Social:It (character)

| It | |

|---|---|

| Stephen King character | |

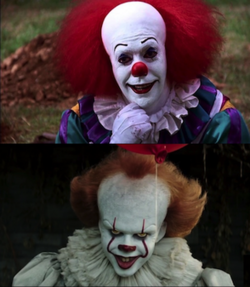

Top: Tim Curry as Pennywise in the 1990 miniseries Bottom: Bill Skarsgård as Pennywise in the 2017 film | |

| First appearance | It (1986) |

| Last appearance | It Chapter Two (2019) |

| Created by | Stephen King |

| Portrayed by | 1990 miniseries: Tim Curry (Pennywise) Florence Paterson (Mrs. Kersh) Frank C. Turner (Alvin Marsh) Steve Makaj (Captain Hanscom) Tony Dakota (Georgie Denbrough) 1998 television series: Lilliput (Vikram) Parzaan Dastur (Siddharth) 2017 film and 2019 sequel: Bill Skarsgård (Pennywise) Tatum Lee (Judith) Javier Botet (Hobo / Leper / The Witch) Carter Musselman (Headless Boy) Jackson Robert Scott (Georgie Denbrough) Stephen Bogaert (Alvin Marsh) Joan Gregson (Mrs. Kersh) Owen Teague (Patrick Hockstetter) |

| Information | |

| Alias |

|

It is the title character in Stephen King's 1986 horror novel It. The character is an ancient cosmic evil which preys upon the children of Derry, Maine, roughly every 27 years, using a variety of powers that include the ability to shapeshift, manipulate, and go unnoticed by adults. During the course of the story, It primarily appears in the form of Pennywise the Dancing Clown.

King stated in a 2013 interview that he came up with the idea for Pennywise after asking himself what scared children "more than anything else in the world", and feeling that the answer was clowns.[1] King thought of a troll like the one in the children's tale "Three Billy Goats Gruff",[2] who inhabited a sewer system.[2]

The character was portrayed in its Pennywise form by Tim Curry in the 1990 television adaptation,[3] in the 1998 television adaptation by Lilliput, and by Bill Skarsgård in the 2017 film adaptation and in It Chapter Two, which was released on September 6, 2019.[4]

Appearances

Literature

In the novel, It is a shapeshifting monster who usually takes the form of Pennywise the Dancing Clown, originating in a void containing and surrounding the Universe—a place referred to in the novel as the "Macroverse" (a concept similar to the later established "Todash Darkness" of the Dark Tower novels). It ended up on prehistoric Earth during an asteroid impact and made its home under the land that Derry would be built on, preying on indigenous tribes before confining its feedings within the town. It would sleep for approximately 27 to 30 years at a time, using its time awake to wreak chaos and feed on human fear by assuming what its prey fear the most. It has a preference for children since their fears are easier to interpret in a physical form, gradually breaking them akin to "salting the meat" before killing them. It can manipulate people with weaker wills, making them indifferent to the horrific events that unfold or serve as unknowing accomplices.

At several points in the novel, It claims its true name is Robert "Bob" Gray, and is named "It" by the Losers Club. Throughout the book, It is generally referred to as male due to usually appearing as Pennywise, but the Losers come to believe It may be female with the human mind safely comprehending It's true form to that of a monstrous giant spider. But It's true appearance is briefly observed by Bill Denbrough via the Ritual of Chüd as a mass of swirling destructive orange lights known as "deadlights", which inflict insanity or death on any living being that directly stares into them (a common Lovecraftian device). The only known person to survive the ordeal is Bill's wife Audra Phillips, although she is rendered catatonic by the experience.

It's natural enemy is the "Space Turtle" or "Maturin", another ancient dweller of King's "Macroverse" who, eons ago, created the known universe and possibly others by vomiting them out while it had a stomach ache. The Turtle shows up again in King's series The Dark Tower. Wizard and Glass, one of the novels in the series, suggests that It, along with the Turtle, are themselves creations of a separate, omnipotent creator referred to as "the Other" (possibly Gan, who is said to have created the various universes where King's novels take place). The Turtle and It are eternal enemies (creation versus consumption). It may, in fact, be either a "twinner" of or an actual one of the six greater demon elementals mentioned by Mia in The Dark Tower VI: Song of Susannah, as the Spider is not one of the Beam Guardians.

