Unsolved:Völva

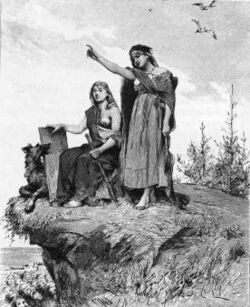

A vǫlva or völva (Old Norse and Icelandic, respectively; plural forms vǫlur and völvur, sometimes anglicized vala; also spákona or spækona) is a female shaman and seer in Norse religion and a recurring motif in Norse mythology.

Names and etymology

The vǫlur were referred to by many names. Old Norse vǫlva means "wand carrier" or "carrier of a magic staff",[1] and it continues Proto-Germanic *walwōn, which is derived from a word for "wand" (Old Norse vǫlr).[2] Vala, on the other hand, is a literary form based on vǫlva.[2]

Another name for the vǫlva is fjǫlkunnig (plenty of knowing) indicating she knew seiðr, spá and galdr. A practitioner of seiðr is known as a seiðkona "seiðr-woman" or a seiðmaðr "seiðr-man".

A spákona or spækona "spá-woman"[3] (with an Old English cognate, spæwīfe)[4] is a specialised vǫlva; a "seer, one who sees", from the Old Norse word spá or spæ referring to prophesying and which is cognate with the present English word "spy", continuing Proto-Germanic *spah- and the Proto-Indo-European root *(s)peḱ (to see, to observe) and consequently related to Latin speciō ("I see") and Sanskrit spaśyati and paśyati (पश्यति, "to see").[5]

Overview

Vǫlur practiced seiðr, spá and galdr, practices which encompassed shamanism, sorcery, prophecy and other forms of indigenous magic associated with women. Seiðr in particular had connotations of ergi (unmanliness), a serious offense in Norse society.

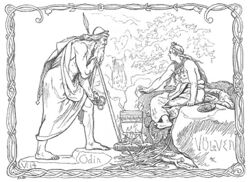

Historical and mythological depictions of vǫlur show that they were held in high esteem and believed to possess such powers that even the father of the gods, Odin himself, consulted a vǫlva to learn what the future had in store for the gods. Such an account is preserved in the Völuspá, which roughly translates to "Prophecy of the Vǫlva". In addition to the unnamed seeress (possibly identical with Heiðr) in the Vǫluspá, other examples of vǫlur in Norse literature include Gróa in Svipdagsmál, Þórbjǫrgr in the Saga of Erik the Red and Huld in Ynglinga saga.

The vǫlur were not considered to be harmless.[6] The goddess who was most skilled in magic was Freyja, and she was not only a goddess of love, but also a warlike divinity who caused screams of anguish, blood and death, and what Freyja performed in Asgard, the world of the gods, the vǫlur tried to perform in Midgard, the world of men.[6] The weapon of the vǫlva was not the spear, the axe or the sword, but instead they were held to influence battles with different means, and one of them was the wand,[6] (see the section wands and weaving, below).

Early accounts

Template:Battle red Cimbri and Teutons defeats.

Template:Battle blue Cimbri and Teutons victories.

The earliest descriptions of Germanic prophetesses appear in Roman accounts about the Cimbri, whose priestesses were aged women dressed in white. They sacrificed the prisoners of war and sprinkled their blood in order to prophesy coming events.[7]

In his Commentarii de Bello Gallico (1, 50) Julius Caesar writes in the course of clashes with Germanic tribesmen under Ariovistus (58 BCE):

When Caesar inquired of his prisoners, wherefore Ariovistus did not come to an engagement, he discovered this to be the reason – that among the Germans it was the custom for their matrons to pronounce from lots and divination whether it were expedient that the battle should be engaged in or not; that they had said, "that it was not the will of heaven that the Germans should conquer, if they engaged in battle before the new moon.

Tacitus also writes about prophetesses among the Germanic peoples in his Histories 4, 61 - notably a certain Veleda: "by ancient usage the Germans attributed to many of their women prophetic powers and, as the superstition grew in strength, even actual divinity."

Jordanes relates in his Getica (XXIV:121) of Gothic haliurunnas, witches who were driven into exile by King Filimer when the Goths had settled in Oium (Ukraine ). The name is possibly a corruption of a Gothic Halju-runnos, meaning "hell-runners" or "runners to the realm of the dead".[8] These witches were condemned to seek refuge far away and, according to this account, engendered the Huns.

