Biology:Indiana bat

| Indiana bat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Chiroptera |

| Family: | Vespertilionidae |

| Genus: | Myotis |

| Species: | M. sodalis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Myotis sodalis Miller & Allen, 1928

| |

| |

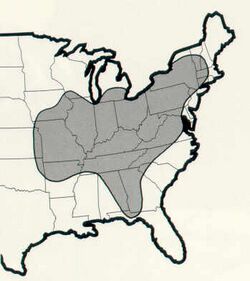

| Approximate range of the Indiana bat | |

The Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) is a medium-sized mouse-eared bat native to North America. It lives primarily in Southern and Midwestern U.S. states and is listed as an endangered species. The Indiana bat is grey, black, or chestnut in color and is 1.2–2.0 in long and weighs 4.5–9.5 g (0.16–0.34 oz). It is similar in appearance to the more common little brown bat, but is distinguished by its feet size, toe hair length, pink lips, and a keel on the calcar.

Indiana bats live in hardwood and hardwood-pine forests. It is common in old-growth forest and in agricultural land, mainly in forest, crop fields, and grasslands. As an insectivore, the bat eats both terrestrial and aquatic flying insects, such as moths, beetles, mosquitoes, and midges.

The Indiana bat is listed as an endangered species by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. It has had serious population decline, estimated to be more than 50% over the past 10 years, based on direct observation and a decline on its extent of occurrence.[1]

Description

The length of the Indiana bat's head to the body is from 4.1 to 4.9 cm. The animal weighs about 8 g (.25 ounce). These bats are very difficult to distinguish from other species, especially the more common little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus), unless examined closely. The size of the feet, the length of the toe hairs, and the presence of a keel on the calcar are characteristics used to differentiate the Indiana bat from other bats. Indiana bats typically live 5 to 9 years, but some have reached 12 years of age. They can have fur from black to chestnut with a light gray to cinnamon belly. Unlike other common bats with brown hair and black lips, Indiana bats have brown hair and pink lips, which is helpful for identification.

Distribution

Indiana bats spend the summer living throughout the eastern United States. During winter, however, they cluster together and hibernate in only a few caves. Since about 1975, their population has declined by about 50%. Based on a 1985 census of hibernating bats, the Indiana bat population is estimated around 244,000. About 23% of these bats hibernate in caves in Indiana . The Indiana bat lives in caves only in winter; but, there are few caves that provide the conditions necessary for hibernation. Stable, low temperatures are required to allow the bats to reduce their metabolic rates and conserve fat reserves. These bats hibernate in large, tight clusters which may contain thousands of individuals. Indiana bats feed entirely on night flying insects, and a colony of bats can consume millions of insects each night.[citation needed] The range of the Indiana bat overlaps with that of the more narrowly distributed gray bat (Myotis grisescens), also listed as endangered.

Endangered status

The Indiana bat was listed as federally endangered under the Endangered Species Preservation Act, on 11 March 1967, due to the dramatic decline of populations throughout their range. Reasons for the bat's decline include disturbance of colonies by human beings, pesticide use and loss of summer habitat resulting from the clearing of forest cover. As of 1973, the Indiana bat has been listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (as amended), and additionally protected by the Federal Cave Resources Protection Act of 1988, to protect hibernacula on federal lands. In 2013, Bat Conservation International listed this species as one of the 35 species of its worldwide priority list of conservation.[2]

Current threats

Indiana bat populations in the northeastern United States are crashing with the rapid spread of white-nose syndrome, the most devastating wildlife disease in recent history. By the end of 2011, this unprecedented threat had killed 5.7 to 6.7 million bats in the United States since its discovery in 2007 based on photographs taken in 2006.[3] Among these, at least 15,662 Indiana bats died from WNS in 2008 alone (3.3% of the 2007 range wide population), and an estimated 95% of Pennsylvania's entire cave bat population has died.[4][5]

Although becoming less common, direct and intentional killings by humans have occurred. On 23 October 2007, Lonnie W. Skaggs of Olive Hill, Kentucky, and Kaleb Dee Carpenter, of Grayson, Kentucky, entered Laurel Cave in Carter Caves State Park, Kentucky, and killed 23 Indiana bats. Skaggs re-entered the cave three days later and killed another 82 endangered Indiana bats. An investigation began when Carter Caves State Park employees discovered at least 105 dead Indiana bats. The two men admitted to knowingly slaughtering an endangered species, using flashlights and rocks to knock hibernating bats off their roosts, and smashing their bodies with rocks. Bats that attempted to escape by flying away were knocked down from the air. The men stomped bats to death, bludgeoned them with flashlights, and crushed their bodies with rocks in several areas of the hibernaculum. BCI worked with the Kentucky Department of Fish & Wildlife Resources to establish a reward fund and provided the initial contribution. The reward quickly grew to $5,000 with support from the Southeastern Bat Diversity Network and Defenders of Wildlife and was widely reported, and the two men were caught following an anonymous tip. This incident was called a "senseless killing" by James Gale, Special Agent-in-Charge for the USFWS Southeast Region, and resulted in conviction. They pleaded guilty to violating the federal Endangered Species Act. U.S. Magistrate Judge Edward Atkins sentenced Skaggs to eight months in federal prison, and placed Carpenter on three years' probation. The case marks the first time nationwide that individuals were sentenced for killing endangered Indiana bats. BCI thanked members and donors for allowing them to help protect these bats and work toward a time when such killings finally cease.[6][7]

Additionally, Indiana bat mortality due to wind turbines has been confirmed, even resulting in a December 2009 injunction against a West Virginia wind farm.[8] As of 2013, only five Indiana bat mortalities have been documented; two females at Fowler Ridge in Indiana in September 2009 and 2010, one female at the North Allegheny Wind Energy Facility, Pennsylvania, in September 2011,[9] one male at the Laurel Mountain Wind Power facility, West Virginia in July 2012, and one female at the Blue Creek Wind Farm, Ohio in October 2012.[10] Fatality rates of up to 63.9 bats per turbine, per year have been estimated.[11] Mortality is caused both by direct impact with rotors and by barotrauma.[12]