Throughout the novel It, some events are depicted from Pennywise's point of view, describing itself as the "superior" being with the Turtle as an equal and humans as mere "toys". It's hibernation begins and ends with horrific events of sorts, like the mysterious disappearance of the Derry Township's 300 settlers in 1740-43 or the ironworks explosion. It awoke during a great storm that flooded part of the city in 1957, with Bill's brother Georgie the first in a line of killings before the Losers Club fight the monster, a confrontation culminating in Bill using the Ritual of Chüd to severely wound It and force It into hibernation. Continually surprised by the Losers' victory, It briefly questions its superiority before claiming that they were only lucky, as the Turtle is working through them as the group and could easily picked them off individually. It is finally destroyed 27 years later in the second Ritual of Chüd, and an enormous storm damages the downtown part of Derry to symbolize It's death.

There's a tangential appearance of Pennywise in King's 2011 novel 11/22/63, where time-traveling Jake meets a couple of the children from It and asks them about a recent murder in their town. Apparently, the murderer "wasn't the clown." It also appears to the protagonist, Jake Epping, in the old ironworks where it taunts Jake about "the rabbit-hole," referring to the time portal.

Film and television

In the 1990 miniseries, Pennywise is portrayed by English actor Tim Curry. One original guise is made for the miniseries: Ben Hanscom (played by Steve Makaj).

In the 2017 film adaptation and its 2019 sequel It Chapter Two, Pennywise is portrayed by Swedish actor Bill Skarsgård.[5] The second movie slightly deviates from the book in It's final form being a drider-version of Pennywise and is motivated by revenge on the Losers Club. Will Poulter was originally cast as Pennywise, with Curry describing the role as a "wonderful part" and wishing Poulter the best of luck, but dropped out of the production due to scheduling conflicts and first film's original director Cary Fukunaga leaving the project. Spanish actor Javier Botet was cast as the Hobo leper in both movies and the monstrous form of Ms. Kersh in the second film. Two original guises were made for the first film: the Headless Boy, a burnt victim of the Kitchener Ironworks incident (played by Carter Musselman), and the Amedeo Modigliani–based painting Judith (played by Tatum Lee).[6]

Pennywise is loosely adapted in the 1998 Indian television series Woh as a specter who was originally an outcast named Vikram, portrayed by actor Lilliput with Parzaan Dastur portraying his younger self.

Reception and legacy

Several media outlets such as The Guardian have spoken of the character, ranking it as one of the scariest clowns in film or pop culture.[7][8][9] The Atlantic said of the character; "the scariest thing about Pennywise, though, is how he preys on children's deepest fears, manifesting the monsters they're most petrified by (something J. K. Rowling would later emulate with boggarts)."[10] British scholar Mikita Brottman has also said of the miniseries version of Pennywise; "one of the most frightening of evil clowns to appear on the small screen" and that it "reflects every social and familial horror known to contemporary America".[11] Author Darren Shan cited Pennywise as an inspiration behind the character Mr. Dowling in his 12.5 book serial Zom-B.[12] Critics such as Mark Dery have drawn connections between the character of Pennywise and serial killer John Wayne Gacy,[13][14][15] who would dress up at community children's parties as "Pogo the Clown";[15][14] Dery has stated that the character "[embodied] our primal fears in a sociopathic Ronald McDonald who oozes honeyed guile".[16] King however makes no mention of Gacy in discussing his inspiration for It.[2]

The American punk rock band Pennywise took its name from the character.[17]

Association with 2016 clown sightings

—Writer Stephen King's reaction to the recurring clown scare phenomenon.[18]

The character has also been cited as a possible inspiration for two separate incidents of people dressing up as creepy clowns in Northampton, England and Staten Island, New York.[1][19] In 2016, several reports of random appearances by "evil clowns" were reported by the media, including seven people in Alabama charged with "clown-related activity".[20][21] Several newspaper reports cited the character of Pennywise as an influence for the outbreak, which led to King commenting that people should lower hysteria caused by the sightings and not take his work seriously.[22] The first reported sighting of people dressed as evil clowns was in Greenville, South Carolina, where a small boy spoke to his mother of a pair of clowns that had attempted to lure him away.[23][24] After such an incident, a number of clowns have since been spotted in various American states including Florida, New York, Wisconsin and Kentucky, and subsequently in other Western countries, from August 2016.[25][26][27][28][29] By October 2016, in the wake of hundreds of "clown sightings" across the United States and Canada, the phenomenon had spread from North America to Europe, Australasia and Latin America.[30][31][32]

