saving it from "being lost behind a wall of overly complex symbolism and antiquated morality" – has also criticised chaos magic for its lack of "initiatory knowledge": i.e., "teachings that cannot be learned from books, but must be transmitted orally, or demonstrated", present in all traditional schools of magic.[43] Innovations continue into the 2020s, as found in social media, fandoms, and webcomics.[44]

Beliefs, core concepts, and practices

Belief as a tool

The central defining tenet of chaos magic is arguably the idea that belief is a tool for achieving effects.[45] In chaos magic, complex symbol systems like Qabalah, the Enochian system, astrology or the I Ching are treated as maps or "symbolic and linguistic constructs" that can be manipulated to achieve certain ends but that have no absolute or objective truth value in themselves. Religious scholar Hugh Urban notes that chaos magic's "rejection of all fixed models of reality" reflects one of its central tenets: "nothing is true everything is permitted".[12]

Both Urban and religious scholar Bernd-Christian Otto trace this position to the influence of postmodernism on contemporary occultism.[12][46] Another influence comes from Spare, who believed that belief itself was a form of psychic energy that became locked up in rigid belief structures, and that could be released by breaking down those structures. This "free belief" could then be directed towards new aims. Otto has argued that chaos magic "filed away the whole issue of truth, thus liberating and instrumentalising individual belief as a mere tool of ritual practice."[47]

Magical paradigm shifting

Peter J. Carroll suggested assigning different worldviews to the sides of a dice, and then inhabiting the associated particular random paradigm for a set length of time when its number is rolled. For example, 1 might be paganism, 2 might be monotheism, 3 might be atheism, and so on.[12]

Phil Hine has stated that the primary task here is "to thoroughly decondition" the aspiring magician from "the mesh of beliefs, attitudes and fictions about self, society, and the world" that his or her ego associates with:

Our ego is a fiction of stable self-hood which maintains itself by perpetuating the distinctions of "what I am/what I am not, what I like/what I don't like", beliefs about ones politics, religion, gender preference, degree of free will, race, subculture etc all help maintain a stable sense of self.[48]

Cut-up technique

The cut-up technique is an aleatory literary technique in which a written text is cut up and rearranged, often at random, to create a new text. The technique can also be applied to other media such as film, photography, and audio recordings. It was pioneered by Brion Gysin and William S. Burroughs.[49]

Burroughs – who practiced chaos magic, and was inducted into the Illuminates of Thanateros in the early 1990s – was adamant that the technique had a magical function, stating, "the cut-ups are not for artistic purposes".[50] Burroughs used his cut-ups for "political warfare, scientific research, personal therapy, magical divination, and conjuration"[50] – the essential idea being that the cut-ups allowed the user to "break down the barriers that surround consciousness".[51] Burroughs stated:

I would say that my most interesting experience with the earlier techniques was the realization that when you make cut-ups you do not get simply random juxtapositions of words, that they do mean something, and often that these meanings refer to some future event. I've made many cut-ups and then later recognized that the cut-up referred to something that I read later in a newspaper or a book, or something that happened... Perhaps events are pre-written and pre-recorded and when you cut word lines the future leaks out.[51]

David Bowie compared the randomness of the cut-up technique to the randomness inherent in traditional divinatory systems, like the I Ching or tarot.[52]

Genesis P-Orridge, who studied under Burroughs[53] described it as a way to "identify and short-circuit control, life being a stream of cut-ups on every level. They are a means to describe and reveal reality and the multi-faceted individual in which/from which reality is generated."[54]

References

Citations

- ↑ Carroll (2008).

- ↑ Humphries & Vayne (2005), p. 17.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Chryssides (2012), p. 78.

- ↑ Woodman (2003), p. 2.

- ↑ Cusack & Sutcliffe (2017), p. [page needed].

- ↑ Urban (2006), pp. 233–238; Duggan (2014), p. 96.

- ↑ Drury (2011), p. 86.

- ↑ Drury (2011), p. 86; Hine (2009), p. 15.

- ↑ Woodman (2003), p. 15-16, 165, 201.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Meletiadis (2023), p. 2.

- ↑ Clarke (2004), pp. 105–106.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Urban (2006), pp. 240–243.

- ↑ Carroll (1987), p. 8; Siepmann (2018), p. 85.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Siepmann (2018), p. 85.

- ↑ Urban (2006), p. 231.

- ↑ Vitimus (2009), p. 115.