Other anthropogenic effects have contributed to the loss of Indiana bat populations, including pesticide use, human disturbance of hibernacula, improper application of cave gates, climate change, and agricultural development. As a result, the Indiana bat experienced a nationwide 57% population decline from 1960 to 2001.[13]

Plant communities

Common dominant trees used by Indiana bats throughout their range include oaks (Quercus spp.), hickories (Carya spp.), ashes (Fraxinus spp.), elms (Ulmus spp.), eastern cottonwoods (Populus deltoides), locusts (Robinia spp.), and maples (Acer spp.). The understory may include hawthorns (Crataegus spp.), dogwoods (Cornus spp.), fragrant sumac (Rhus aromatica), giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida), sedges (Carex spp.), Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia), wood nettle (Laportea canadensis), goldenrod (Solidago spp.), poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans), and wild grape (Vitis spp.).[14]

Indiana bats were found in a variety of plant associations in a southern Iowa study. Riparian areas were dominated by eastern cottonwood, hackberry (Celtis occidentalis), and silver maple (Acer saccharinum). In the forested floodplains, the dominant plants included black walnut (Juglans nigra), silver maple, American elm (Ulmus americana), and eastern cottonwood. In undisturbed upland forest, the most common plants were black oak (Quercus velutina), bur oak (Q. macrocarpa), shagbark hickory (Carya ovata), and bitternut hickory (C. cordiformis). Black walnut, American basswood, American elm, and bur oak dominated other upland Indiana bat sites.[15]

Indiana bats use at least 29 tree species during the summer. The greatest numbers of tree species are found in the central portion of Indiana bats' range (primarily Missouri, southern Illinois, southern Indiana, and Kentucky), but this is likely because the majority of research conducted on the species has occurred in this region. Roost trees from these central states, which are mainly in the oak-hickory cover type, include silver maple, red maple (Acer rubrum), sugar maple (A. saccharum), white oak (Q. alba), red oak (Q. rubra), pin oak (Q. palustris), scarlet oak (Q. coccinea), post oak (Q. stellata), shingle oak (Q. imbricaria), eastern cottonwood, shagbark hickory, bitternut hickory, mockernut hickory (C. alba), pignut hickory (C. glabra), American elm, slippery elm (Ulmus rubra), honey locust (Gleditsia triacanthos), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica), white ash (F. americana), Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana), American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis), and sassafras (Sassafras albidum).[14][16][17][18][19][20][21][22]

In southern Michigan and northern Indiana, which are mainly in the oak-hickory and elm-ash-cottonwood cover types, trees used as roosts include green, white, and black ash (Fraxinus nigra), silver maple, shagbark hickory, and American elm.[23] And finally, in the southern areas of the Indiana bat's range (primarily Tennessee, Arkansas, and northern Alabama), which include the oak-hickory and oak-pine cover types, Indiana bats use shagbark hickory, white oak, red oak, pitch pine (P. rigida), shortleaf pine (P. echinata), loblolly pine (P. taeda), sweet birch (Betula lenta), and eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis).[24][25]

Major life events

Indiana bats begin to arrive at hibernacula (caves and mines in which they spend the winter) from their summer roosting sites in late August, with most returning in September. Females enter hibernation shortly after arriving at hibernacula, but males remain active until late autumn to breed with females arriving late. Most Indiana bats hibernate from October through April, but many at the northern extent of their range hibernate from September to May. Occasionally, Indiana bats are found hibernating singly, but almost all are found hibernating in dense clusters of 3,230 to 5,215 bats/m2.[26]

Spring migration can begin as early as late March, but most Indiana bats do not leave their winter hibernacula until late April to early May. Females emerge from hibernacula first, usually between late March and early May. Most males do not begin to emerge until mid- to late April.[26][27] Females arrive at summer locations beginning in mid-April. Females form summer nursery colonies of up to 100 adult females during summer.[21][26] Males typically roost alone or in small bachelor groups during the summer. Many males spend the summer near their winter hibernacula, while others migrate to other areas, similar to areas used by females.[26]

Females can mate during their first fall, but some do not breed until their second year.[26][28] Males become reproductively active during their second year.[26] Breeding occurs in and around hibernacula in fall.[26] During the breeding season, Indiana bats undergo a phenomenon known as swarming. During this activity, large numbers of bats fly in and out of caves from sunset to sunrise.[26] Swarming mainly occurs during August to September and is thought to be an integral part of mating.[26] Bats have been observed copulating in caves until early October. During the swarming/breeding period, very few bats are found roosting within the hibernacula during the day. Limited mating may also occur at the end of hibernation.[26]

Fertilization does not occur until the end of hibernation,[26][28] and gestation takes about 60 days. Parturition occurs in late May to early July.[26][28] Female Indiana bats typically give birth to one pup.[26][28] Juveniles are weaned after 25 to 37 days [20] and are able to fly around the same time.[26] Most young can fly by early to late July,[20] but sometimes do not fly until early August.[28] Humphrey and others [20] reported an 8% mortality rate by the time young were weaned. However, they assumed that all females mate in the autumn,[28] which is not the case, so not all the females would give birth. Thus, mortality of young may be even lower than 8%.

Indiana bats are relatively long lived. One Indiana bat was captured 20 years after being banded as an adult.[27] Data from other recaptured individuals show that females live at least 14 years 9 months, while males may live for at least 13 years 10 months.[29]

Habitat

Landscape

Habitat requirements for the Indiana bat are not completely understood. Bottomland and floodplain forests were once thought to be the most important habitats during the summer, but subsequent study has shown that upland forest habitats may be equally important, especially in the southern portions of the species's range.[14][15][16] Indiana bats are found in hardwood forests throughout most of their range [14][20] and mixed hardwood-pine forests in the southeastern United States.[22][24] Stone and Battle [25] found a significantly greater proportion (p<0.05) of old-growth forest (greater than 100 years), more hardwoods, and fewer conifers in stands occupied by Indiana bats than in random stands in Alabama.