The Lombard historian Paul the Deacon, who died in Southern Italy in the 790s, wrote on how his people once had departed from southern Scandinavia.[9] He tells of a conflict between the early Lombards and the Vandals. The latter turned to one Godan (presumably Odin), while Gambara, the mother of the two Lombard chieftains Ibor and Aio, turned to Godan's spouse Frea (presumably Freyja/Frigg). Frea helped Gambara play a trick on Odin and thanks to the Gambara's good relations with the goddess, her people won the battle.[10]

A detailed eyewitness account of a human sacrifice by what may have been a vǫlva was given by Ahmad ibn Fadlan as part of his account of a diplomatic mission to Volga Bulgaria in 921. In his description of the funeral of a Scandinavian chieftain, a slave girl volunteers to die with her master. After ten days of festivities, she is stabbed to death by an old woman (a sort of priestess who is referred to as "Angel of Death") and burnt together with the deceased in his boat (see Oseberg Ship).

Viking society

In Norse society, a vǫlva was an elderly woman who had released herself from the strong family bonds that normally surrounded women in Norse clans. She travelled the land, usually followed by a retinue of young people, and she was summoned in times of crisis. She had immense authority and she charged well for her services.[11]

In addition, many aristocratic Viking women wanted to serve Freyja and represent her in Midgard. They married Viking warlords who had Odin as a role model, and they settled in great halls that were earthly representations of Valhalla.[9] In these halls there were magnificent feasts with ritualized meals, and the visiting chieftains can be likened with the einherjar, the fallen warriors who fought bravely and were served drinks by Valkyries. However, the duties of the mistresses were not limited to serving mead to visiting guests, but they were also expected to take part in warfare by manipulating weaving tools magically when their spouses were out in battle. Scholars no longer believe that these women waited passively at home, and there is evidence for their magic activities both in archaeological finds and in Old Norse sources, such as the Darraðarljóð.[9]

It is difficult to draw a line between the aristocratic lady and the wandering vǫlva, but Old Norse sources present the vǫlva as more professional and she went from estate to estate selling her spiritual services.[12] The vǫlva had greater authority than the aristocratic lady, but both were ultimately dependent on the benevolence of the warlord that they served.[inconsistent] When they had been attached to a warlord, their authority depended on their personal competence and credibility.[9]

Saga sources

In Flateyjarbók, toward the end of Norna-Gests þáttr, Norna-Gest states that "spákonur traveled around the country-side and fore-told the fates of men."[13]

In Landnámabók, a Volva named Þuríðr Sundafyllir gained the epithet of "filler of inlets" during a famine in Iceland, when she used her magic powers to fill the fjords with fish.

The Saga of Eric the Red relates that the settlers in Greenland c. 1000 were suffering a time of starvation. In order to prepare for the future, the vǫlva Þórbjǫrgr lítilvǫlva ("the little vǫlva") was summoned. Before her arrival the whole household was thoroughly cleaned and prepared. The high seat, which was otherwise reserved for the master and his wife, was furnished with down pillows.

The vǫlva appeared in the evening, dressed in a foot-length blue or black cloak decked with gems to the hem. In her hand she wielded a wand, the symbolic distaff (seiðstafr), which was adorned with brass and decked with gems on the knob. In the saga of Örvar-Oddr, the seiðkona also wears a blue or black cloak and carries a distaff (a wand which allegedly has the power of causing forgetfulness in one who is tapped three times on the cheek by it). The colour of the cloak may be less significant than the fact that it was intended to signify the otherness of the seiðkona.

The Saga of Eric the Red further relates that around her neck she wore a necklace of glass pearls, and on her head she wore a headpiece of black lamb trimmed with white cat skin. Around her waist she wore a belt of amadou from which hung a large pouch, where she hid the tools that she used during the seiðr. On her feet she wore shoes of calfskin and the shoelaces had brass knobs in the ends, and on her hands she wore gloves of cat skin, which were white and fluffy inside.

