Biology:Northern nail-tail wallaby

| Northern nail-tail wallaby | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Macropodidae |

| Genus: | Onychogalea |

| Species: | O. unguifera

|

| Binomial name | |

| Onychogalea unguifera (Gould, 1841)[2]

| |

| |

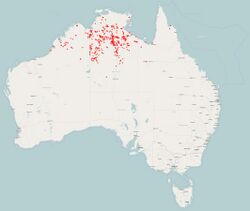

| The distribution of the northern nail-tail wallaby Data from The Atlas of Living Australia | |

The northern or sandy nail-tail wallaby (Onychogalea unguifera) is a species of macropod found across northern Australia on arid and sparsely wooded plains. The largest species of the genus Onychogalea, it is a solitary and nocturnal herbivorous browser that selects its food from a wide variety of grasses and succulent plant material. Distinguished by a slender and long-limbed form that resembles the typical and well known kangaroos, although their standing height is shorter, around half of one metre, and their weight is less than nine kilograms. As with some medium to large kangaroo species, such as Osphranter rufus, they have an unusual pentapedal motion at slow speeds by stiffening the tail for a fifth limb. When fleeing a disturbance, they hop rapidly with the tail curled back and repeatedly utter the sound "wuluhwuluh". Their exceptionally long tail has a broad fingernail-like protuberance beneath a dark crest of hair at its end, a peculiarity of the genus that is much broader than the other species. The name unguifera, meaning claw, is a reference to this extraordinary attribute, the purpose of which is unknown.

Like the other species of the genus, they retire for the day in a shallow depression, but if disturbed they flee rapidly to find refuge in a hollow tree or thicket. Unlike the rare bridled nail-tail wallaby (O. fraenata), once widespread and currently rare, the northern nail-tail wallaby is not a threatened species.[1] The other member of the genus Onychogalea, the crescent nail-tail wallaby (O. lunata) of the centre and west of Australia, probably became extinct in the mid-20th century.

Taxonomy

The first description and a specimen of Onychogalea unguifera was presented by John Gould to the Linnean Society of London in 1840, published in its journal the following year, and assigned to the genus Macropus. The epithet of the species was derived from the Latin term for "claw", a reference to the broad fingernail-like covering at the end of the tail that is a characteristic of the genus and most evident in this species.[2] Gould named this species and Onychogalea lunata when completing his second volume of Mammals of Australia around 1849, allying it to a genus established by George Waterhouse. A lithograph depicting several individuals included in Gould's books of mammals, executed by the painter Henry C. Richter, was first published in the author's monograph of the kangaroo family Macropodidae.[3] The single specimen examined by Gould was provided by Benjamin Bynoe, from a collection made at the northwestern coast of Australia during the expeditionary voyage of The Beagle.[4]

A common name, nail-tailed kangaroo, was provided by Gould for the peculiar claw at the tip of the tail, noting the presence of only a rudimentary spur in its relations.[4] The name in the Walpiri language is kururrungu,[5] and a word in Dalabon (Gunwinyguan, non-Pama-Nyungan) – wuluhwuluh – is derived from a sound that the species makes while hopping. An ethnobiological survey of Dalabon words for animals notes several onomatopoeic terms, but this is the only mammal named for its call; it is also locally referred to as the left-hand kangaroo.[6] The name karrabbal was reported by Knut Dahl, who recorded the species in Arnhem Land and made observations at Roebuck Bay.[7]

Two subspecies are generally recognised,[8][9]

- Onychogalea unguifera unguifera from the northwestern part of its range;

- Onychogalea unguifera annulicauda, first described by Charles Walter De Vis in 1884 as a new species, based on a single specimen of an immature female, collected by Kendall Broadbent during an expedition around the Norman River at the Gulf of Carpentaria.[10][11]

Description

The largest of a small group of macropods, the genus Onychogalea. known as nail-tail wallabies, which possess similar incisors and a dark growth resembling a fingernail or horny spur beneath a crest of fur at the end of the tail.[12] This claw-like feature of the tail is unique amongst the marsupials and an exceptional characteristic for any mammal, and this species bears the most prominent and developed tail nail of the genus.[4] Speculation on the purpose of the horny end includes its use as a defensive weapon, delivering a blow inflicted from the very long tail, or that it is an ancestral relic of a disused function.[7]