In an Illinois study by Gardner and others,[14] the study area where Indiana bats were found was estimated as roughly 67% agricultural land including cropland and old fields; 30% was upland forest; while 2.2% was floodplain forest. Finally, only 0.1% of the area was covered with water. Kurta and others [30] found that in southern Michigan, the general landscape occupied by Indiana bats consisted of open fields and agricultural lands (55%), wetlands and lowland forest (19%), other forested habitats (17%), developed areas (6%), and perennial water sources such as ponds and streams (3%).

In southern Illinois, Carter and others [17] reported that all roosts were located in bottomland, swamp, and floodplain areas. Miller and others [31] determined the predominant habitat types near areas where Indiana bats were captured in Missouri were forest, crop fields, and grasslands. Indiana bats did not show any preference for early successional habitats, such as old fields, shrublands, and early successional forests, showing 71% to 75% of activity occurring in other habitats. Although much of the landscape throughout the distributional range of the Indiana bat is dominated by agricultural lands and other open areas, these areas are typically not used by Indiana bats.[20][32]

Indiana bats typically spend the winter in caves or mines. However, a few bats have been found hibernating on a dam in northern Michigan. They need very specific conditions to survive the winter hibernation period, which lasts about 6 months. As the microclimate in a hibernaculum fluctuates throughout the winter, Indiana bats sometimes fly to different areas within the hibernaculum to find optimal conditions,[33] but this does not appear necessary for every hibernaculum. Indiana bats may even switch between nearby hibernacula in search of the most appropriate hibernating conditions.[27] Indiana bats are generally loyal to specific hibernacula or to the general area near hibernacula that they have occupied previously.[27] Critical winter habitats of Indiana bats have been designated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and include 13 hibernacula distributed across Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, Tennessee, and West Virginia.[34]

Three types of hibernacula have been designated depending on the amount of use each receives from year to year. Priority one hibernacula are those that consistently have greater than 30,000 Indiana bats hibernating inside each winter. Priority two hibernacula contain 500 to 30,000 bats, and priority three hibernacula are any with fewer than 500 bats. At least 50% of Indiana bats are thought to hibernate in the eight priority one hibernacula, which can be found in Indiana (three), Missouri (three), and Kentucky (two). Estimates of hibernating populations in 2001 suggest that priority one hibernacula have experienced a 48% decline since 1983. Overall, populations have fallen around 57% since 1960 across all hibernacula.[13]

Site characteristics

Studies have identified at least 29 tree species used by Indiana bats during the summer and during spring and fall migrations. Since so many tree species are used as roosts, tree species is likely not a limiting habitat requirement. In addition to trees, Indiana bats have used a Pennsylvania church attic, a utility pole,[25] and bat boxes [35] as roosts. However, use of man-made structures appears to be rare. Roost selection by females may be related to environmental factors, especially weather. Cool temperatures can slow fetal development,[20] so choosing roosts with appropriate conditions is essential for reproductive success [26] and probably influences roost choice.

Two types of day roosts used by Indiana bats have been identified as primary and alternate roosts. Primary roosts typically support more than 30 bats at a time[31] and are used most often by a maternity colony. Trees that support smaller numbers of Indiana bats from the same maternity colony are designated as alternate roosts. In cases where smaller maternity colonies are present in an area, primary roosts may be defined as those used for more than 2 days at a time by each bat, while alternate roosts are generally used 1 day.[24] Maternity colonies may use up to three primary roosts and up to 33 alternate roosts [18][31] in a single season. Reproductively active females frequently switch roosts to find optimal roosting conditions. When switching between day roosts, Indiana bats may travel as little as 23 feet (7.0 m) or as far as 3.6 miles (5.8 km).[30] In general, moves are relatively short and typically less than 0.6 miles (0.97 km).[36]

Primary roosts are most often found at forest edges or in canopy gaps.[16][31] Alternate roosts are generally located in a shaded portion of the interior forest and occasionally at the forest edge.[16] Most roost trees in a Kentucky study occurred in canopy gaps in oak, oak-hickory, oak-pine, and oak-poplar community types.[21] Roosts found by Kurta and others [30] in an elm-ash-maple forest in Michigan were in a woodland/marsh edge, a lowland hardwood forest, small wetlands, a shrub wetland/cornfield edge, and a small woodlot. Around hibernacula in autumn, Indiana bats tended to choose roost trees on upper slopes and ridges that were exposed to direct sunlight throughout the day.[21]

The preferred amount of canopy cover at the roost is unclear. Many studies have reported the need for low cover, while others have documented use of trees with moderate to high canopy cover, occasionally up to complete canopy closure. Canopy cover ranges from 0% at the forest edge to 100% in the interior of the stand.[14][16][22] A general trend is that primary roosts are found in low cover, while alternate roosts tend to be more shaded. Few data directly compare the differences between roost types. In Alabama, canopy cover at the roost tended to be low at an average of 35.5%, but at the stand level, canopy cover was higher with a mean of 65.8%.[25] In a habitat suitability model, Romme and others [37] recommended the ideal canopy cover for roosting Indiana bats as 60% to 80%. Actual roost sites in eastern Tennessee were very high in the tree, and Indiana bats were able to exit the roost above the surrounding canopy. Thus, canopy cover measurements taken from the bases of roost trees may overestimate the actual amount of cover required by roosting Indiana bats.[24]

Stands occupied by this species can vary greatly. A Virginia pine roost was in a stand with a density of only 367 trees/ha,[38] while in Kentucky, a shagbark hickory roost was in a closed-canopy stand with 1,210 trees/ha.[21] Overall tree density in Great Smoky Mountain National Park was higher around primary roosts than at alternate roosts.[24] At the landscape level, the basal area for stands with roosts was 30% lower than basal area of random stands in Alabama.[25] Tree density in southern Iowa varied between different habitats. In a forested floodplain, tree density was lowest at 229 trees/ha, while a riparian strip had the highest tree density at 493 trees/ha.[15]

