Organization:Kriza János Ethnographic Society

Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság | |

| Abbreviation | KJNT |

|---|---|

| Named after | János Kriza |

| Formation | March 18, 1990[1] |

| Founded at | Cluj-Napoca |

| Type | scientific society |

| Purpose | ethnographic and athropological research, publishing, education |

| Headquarters | 15 Croitorilor Street, Cluj-Napoca, Romania |

| Fields | ethnography, anthropology |

Official language | hungarian |

President | Albert Zsolt Jakab |

| Website | www |

The Kriza János Ethnographic Society (Hungarian: Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság; abbreviated: KJNT) is ethnographical research institute founded in Cluj, Romania in 1990. Its objective is to serve as professional representation of the ethnic Hungarian ethnographers from Romania, and to provide an institutional framework for research and professional work.[2] Since its inception has been operating continuously, and as ethnographic research and ethnographic education began to develop, its activities expanded and diversified. From 1994 the Society has its own headquarters, where a library, an archive, a publisher and a lecture hall is housed. The latter is used for ethnographic lectures and exhibitions.[2]

History

After World War II, the communist regime terminated the ethnographic education at Bolyai University in 1948, leaving Hungarian ethnographic research in Romania without any background institution. Nevertheless, ethnography was included in the subjects of other faculties (history, humanities), and research and publications were published by various institutions until 1989.[3] After the Romanian Revolution the Hungarian ethnographers felt the need to set up a research organization, which represents and advocates their interests. The Kriza János Ethnographic Society was founded in Cluj-Napoca (Hungarian: Kolozsvár) on 18 March 1990. Its initiators included ethnographers Klára Gazda, Csilla Könczei, Ferenc Pozsony and Erzsébet Zakariás. Until 1994 the institute had its first seat in the apartment of Júlia Sigmond, a puppeteer from Cluj. The founder president was Ferenc Pozsony, the first secretary was Erzsébet Zakariás, and its first honorary president was István Almási,[4] followed by Iván Balassa (1991–2002).[5] The Society was named after the Unitarian bishop János Kriza, who was a well known Transylvaninan collector of folklore in the 19th century.

The goal of the founding Transylvanian intellectuals, teachers and museologists was to study folk culture, to process and preserve the material and intellectual heritage and to examine these professionally. In addition to regular field research, folklore collecting competitions, thematic professional conferences, seminars, exhibitions, publishing results, establishing a documentation center, the Society also intended to play a role in protecting the ethnographers interests and liaising with Hungarian ethnographic researchers and institutions in the Carpathian Basin. At the same time, as an educational and cultural background institution, they considered it important to contribute to the Hungarian-language ethnographic training at the University of Cluj.[1][2]

Since there were few opportunities for continuous professional relations between 1945 and 1989, the Kriza János Ethnographic Society organized 2–3 thematic conferences a year in various settlements in Transylvania. Researchers from Hungary also took an active part in this by transferring their knowledge, the latest research and interpretation methods of European ethnography. In the autumn of 1990, Professor János Péntek at the Babeș-Bolyai University restarted ethnographic education,[6] and since 1995 more and more young people with an ethnographic qualification have been admitted to educational, cultural, scientific and museal institutions in Romania. As Romanian scientific environment did not integrate the results of Hungarian researchers in the 1990s, the management of the Society sought to establish an independent center for science, documentation, culture and education. As a result of the work of József Kötő and Erzsébet Zakariás, with the support of the Illyés Foundation, the Kriza János Ethnographic Society moved into its real estate in 1994 in the center of Cluj. In its headquarters, the specialized library, archive, information-, education- and culture center were gradually built up. Mária Szikszai, Dóra Czégényi, Éva Borbély, Judit Keszeg and Erzsébet Tímea Tatár played a decisive role in the continuous processing and operation of the repository and the library.

In 2001, the Society also initiated the establishment of a Csángó museum. With the support of the Hungarian Ministry of National Cultural Heritage, the first permanent exhibition of the Csángó Ethnographic Museum was opened on 14 September 2003 in Zăbala. In 2004, with the support of the Apáczai Foundation, the mansard of the headquarters was converted to a space suitable for lectures and exhibitions. The reconstruction was led by Szabó Árpád Töhötöm.[1] In the same year, the Society was also a founding member of the Hungarian University Federation of Cluj, which serves as the background institution of Hungarian higher education in Cluj.[7][8]

Since 2011 the president of the Society is Jakab Albert Zsolt and honorary president is Ferenc Pozsony.[2]

In August 2013, the Company was recognized for its work for the Hungarians Abroad Award (Külhoni Magyarságért Díj) by the Prime Minister of Hungary.[9][10]