As the vǫlva entered the room, she was hailed with reverence by the household, and then she was led to the high seat, where she was provided with dishes prepared only for her. She had a porridge made of goat milk and a dish made of hearts from all the kinds of animals at the homestead. She ate the dishes with a brass spoon and a knife whose point was broken off.

The vǫlva was to sleep at the farm during the night and the next day was reserved for her dance. In order to dance the seiðr, she needed special tools. First, she positioned herself on a special elevated platform and a group of young women sat down around her. The girls sang special songs intended to summon the powers that the vǫlva wished to communicate with. The session was a success because the vǫlva was permitted to see far into the future and the famine was averted.

In the prologue of the Prose Edda, related by a vǫlva,[14] the origin of Thor's wife Sif is detailed, where she is said to be a spákona. Snorri contextually correlates Sif with the oracular seeress Sibyl on this basis.[15][16]

Archaeological record

Scandinavian archaeologists have discovered wands in about 40 female graves, and they have usually been discovered in rich graves with valuable grave offerings which shows that the vǫlvas belonged to the highest level of society.[17]

One example is a grave in Fyrkat, Denmark which turned out to be the richest grave in the area.[17] She had been buried in a wagon from which the wheels had been removed.[17] She had been plainly clad in what was probably only a long dress.[17] Around her toes, she had toe rings, which suggests that she was buried without shoes or only in sandals so that the rings showed.[17] At her head, she had a Gotlandic buckle which may have been used as a box, and she also owned objects from Finland and Russia.[17] At her feet, she had a box which contained her magic tools, comprising a pellet from an owl as well as small bones from birds and mammals, and in a pouch she had the seeds of Hyoscyamus niger ("henbane").[18] If such seeds are thrown into a fire, they produce a hallucinogenic smoke which causes a sense of flying.[18] In the grave there was also a small silver amulet that represented a chair made from a stump.[18] When such small silver chairs are discovered in graves, they always belong to a woman, and it is possible that they represented objects such as the platform where the vǫlva performed her rituals and Hlidskjalf from which Odin watched across the world.[18]

Another notable grave was the Oseberg Ship in Norway that revealed two women who had received a sumptuous burial.[18] One of the women was most likely a high-ranking lady who knew how to practice seiðr as she had been buried with a wand of wood.[18] In the grave, there were also four cannabis seeds, which probably had been in the pillows that supported the corpses.[18] Additional cannabis seeds were discovered in a small leather pouch.[18]

Around the ninth century, a vǫlva was buried with considerable splendour in Hagebyhöga in Östergötland, Sweden.[19] In addition to being buried with her wand, she had received great riches which included horses, a wagon and an Arabian bronze pitcher.[19] There was also a silver pendant which represents a woman with a broad necklace around her neck.[19] This kind of necklace was only worn by the most prominent women during the Iron Age and some have interpreted it as Freyja's necklace, Brísingamen. The pendant may represent Freyja herself, the most prominent vǫlva of them all.[19]

In Birka, a vǫlva and a warrior were once buried together. Above them, a spear was positioned in order to dedicate the dead couple to Odin.[20] They had probably served Freyja and Odin, two deities of war, and he had done so with his spear and she with her wand.[20]

Wands and weaving

In theory, invisible fetters and bonds could be controlled from a loom, and if a lady loosened a knot in the woof, she could liberate the leg of her hero.[21] But if she tied a knot, she could stop the enemy from moving.[21] The men may have fought on the battle field in sweat and blood, but in a spiritual way, their women took part.[21] It is not by coincidence that archaeologists find weaving tools and weapons side by side.[21]

A distaff possessed magical powers, and in the world of the gods, the Norns twined the threads of fate.[21] In Helgakviða Hundingsbana I, norns arrive at the birth of Helgi Hundingsbane and twined his fate as a hero, and it is possible that these Norns were not divine beings but vǫlur.[22] Many of the wands that have been excavated have a basket-like shape in the top, and they are very similar to distaffs used for spinning linen.[22] One theory for the origin of the word seiðr is "thread spun with a distaff", and according to this theory, practicing magic was to send out spiritual threads.[21] Since the Norsemen believed that the Norns controlled people's fate by spinning, it is very likely that they considered individual fates to be controllable with the same method.[22]

It is not a coincidence that women are called "peace-weavers" in Beowulf, and since Freyja had started the first war, it was on the part of the vǫlva to decide when to start wars by practicing magic.[9] This is probably why Harald Bluetooth, who was at war with the Holy Roman Emperor apparently kept a vǫlva at Fyrkat.[9]

The Wife's Lament could be a poem about a peace-weaver.