The number of roosts used and home range occupied by a maternity colony can vary widely. In Missouri,[16] the highest density of roosts being used in an oak-hickory stand was 0.25 tree/ha. In Michigan, the number of trees used by a colony was 4.6 trees/ha, with as many as 13.2 potential roosts/ha in the green ash-silver maple stand. Clark and others [15] estimated that the density of potential roosts in southern Iowa in areas where Indiana bats were caught was 10 to 26/ha in riparian, floodplain, and upland areas dominated by eastern cottonwood-silver maple, oak-hickory, and black walnut-silver maple-American elm, respectively. In Illinois, the suggested optimal number of potential roost trees in an upland oak-hickory habitat was 64/ha; the optimal number for riparian and floodplain forest, dominated by silver maple and eastern cottonwood, was proposed to be 41/ha.[14]

Salyers and others [35] suggested a potential roost density of 15 trees/ha was needed, or 30 roosts/ha if artificial roost boxes are erected in a stand with American elm and shagbark hickory. The roosting home range used by any single Indiana bat was as large as 568 hectares in an oak-pine community in Kentucky.[22] Roosts of two maternity colonies in southern Illinois were located in roosting areas estimated at 11.72 hectares and 146.5 hectares, and included green ash, American elm, silver maple, pin oak, and shagbark hickory.[17] The extent of the maternity home range may depend on the availability of suitable roosts in the area.[39]

Most habitat attributes measured for the Indiana bat were insignificant and inconsistent from one location to another. In Missouri, oak-hickory stands with maternity colonies had significantly more medium trees (12–22 in or 30–57 cm dbh) and significantly more large-sized trees (>22 inches or 57 cm dbh) than areas where Indiana bats were not found. No other major landscape differences were detected.[31]

Distances seen between roosts and other habitat features may be influenced by the age, sex, and reproductive condition of these bats. Distances between roosts and paved roads is greater than the distances between roosts and unpaved roads in some locales, although overlap between the two situations has been documented. In Illinois, most roosts used by adult females and juveniles were about 2,300 feet (700 m) or more from a paved highway, while adult males roosted less than 790 feet (240 m) from the road.[14][18] In Michigan, roosts were only slightly closer to paved roads: 2,000 feet (610 m) on average for all roosts located.[23] In general, roosts were located 1,600 to 2,600 feet (490 to 790 m) from unpaved roads in Illinois and Michigan.[18][23] Roost trees used during autumn in Kentucky were very close to unpaved roads at an average of 160 feet (49 m).[21]

Roost proximity to water is highly variable, so probably not as important as once thought. In Indiana, roost trees were discovered less than 660 feet (200 m) from a creek,[20] while roosts in another part of Indiana were 1.2 miles (1.9 km) from the nearest permanent water source.[18][23] To the other extreme, roosts of a maternity colony from Michigan were all found in a 12-acre (5 ha) wetland that was inundated for most of the year.[23] In Virginia, foraging areas near a stream were used.[38] Intermittent streams may be located closer to roosts than more permanent sources of water.[14][23] Ponds, streams, and road ruts appear to be important water sources, especially in upland habitats.[40]

Foraging habitat

Studies on the foraging needs for Indiana bats are inconclusive. Bats forage[16] in a landscape composed of pasture, corn fields, woodlots, and a strip of riparian woodland, although Indiana bat activity was not necessarily recorded in all these habitat types. Murray and Kurta[32] made some qualitative assessments of Indiana bat foraging habitat in Michigan; the majority of bats was found foraging in forested wetlands and other woodlands, while one bat foraged in an area around a small lake and another in an area with 50% woodland and 50% open fields. Another Indiana bat foraged over a river, while 10 others foraged in areas greater than 0.6 miles (0.97 km) from the same river.[32]

Bat activity was centered around small canopy gaps or closed forest canopy along small second-order streams in West Virginia. Indiana bats foraged under the dense oak-hickory forest canopy along ridges and hillsides in eastern Missouri, but rarely over streams.[41] Indiana bats have been detected foraging in upland forest [15][21][26] in addition to riparian areas such as floodplain forest edges.[15][20][26][42] Romme and others [37] also suggested that foraging habitat would ideally have 50% to 70% canopy closure. Indiana bats rarely use open agricultural fields and pastures, upland hedgerows, open water, and deforested creeks for traveling or foraging.[18][20][32]

Hibernacula

During hibernation, Indiana bats occupy open areas of hibernacula ceilings and generally avoid crevices and other enclosed areas.[43] They were associated with hibernacula that were long (µ=2,817 feet or 858 m), had high ceilings (µ=15 feet or 4.5 m), and had large entrances (µ=104.4 feet² or 9.7 m2). The preferred hibernacula often had multiple entrances promoting airflow. Hibernacula choice may be influenced by the ability of the outside landscape to provide adequate forage upon arrival at the hibernacula, as well as the specific microclimate inside. Having forested areas around the hibernacula entrance and low amounts of open farmland may be important factors influencing the suitability of hibernacula.[43]

Cover requirements

Primary roosts used by Indiana bats are typically snags in canopy gaps and forest edges that receive direct sunlight throughout the day.[16] Alternate roosts are live or dead trees, generally located in the forest interior, that usually receive little or no direct sunlight.[16][20] Weather, such as very warm temperatures and precipitation, appears to influence the use of interior alternate roost trees over primary roosts, as alternate roosts generally offer more shade and protection during inclement weather and extreme heat.[16][20][31] However, this preference may fluctuate from season to season. Indiana bats moved to the alternate roost during periods of heavy rain and colder ambient temperatures during fall in Missouri, but chose to roost in the primary snag during inclement weather in the spring. These differences may be attributed to variation in the heat-retention capabilities of the trees at different times of the year.[20] Bats from a maternity colony switched roosts more frequently in summer and autumn than they did in spring in an oak-pine forest in Kentucky.[19] They exhibit strong fidelity to individual roost trees from year to year if they are still suitable roost sites.[19][20][44] Many trees are no longer usable after just a few years,[14][16][20][23][26][44] while others may last as long as 20 years.[28]

