Unsolved:Xiuhcoatl

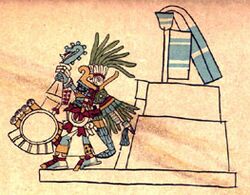

In Aztec religion, Xiuhcōātl [ʃiʍˈkoːaːt͡ɬ] was a mythological serpent, regarded as the spirit form of Xiuhtecuhtli, the Aztec fire deity sometimes represented as an atlatl or a weapon wielded by Huitzilopochtli. Xiuhcoatl is a Classical Nahuatl word that translates as "turquoise serpent" and also carries the symbolic and descriptive translation of "fire serpent".

Xiuhcoatl was a common subject of Aztec art, including illustrations in Aztec codices, and was used as a back ornament on representations of both Xiuhtecuhtli and Huitzilopochtli.[1] Xiuhcoatl is interpreted as the embodiment of the dry season and was the weapon of the sun.[2] Apparently, the royal diadem (or xiuhuitzolli, "pointed turquoise thing") of the Aztec emperors represented the tail of the Xiuhcoatl, the fire serpent.[3]

Attributes

Typically, Xiuhcoatl was depicted with a sharply back-turned snout and a segmented body. Its tail resembled the trapeze-and-ray year sign and probably does represent that symbol. In Nahuatl, the word xihuitl means "year", "turquoise", and "grass". Often, the tail of Xiuhcoatl is marked with the Aztec symbol for "grass". The body of the Xiuhcoatl was wrapped with knotted strips of paper, linking the serpent to bloodletting and sacrifice.[4]

In the Postclassic period, the Xiuhcoatl fire serpent was associated with the three concepts associated with its tail-sign: turquoise, grass, and the solar year. All three of these concepts were associated with fire in central Mexico during the Postclassic, with dry grass and the solar year being closely identified with fire and solar heat. Page 46 of the pre-Columbian Codex Borgia depicts four smoking Xiuhcoatl serpents arranged around a burning turquoise mirror. A turquoise-rimmed mirror has been found at the Maya city of Chichen Itza, with four fire serpents encircling the rim. The archaeological site of Tula has warrior columns on Mound B that bear mirrors on their backs, also surrounded by four Xiuhcoatl fire serpents.[4]

Although the Fire Serpent easily may be traced back to the Early Postclassic period in Tula, its ultimate origins are unclear. During the Classic Period, the War Serpent of Teotihuacan was probably a forerunner of Xiuhcoatl, it was also depicted with the grass symbol, flames, and the trapeze-and-ray year symbol.[4]

Mythology

Xiuhcoatl was considered to be the nahual, or spirit form, of the Aztec fire deity Xiuhtecuhtli.[5] It was a lightning-like weapon borne by Huitzilopochtli.[6] With it, soon after his birth, he pierced his sister Coyolxauhqui, destroying her, and also defeated the Centzon Huitznahua.[7] This incident is illustrated on a fragment of broken sculpture excavated from the Great Temple of Tenochtitlan. The fragment was originally a part of a large stone disk that depicted the fallen Coyolxauhqui with the Xiuhcoatl fire serpent penetrating her chest. This Xiuhcoatl wielded by Huitzilopochtli symbolizes the forces of darkness being driven out by the fiery rays of the sun.[4]

Tonatiuh, the sun god, was guided across the sky by Xiuhcoatl and was used by him as a weapon against his underworld enemies, the stars, and the moon.[8]

Ritual

During the Panquetzaliztli ceremony, Xiuhcoatl was represented by a paper serpent with red feathers emerging from its open maw to represent flames. During the ceremony, burning torches also symbolized Xiuhcoatl and a serpent dance was performed.[9]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Stone figure of Xiuhcoatl". https://www.google.com/culturalinstitute/asset-viewer/stone-figure-of-xiuhcoatl/8gGLbiPoLfaKjw.

- ↑ López Austin 2002, p.142.

- ↑ Olivier & López Luján, p.85.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Miller & Taube 1993, 2003, pp.188-189.

- ↑ Fernández 1992, 1996, pp.107, 160.

- ↑ Read & Gonzalez 2000, pp.194, 230.

- ↑ Read & Gonzalez 2000, pp.194, 230. Miller & Taube 1993, 2003, p.188.

- ↑ Matos Moctezuma & Solis Olguín 2002, p.414.

- ↑ Matos Moctezuma 1988, p.140.

References

- Durán, Diego (1994). The History of the Indies of New Spain. Civilization of the American Indian series, no. 210. Doris Heyden (trans., annot., and introd.) (translation of Historia de las Indias de Nueva-España y Islas de Tierra Firme, English ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2649-3. OCLC 29565779.

- Fernández, Adela (1996) (in es). Dioses Prehispánicos de México. Mexico City: Panorama Editorial. ISBN 968-38-0306-7. OCLC 59601185.

- López Austin, Alfredo (2002). "The Natural World". Aztecs. London: Royal Academy of Arts. ISBN 1-903973-22-8. OCLC 56096386.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo (1988). The Great Temple of the Aztecs: Treasures of Tenochtitlan. New Aspects of Antiquity series. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27752-4. OCLC 17968786.

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo; Felipe Solis Olguín (2002). Aztecs. London: Royal Academy of Arts. ISBN 1-903973-22-8. OCLC 56096386.

- Miller, Mary; Karl Taube (2003). An Illustrated Dictionary of the Gods and Symbols of Ancient Mexico and the Maya. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27928-4. OCLC 28801551. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780500279281.

- Olivier, Guilhem; López Luján; Leonardo (2009). "Images of Moctezuma and his symbols of power". Moctezuma: Aztec Ruler. London: The British Museum Press. pp. 78–123. ISBN 978-0-7141-2585-5. OCLC 416257004.

- Read, Kay Almere; Jason González (2000). Handbook of Mesoamerican Mythology. Oxford: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-340-0. OCLC 43879188.