Place:Salé

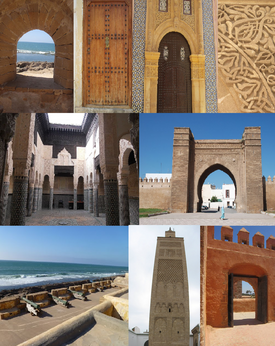

Salé

| |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

| Coordinates: [ ⚑ ] 34°02′N 6°48′W / 34.033°N 6.8°W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Rabat-Salé-Kénitra |

| Established | c. 1030 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jamae Mouatassime[1] |

| Elevation | 0 to 115 m (0 to 377 ft) |

| Population (2014)[2] | |

| • Total | 890,403 |

| • Rank | 5th in Morocco[2] |

| [lower-alpha 1] | |

| Demonym(s) | Slawi |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

Salé (Arabic: سلا, [salaː]; Template:Lang-zgh) is a city in northwestern Morocco, on the right bank of the Bou Regreg river, opposite the national capital Rabat, for which it serves as a commuter town. Founded in about 1030 by the Banu Ifran,[3] it later became a haven for pirates in the 17th century as an independent republic before being incorporated into Alaouite Morocco.

The city's name is sometimes transliterated as Salli or Sallee. The National Route 6 connects it to the cities of Fez and Meknes in the east and the N1 to Kénitra in the north-east. It recorded a population of 890,403 in the 2014 Moroccan census.[2]

History

The Phoenicians established a settlement called Sala,[4][5] later the site of a Roman colony, Sala Colonia, on the south side of the Bou Regreg estuary.[6]

It is sometimes confused with Salé, on the opposite north bank. Salé was founded in about 1030 by Arabic-speaking Berbers[7] who apparently cultivated the legend that the name was derived from that of Salah, son of Ham, son of Noah.[8]

The Banu Ifran Berber dynasty began construction of a mosque about the time the city was founded.[9] The present-day Great Mosque of Salé was built during the 12th-century reign of the Almohad sultan Abu Yaqub Yusuf,[10] although not completed until 1196.[11]

In September 1260, Salé was raided and occupied by warriors sent in a fleet of ships by King Alfonso X of Castile.[12][13] After the victory of the Marinid dynasty, the historic Bab el-Mrissa was constructed by the Sultan Abu Yusuf Yaqub ibn Abd Al-Haqq which remains as a landmark of the city.[14]

Republic of Salé

In the 17th century, Salé became a haven for Barbary pirates, among them the Moriscos expelled from Spain turned corsairs, who formed an independent Republic of Salé.[15] Salé pirates (the well-known "Salé Rovers")[16] enslaved civilians from European coasts; capturing, for, example, 1,000 English villagers in 1625, selling them later in Africa.[17] They sold their crews and sometimes passengers into slavery in the Arabic world.[18] Despite the legendary reputation of the Salé corsairs, their ships were based across the river in Rabat, called "New Salé" by the English.[19][20]

European powers took action to try to eliminate the threat from the Barbary Coast. On 20 July 1629, the city of Salé was bombarded by French Admiral Isaac de Razilly with a fleet composed of the ships Licorne, Saint-Louis, Griffon, Catherine, Hambourg, Sainte-Anne, Saint-Jean; his forces destroyed three corsair ships.[21][22]

20th century

This section does not cite any external source. HandWiki requires at least one external source. See citing external sources. (September 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

During the decades preceding the independence of Morocco, Salé was the stronghold of some "national movement" activists. The reading of the "Latif" (a politically charged prayer to God, read in mosques in loud unison) was launched in Salé and became popular in some cities of Morocco.

A petition against the so-called "Berber Dahir" (a decree that allowed some Berber-speaking areas of Morocco to continue using Berber Law, as opposed to Sharia Law) was given to Sultan Mohamed V and the Resident General of France. The petition and the "Latif" prayer led to the withdrawal and adjustment of the so-called "Berber Decree" of May 1930. The activists who opposed the "Berber Decree" apparently feared that the explicit recognition of the Berber Customary Law (a very secular-minded Berber tradition) would threaten the position of Islam and its Sharia law system. Others believed that opposing the French-engineered "Berber Decree" was a means to turn the table against the French occupation of Morocco.

The widespread storm that was created by the "Berber Dahir" controversy created a somewhat popular Moroccan nationalist elite based in Salé and Fez; it had strong anti-Berber, anti-West, anti-secular, and pro Arab-Islamic inclinations. This period helped develop the political awareness and activism that would lead fourteen years later to the signing of the Manifest of Independence of Morocco on 11 January 1944 by many "Slawi" activists and leaders. Salé has been deemed to have been the stronghold of the Moroccan left for many decades, where many leaders have resided.

