Unsolved:Self-praise of Shulgi (Shulgi D)

(Shulgi D)

Self-praise of Shulgi (Shulgi D) is a Sumerian myth, written on clay tablets dated to between 2100 and 2000 BC.

Compilation

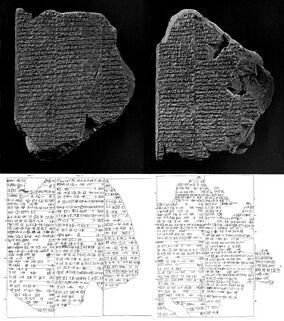

The myth was discovered on the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, catalogue of the Babylonian section (CBS), tablet number 11065 from their excavations at the temple library at Nippur. This was translated by George Aaron Barton in 1918 and first published as "Sumerian religious texts" in "Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions", number three, entitled "Hymn to Dungi" (Dungi was later renamed to Shulgi).[1] The tablet is 7 inches (18 cm) by 5.4 inches (14 cm) by 1.6 inches (4.1 cm) at its thickest point.[2] Barton noted that similar hymns were published by Stephen Herbert Langdon and introduced into Sumerian religion at the time of the Third dynasty of Ur onwards. He dates the tablet to the reign of Shulgi, saying "The script of our tablets shows that this copy was made during the time of the First Dynasty of Babylon, but that does not preclude an earlier date for the composition of the original."[2] Further tablets were used by Jacob Klein to expand and translate the myth again in 1981. He used several other tablets from the University Museum in Pennsylvania including CBS 8289. He also included translations from tablets in the Nippur collection of the Museum of the Ancient Orient in Istanbul, catalogue number 4571. He also used tabled 5379 from the Louvre in Paris.[3]

Story

In the story, Shulgi is praised and compared to all manner of animals and wondrous things such as a tree.

| “ | "You are as strong as an ildag tree planted by the side of a watercourse. You are a sweet sight, like a fertile mec tree laden with colourful fruit. You are cherished by Ninegala, like a date palm of holy Dilmun. You have a pleasant shade, like a sappy cedar growing amid the cypresses."[4] | ” |

His interactions and relationships with a large number of the pantheon of Sumerian gods are described along with victories in foreign lands and description of the royal barge.

| “ | "Imbued with terrible splendour on the Exalted River, it was adorned with holy horns, and its golden ram symbol gleamed in the open air. Its bitumen was the ... bitumen of Enki provided generously by the abzu; its cabin was a palace. It was decorated with stars like the sky. Its holy ..."[4] | ” |

Discussion

Samuel Noah Kramer suggests that Shulgi hymns speaking about the achievements of the king focussed on the two areas of social behaviour and religion. He is both shown to be concerned for social justice, law and equity along with being faithful in his priestly rites and interaction with the gods. He notes "uppermost in their minds was the Ekur, the holy temple of Nippur where virtually every king in the hymnal repertoire brought gifts, offerings, and sacrifices to Enlil."[5]

See also

- Barton Cylinder

- Royal Correspondence of Ur

- Debate between Winter and Summer

- Debate between sheep and grain

- Enlil and Ninlil

- Old Babylonian oracle

- Hymn to Enlil

- Kesh temple hymn

- Lament for Ur

- Sumerian religion

- Sumerian literature

References

- ↑ Barton, George A. (George Aaron) (1918). Miscellaneous Babylonian inscriptions. New Haven, Yale Univ. Press. p. 26. https://archive.org/details/miscellaneousbab00bartuoft/page/26/mode/2up.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 George Aaron Barton (1918). Miscellaneous Babylonian inscriptions. Yale University Press. p. 52. https://books.google.com/books?id=nn5hAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- ↑ Klein, Jacob, Three Shulgi Hymns. Sumerian Royal Hymns Glorifying King Shulgi of Ur. Bar Ilan University Press: Ramat-Gan, 1981: 50-123

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 ETCSL Self-praise of Shulgi (Shulgi D) - Translation

- ↑ Samuel Noah Kramer (1 November 1988). In the World of Sumer: An Autobiography. Wayne State University Press. pp. 116–. ISBN 978-0-8143-2121-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=KliA7MjJEDQC&pg=PA116. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

External links

- CDLI University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA. Museum no.: CBS 11065

- Barton, George Aaron., Miscellaneous Babylonian Inscriptions, Yale University Press, 1918. Online Version

- ETCSL Self-praise of Shulgi (Shulgi D) - Bibliography

- ETCSL Self-praise of Shulgi (Shulgi D) - Translation

- ETCSL Self-praise of Shulgi (Shulgi D) - Composite Text