Another important factor relating to roost suitability is tree condition. Indiana bats prefer dead or dying trees with exfoliating bark.[23] The amount of exfoliating bark present on a tree seems to be insignificant.[21] Indiana bats show an affinity for very large trees that receive plentiful sunlight. Typically, Indiana bats roost in snags, but a few species of live trees are also used. Live roost trees are usually shagbark hickory, silver maple, and white oak.[14][16] Shagbark hickories make excellent alternate roosts throughout the Indiana bats' range due to their naturally exfoliating bark.[26] Although Indiana bats primarily roost under loose bark, a small fraction roosts in tree cavities.[14][23][24][30]

Primary roosts are generally larger than alternate roosts,[24] but both show variability. Females typically use large roost trees averaging 10.8 to 25.7 inches (27 to 65 centimetres) as maternity roosts.[14][16][21][23][25][38][45] Males are more flexible, roosting in trees as small as 3 inches (7.6 cm) dbh.[14][21][22][38] In a review, Indiana bats required tree roosts greater than 8 inches (20 cm) dbh,[37] while roosts of 12 inches (30 cm) dbh or larger were preferred.[44] The heights of roost trees vary, but they tend to be tall, with average heights ranging from 62.7 to 100 feet (19.1 to 30.5 m). The heights of the actual roosting sites are variable, as well, ranging from 4.6 to 59 feet (1.4 to 18.0 m).[23][25][38]

In addition to day roosts, Indiana bats use temporary roosts throughout the night to rest between foraging bouts. Limited research has examined the use of night roosts by Indiana bats, thus their use and importance are poorly understood. Males, lactating and postlactating females, and juveniles have been found roosting under bridges at night. Some Indiana bats were tracked to three different night roosts within the same night.[32] Night roosts are often found within the bats' foraging area. Indiana bats using night roosts are thought to roost alone and only and for short periods, typically 10 minutes or less. Lactating bats may return to the day roost several times each night, presumably to nurse their young. Pregnant bats have not been tracked back to the day roost during the night except during heavy rain. Because Indiana bats are difficult to track during their nightly movements and usually rest for such short periods of time, the specific requirements that Indiana bats need in a night roost, and reasons why night roosts are needed, are still unknown.

During spring and fall, Indiana bats migrate between hibernacula and summer roosting sites. In New York and Vermont, bats traveled up to 25 miles (40 km) between hibernacula and summer roosting sites in spring. This is a considerably shorter distance than what is seen in the Midwest, where bats may travel up to 300 miles (480 km). Many males remain close to hibernacula during the spring and summer[36] rather than migrating long distances like females. Occasionally, they even roost within hibernacula during the summer.[36] Males also roost in caves and trees during fall swarming.[36][44] Few data exist for the roosting requirements of Indiana bats during spring and fall migrations; data indicate that requirements during these times are similar to summer needs in that the bats chose large trees with direct sunlight and exfoliating bark.[38]

The ability for Indiana bats to find suitable hibernating conditions is critical for their survival. A hibernaculum that remained too warm during one winter caused a 45% mortality rate in hibernating bats.[46] They generally hibernate in warmer portions of the hibernacula in fall, then move to cooler areas as winter progresses. During October and November, temperatures at roosting sites within major hibernacula in six states averaged 43.5 to 53.2 °F (6.4 to 11.8 °C). Roost temperatures at the same hibernacula ranged from 34.5 to 48.6 °F (1.4 to 9.2 °C) from December to February. Temperatures in March and April were slightly lower than in autumn at 39.6 to 51.3 °F (4.2 to 10.7 °C). Indiana bat populations increased over time in hibernacula that had stable midwinter temperatures averaging 37.4 to 45.0 °F (3.0 to 7.2 °C), and declined in hibernacula with temperatures outside this range.[26]

Temperatures slightly above freezing during hibernation allow Indiana bats to slow their metabolic rates as much as possible without the risk of freezing to death or using up fat too quickly.[46] Hibernating bats may also survive low temperatures by sharing body heat within the tight clusters they typically form.[33] Bats awaken periodically throughout the hibernation period, presumably to eliminate waste or to move to more appropriate microclimates. This periodic waking does not seem to affect their survival, but waking caused by disturbance can cause Indiana bats to use up large amounts of energy, which can cause them to run out of fat reserves before the end of winter, possibly leading to death.[47]

One way in which caves retain low temperatures is through a constant input of cold air from outside the cave. Typically, the caves supporting the largest populations have multiple entrances that allow cool air from outside the cave to come in, creating a circulation of fresh, cooled air. Gates that are meant to keep vandals out of caves have altered the temperature and airflow of hibernacula, resulting in population declines of Indiana bats at many major hibernacula throughout their range. Removing or modifying gates at some of these have given these populations a chance to rebound. Also, the bats seem to prefer a relative humidity of 74 to 100%, although the air is not commonly saturated.[44] Relative humidities of only 50.4% have also been recorded.[43]

Food habits

Indiana bats feed exclusively on terrestrial and aquatic flying insects.[42] The most common prey items taken are moths (Lepidoptera), beetles (Coleoptera), and mosquitoes and midges (Diptera).[27] Selection of prey depends largely on availability in the foraging habitat with diet varying seasonally, by reproductive status of females, and from night to night. In southern Michigan, Indiana bats primarily ate caddisflies (Trichoptera) and bees, wasps, and ants (Hymenoptera), in addition to the more common prey previously listed.[42] In the Ozarks of southern Missouri, the bats also primarily ate bees, wasps, ants, moths, and beetles, as well as leafhoppers (Homoptera), although diet did vary throughout the summer. Bats in Indiana were found to prefer beetles, moths, mosquitoes, midges, leafhoppers, and wasps.[48] Other arthropod groups which are consumed by Indiana bats in very limited quantities are lacewings (Neuroptera), spiders (Araneae), stoneflies (Plecoptera), mayflies (Ephemeroptera), mites and ticks (Acari), and lice (Phthiraptera).[21][42]

