Biology:The Goldfinch (painting)

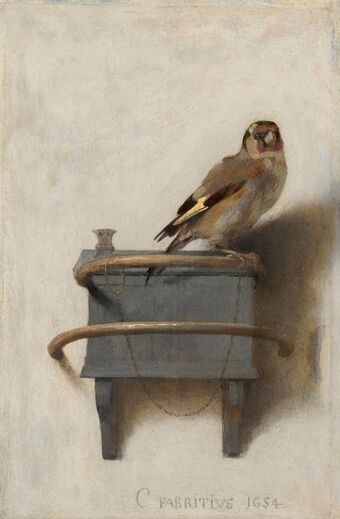

| The Goldfinch | |

|---|---|

| Dutch: Het puttertje | |

| |

| Artist | Carel Fabritius |

| Year | 1654 |

| Type | Bird painting |

| Medium | Oil on panel |

| Subject | European goldfinch |

| Dimensions | 33.5 cm × 22.8 cm (13.2 in × 9.0 in) |

| Location | Mauritshuis, The Hague, Netherlands |

| Accession | 1896 |

The Goldfinch (Dutch: Het puttertje) is a 1654 bird painting by Dutch artist Carel Fabritius of a life-size chained goldfinch that is now in the collection of the Mauritshuis in The Hague, Netherlands. It is a trompe-l'œil oil on a 33.5 by 22.8 centimetres (13.2 in × 9.0 in) panel that was once part of a larger structure, perhaps a window jamb or a protective cover. It is possible that the painting was in its creator's workshop in Delft at the time of the gunpowder explosion that killed him.

A common and colourful bird with a pleasant song, the goldfinch was a popular pet, and it could be taught simple tricks including lifting a thimble-sized bucket of water. It was reputedly a bringer of good health, and it was a popular subject for Renaissance painters as a symbol of Christian redemption and the Passion of Jesus.

The painting is unusual for the Flemish Baroque period in the simplicity of its composition and use of illusionary techniques. Following the death of its creator, it was lost for more than two centuries before its rediscovery in Brussels. This artwork plays a central role in the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt and its film adaptation.

Subject

The painting shows a life-size European goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) on top of its feeder, a blue container with a lid, that is enclosed by two metal half-rings fixed to the wall. The bird is perched on the upper ring, to which its leg is attached by a fine chain.[1] The painting is signed "C fabritivs 1654" at the bottom.[2]

The goldfinch is a widespread and common seed-eating bird in Europe, North Africa, and western and central Asia.[3] As a colourful species with a pleasant twittering song, and an associated belief that it brought health and good fortune,[4] It has been domesticated for at least 2000 years.[5] Pliny recorded that it could be taught to do tricks,[5] and in the 17th century, it became fashionable to train goldfinches to draw water from a bowl with a miniature bucket on a chain. The Dutch title of the painting is the bird's nickname puttertje, which refers to this custom and is equivalent to "draw-water", an old Norfolk name for the bird.[4] This behaviour is shown in Fruit Still-Life with Squirrel and Goldfinch by Abraham Mignon.

The goldfinch is a popular topic for painters, not just for its colourful appearance but also for its symbolic meanings. Pliny associated the bird with fertility, and the presence of a giant goldfinch next to a naked couple in The Garden of Earthly Delights triptych by the earlier Dutch master Hieronymus Bosch perhaps refers to this belief.[4]

Nearly 500 Renaissance religious paintings, mainly by Italian artists, show the bird,[6][lower-alpha 1] In Medieval Christianity, the goldfinch's association with health symbolises the Redemption, and its habit of feeding on the seeds of spiky thistles, together with its red face, presaged the crucifixion of Jesus, where the bird supposedly became splattered with blood while attempting to remove the crown of thorns.[5][8] Many of these devotional paintings were created in the second quarter of the fourteenth century while the Black Death pandemic gripped Europe.[6]

Physical characteristics

The Goldfinch is a 33.5 by 22.8 centimetres (13.2 in × 9.0 in) oil painting on panel in the collection of the Mauritshuis in The Hague, Netherlands.[2] Details of its physical structure emerged when it was restored in 2003.[9]