A hopping marsupial resembling the larger kangaroo species, the form of the body is light and elegant. The northern species is taller and heavier than other nailtails, but with limbs, tail and other features that are proportionally longer. They hop with their arms held in a stiff manner, so that these move in a circular motion, fleeing with their heads held low and long tail curled upward.[13][12] The curled posture of the tail, usual in macropods in motion, is exaggerated to nearly form a semi-circle.[7] The length of the head and body combined is 500 to 700 millimetres, exceeded by the tail measuring from 600 to 740 mm and an average length of 650 mm. The standing height of the animal, from the ground to the crown of the head, is around 0.65 metres, their weight ranges from five to nine kilograms. The colour of the pelage is a sandy colour, with gingery tones, becoming paler at the head and neck. A rufous shade is found at the flank, grading to the lighter creamy colour of the underside, and a creamy stripe breaks the greyish fur at the hip. The noted horny feature at the tail's terminus is hidden beneath a hairy blackish tuft, this darker coloration of the fur covers the last third of the tail. The upper body colour at the base of the tail fades to creamy white, sometimes merging with grey bands at the midpoint of the tail's length. The species have ears that are mobile, pale grey in colour, and exceptionally long at 80 to 92 mm.[13]

The utterance when fleeing an observer, described in the name wuluhwuluh, was noted by Knut Dahl as repeating a guttural sound "u-u-u".[7]

Behaviour

This marsupial is a nocturnal and usually solitary grazer and forager. The species is selective in its choice of the most palatable grasses or herbaceous and succulent plants, and is known to also consume some fruits.[1] They reside during the day beneath trees or shrubs in a shallow depression scraped into the sand. The species may seek to avoid discovery or seek refuge beneath a low shrubbery or by lying amongst some tall grass.[13]

The slow gait of O. unguifera has a characteristic usually associated with mid-sized to large species of Macropus and, like the pentapedal motion of the red kangaroo, uses all four limbs and the large tail to move forward in a "five-legged" manner. This form of locomotion has been attributed to variety of macropods, with contrary opinions on which actually use their large tails to pivot the hind legs forward, but video analysis of their movements confirms this species use of the unusual gait.[14]

A specimen captured in northern Queensland was successfully held in captivity, as a pet, at a Victorian garden in the early 20th century. The animal was friendly when active and recognised its custodian, who supplemented its forage with vegetation outside its enclosed area.[15]

Distribution and habitat

An endemic species of northern Australia that favours a diverse range of arid habitat and may be common at some locations in its broad distribution range. They occur in the northern parts of the continent, generally inland from the coastline, from the east at Cape York Peninsula, through the Top End and through the Kimberley region to the northwestern coast.[13] The areas occupied by Onychogalea unguifera are patchily distributed within the large range, sometimes locally common or abundant at favoured sites, and this has not known to have been greatly altered since the later 20th century.[1]

The habitat occupied by O. unguifera is most often areas dominated by tussocks of tough grasses or low shrubby plant species, vegetation interspersed with occasional trees over arid landscapes, and especially associated with the meeting of clay soils at sandy loams. The marsupial is also recorded at dense stands of Melaleuca species. The conservation status of the species was assessed for the IUCN Red List in 2015 as least concern. The population size is presumed to be large, occurs in a wide range that include conservation reserves, and is not known to be declining at a rate that threatens the species with extinction. The favoured habitat is not commonly found in the protected areas of the Northern Territory or Queensland, and the species is almost unknown in conservation zones in Western Australia; this may make O. unguifera vulnerable to threatening factors resulting from alterations to land use and fire regimes.[1]

The red fox (Vulpes vulpes), deliberately introduced during colonisation and a predator of O. unguifera, is thought to have extirpated their southerly distribution range. As the fox extended its own range to the central regions of Australia, the mammal has had a major impact on the endemic population of small to medium-sized mammals, and this is recognised as a potential threatening factor if the red fox advances to the north of Australia.[1] Research conducted by consultation with Aboriginal people of northern Australia, who are well acquainted and with the animal and capture it for food, indicated a stable population with only a slight decline in Arnhem Land.[16]

Native predators might include Crocodylus johnstoni, a smaller crocodile that occurs in fresh water, which is known to be able to consume this larger species when dead and perhaps able to capture it when alive.[17]

The remains of O. unguifera, preserved as subfossils, have been found in the Grampians region of western Victoria.[18] Fossilised material located at a coastal site of the Montebello area, a sandplain now submerged by the sea, reveals the species once occupied areas south of the Kimberley.[19]

The northern nail-tail wallaby is reported to have been deliberately released at Wilsons Promontory in Victoria during 1924, in a misguided attempt to introduce the species to the area.[20]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Woinarski, J., Winter, J. & Burbidge, A. 2016. Onychogalea unguifera. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T40568A21958021. Downloaded on 08 July 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Gould, J. (1841). "On five new species of kangaroo". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1840: 92–94. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/30571528.