In addition to differences in diet, variation in foraging behaviors have been documented. For instance, the distance that an individual Indiana bat travels between a day roost and a nightly foraging range can vary. Indiana bats traveled up to 1.6 miles (2.6 km) from their day roosts to their foraging sites in Illinois.[18] Similarly, bats traveled up to 1.5 miles (2.4 km) to forage in Kentucky.[21] In Michigan, female bats traveled as far as 2.6 miles (4.2 km) to reach foraging areas with an average of 1.5 miles (2.4 km).[32]

Several studies have documented similarities in how foraging habitats are actually used by Indiana bats. Indiana bats in Indiana were foraging around the canopy, which was 7 to 98 feet (2.1 to 29.9 m) above ground.[20] In Missouri, a female bat foraged 7 to 33 feet (2.1 to 10.1 m) above a river.[41] A male Indiana bat was observed flying in an elliptical pattern among trees at 10 to 33 feet (3.0 to 10.1 m) above the ground under the canopy of dense forests.[41] In addition, bats were foraging at canopy height in Virginia.[38]

Differences in the extent of foraging ranges have also been noted. Bats from the same colony foraged in different areas at least some of the time.[32] The average foraging area for female bats in Indiana was 843 acres (341 hectares), but the foraging area for males averaged 6,837 acres (2,767 hectares).[20] A male bat used a foraging area of 1,544 acres (625 hectares) in Virginia.[38] In Illinois, however, the foraging ranges were much smaller at an average of 625 acres (253 hectares) for adult females, 141 acres (57 hectares) for adult males, 91 acres (37 hectares) for juvenile females, and only 69 acres (28 hectares) for juvenile males.[14][18][21] Foraging areas used by Indiana bats in Indiana increased throughout the summer season, but only averaged 11.2 acres (4.5 hectares) in midsummer.[20]

Predators

During hibernation, predators of Indiana bats may include black rat snakes (Pantherophis obsoletus) [49] and northern raccoons (Procyon lotor).[45][49] During other times of the year, northern raccoons have been observed trying to grab bats from the air when they attempt to fly away.[45] Skunks (Mephitidae), Virginia opossums (Didelphis virginiana), and feral cats (Felis catus) may pose a similar threat.[49] If Indiana bats fly from their day roosts during the day, they may be susceptible to predation by hawks (Accipitridae).[45][49] Indiana bats foraging at night may also be susceptible to predation by owls (Strigidae).[20][49] While not a predator, woodpeckers (Picidae) may disturb roosting bats through their foraging activities by peeling away sections of bark being used by Indiana bats, causing them to fly from the roost during the day and making the tree unsuitable for future habitation.[23][45]

The impact of natural predators on Indiana bats is minimal compared to the damage to habitat and mortality caused by humans, especially during hibernation. The presence of people in caves can cause Indiana bats to come out of hibernation, leading to a large increase in their energy use. By causing them to wake up and use greater amounts of energy stores, humans can cause high mortality in a cave population of hibernating Indiana bats.[47] Human disturbance and the degradation of habitat are the primary causes for their decline.[50]

In popular culture

In the year 2020, the American "field recorder" Stuart Hyatt released a music album which combines sounds made by the Indiana bat along with music from ambient and experimental artists. Hyatt recorded the ultrasonic echolocations of the Indiana bat and then modulated the sounds in order to make the sounds audible to humans. This "sound library" of the Indiana bat was sent to musicians who then combined the sounds from the Indiana bat along with original music. Hyatt was quoted as saying that "bat noises are like bird songs, just in a register no one can hear. I wanted to bring out the musicality of their voices." Hyatt's album is entitled Ultrasonic, and it features music from "Eluvium," "Machinefabriek," Ben Lukas Boysen and others.[51][52] The album also features a poem written and read by the poet Cecily Parks about the Indiana bat.[53][54]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Ospina-Garces, S. (2016). "Myotis sodalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T14136A22053184. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T14136A22053184.en. https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/14136/22053184. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ↑ "Annual Report 2013-2014". Bat Conservation International. August 2014. http://www.batcon.org/images/stories/annualreports/AnnualReport2014.pdf.

- ↑ Turner G.G.; Reeder, D.M.; Coleman, J.T.H. (2011). "A five-year assessment of mortality and geographic spread of white-nose syndrome in North American bats, with a look at the future". Bat Research News 52: 13–27. https://reviverestore.org/wp-content/uploads/user-publications/turner-et-al-2011-brn-wns.pdf.

- ↑ Reeder, DeeAnn M.; Frank, Craig L.; Turner, Gregory G.; Meteyer, Carol U.; Kurta, Allen; Britzke, Eric R.; Vodzak, Megan E.; Darling, Scott R. et al. (2012-06-20). "Frequent Arousal from Hibernation Linked to Severity of Infection and Mortality in Bats with White-Nose Syndrome". PLOS ONE 7 (6): e38920. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038920. PMID 22745688. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...738920R.

- ↑ "Unexplained "White Nose" Disease Killing Northeast Bats". Environment News Service. 2008-01-31. http://www.ens-newswire.com/ens/jan2008/2008-01-31-094.asp.

- ↑ "Kentucky Residents Sentenced After Pleading Guilty to Killing Endangered Bats". United States: Fish and Wildlife Service. 18 March 2010. http://www.fws.gov/southeast/news/2010/r10-019.html.

- ↑ "BATS Magazine Archive". http://batcon.org/index.php/media-and-info/bats-archives.html?task=viewArticle&magArticleID=1049.

- ↑ Woody, Todd (10 December 2009). "Judge Halts Wind Farm Over Bats". The New York Times. http://green.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/12/10/judge-halts-wind-farm-over-bats/.

- ↑ Good, R. E., W. Erickson, A. Merrill, S. Simon, K. Murray, K. Bay, and C. Fritchman. (2011). Bat monitoring studies at the fowler ridge wind energy facility in Benton County, Indiana. WEST, Incorporated

- ↑ "Pruitt, L. and J. Okajima. 2013. Indiana Bat Fatalities at Wind Energy Facilities. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bloomington, Indiana.". United States. July 2013. http://www.fws.gov/midwest/wind/wildlifeimpacts/pdf/IndianaBatFatalitiesSummaryJuly2013.pdf.

