Biology:Cascade golden-mantled ground squirrel

| Cascade golden-mantled ground squirrel | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification Error creating thumbnail: Unable to save thumbnail to destination

| |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Rodentia |

| Family: | Sciuridae |

| Genus: | Callospermophilus |

| Species: | C. saturatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Callospermophilus saturatus (Rhoads, 1895)

| |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Spermophilus saturatus | |

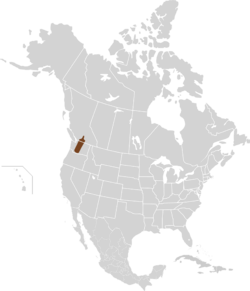

The Cascade golden-mantled ground squirrel (Callospermophilus saturatus) is a species of rodent in the family Sciuridae, in the order Rodentia.[2] It is the largest species of the three within the genus Callospermophilus.[2] It is found in the Cascade Mountains in the province of British Columbia, Canada and the state of Washington, United States .[1][3]

Morphology

Larger in size than its C. madrensis and C. lateralis counterparts, C. saturatus has a vague russet color outlining its head and shoulders and running down the length of its body (at least 286 mm).[2]

Distribution

C. saturatus occurs in the northwestern United States, north of the Columbia River, south of the Tulameen River in British Columbia, and west of the Similkameen River.[2] No fossils have yet been found.[2] C. saturatus is isolated from its sister species S. lateralis by the Columbia River; their differentiation is likely due to allopatric speciation.[4]

Physiology

At birth, C. saturatus are ectothermic.[5] Development of endothermy occurs gradually as individuals grow, increasing both body mass and amount of body fur.[5] Individuals removed from their mother at 6 days of age lost body temperature at a faster rate than at 36 days, when individuals were able to maintain a high internal body temperature and determined to be homeothermic.[5] This 36-day mark is conveniently the age at which offspring leave their burrows.[5] Individuals remained homeothermic in response to a 2-day removal of food and water at 2-week intervals.[5] Even with this drastically reduced body mass, torpor was not induced.[5] Smaller individuals did become hypothermic, however, and were returned to the mother to be re-warmed.[5]

Daily energy expenditures showed a small but significant increase of 10% as litter size increased, across a range of 3 to 5 offspring, the norm for the species.[6] Body mass, time spent above ground and time spent foraging were not correlated.[6] For the large amount energy contained in the mother's milk, changes in metabolism were small.[6] Body mass and age of offspring was independent of litter size.[6] The fact that daily energy expenditure does not vary with litter size suggests that other factors, such as habitat quality, affect number of offspring.[6]

C. saturatus have been noted to move in two distinct ways – walking (mean speed of .21 m/s) and running (mean speed of 3.63 m/s).[7] 26.9% of total time spent daily above ground was spent walking, while only 3.6% was spent running.[7] It is noted that individuals run at their maximum aerobic speed of 3.6 m/s instead of the more maintainable minimum running pace of 2 m/s in order to minimize predation.[7] C. saturatus moved an average of 5 km/day – 1.5 km walking and 3.3 km running.[7] This considerable distance required 28.75 kJ/day of net added energy cost to do so, a 29% increase above BMR and 13% of daily energy expenditure.[7]

Behavior

Examination of alarm calls in response to Canis lupus familiaris among several species of ground squirrels showed that C. saturatus have a dialect of their own.[4] Vocalizations were distinct, and could be identified 100% of the time by a discriminant source.[4] This suggests that vocalizations can be used in addition to genetics and morphology to differentiate and designate species.[4]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Cassola, F. (2016). "Callospermophilus saturatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T42562A22262657. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T42562A22262657.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/42562/22262657. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Trombulak, Stephen C. (27 December 1988). "Spermophilus saturatus". Mammalian Species (322): 1–4. doi:10.2307/3504256. http://www.science.smith.edu/resources/msi/pdfs/i0076-3519-322-01-0001.pdf.

- ↑ Helgen, Kristofer M.; Cole, F. Russel; Helgen, Lauren E.; Wilson, Don E (2009). "Generic Revision in the Holarctic Ground Squirrel Genus Spermophilus". Journal of Mammalogy 90 (2): 270–305. doi:10.1644/07-MAMM-A-309.1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Eiler, Karen Christine; Banack, Sandra Anne (Feb 2004). "Variability in the Alarm Call of Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrels (Spermophilus lateralis and S. saturatus)". Journal of Mammalogy 85 (1): 43–50. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2004)085<0043:vitaco>2.0.co;2.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Geiser, Fritz; Kenagy, G. J. (Aug 1990). "Development of Thermoregulation and Torpor in the Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrel Spermophilus saturatus". Journal of Mammalogy 71 (3): 286–290. doi:10.2307/1381938.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Kenagy, G. J.; Masman, D.; Sharbaugh, S. M.; Nagy, K. A. (Feb 1990). "Energy Expenditure During Lactation in Relation to Litter Size in Free-Living Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrels". Journal of Animal Ecology 59 (1): 73–88. doi:10.2307/5159.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Kenagy, G. J.; Hoyt, Donald F. (Dec 1989). "Speed and Time-Energy Budget for Locomotion in Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrels". Ecology 70 (6): 1834–1839. doi:10.2307/1938116.

External links

Wikidata ☰ {{{from}}} entry

|