Some explanations for the 2016 clown sightings phenomenon hypothesize that at least some of the sightings are part of a viral marketing campaign, possibly for the Rob Zombie film 31 (2016).[33] Greenville police chief Ken Miller said to reporters that investigators are unsure as to whether the sightings have any connection with Zombie's 31,[34] whether it was one or more people looking for "kicks", or something more sinister.[35]

A spokesperson for New Line Cinema (distributor of the 2017 film adaptation) released a statement claiming that "New Line is absolutely not involved in the rash of clown sightings."[36]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Radford, Benjamin (2016). Bad Clowns. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 29, 36, 67–69, 99–103. ISBN 9780826356673. https://books.google.com/books?id=KDyHCwAAQBAJ&pg=PAPA67. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "StephenKing.com - IT Inspiration". http://stephenking.com/library/novel/it_inspiration.html.

- ↑ Paquette, Jenifer (2012). Respecting The Stand: A Critical Analysis of Stephen King's Apocalyptic Novel. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. pp. 162–163. ISBN 0786470011. https://books.google.com/?id=U25SObo3cpoC&pg=PA162&lpg=PA162&dq=pennywise+john+wayne+gacy#v=onepage&q=pennywise%20john%20wayne%20gacy. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ "IT: CHAPTER 2 Announces Its Release Date" (in en). Nerdist. September 26, 2017. https://nerdist.com/it-chapter-two-release-date/.

- ↑ Kroll, Justin (June 2, 2016). "'It' Reboot Taps 'Hemlock Grove' Star Bill Skarsgard to Play Pennywise the Clown". Variety. https://variety.com/2016/film/news/it-reboot-pennywise-bill-skarsgard-1201766604/. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ↑ Squires, John (September 10, 2017). "Muschietti Talks Paintings that Inspired Nightmarish New 'IT' Creature". Bloody Disgusting. http://bloody-disgusting.com/movie/3458110/muschietti-talks-paintings-inspired-nightmarish-new-creature/. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ↑ Glenza, Jessica (2014-10-29). "The 10 most terrifying clowns" (in en-GB). The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/oct/29/the-10-most-terrifying-clowns-movies-film-tv.

- ↑ "10 Most Terrifying Clowns in Horror Movies" (in en-US). 2015-09-23. http://screenrant.com/scariest-clowns-horror-movies/?view=all.

- ↑ "The Scariest Clowns in Pop Culture". 2015-10-22. http://nerdist.com/the-scariest-clowns-in-pop-culture/.

- ↑ Gilbert, Sophie. "25 Years of Pennywise the Clown" (in en-US). https://www.theatlantic.com/notes/2015/11/20-years-of-pennywise-the-clown/416577/.

- ↑ Brottman, Mikita (2004). Funny Peculiar: Gershon Legman and the Psychopathology of Humor. London, England: Routledge. pp. 1. ISBN 0881634042. https://books.google.com/books?id=8i7vMDszCB8C&pg=PAPT79&dq=%22pennywise%2Bclown%2Bscariest%22&q=pennywise%2520clown+scariest. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Shan, Darren (October 29, 2019). "Mr Dowling wants to dance with YOU!". DarrenShan.com. Archived from the original on January 12, 2020. https://web.archive.org/web/20200112170326/https://www.darrenshan.com/news/article/mr-dowling-wants-to-dance-with-you. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ↑ Skal, David J. (2001). The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror. Macmillan. p. 363. ISBN 9780571199969. https://books.google.com/books?id=xwlNnOxMt1gC&pg=PAPA363. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "It". https://public.wsu.edu/~delahoyd/it.html.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "11 Creepy Facts About Stephen King's 'It'". http://diply.com/omg-facts/article/facts-about-stephen-king-it.

- ↑ Dery, Mark (1999). The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink. New York City: Grove Press. p. 70. ISBN 9780802136701. https://books.google.com/books?id=u71s2gNZqJoC&q=PennywisePennywise. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Frasier, David K. (2005). Suicide in the Entertainment Industry. McFarland. p. 314. ISBN 9780786423330. https://books.google.com/?id=97WJCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA314&lpg=PA314&dq=pennywise+band+stephen+king#v=onepage&q=pennywise%20band%20stephen%20king. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Burnham, Emily (September 8, 2016). "Stephen King weighs in on those creepy Carolina clown sightings". Bangor Daily News. Archived from the original on October 23, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161023051816/http://bangordailynews.com/2016/09/08/news/state/please-dont-send-in-the-clowns-stephen-king-reacts-to-carolina-scare/. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Stableford, Dylan (March 25, 2014). "Pennywise, the clown foolish?". https://www.yahoo.com/news/clown-staten-island-153044103.html.