- ↑ Fiedler, J. K., H. Henry, R.D. Tankersley, and C.P. Nicholson. (2007). Results of bat and bird mortality at the expanded buffalo mountain wind farm, 2005. Final report prepared for Tennessee Valley Authority.

- ↑ Cryan, P.M. and R.M.R. Barclay. 2009. Causes of Bat Fatalities at Wind Turbines; Hypotheses and Predictions. 90 (6):1330-1340. Cryan, Paul M.; Barclay, Robert M. R. (2009). "Causes of Bat Fatalities at Wind Turbines: Hypotheses and Predictions". Journal of Mammalogy 90 (6): 1330–1340. doi:10.1644/09-MAMM-S-076R1.1.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Clawson, Richard L. "Trends in population size and current status", pp. 2-8 in Kurta

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 14.11 14.12 14.13 14.14 Gardner, James E.; Garner, James D.; Hofmann, Joyce E. (1991). Summer roost selection and roosting behavior of Myotis sodalis (Indiana bat) in Illinois. Final report. Champaign, IL: Illinois Department of Conservation, Illinois Natural History Survey. On file with: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station, Fire Sciences Laboratory, Missoula, MT

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Clark, Bryon K.; Bowles, John B.; Clark, Brenda S. (1987). "Summer status of the endangered Indiana bat in Iowa". The American Midland Naturalist 118 (1): 32–39. doi:10.2307/2425625.

- ↑ 16.00 16.01 16.02 16.03 16.04 16.05 16.06 16.07 16.08 16.09 16.10 16.11 16.12 Callahan, Edward V.; Drobney, Ronald D.; Clawson, Richard L. (1997). "Selection of summer roosting sites by Indiana bats (Myotis sodalis) in Missouri". Journal of Mammalogy 78 (3): 818–825. doi:10.2307/1382939.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Carter, Timothy C.; Carroll, Steven K.; Feldhamer, George A. (2001). "Preliminary work on maternity colonies of Indiana bats in Illinois". Bat Research News 42 (2): 28–29.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Garner, James D.; Gardner, James E. (1992). Determination of summer distribution and habitat utilization of the Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) in Illinois. Illinois Department of Conservation, Illinois Natural History Survey. Final Report: Project E-3

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Gumbert, Mark W.; O'Keefe, Joy M.; MacGregor, John R. "Roost fidelity in Kentucky", pp. 143-152 in Kurta

- ↑ 20.00 20.01 20.02 20.03 20.04 20.05 20.06 20.07 20.08 20.09 20.10 20.11 20.12 20.13 20.14 20.15 20.16 20.17 20.18 Humphrey, Stephen R.; Richter, Andreas R.; Cope, James B. (1977). "Summer habitat and ecology of the endangered Indiana bat, Myotis sodalis". Journal of Mammalogy 58 (3): 334–346. doi:10.2307/1379332.

- ↑ 21.00 21.01 21.02 21.03 21.04 21.05 21.06 21.07 21.08 21.09 21.10 21.11 21.12 Kiser, James D.; Elliott, Charles L. 1996. Foraging habitat, food habits, and roost tree characteristics of the Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) during autumn in Jackson County, Kentucky. Frankfort, KY: Kentucky Department of Fish and Wildlife Resources

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 22.4 MacGregor, John R.; Kiser, James D.; Gumbert, Mark W.; Reed, Timothy O. 1999. Autumn roosting habitat of male Indiana bats (Myotis sodalis) in a managed forest setting in Kentucky. In: Stringer, Jeffrey W.; Loftis, David L., eds. "Proceedings, 12th central hardwood forest conference; 1999 February 28 – March 2"; Lexington, KY. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-24. Asheville, NC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station.: 169–170

- ↑ 23.00 23.01 23.02 23.03 23.04 23.05 23.06 23.07 23.08 23.09 23.10 23.11 Kurta, Allen; King, David; Teramino, Joseph A.; Stribley, John M.; Williams, Kimberly J. (1993). "Summer roosts of the endangered Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) on the northern edge of its range". The American Midland Naturalist 129 (1): 132–138. doi:10.2307/2426441.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 Britzke, Eric R.; Harvey, Michael J.; Loeb, Susan C. (2003). "Indiana bat, Myotis sodalis, maternity roosts in the southern United States". Southeastern Naturalist 2 (2): 235–242. doi:10.1656/1528-7092(2003)002[0235:IBMSMR2.0.CO;2]. http://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/viewpub.php?index=5477.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 25.6 Stone, William E.; Battle, Ben L. (2004). "Indiana bat habitat attributes at three spatial scales in northern Alabama". Bat Research News 45 (2): 71.

- ↑ 26.00 26.01 26.02 26.03 26.04 26.05 26.06 26.07 26.08 26.09 26.10 26.11 26.12 26.13 26.14 26.15 26.16 26.17 26.18 26.19 U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. (1999). Agency draft: Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis) revised recovery plan. Fort Snelling, MN: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Region 3

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 LaVal, Richard K.; LaVal, Margaret L. (1980). Ecological studies and management of Missouri bats. Terrestrial Series #8. Jefferson City, MO: Missouri Department of Conservation

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 28.6 Schultz, John R. 2003. Appendix C – Biological Assessment. In: Prescribed Fire Environmental Assessment. Bradford, PA: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Allegheny National Forest

- ↑ Paradiso, John L.; Greenhall, Arthur M. (1967). "Longevity records for American bats". The American Midland Naturalist 78 (1): 251–252. doi:10.2307/2423387.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 Kurta, Allen; Murray, Susan W.; Miller, David H. "Roost selection and movements across the summer landscape", pp. 118-129 in Kurta

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 31.5 Miller, Nancy E.; Drobney, Ronald D.; Clawson, Richard L.; Callahan, E. V. "Summer habitat in northern Missouri", pp. 165-171 in Kurta

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 Murray, S. W.; Kurta, A. (2004). "Nocturnal activity of the endangered Indiana bat (Myotis sodalis)". Journal of Zoology 262 (2): 197. doi:10.1017/S0952836903004503.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Clawson, Richard L.; LaVal, Richard K.; LaVal, Margaret L.; Caire, William (1980). "Clustering behavior of hibernating Myotis sodalis in Missouri". Journal of Mammalogy 61 (2): 245–253. doi:10.2307/1380045. http://www.fort.usgs.gov/BPD/BPD_bib_viewObs.asp?BibID=123.