- ↑ Hine (2009), p. 45.

- ↑ Urban (2006), p. 233.

- ↑ Hine (2009), p. 10.

- ↑ Siepmann (2018), p. 84.

- ↑ Siepmann (2018), p. 86.

- ↑ Otto (2020), pp. 767–768.

- ↑ Carroll (2008), p. 46.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Hine (2009), p. 8.

- ↑ Duggan (2014), p. 96.

- ↑ Otto (2020), pp. 762–763.

- ↑ Duggan (2014), p. 91.

- ↑ Meletiadis (2023), pp. 8–23.

- ↑ Carroll (1987), p. 30.

- ↑ Hine (2009), p. 9.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Otto (2020), p. 775.

- ↑ Hine (2009), p. 11.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Duggan (2014), p. 95.

- ↑ Baddeley (2010), p. 156.

- ↑ Siepmann (2018), p. 90.

- ↑ Siepmann (2021), p. 283.

- ↑ Stevens (2014), ch. 22.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Morrison (2003), p. 16-25.

- ↑ Nozedar (2008), p. 49.

- ↑ Levenda (2013), p. 8.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Morrison (2003), p. 21.

- ↑ Metzger (2002), pp. 98–115.

- ↑ Chapman (2008), p. 12.

- ↑ Evans 2024, p. 45.

- ↑ Otto 2020, p. 769f.

- ↑ Otto 2020, p. 764.

- ↑ Otto 2020, p. 771.

- ↑ Hine (2009), p. [page needed].

- ↑ Cran (2016), p. 86.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Harris (2017), p. 134.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Burroughs (1974), p. 28.

- ↑ Doggett (2011), p. 201.

- ↑ P-Orridge (2003), p. 112.

- ↑ P-Orridge (2010), p. 132.

Works cited

- Baddeley, Gavin (2010). Lucifer Rising: Sin, Devil Worship & Rock n' Roll (third ed.). London: Plexus. ISBN 978-0-85965-455-5.

- Burroughs, William S. (1974). The Job: Interviews with William S. Burroughs. Random House. ISBN 9780802100573.

- Carroll, Peter J. (1987). Liber Null & Psychonaut. Weiser Books. ISBN 9781609255299.

- Carroll, Peter J. (2008). Psybermagick: Advanced Ideas in Chaos Magick: Revised Edition. Original Falcon Press. ISBN 9781935150657.

- Chapman, Alan (2008). Advanced Magick for Beginners. Karnac Books. ISBN 9781904658412.

- Chryssides, George D. (2012). Historical Dictionary of New Religious Movements (2 ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-6194-7.

- Clarke, Peter (2004). Encyclopedia of New Religious Movements. Routledge. ISBN 9781134499700.

- Cran, Rona (2016). Collage in Twentieth-Century Art, Literature, and Culture: Joseph Cornell, William Burroughs, Frank O'Hara, and Bob Dylan. Routledge. ISBN 9781317164296.

- The Problem of Invented Religions. Taylor & Francis. 2017. ISBN 9781317373353.

- Doggett, Peter (2011). The Man who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. Random House. ISBN 9781847921451.

- Drury, Nevill (2011). The Watkins Dictionary of Magic: Over 3000 Entries on the World of Magical Formulas, Secret Symbols and the Occult. Duncan Baird Publishers. ISBN 9781780283623.

- Duggan, Colin (2014). "Perennialism and Iconoclasm: Chaos Magick and the Legitimacy of Innovation". in Asprem, Egil. Contemporary Esotericism. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Evans, Kenneth D. (2024). Authority, information organization, and posthumanism in the rhetoric of chaos magic (PhD thesis). Texas Woman's University.

{{cite thesis}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Harris, Oliver (2017). "William S. Burroughs: Beating Postmodernism". in Belletto, Steven. The Cambridge Companion to the Beats. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107184459.

- Hine, Phil (2009). Condensed Chaos: An Introduction to Chaos Magic. Original Falcon Press. ISBN 9781935150664.

- Humphries, G.; Vayne, J. (2005). Now That's What I Call Chaos Magick. United Kingdom: Mandrake of Oxford. ISBN 978-1869928742.

- Levenda, Peter (2013). The Dark Lord: H.P. Lovecraft, Kenneth Grant and the Typhonian Tradition in Magic. Nicolas-Hays, Inc.. ISBN 9780892542079.