- ↑ "At least 9 'clown' arrests so far in Alabama: What charges do they face?". http://www.al.com/news/birmingham/index.ssf/2016/09/nine_clown_arrests_so_far_in_a.html.

- ↑ Chan, Melissa. "Everything You Need to Know About the 'Clown Attack' Craze". http://time.com/4518456/scary-clown-sighting-attack-craze/.

- ↑ Flood, Alison (6 October 2016). "Stephen King tells US to 'cool the clown hysteria' after wave of sightings". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/oct/06/clown-sightings-stephen-king-it-pennywise. Retrieved 7 October 2016.

- ↑ Teague, Matthew (October 8, 2016). "Clown sightings: the day the craze began". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161018155654/https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2016/oct/05/clown-sightings-south-carolina-alabama. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Flood, Alison (October 6, 2016). "Stephen King tells US to 'cool the clown hysteria' after wave of sightings". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 15, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161015043726/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2016/oct/06/clown-sightings-stephen-king-it-pennywise. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Creepy clown sightings reported in more communities in South Carolina". WJW. September 2, 2016. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161104165505/http://fox8.com/2016/09/02/creepy-clown-sightings-reported-in-more-communities-in-south-carolina/. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Rogers, Katie (August 30, 2016). "Creepy Clown Sightings in South Carolina Cause a Frenzy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 3, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160903041841/http://www.nytimes.com/2016/08/31/us/creepy-clown-sightings-in-south-carolina-cause-a-frenzy.html. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Reuters (September 3, 2016). "Clown sightings spook South Carolina, perplex police". Yahoo!. Archived from the original on September 21, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20160921052256/https://www.yahoo.com/news/clown-sightings-spook-south-carolina-perplex-police-202822588.html. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Harris, Chris (September 2, 2016). "South Carolina Police Chief to Creepy Clowns: 'The Clowning Around Needs to Stop'". People. Archived from the original on October 23, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161023054730/http://people.com/crime/south-carolina-police-chief-says-clown-sightings-need-to-stop/. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Zuppello, Suzanne (September 29, 2016). "'Killer Clowns': Inside the Terrifying Hoax Sweeping America". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 21, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161021135025/http://www.rollingstone.com/culture/news/killer-clowns-inside-the-terrifying-hoax-sweeping-america-w442649. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Khomami, Nadia (October 10, 2016). "Creepy clown sightings spread to Britain". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 18, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161018155733/https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/oct/07/creepy-clown-sightings-craze-speads-britain. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ BBC Editors (October 7, 2016). "Clown sightings: Australia police 'won't tolerate' antics". BBC. Archived from the original on October 11, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161011143335/http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-australia-37586908. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ BBC Editors (October 20, 2016). "Creepy clowns: Professionals condemn scary sightings craze". BBC. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161022002358/http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-37718587. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Guarino, Ben (September 7, 2016). "Clown sightings have spread to North Carolina. Now police are concerned about creepy copycats". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 5, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161105060502/https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2016/09/07/clown-sightings-have-spread-to-north-carolina-now-police-are-concerned-about-creepy-copycats/. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Lee, Anna (September 1, 2016). "Police chief says clowns 'terrorizing public' will be arrested". The Greenville News. http://www.greenvilleonline.com/story/news/local/2016/09/01/sheriffs-office-police-address-clown-sightings/89729508/. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Reuters (September 4, 2016). "South Carolina clown sightings could be part of film marketing stunt". The Guardian. Archived from the original on October 23, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161023061627/https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/sep/04/south-carolina-clown-sightings-could-be-part-of-film-marketing-stunt. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

- ↑ Gardner, Chris (September 29, 2016). "Stephen King's 'It' Movie Producer Denies Creepy Clown Sightings Are Marketing Stunt". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. https://web.archive.org/web/20161022171057/http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/rambling-reporter/stephen-kings-movie-producer-denies-933077. Retrieved October 22, 2016.

External links