Sexual rites and drugs

Today, it is generally accepted among scholars that fertility was essential in Viking society, and the most famous find that testifies to such rites is a small phallic statuette that was found in Rällinge in Sweden in the early 20th century.[23] The appearance of this statuette indicates that it was related to fertility rites and it is usually interpreted as Freyja's brother Freyr.[23] Adam of Bremen tells of the phallic statue of Freyr in the Temple at Uppsala and of the ribald songs that were sung during the rituals.[23] In Völsa þáttr, there is an account on how a horse's penis was worshipped by a pagan family, an account that has connections with an old Indo-Aryan sacrificial rite.[24]

Some wands that have been excavated cannot be associated with distaffs, but instead appear to represent a phallus, and moreover the use of magic had close associations with sexuality in Old Norse society.[23] In the Lokasenna, due to his interest in seiðr, Loki is depicted accusing Odin of being ergi, which suggests that he could be perceived as unmanly, cowardly and accepting the 'female' role in sexual intercourse.[23] As early as 1902, an anonymous German scholar (he did not dare publish in his own name) wrote on how seiðr was connected with sex.[23] He argued that the wand was an obvious phallic symbol and why magic should otherwise be considered taboo for men.[23] It was possible that the magic practices included sexual rites.[23] As early as 1920, it was noted that the name of the male magic practitioner Ragnvald Rettilbein referred to such practices, as rettilbein means "straight member".[23]

The vǫlur were known for their art of seduction, which was one of the reasons why they were considered dangerous.[25] One of the stanzas in Hávamál warns against sexual intercourse with a woman who is skilled in magic, because the one who does so runs the risk of being caught in a magic bond and also risks getting ill.[25] Freyja, who is the mistress of seiðr, has a free sexual life that gives her a bad reputation in certain myths.[25]

One of the methods for seducing men may have been the use of drugs.[25] In Fyrkat, the grave of a vǫlva revealed the use of henbane, a drug which not only produces hallucinations but can also be a powerful aphrodisiac.[25] If Freyja was the goddess of love in Asgard, the vǫlva was her counterpart in Midgard.[25]

Other practices

The vǫlur could also employ drums during their sessions as in Sami shamanism.[26] All vǫlur were not surrounded by the same retinue and preparations as Þórbjǫrgr, but she could also perform the seiðr alone, which was called útiseta (literally, "sitting out").[27][28] This practice appears to have involved meditation or introspection, possibly for the purpose of divination. Blain (2001) sees it as an aspect of seiðr reminiscent of shamanism. The term is derived from a 13th-century Law of Iceland, which outlawed útiseta at vekja trǫll upp ok fremja heiðni "sitting out to wake up trolls and practicing heathenry". Although the theoretical legal punishment for this offense was death, nobody was convicted under it until a minor witch craze reached Iceland in the 17th century.[29] Keyser (1854) describes it as "a peculiar kind of sorcery [...] in which the magician sat out at night under the open sky [...] especially to inquire into the future".

Male practitioners

During the Christianization of Norway, King Olaf Trygvasson had seidmen tied up and thrown on a skerry at ebb. Men who practiced sorcery or magic were not received with the same respect but killed like animals and tortured to death because they were dealing with a practice that was held to be in the domain of women.[11][30] This offense was considered ergi, "unmanliness, sexually perverse". The Heimskringla relates that Ragnvaldr Rettilbein, one of Harald Fairhair's sons by the Sami woman Snæfrid was a seiðmaðr.[11][30] The king had him burnt to death inside a house with a large group of fellow male practitioners.[11]

In Lokasenna, Loki taunts Odin for having practiced magic on Samsø, something which was considered ergi.[30]

Disappearance

The disappearance of the vǫlur was due to the Roman Catholic Church, which along with civil governments had laws enacted against them, as in this Anglo-Saxon Canon law:

If any wicca (witch), wiglaer (wizard), false swearer, morthwyrtha (worshipper of the dead) or any foul contaminated, manifest horcwenan (whore), be anywhere in the land, man shall drive them out.