The panel on which it is painted is 8–10 millimetres (0.31–0.39 in) thick, which is atypically deep for a small painting, and indicates that it may have formerly been part of a larger piece of wood. Evidence for this is the remains of a wooden pin, suggesting that the original boards had been joined with dowels and glue. Before it was framed, the painting had a 2 centimetres (0.79 in) black border onto which a gilded frame was later fixed with ten equally spaced nails. The nails did not reach the back of the panel so there is no evidence of a backing to the picture. The frame was subsequently removed leaving only a residual line of a greenish copper compound. Fabritius then extended the white background pigment to the right edge, repainted his signature, and added the lower perch. Finally, the remaining black edges were over-painted with white.[9]

The back of the panel has four nail holes and six other holes near the top, suggesting two different methods of suspension of the panel at various times. American art historian Linda Stone-Ferrier has suggested that the panel may have been either attached to the inner jamb of a window or have been a hinged protective cover for another wall-mounted painting.[9]

During conservation, it was realised that the surface of the painting had numerous small dents that must have been formed when the paint was still not fully dried, since there was no cracking. It is possible that the slight damage was caused by the explosion that killed its creator.[10]

Style

The Goldfinch is a trompe-l'œil painting which uses artistic techniques to create the illusion of depth, notably through foreshortening of the head, but also by highlights on the rings and the bird's foot, and strong shadows on the plastered wall.[11] The viewpoint seems to be from slightly below the bird, suggesting that it was intended to be mounted in an elevated position. Stone-Ferrier's supposition that it may at one time have been part of a window jamb relies in part on the painting giving the illusion of a real perched bird to passers-by, which is consistent with a raised location.[9]

Although other artists of the time, including Fabritius' master Rembrandt, used trompe-l'œil, the simplicity of the design of this work combined with the perspective technique are unique for paintings of the Flemish Baroque period,[9][11] and the simple depiction of a single bird is a minimalist version of the style.[11]

German-Dutch art historian Wilhelm Martin considered that The Goldfinch could only be compared with the Still-Life with Partridge and Gauntlets painted by Jacopo de' Barbari in 1504, more than 100 years earlier. The bird itself was created with broad brush strokes, with only minor later corrections to its outline, while details, including the chain, are added with more precision.[11] Fabritius' style differs from Rembrandt's typical chiaroscuro in his use of cool daylight, complex perspective,[12] and dark figures against a light background.[13]

Carel Fabritius

Fabritius was born in 1622, as Carel Pietersz, in Middenbeemster in the Dutch Republic. Initially he worked as a carpenter (Latin: fabritius), and although not formally trained in art, his father and his brothers Barent and Johannes were painters, and his ability gained him a place at Rembrandt's studio in Amsterdam.[14] In the early 1650s he moved to Delft, and joined the St Luke painters' guild in 1652.[11]

Fabritius died young, caught in the explosion of the Delft gunpowder magazine on October 12, 1654, which destroyed a quarter of the city,[15] along with his studio and many of his paintings. Few of his works are known to have survived.[16] According to his contemporary Arnold Houbraken, Fabritius' student, Mattias Spoors, and church deacon Simon Decker died with him, since the three were working together on a painting at the time.[16] The Goldfinch was painted in the year that Fabritius died.[5]

Fabritius' works were well regarded by his contemporaries,[9] and his style influenced other notable Dutch painters of the period, including Pieter de Hooch, Emanuel de Witte and Vermeer.[12]

Ownership

The previously unknown The Goldfinch first came to light in 1859 when French art critic Théophile Thoré-Bürger found it in the collection of former Dutch army officer and collector Chevalier Joseph-Guillaume-Jean Camberlyn in Brussels. It was subsequently given to Thoré-Bürger by the chevalier's heirs in 1865, and he in turn bequeathed it with the rest of his collection to his companion, Apolline Lacroix, in 1869.[17][18][19][lower-alpha 2]

It was sold to Etienne Haro for 5,500 francs at the Hôtel Drouot in Paris on 5 December 1892, and later purchased for the Mauritshuis by its curator and art collector Abraham Bredius for 6,200 francs at the sale of the E. Martinet collection, also at Hôtel Drouot, on 27 February 1896. The painting is currently in the permanent collection of the Mauritshuis in The Hague.[2][18][21]

In popular culture

The Goldfinch plays a central role in the 2013 eponymous novel by American author Donna Tartt. The novel's protagonist, 13-year-old Theodore "Theo" Decker, survives a terrorist bombing at New York City Metropolitan Museum of Art in which his mother dies. He takes the Fabritius painting with him as he escapes the building, and much of the rest of the book is based around his attempts to hide the picture, its theft and eventual return.