- ↑ U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service (1976). "Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants: Determination of critical habitat for American crocodile, California condor, Indiana bat, and Florida manatee". Federal Register 41 (187): 41914–41916. http://ecos.fws.gov/speciesProfile/profile/speciesProfile.action?spcode=A000.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Salyers, Jo; Tyrell, Karen; Brack, Virgil (1996). "Artificial roost structure use by Indiana bats in wooded areas in central Indiana". Bat Research News 37 (4): 148.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 Widlak, James C. (1997). Biological opinion on the impacts of forest management and other activities to the Indiana bat on the Cherokee National Forest, Tennessee. Cookeville, TN: U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Romme, Russell C.; Tyrell, Karen; Brack, Virgil, Jr. (1995). Literature summary and habitat suitability index model: components of summer habitat for the Indiana bat, Myotis sodalis. Project C7188: Federal Aid Project E-1-7, Study No. 8. Bloomington, IN: Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Fish and Wildlife

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 38.6 38.7 Hobson, Christopher S.; Holland, J. Nathaniel (1995). "Post-hibernation movement and foraging habitat of a male Indiana bat, Myotis sodalis (Chiroptera: Vespertilionidae), in western Virginia". Brimleyana 23: 95–101.

- ↑ U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service. (1999). Biological opinion on the impacts of forest management and other activities to the bald eagle, Indiana bat, clubshell, and northern riffleshell on the Allegheny National Forest.

- ↑ Martin, Chester O.; Kiser James D. (2004). "Managing special landscape features for forest bats, with emphasis on riparian areas and water sources". Bat Research News 45 (2): 62–63.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 LaVal, Richard K.; Clawson, Richard L.; LaVal, Margaret L.; Caire, William (1977). "Foraging behavior and nocturnal activity patterns of Missouri bats, with emphasis on the endangered species Myotis grisescens and Myotis sodalis". Journal of Mammalogy 58 (4): 592–599. doi:10.2307/1380007.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 Murray, Susan W.; Kurta, Allen "Spatial and temporal variation in diet", pp. 182-192 in Kurta

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Raesly, Richard L.; Gates, J. Edward (1987). "Winter habitat selection by north temperate cave bats". The American Midland Naturalist 118 (1): 15–31. doi:10.2307/2425624.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 Clawson, Richard L. 2000. Implementation of a recovery plan for the endangered Indiana bat. In: Vories, Kimery C.; Throgmorton, Dianne, eds. In: Proceedings of bat conservation and mining: a technical interactive forum; 2000 November 14–16; St. Louis, MO. Alton, IL: U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Surface Mining; Carbondale, IL: Coal Research Center, Southern Illinois University: 173–186

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 45.3 45.4 Sparks, Dale W.; Simmons, Michael T.; Gummer, Curtis L.; Duchamp, Joseph E. (2003). "Disturbance of roosting bats by woodpeckers and raccoons". Northeastern Naturalist 10 (1): 105–108. doi:10.1656/1092-6194(2003)010[0105:DORBBW2.0.CO;2].

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Richter, Andreas R.; Humphrey, Stephen R.; Cope, James B.; Brack, Virgil Jr. (1993). "Modified cave entrances: thermal effect on body mass and resulting decline of endangered Indiana bats (Myotis sodalis)". Conservation Biology 7 (2): 407–415. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1993.07020407.x.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Thomas, Donald W. (1995). "Hibernating bats are sensitive to nontactile human disturbance". Journal of Mammalogy 76 (3): 940–946. doi:10.2307/1382764.

- ↑ Whitaker, John O. (2004). "Prey Selection in a Temperate Zone Insectivorous Bat Community". Journal of Mammalogy 85 (3): 460–469. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2004)085<0460:PSIATZ>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 1545-1542.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 Warwick, Adam; Fredrickson, Leigh H.; Heitmeyer, Mickey (2001). "Distribution of bats in fragmented wetland forests of southeast Missouri". Bat Research News 42 (4): 187.

- ↑ Brady, John T. (1983). "Use of dead trees by the endangered Indiana bat". In: Davis, Jerry W.; Goodwin, Gregory A.; Ockenfeis, Richard A., technical coordinators. Snag habitat management: proceedings of the symposium; 1983 June 7–9; Flagstaff, AZ. Gen. Tech. Rep. RM-99. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 111–113

- ↑ Currin, Grayson Haver (10 June 2020). "Vilified for Virus, Bats are a New Album's Seductive Stars". The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/10/arts/music/bats-field-works-ultrasonic.html.

- ↑ Simpson, Paul. "Field Works: Ultrasonic". AllMusic. https://www.allmusic.com/album/ultrasonic-mw0003358271.

- ↑ Parks, Cecily. "The Indiana Bats". Orion Magazine. https://orionmagazine.org/poetry/the-indiana-bats/.

- ↑ Carroll, Tobias (1 May 2020). "Stuart Hyatt on Turning Bat Sounds into Stunning Ambient Music". Vol.1 Brooklyn. http://vol1brooklyn.com/2020/05/01/stuart-hyatt-on-turning-bat-sounds-into-amazing-music/.

Cited sources

- The Indiana bat: biology and management of an endangered species. Austin, TX: Bat Conservation International. 2002. https://www.merlintuttle.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Thermal_Requirements_During_Hibernation_2002.pdf.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Indiana Department of Natural Resources, Division of Fish and Wildlife: Indiana Bats

- Ohio Department of Natural Resources Life History Notes: Indiana Bat Myotis sodalis

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service: Indiana Bat, Myotis sodalis

- National Wildlife Federation: Indiana Bat

- Species Profile: Indiana Bat U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

- U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service: Indiana bat images

- Capture and release of Indiana bats

Wikidata ☰ Q281343 entry