Unsolved:Faun

The faun (Latin: Faunus, pronounced [ˈfäu̯nʊs̠]; Ancient Greek:, pronounced [pʰâu̯nos]) is a half-human and half-goat mythological creature appearing in Greek and Roman mythology.

Originally fauns of Roman mythology were ghosts (genii) of rustic places, lesser versions of their chief, the god Faunus. Before their conflation with Greek satyrs, they and Faunus were represented as naked men (e.g. the Barberini Faun). Later fauns became copies of the satyrs of Greek mythology, who themselves were originally shown as part-horse rather than part-goat.

By the Renaissance, fauns were depicted as two-footed creatures with the horns, legs, and tail of a goat and the head, torso, and arms of a human; they are often depicted with pointed ears. These late-form mythological creatures borrowed their look from the satyrs, who in turn borrowed their look from the god Pan of the Greek pantheon. They were symbols of peace and fertility, and their Greek chieftain, Silenus, was a minor deity of Greek mythology.[1]

Origins

Romans believed fauns stirred fear in men traveling in lonely, faraway or wild places. They were also capable of guiding men in need, as in the fable of The Satyr and the Traveller, in the title of which Latin authors substituted the word Faunus. Fauns and satyrs were originally quite different creatures: Whereas late-period fauns are half-man and half-goat, satyrs originally were depicted as stocky, hairy, ugly dwarves or woodwoses, with the ears and tails of horses. Satyrs also were more woman-loving than fauns, and fauns were rather foolish where satyrs tended to be sly.

Ancient Roman mythological belief included a god named Faunus often associated with bewitched woods, and conflated with the Greek god Pan[2][3] and a goddess named Fauna who were goat people.

In art

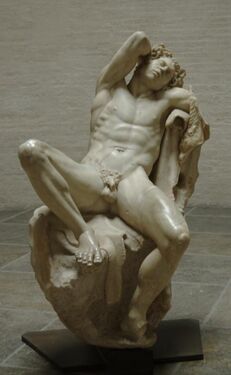

The Barberini Faun (located in the Glyptothek in Munich, Germany ) is a Hellenistic marble statue from about 200 BCE, found in the Mausoleum of the Emperor Hadrian (the Castel Sant'Angelo) and installed at Palazzo Barberini by Cardinal Maffeo Barberini (later Pope Urban VIII). Gian Lorenzo Bernini restored and refinished the statue.[4]

The House of the Faun in Pompei, dating from the 2nd century BCE, was so named because of the dancing faun statue that was the centerpiece of the large garden. The original now resides in the National Museum in Naples and a copy stands in its place.[5]

The French symbolist Stéphane Mallarmé's well-known masterpiece L'après-midi d'un faune (published in 1876) describes the sensual experiences of a faun who has just woken up from his afternoon sleep and discusses his encounters with several nymphs during the morning in a dreamlike monologue.[6] The composer Claude Debussy based his symphonic poem Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune (1894) [7] on the poem, which also served as the scenario for a ballet entitled L'après-midi d'un faune (or Afternoon of a Faun) choreographed to Debussy's score in 1912 by Vaslav Nijinsky.

Statue of a faun; Vatican, Brooklyn Museum Archives, Goodyear Archival Collection

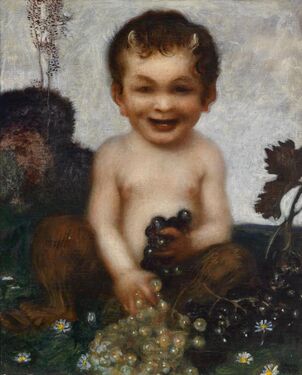

Maenad and Fauns, 1902–1912, by Isobel Lilian Gloag.

In fiction

- Nathaniel Hawthorne's (1860) romance The Marble Faun is set in Italy, and was said to have been inspired by his viewing the Faun of Praxiteles in the Capitoline Museum.[8]

- In H.G. Wells' (1895) The Time Machine, in the year 802,701 CE, while exploring the far future, the Time Traveller sees "a statue – a faun, or some such figure, minus the head."[9]

- Mr. Tumnus, in C. S. Lewis's The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe (1949), is a faun. Lewis said that the famous The Chronicles of Narnia story all came to him from a single picture he had in his head of a faun carrying an umbrella and parcels through a snowy wood. In the film series, fauns are distinct from satyrs, which are more goat-like in form.

- In Lolita, the protagonist is attracted to pubescent girls whom he dubs "nymphets"; "faunlets" are the male equivalent.

- In the 1981 film My Dinner with Andre, it is related how fauns befriend and take a mathematician to meet Pan.

- In Guillermo del Toro's 2006 film El Laberinto del Fauno (Pan's Labyrinth), a faun guides the film's protagonist, Ofelia, to a series of tasks, which lead her to a wondrous netherworld.

- In Rick Riordan's The Son of Neptune (2011), the character Don is a faun. In the book, several fauns appear, begging for money. Due to his memory of the Greek satyrs, Percy Jackson feels like there should be more to fauns. Also, in the prequel to The Son of Neptune, The Lost Hero, Jason Grace calls Gleeson Hedge a faun upon learning that he is a satyr. In the third instalment in the series, The Mark of Athena, Frank Zhang calls Hedge a faun.[citation needed]

- In The Goddess Within, a visionary fiction novel written by Iva Kenaz, the main heroine falls in love with a faun.

- In the Spyro video game series, Elora is a faun from Avalar, who helps Spyro the dragon navigate the world around him.

- In Carnival Row, fauns or 'pucks' are one of the mythical creatures that are part of the series.

See also

- Baphomet

- Centaur

- Cernunnos

- Faunus

- Glaistig

- Goatman (urban legend)

- Khnum

- Kinnara

- Krampus

- Minotaur

- Pan (god)

- Puck (mythology)

- Satyr

- Se'irim

- Silvanus (mythology)

- Yaksha

References

- ↑ Canadian Oxford Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. p. 541.

- ↑ "Phaunos". http://www.theoi.com/Georgikos/Phaunos.html.

- ↑ "faun (mythical character)". Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/faun. Retrieved 2017-09-04.

- ↑ Barberini Faun. Introduction to Greece lecture 34 (image). University of Texas. Archived from the original on 2012-10-20. Retrieved 2014-06-23.

- ↑ Dancing faun statuette. Edgar L. Owen, Ltd. (gallery) (image). Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- ↑ Mallarmé, S. (n.d.). L'après-midi d'un faune. http://www.angelfire.com/art/doit/mallarme.html. Retrieved 2022-10-22.

- ↑ composer Claude Debussy, Leopold Stokowski conducting the London Symphony Orchestra (16 May 2009). Debussy – Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun (orchestral audio recording illustrated with images of classical paintings) – via YouTube.

- ↑ "Online discussion of The Marble Faun (1860) and its connection with the statue". California Polytechnical University. http://cla.calpoly.edu/~jbattenb/marblefaun/marblefaun/criticism.htm.

- ↑ Wells, H.G. (1961). The Time Machine (reprint ed.). New York, NY: Dolphin Books. p. 246.

|