- Meletiadis, Vasileios M. (2023). ""Book Zero" through the Years: The First Two Editions of Peter Carroll’s Liber Null". Aries: Journal for the Study of Western Esotericism: 1–31. doi:10.1163/15700593-tat00004. https://brill.com/view/journals/arie/aop/article-10.1163-15700593-tat00004/article-10.1163-15700593-tat00004.xml?Tab%20Menu=abstract.

- Metzger, Richard (2002). Disinformation: The Interviews: Uncut & Uncensored. Red Wheel Weiser. ISBN 9781609259365.

- Morrison, Grant (2003). "Pop Magic!". in Metzger, Richard. Book of Lies: The Disinformation Guide to Magick and the Occult. Red Wheel Weiser. ISBN 9780971394278.

- Nozedar, Adele (2008). The Element Encyclopedia of Secret Signs and Symbols: The Ultimate A-Z Guide from Alchemy to the Zodiac. HarperCollins UK. ISBN 9780007264452.

- Otto, Bernd-Christian (2020). "The Illuminates of Thanateros and the institutionalisation of religious individualisation". Religious Individualisation. pp. 759–796. doi:10.1515/9783110580853-038. ISBN 9783110580853.

- P-Orridge, Genesis Breyer (2010). Thee Psychick Bibile: Thee Apocryphal Scriptures ov Genesis Breyer P-Orridge and Thee Third Mind ov Thee Temple ov Psychick Youth. Feral House. ISBN 9781932595949.

- P-Orridge, Genesis Breyer (2003). "Magick Squares: The Magical Processes and Methods of William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin". in Metzger, Richard. Book of Lies: The Disinformation Guide to Magick and the Occult. Red Wheel Weiser. ISBN 9780971394278.

- Siepmann, Daniel (2018). "Unholy Progeny: Psychic TV and Witch House at the Crossroads of Occultism in the Information Age". Journal of Musicological Research 37 (1): 81–104. doi:10.1080/01411896.2018.1413870.

- Siepmann, Daniel (2021). "Occultism in the Acid House Music of Psychic TV". Preternature 10 (2): 249–292.

- Stevens, Matthew Levi (2014). The Magical Universe of William S. Burroughs. Mandrake.

- Urban, Hugh (2006). Magia Sexualis: Sex, Magic, and Liberation in Modern Western Esotericism. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520932883.

- Vitimus, Andrieh (2009). Hands-on Chaos Magic: Reality Manipulation Through the Ovayki Current. Llewellyn Worldwide. ISBN 978-0-7387-1508-7.

- Woodman, Justin (2003). Modernity, Selfhood, and the Demonic: Anthropological Perspectives on "Chaos Magick" in the United Kingdom (Ph.D. dissertation). Goldsmiths, University of London. doi:10.25602/gold.00028683.

Further reading

- Atanes, Carlos (2022). Chaos Magic for Skeptics. Mandrake of Oxford. ISBN 9781914153174.

- Blackwell, Christopher (2010). "Before, Chaos, and After". http://wiccanrede.org/2010/12/interview-with-phil-hine/.

- Carr-Gomm, Philip; Heygate, Richard (2010). The Book of English Magic. The Overlook Press. ISBN 9781590207604.

- Carroll, Peter J. (1992). Liber Kaos. Weiser Books. ISBN 9780877287421.

- Carroll, Peter J. (2010). Octavo: A Sorcerer-Scientist's Grimoire (Roundworld ed.). Mandrake of Oxford. ISBN 9781906958176.

- Clutterbuck, Brenton (7 April 2017). "Chaos in the UK: From the KLF to Reclaim the Streets". http://historiadiscordia.com/chaos-in-the-uk-from-the-klf-to-reclaim-the-streets/.

- Gyrus (1997). "Chaos and Beyond". https://dreamflesh.com/interview/phil-hine/.

- Hawkins, Jaq D. (1996). Understanding Chaos Magic. Capall Bann Publishing. ISBN 1-898307-93-8.

- Hawkins, Jaq D. (2017). Chaonomicon. Chaos Monkey Press.

- Hine, Phil (1998). Prime Chaos: Adventures in Chaos Magic. New Falcon Publications. ISBN 9781609255299.

- Hine, Phil (2009). The Pseudonomicon. New Falcon Publications. ISBN 9781935150640.

- Sherwin, Ray (1992). The Book of Results. Revelations 23 Press. ISBN 9781874171003.

|