From 2015 the Society became the professional supervisor of the Transylvanian Value program (Erdélyi Értékek Tára), whose primary task is to launch, promote and organize the Hungarian National Value and Preservation Movement in Transylvania.[11][12][2]

Activities

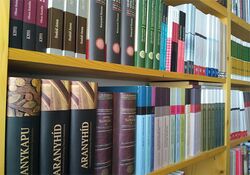

Library

The library was established first with publications from inheritances, and then, through various purchases, donations and book exchanges.[1] The library moved to its current location in 1994, where in addition to more than 10,000 books, the latest scientific periodicals are available. The volumes contain mainly the basic works of Hungarian and universal ethnography, but they also include works of social science (anthropology, sociology, history, linguistics, local history, literature). The bequests of renowned Transylvanian ethnographers (Károly Kós Jr., Jenő Nagy, Judit Szentimrei, Olga Nagy, József Faragó etc.) make up a very valuable part of the library. The books can be read in the two reading rooms available. The accessible stock is constantly expanding through contacts with institutions and publishers in the Carpathian Basin, and the results of scientific literature and researches are constantly enriching the library.[2][13] Since 2007 the library catalog is available on the Society's website, where the most important information about the items (author, editor, title, publisher, place of publication) can be searched.[14]

Documentation repository

The institution's ever-expanding repository of manuscripts and student papers is an important source of ethnological work. Thousands of manuscripts, sound and motion pictures can be found here. The manuscripts include the material of renowned researchers such as Károly Kós Jr., József Faragó, Jenő Nagy, László Székely, Judit Szentimrei and Géza Vámszer. Within the framework of a multiannual project, the digitization of the material of the most important inheritances as well as ethnographic collections is ongoing and will be made available in the form of a digital archive. The Csángó Archive exists as a separate division and is constantly expanding, containing more than two thousand items, manuscripts, rare publications, maps, other documents in Hungarian, Romanian, English and German. This is also considered an important collection by scholars of the Csángó topic.[2][15]

Conferences

Scientific conferences have been an important part of the Society's activities since its inception in 1990. The conferences discussed topics such as Hungarian ethnographic research in Romania, carnivals, beliefs and belief figures, folk society and folk morality, oral history, use of space in culture, handicraft, plants and culture, dance and community, nativity plays, woman's place in society, literacy and written folklore, diaspora research, cohabitation models in Transylvanian villages, spring folk traditions, rural ethnographic collections, folk music, folk decorative arts, migration, Moldavian Csángó research, folk medicine, Transylvanian pottery, play and culture, rites of passage, change in farm structure, folk religiosity, Transylvanian Gypsies, life story, subcultures, military, culture and economy, demography, museology, Hungarology, social networks, cultural heritage, traditions, research methodology and data protection, ethnographical research history, ethnographical archives etc.[16][17]

Exhibitions, events, scientific college

In addition to the scientific conferences, the headquarters hosts several temporary exhibitions, book presentations, film screenings, and roundtables. As a background institution for Hungarian ethnographic education in Cluj, series of lectures are organized to complement the ethnographic curriculum. The lecturers are guest teachers, professionals, researchers from Transylvania and Hungary.[8][17]

An important part of beenig a background institution is the support and operation of the Kriza János Scientific College (Kriza János Szakkollégium).[18] This is an interdisciplinary training which tutors a young research community. The scientific college operates in a tutoring system, and it is used for lectures, professional consultation, joint and individual research. The college events take place at the Society's headquarters and the invited speakers use the lecture hall.[8]

Databases

Bibliographical databases

After its foundation, the Society started to organize the results of its research and fieldwork. In addition to the continuous compilation and publication of personal, thematic or regional bibliographies, in 2008 the Bibliography of the Moldavian Csángós (redacted by Sándor Ilyés) and The Hungarian Ethnographic Bibliography of Romania (redacted by Albert Zsolt Jakab) became available on the Society's websitea. Each of these items contains the most important bibliographic information, and the material can be listed by year, title, or topic.[2][1]

Ballad Repertory

Created in 2013, the digital ballad repertory (Balladatár) contains materials from Hungarian ballad collections in Transylvania and Moldavia, grouped by type and subtype, with bibliographic data and sheet music.[15][19]

Transylvanian Values Collection

In 2015, the Society launched the Transylvanian Values Collection (Erdélyi Értékek Tára) to monitor, support and display the results of the Transylvanian value exploration movement. The database archives the values accepted by the Transylvanian Hungarian Values Committee, and the main topics are: agro- and food industry, industrial and technical solutions, natural environment, health and lifestyle, cultural heritage, tourism and hospitality, built environment, sport.[15]