The book won the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for fiction,[22] and was a commercial success with sales reaching nearly 1.5 million soon after the award.[23] The book's cover is itself a trompe l’oeil, with the painting visible through an illusionary tear in the paper. In reality, the painting has never been displayed in the Metropolitan Museum, although coincidentally an exhibition including The Goldfinch opened at New York's Frick Collection on the day of the novel's publication.[24][25] An estimated 200,000 people attended the Frick exhibition, despite freezing temperatures.[26]

Tartt's book was adapted as a 2019 film produced by Warner Bros and Amazon Studios,[27] directed by John Crowley,[28] and starring Ansel Elgort as Theo Decker.[29] The film was poorly received, with review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes giving an approval rating of 24%, and an average score of 4.5/10,[30] and Metacritic showing a weighted average score of 40 out of 100.[31] Following a poor opening, it was estimated it would lose as much as $50 million for the production companies.[32][33]

Other cultural references to The Goldfinch include American artist Helen Frankenthaler's 1960 abstract expressionist interpretation of the 1654 painting titled the Fabritius Bird,[34] and US poet Morri Creech's 2010 poem "Goldfinch", which includes the line "You stare/ from a modest trompe l’oeil heaven we don’t share".[35]

References

- ↑ "Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch, 1654". Mauritshuis. https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/explore/the-collection/artworks/the-goldfinch-605/#.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Details: Carel Fabritius, The Goldfinch, 1654". Mauritshuis. https://www.mauritshuis.nl/en/explore/the-collection/artworks/the-goldfinch-605/detailgegevens/.

- ↑ Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M, eds (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1561–1564. ISBN 978-0-19-854099-1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 448–451. ISBN 978-0-7011-6907-7.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Lederer, Roger J (2019). The Art of the Bird: The History of Ornithological Art Through Forty Artists. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 15, 21. ISBN 978-0-226-67505-3.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Friedmann, Herbert (1946). Symbolic Goldfinch: Its History and Significance in European Devotional Art. New York: Pantheon. pp. 6, 66.

- ↑ "The Goldfinch in Renaissance Art". BirdLife International. 2008. http://datazone.birdlife.org/sowb/casestudy/the-goldfinch-in-renaissance-art.

- ↑ Cocker, Mark (2013). Birds and People. London: Jonathan Cape. pp. 500–502. ISBN 978-0-224-08174-0.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 Stone-Ferrier, Linda (2016). "The Engagement of Carel Fabritius’ Goldfinch of 1654 with the Dutch Window, a Significant Site of Neighborhood Social Exchange". Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art 8 (1). doi:10.5092/jhna.2016.8.1.5. https://jhna.org/articles/engagement-carel-fabritius-goldfinch-1654-dutch-window-significant-site-neighborhood-social-exchange/.

- ↑ Noble, Petria; Mauritshuis (2009). Runia, Epco. ed. Preserving Our Heritage: Conservation, Restoration and Technical Research in the Mauritshuis. Wolle: Waanders. p. 154. ISBN 978-90-400-8621-2.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Martin, Wilhelm (1936). "De Hollandsche schilderkunst in de zeventiende eeuw: Rembrandt en zijn tijd" (in Dutch). Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren. http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/mart039holl02_01/mart039holl02_01_0006.php.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Montias, John Michael (1991). Vermeer and His Milieu: A Web of Social History (reprint, illustrated ed.). Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-691-00289-7.

- ↑ "Carel Fabritius". The National Gallery. https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/carel-fabritius.

- ↑ Brown, Christopher (1981). Carel Fabritius: Complete Edition with a catalogue raisonné. Oxford: Phaidon Press. pp. 15, 18. ISBN 0-7148-2032-6.

- ↑ Chambers, Chris (14 October 2004). "The Day the World Came to an End: the Great Delft Thunderclap of 1654". Radio Netherlands. https://www.radionetherlandsarchives.org/the-day-the-world-came-to-an-end-the-great-delft-thunderclap-of-1654/.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Houbraken, Arnold (1718). "De Groote Schouburgh der Nederlantsche Konstschilders en Schilderessen" (in Dutch). Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren. http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/houb005groo01_01/houb005groo01_01_0436.htm.

- ↑ "Chevalier Joseph Guillaume Jean Camberlyn (Biographical details)". British Museum. https://research.britishmuseum.org/research/search_the_collection_database/term_details.aspx?bioId=130265.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Jowell, Frances Suzman (2003). "Thoré-Bürger's Art Collection: "A Rather Unusual Gallery of Bric-à-Brac". Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 30 (1/2): 54 –119 (61, 68).