- ↑ Gould, J. (1841). A monograph of the Macropodidæ, or family of kangaroos.]. The Author. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/42174501.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Gould, John (1863). The mammals of Australia. 2. pp. pl.53 et seq. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/49740853.

- ↑ "Onychogalea unguifera: Northern Nailtail Wallaby" (in en-AU). https://bie.ala.org.au/species/urn:lsid:biodiversity.org.au:afd.taxon:eafc5ab3-3505-44f5-94ef-fb27f5446864#.

- ↑ Cutfield, S. (2016). "Common lexical semantics in Dalabon ethnobiological classification". in Austin, P.K.; Koch, H.; Simpson, J.. Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus. London: EL Publishing. pp. 209–227. http://www.elpublishing.org/docs/6/01/LLS-Chapter-15-Cutfield.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Dahl, K. (1897). "Biological notes on north-Australian Mammalia". The Zoologist. 4 1: 189–216 [209–210]. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/39826121.

- ↑ Jackson, S.; Groves, C. (2015) (in en). Taxonomy of Australian Mammals. CSIRO Publishing. p. 361. ISBN 9781486300143. https://books.google.com/books?id=jvznCQAAQBAJ&pg=PT361.

- ↑ Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Diprotodontia". in Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 43–70. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494. http://www.departments.bucknell.edu/biology/resources/msw3/browse.asp?id=11000276.

- ↑ De Vis, C.W. (1884). "Notes on the fauna of the Gulf of Carpentaria". Proceedings of the Royal Society of Queensland. 1: 154–160. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/244203.

- ↑ Gordon, G. (1981). "Northern Nailtail Wallaby". in Ronald Strahan. The Complete Book of Australian Mammals. Angus & Robertson. p. 204.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Thomas, O. (1888). Catalogue of the Marsupialia and Monotremata in the collection of the British Museum (Natural History).. London. pp. 73, 74–75. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/37986510#page/91/mode/1up.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Menkhorst, P. W.; Knight, F. (2011). A field guide to the mammals of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 128. ISBN 9780195573954.

- ↑ Dawson, R.S.; Warburton, N.M.; Richards, H.L.; Milne, N. (2015). "Walking on five legs: investigating tail use during slow gait in kangaroos and wallabies". Australian Journal of Zoology 63 (3): 192–200. doi:10.1071/ZO15007.

- ↑ Ward, Thomas; Fountain, Paul (1907). Rambles of an Australian naturalist. J. Murray. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/22197967.

- ↑ Ziembicki, M.R.; Woinarski, J.C.Z.; Mackey, B. (1 January 2013). "Evaluating the status of species using Indigenous knowledge: Novel evidence for major native mammal declines in northern Australia". Biological Conservation 157: 78–92. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2012.07.004. ISSN 0006-3207.

- ↑ Somaweera, R.; Rhind, D.; Reynolds, S.; Eisemberg, C.; Sonneman, T.; Woods, D. (2018). "Observations of mammalian feeding by Australian freshwater crocodiles (Crocodylus johnstoni) in the Kimberley region of Western Australia". Records of the Western Australian Museum 33 (1): 103–107. doi:10.18195/issn.0312-3162.33(1).2018.103-107.

- ↑ Bird, P.R. (1981). "A New Macropod Species of the Grampians". The Victorian Naturalist (Field Naturalists Club of Victoria.) 98: 67. https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/39906180.

- ↑ Veth, P.; Ditchfield, K.; Hook, F. (17 March 2016). "Maritime deserts of the Australian northwest". Australian Archaeology 79 (1): 156–166. doi:10.1080/03122417.2014.11682032. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/312686750.

- ↑ Seebeck, J.; Mansergh, I. (1998). "Mammals Introduced to Wilsons Promontory". The Victorian Naturalist (Field Naturalists Club of Victoria.) 115 (5). https://biodiversitylibrary.org/page/43405892.

Wikidata ☰ Q112941 entry

|