Ethnographic Museums Collection

In 2014, the Society launched the Ethnographic Museums Collection (Néprajzi Múzeumok Tára), which contains data and information about country house museums, guild history museums, memorial halls / memorial rooms, local history museums, ethnographic museums, ethnographic rooms and ethnographic collections in Transylvania and the Partium region.[15][20]

Photo archive

The photo archive, launched in 2008, contains the Society's digitized negative collection. The database contains photographs of ethnographic subjects dating from the 1910s, from well known researchers and photographs such as Béla Gunda, László Seiwarth, Károly Kós, Géza Vámszer, Jenő Nagy, Tamás Szabó, László Péterfy, and other researchers and students of the Society and the Department of Hungarian Ethnography and Anthropology of the Babeș-Bolyai University. Part of these digitized photos were made on field research in Transylvania and Moldavia.[15][21]

Text Collection

In 2016 the Society began a program for digital processing of the books published. These are published online the database called Text Collection (Szövegtár) which contains not only publications but also the authors' data sheets.[15]

Publishing

From the outset, publishing has been a major task for the Society. Depending on the possibilities, 5–10 volumes are published each year. These books ensure the presentation of the latest results of the Hungarian ethnographic research in Romania and the work of the Society's members.

The yearbook series contains mostly materials of conferences, the Kriza Books series displays the ethnographic fieldwork, study and interpretation, the Kriza Library series provides the publication of sources and folklore texts. The volumes of the Courses in Ethnography series, launched in 2006, are used as textbooks in ethnographic education at universities. A new series from 2018, Dissertationes Ethnographicæ Transylvanicæ, features doctoral theses, basic ethnographic and anthropological works. In addition to these, science history and science theory volumes, special volumes and bibliographies are published outside the series. In many cases these are published with other institutions and publishers. The Society had a successful partnership with the late Mentor publishing house, resulting in ethnographic works by the Society's researchers and members in the Library of the Kriza János Ethnographic Society series. Bulletin of the Society reached 16 appearances so far.[2][22]

The publications reach all important institutions of ethnography, university departments, research institutes, museums and specialized libraries in Romania and Hungary. These volumes can also be found in national and regional public libraries, libraries of NGOs, smaller ethnographic and social science units. The newly published publications are presented at the Society's headquarters and other partner institutions.[2]

Since 2016, the digital version of the publications are available in the Text Collection (Publisher and Researcher Database). This can be searched by title, author, subject, year of publication, or location, and all texts are available in PDF format. It also serves as a research database for information on researchers who published at the Society.[15][23]

Projects

Since its foundation, the Society has undertaken and carried out several projects and researches.[12]

- Preliminary work on the ethnography of Hungarians in Romania: the researchers of the Society collected, systematized and prepared for publication the ethnographic bibliography of Hungarians in Romania.

- The Society undertook several current researches in the Moldavian Csángó communities with the aim of ethnographic and anthropological examination of the social structure of the researched villages, the collection of texts and language relicts, and the professional documentation of acculturation and identity change.

- During the Moldavian linguistic geography research jointly launched with ELTE Department of Linguistics, the linguistic status of Moldavian Csángó villages was researched and digitally recorded.

- During the analysis of the economic models of the Transylvanian villages, the researchers of the Society carried out a study of the parallel presenc of the new mentality and strategies and the old patterns in these communities. In addition, they sought answers to the problems and prospects of the economic structure of Hungarian rural communities in Transylvania, and to what factors help or hinder the development of the rural region.

- The project investigating the structure of transforming localities seeks to find out what local identities develop in the Transylvanian worlds as a result of and in the face of national discourses and national aspirations. At the same time the project examines the public events, narratives, and narrative constructs in which localities appear.

- Impact assessment of the motorway to be built through Northern Transylvania: study of the culture of the affected settlements, with an emphasis on de-traditionalization and tradition-building, and on how the different levels of rural life in a modernization project of this size are transformed.

- The aim of the research in Aranyos Seat is to explore the cultural and economic traditions of the region.

- In 2006, a large-scale project entitled Digital display of the Transylvanian and Moldavian ethnographic heritage was launched to develop digital and online archives.