- ↑ Jowell, Frances Suzman (2001). "From Thoré to Bürger: The image of Dutch art before and after the Musées de la Hollande". Bulletin van het Rijksmuseum 49 (1): 43–60.

- ↑ Charreire, Magali, (2016). "Vermeer à l’Arsenal : la bibliothèque-musée de Paul Lacroix" (in French). Littératures 75: 45–56. doi:10.4000/litteratures.668. https://journals.openedition.org/litteratures/668#text.

- ↑ Schneider, Norbert (2003). Still life. Cologne: Taschen. p. 203. ISBN 978-3-8228-2081-0.

- ↑ "2014 Pulitzer winners in journalism and arts". Associated Press. 14 April 2014. https://apnews.com/3d9672326d77480188d22850c50839ac.

- ↑ "Tartt's 'Goldfinch' Doubles Sales Following Pulitzer Win". New York: PWxyz LLC. 24 April 2014. https://www.publishersweekly.com/pw/by-topic/industry-news/awards-and-prizes/article/61988-tartt-s-goldfinch-doubles-sales-following-pulitzer-win.html.

- ↑ Revely-Calder, Cal (29 September 2019). "The Goldfinch: how one little overlooked 17th-century painting became a global phenomenon". The Telegraph (London: Telegraph Media Group). https://www.telegraph.co.uk/art/what-to-see/goldfinch-one-little-overlooked-17th-century-painting-became/.

- ↑ "Vermeer, Rembrandt, and Hals: Masterpieces of Dutch Painting from the Mauritshuis: October 22, 2013 to January 19, 2014". Frick Collection. https://www.frick.org/exhibitions/past/2013/mauritshuis.

- ↑ "The Goldfinch". National Galleries Scotland. https://www.nationalgalleries.org/exhibition/goldfinch.

- ↑ "Amazon Studios, Warner Bros. Teaming on ‘The Goldfinch’ )". Variety (Variety Media). https://variety.com/2017/film/news/goldfinch-film-amazon-warner-bros-1202531064/. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ Fleming Jr., Mike (July 20, 2016). "‘Brooklyn’ Helmer John Crowley To Direct Donna Tartt’s Pulitzer Novel ‘Goldfinch’". Deadline Hollywood. http://deadline.com/2016/07/john-crowley-goldfinch-movie-brooklyn-donna-tartt-novel-warner-bros-1201789330/. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ Kroll, Justin (October 4, 2017). "Ansel Elgort Offered Lead Role in ‘Goldfinch’ Adaptation". Variety (Variety Media). https://variety.com/2017/film/news/ansel-elgort-goldfinch-adaptation-1202574604/. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ "The Goldfinch (2019)". https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/the_goldfinch/. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ "The Goldfinch reviews". https://www.metacritic.com/movie/the-goldfinch. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ Clark, Travis (January 13, 2020). "'The Goldfinch' is the biggest box-office flop of the year". https://www.businessinsider.com/the-goldfinch-is-biggest-box-office-bomb-of-the-year-2019-9. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ McClintock, Pamela (September 16, 2019). "'The Goldfinch' Bomb May Lose Up to $50M for Warner Bros., Amazon Studios". https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/box-office-bust-goldfinch-lose-40m-50m-warner-bros-amazon-1239816. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ↑ Schudel, Matt (6 April 2003). "Color Her World". Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale: Tribune Publishing). https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/fl-xpm-2003-04-06-0304040547-story.html.

- ↑ Creech, Morri (June 2010). "Goldfinch". First Things. https://www.firstthings.com/article/2010/06/goldfinch.

Notes

- ↑ Friedmann listed 486 paintings by 254 artists of whom 214 were Italian.[6] including da Vinci's Madonna Litta (1490–1491), Raphael's Madonna of the Goldfinch (1506) and Piero della Francesca's Nativity (1470).[7]

- ↑ Former actress Apolline Lacroix was the wife of his colleague Paul Lacroix, the curator of the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, and lived with Thoré-Bürger for more than a decade until his death.[20]

Selected bibliography

- Cornelis, Bart (1995). "A Reassessment of Arnold Houbraken's "Groote schouburgh"". Simiolus: Netherlands Quarterly for the History of Art 23 (2/3): 163–180. doi:10.2307/3780827.

- Davis, Deborah (2014). Fabritius and the Goldfinch. New York: Plympton. ISBN 978-1-68360-049-7.

- Tartt, Donna (2013). The Goldfinch. New York: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-1-4087-0495-0.

External links

- The Goldfinch at the Mauritshuis website.