We teach that every priest shall extinguish heathendom and forbid wilweorthunga (fountain worship), licwiglunga (incantations of the dead), hwata (omens), galdra (magic), man worship and the abominations that men exercise in various sorts of witchcraft, and in frithspottum (peace-enclosures) with elms and other trees, and with stones, and with many phantoms.

– 16th canon law enacted under King Edgar in the 10th century

They were persecuted and killed in the course of Christianization, which also led to an extreme polarization of the role of females in Germanic society.[citation needed]

Resurgence of the traditions of the vǫlur are apparent in Europe and the United States within Heathen reconstructionism and the Christian community.[citation needed]

In fiction

The term Spaewife was used as the title for several fictional works: Robert Louis Stevenson's poem "The Spaewife"; John Galt's historical romance The Spaewife: A Tale of the Scottish Chronicles; and John Boyce's The Spaewife, or, The Queen's Secret (under the pen-name Paul Peppergrass).

Melville

Francis Melville describes a spae-wife as a type of elf in The Book of Faeries.

No taller than a human finger, fairy spae wives are usually dressed in the clothes of a peasant. However, when properly summoned, the attire changes from common to magnificent: blue cloak with a gem-lined collar and black lambskin hood lined with catskin, calfskin boots, and catskin gloves. Like human spae wives, they can also predict the future, through runes, tea leaves and signs generated by natural phenomena, and are good healers. They are said to be descended from the erectors of the standing stones.

See also

- European witchcraft

- Galdr

- Huld

- Nithe

- Seiðr

Notes

- ↑ Mercatante & Dow 2004, II:893.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Hellquist 1922:1081

- ↑ The Tale of Norna-Gest

- ↑ Hellquist 1922:851

- ↑ Hellquist 1922:851

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Harrison & Svensson 2007:55

- ↑ Strabo in Geographica 7.2.3

- ↑ Scardigli, Piergiuseppe, Die Goten: Sprache und Kultur (München 1973) pp. 70-71.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Harrison & Svensson 2007:69

- ↑ Harrison & Svensson 2007:74

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Steinsland, G. & Meulengracht Sørensen, P. 1998:81

- ↑ "Viking seeresses - National Museum of Denmark" (in en). National Museum of Denmark. http://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-viking-age/religion-magic-death-and-rituals/viking-seeresses/.

- ↑ The Tale of Norna-Gest

- ↑ Mercatante & Dow 2004, II:893

- ↑ The prologue of Heimskringla

- ↑ The prologue of Heimskringla in translation

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 Harrison & Svensson 2007:56

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Harrison & Svensson 2007:57

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Harrison & Svensson 2007:58

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Harrison & Svensson 2007:62

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 Harrison & Svensson 2007:72

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Harrison & Svensson 2007:73

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 23.6 23.7 23.8 Harrison & Svensson 2007:75

- ↑ Harrison & Svensson 2007:75-78

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Harrison & Svensson 2007:79

- ↑ Steinsland, G. & Meulengracht Sørensen, P. 1998:82

- ↑ Blain 2001:61ff

- ↑ Keyser 1854:275

- ↑ Blain 2001:62

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Harrison & Svensson 2007:65

References

- Blain, Jenny (2002). Nine Worlds of Seid-Magic: Ecstasy and Neo-Shamanism in North European Paganism. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-25650-X. https://books.google.com/books?id=n06nbwFmJHcC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_v2_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Harrison, D. & Svensson, K. (2007): Vikingaliv. Fälth & Hässler, Värnamo. Lua error: not enough memory.

- Hellquist, E. (1922): Svensk etymologisk ordbok. C. W. K. Gleerups förlag, Lund.

- Keyser, R. (1854): The Religion of the Northmen

- Mercatante, Anthony S. & Dow, James R. (2004): The Facts on File Encyclopedia of World Mythology and Legend, 2nd edition. Two volumes. Facts on File, Inc. Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

- Steinsland, G. & Meulengracht Sørensen, P. (1998): Människor och makter i vikingarnas värld. Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.

Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1. Lua error: Internal error: The interpreter exited with status 1.