- Since 2015, the Transylvanian Value project has been the Society's flagship project. Its primary task is to launch, popularize, organize and professionally supervise the Hungarian national values and preservation movement in Transylvania. On behalf of the Hungarian Ministry of Agriculture and the Hungaricum Committee, the Society provides professional and methodological assistance to NGOs to locate, professionally document, archive and integrate local and regional values into the daily lives of local communities. The Society offers on-site lectures and trainers, methodological aids and training materials, as well as professional advice on the process of valuation and preparation of proposals. During the project professional conferences, methodological trainings, presentations and exhibitions are organized in Transylvania and Moldavia. As a result, the Transylvanian Values Collection website was launched, which archives the values accepted by the Transylvanian Hungarian Depository Committee[11][12][2]

Partners

The most important professional partner of the Society is the Department of Hungarian Ethnography and Anthropology of the Babeș-Bolyai University, of which the Kriza János Ethnographic Society is a background institution. In addition, there have been effective professional relationships with a number of professional organizations and institutions from Romania and Hungary:[24]

- Hungarian Ethnographic Society, Budapest

- Ethnographic Museum, Budapest

- Hungarian Open Air Museum, Szentendre

- Csángó Ethnographic Museum, Zăbala

- Székely National Museum, Sfântu Gheorghe

- Tarisznyás Márton Museum, Gheorgheni

- Szekler Museum of Ciuc, Miercurea Ciuc

- Arad Museum Complex, Arad

- Satu Mare County Museum, Satu Mare

- Ethnographic Museum of Transylvania, Cluj-Napoca

- Transylvanian Museum Society, Cluj-Napoca

- Hungarian Academy of Sciences – Institute of Ethnology, Budapest

- Hungarian Academy of Sciences – Institute for Minority Studies, Budapest

- National Institute for Culture, Budapest

- ELTE Institute of Ethnography and Folklore, Budapest

- University of Debrecen, Department of Ethnology, Debrecen

- University of Szeged, Department of Ethnology and Cultural Anthropology, Szeged

- University of Pécs, Department of Ethnography and Cultural Anthropology, Pécs

- Hungarian University Federation of Cluj, Cluj-Napoca

- Romanian Institute for Research on National Minorities, Cluj-Napoca

- UBB Department of Sociology and Social Work in Hungarian, Cluj-Napoca

- Heritage House, Budapest

Lifetime Award

Since 2012 the Society honored many Transylvanian ethnographers, who contributed significantly to the research of the ethnic Hungarian folk culture with the Lifetime Award (Életmű-díj).[13]

- 2012 – Árpád Daczó (P. Lukács OFM)

- 2013 – Piroska Kovács

- 2014 – István Almási

- 2015 – Judit Szentimrei

- 2016 – Zoltán Kallós

- 2017 – Ernő Albert

- 2017 – László Barabás

- 2017 – János Ráduly

- 2018 – Klára Gazda

- 2019 – Péter Halász

See also

- Hungarians in Romania

- Hungarian folk music

- Ethnology

- Székelys

- Csángó

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Ferenc Pozsony (2010). "Bevezető". in Albert Zsolt Jakab – Sándor Ilyés (PDF). 20 éves a Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság. KJNT. pp. 3–5. http://kjnt.ro/szovegtar/pdf/KJNTErt_15_1-2_2010_IlyesS-JakabAZs_szerk_20-eves-a-KJNT. Retrieved 28 June 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 Sándor Ilyés – Albert Zsolt Jakab (2018). "A Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság". Korunk 29 (10): 36–42. http://epa.oszk.hu/00400/00458/00647/pdf/EPA00458_korunk-10-2018_036-042.pdf. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ Ernő Albert (2012–2013). "Faragó József (1922–2004)". Acta Siculica (Székely Nemzeti Múzeum): 581–597. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "Elhunyt Almási István népzenekutató, Társaságunk alapító tagja". KJNT. 2021-03-08. http://www.kjnt.ro/infoteka/280. Retrieved 2021-03-09. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ Lajos Balázs. "A Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság gyergyószentmiklósi vándorgyűlése". Néprajzi Hírek XX (2–3): 76. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ János Péntek. "A harmadik (újra)kezdés". in Vilmos Keszeg – István Szilárd Szász – Júlia Zsigmond (PDF). Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság Évkönyve 22. Néprajzi intézmények, kutatások, életpályák. KJNT. pp. 279–290. ISBN 978-973-8439-75-7. http://kjnt.ro/szovegtar/pdf/KJNTEvk_22_2014_KV-SzISz-ZsJ_szerk_Neprajzi_08_PentekJ. Retrieved 22 July 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "Mi a KMEI?". KMEI. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20190419001330/http://kmei.ro/mi-a-kmei/. Retrieved 4 September 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Sándor Illyés (2015). "A Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság". Művelődés 69 (3). Archived from the original on 8 December 2019. https://web.archive.org/web/20191208170010/https://muvelodes.net/m/a-kriza-janos-neprajzi-tarsasag. Retrieved 28 June 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "Külhoni Magyarságért Díjat kapott a KJNT". KJNT. 20 August 2013. http://www.kjnt.ro/infoteka/112. Retrieved 4 September 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "Külhoni Magyarságért Díj". kormany.hu. https://augusztus20.kormany.hu/akadalymentes/kulhoni-magyarsagert-dij-2013. Retrieved 4 September 2019.(in Hungarian)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Erdélyi Értékek Tára". KJNT. http://www.kjnt.ro/ertektar/. Retrieved 8 December 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Projektek". KJNT. http://www.kjnt.ro/projektek. Retrieved 8 December 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "Rólunk". KJNT. http://www.kjnt.ro/rolunk. Retrieved 7 July 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "Online library catalog". http://www.kjnt.ro/konyvtari-katalogus. Retrieved 22 July 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 Albert Zsolt Jakab (2017). "Néprajzi archívumok új környezetben. Az erdélyi és moldvai magyar kultúra kutatásának és archiválásának kihívásai". in Albert Zsolt Jakab – András Vajda. Örökség, archívum és reprezentáció (Kriza Könyvek, 40.). Kolozsvár: KJNT. pp. 185–222. http://kjnt.ro/szovegtar/pdf/KKonyvek_40_2017_JAZs-VA_szerk_Orokseg_11_JakabAZs1. Retrieved 28 June 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ Albert Zsolt Jakab – Sándor Ilyés, ed (2010). "A KJNT szakmai konferenciái" (PDF). 20 éves a Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság. KJNT. pp. 15–18. http://kjnt.ro/szovegtar/pdf/KJNTErt_15_1-2_2010_IlyesS-JakabAZs_szerk_20-eves-a-KJNT. Retrieved 28 June 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Infótéka". KJNT. http://www.kjnt.ro/infoteka. Retrieved 22 July 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "Kriza János Szakkollégium". https://www.facebook.com/krizajanosszakkollegium/. Retrieved 4 September 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "Balladatár". KJNT. http://www.kjnt.ro/balladatar/. Retrieved 8 December 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "Néprajzi Múzeumok Tára". KJNT. http://www.kjnt.ro/muzeumtar/. Retrieved 8 December 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "A fotóarchívum". KJNT. http://www.kjnt.ro/fotoarchivum/archivumrol.php. Retrieved 8 December 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "Kiadó". KJNT. http://www.kjnt.ro/kiado. Retrieved 22 July 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "Szövegtár (Kiadói és kutatói adatbázis)". KJNT. http://www.kjnt.ro/szovegtar/. Retrieved 8 December 2019. (in Hungarian)

- ↑ "Partnerek". KJNT. http://www.kjnt.ro/partnerek. Retrieved 22 July 2019. (in Hungarian)

Articles

- Sándor Ilyés – Albert Zsolt Jakab (eds.): 20 éves a Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság (Bulletin of the Kriza János Ethnographic Society. Vol. XV. Nr. 1–2. 20 Years – Kriza János Ethnographic Society.). Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság, Kolozsvár, 2010. (in Hungarian)

- Sándor Ilyés – Albert Zsolt Jakab: A Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság (The Kriza János Ethnographic Society). Korunk, 2018/10. 36–42. (in Hungarian)

- Albert Zsolt Jakab: Néprajzi archívumok új környezetben. Az erdélyi és moldvai magyar kultúra kutatásának és archiválásának kihívásai (Ethnographic Archives in Newest Contexts. Challenges of the Research and Archiving of Transylvanian and Moldavian Hungarian Culture). In: Albert Zsolt Jakab – András Vajda (eds.): Örökség, archívum és reprezentáció (Kriza Könyvek, 40.) (Heritage, Archives and Representations (Kriza Books Nr. 40)). Kriza János Néprajzi Társaság, Kolozsvár, 185–222. (in Hungarian)

- László Barabás: A néprajzban valami elkezdődött (Something has started in the ethnography). Erdélyi Figyelő, 1991/8. (in Hungarian)

- Erzsébet Zakariás: A KJNT idei első vándorgyűlése (This year's first assembly of the KJES). Művelődés, 1992/4. (in Hungarian)

External links

- Official website (in Hungarian, Romanian, and English)

- The Kriza János Ethnographic Society on Facebook-on (in Hungarian)

- Website of the Transylvanian Values (Erdélyi Értékek Tára) (in Hungarian)

- The Society's digitized publications (in Hungarian, Romanian, and English)

- The Society's photo archive (in Hungarian)

[ ⚑ ] 46°46′31.7″N 23°35′33.2″E / 46.775472°N 23.592556°E

|