Culture

Salé has played a rich and important part in Moroccan history. The first demonstrations for independence against the France , for example, began in Salé. Numerous government officials, decision makers, and royal advisers of Morocco have been from Salé. Salé people, the Slawis, have always had a "tribal" sense of belonging, a sense of pride that developed into a feeling of superiority towards the "berranis", i.e. Outsiders.[citation needed]

Subdivisions

The prefecture is divided administratively into the following:[23]

| Name | Geographic code | Type | Households | Population (2014) | Foreign population | Moroccan population | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bab Lamrissa | 441.01.03. | Arrondissement | 44636 | 174936 | 668 | 174266 | |

| Bettana | 441.01.05. | Arrondissement | 22360 | 95291 | 386 | 94905 | |

| Hssaine | 441.01.06. | Arrondissement | 51858 | 214540 | 470 | 214070 | |

| Layayda | 441.01.07. | Arrondissement | 33522 | 153361 | 163 | 153198 | |

| Sidi Bouknadel | 441.01.08. | Municipality | 4955 | 25255 | 9 | 25246 | |

| Tabriquet | 441.01.09. | Arrondissement | 61101 | 252277 | 629 | 251648 | |

| Shoul | 441.03.01. | Rural commune | 3925 | 19915 | 6 | 19909 | in the Salé Suburbs Circle |

| Ameur | 441.03.05. | Rural commune | 8983 | 46590 | 16 | 46574 | in the Salé Suburbs Circle |

Climate

Salé has a Mediterranean climate (Csa) with warm to hot dry summers and mild damp winters. Located along the Atlantic Ocean, Salé has a mild, temperate climate, shifting from cool in winter to warm days in the summer months. The nights are always cool (or cold in winter, it can reach Sub 0 °C (32 °F) sometimes), with daytime temperatures generally rising about 7 to 8 °C (45 to 46 °F). The winter highs typically reach only 17.2 °C (63.0 °F) in December–February. Summer daytime highs usually hover around 25 °C (77.0 °F), but may occasionally exceed 30 °C (86.0 °F), especially during heat waves. Summer nights are usually pleasant and cool, ranging between 11 °C (51.8 °F) and 19 °C (66.2 °F) and rarely exceeding 20 °C (68.0 °F). Rabat belongs to the sub-humid bioclimatic zone with an average annual precipitation of 560 mm.

Salé's climate resembles that of the southwest coast of the Iberian Peninsula and the coast of Southern California.

Script error: No such module "weather box".

Sports

In December 2017, AS Salé became Africa's basketball club Champion. It was the first continental crown in the club's history.[27]

The A.S.S. is the football club of the city, and the president is Abderrahmane Chokri.[citation needed]

Infrastructure

Transport

Air

Salé's main airport is Rabat–Salé Airport, which is located in Salé but also serves Rabat, the capital city of Morocco.

Trains

Salé is served by two principal railway stations run by the national rail service, the ONCF. These stations are Salé-Tabriquet and Salé-Ville.

Salé-Ville is the main inter-city station, from which trains run south to Rabat, Casablanca, Marrakech and El Jadida, north to Tanger, or east to Meknes, Fes, Taza and Oujda.

Tram

The Rabat–Salé tramway was the first tramway network in Morocco and it connects Salé with Rabat across the river. It was opened on 11 May 2011 after a construction cost of 3.6 billion MAD.[28][29] The network was constructed by Alstom Citadis and is operated by Transdev.[30][31] As of February 2022, the network had two lines with a total length of 26.9 km (17 miles) and 43 stations.[29][32] In 2023, an extension of the network was being planned and is due to be completed by 2028.[28]

Water

Water supply and wastewater collection in Salé was [when?] irregular, with poorer and illegal housing units suffering the highest costs and most acute scarcities.[33] Much of the city used to rely upon communal standpipes, which were often shut down, depriving some neighbourhoods of safe drinking water[33] for indefinite periods of time. Nevertheless, Salé fared better than inland Moroccan locations, where water scarcity was even more acute.[33] Improvements from the government, local businesses and the water distribution companies of Régie de distribution d'Eau & d'Électricité de Rabat-Salé (REDAL) (As of 2010) have meant that this situation has improved drastically.[34]

In popular culture

This section does not cite any external source. HandWiki requires at least one external source. See citing external sources. (September 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

The film Black Hawk Down was partially filmed in Salé, in particular the wide angle aerial shots with helicopters flying down the coastline.

The character Robinson Crusoe, in the early part of Daniel Defoe's novel by the same name, spends time in captivity of the local pirates, the Salé Rovers, and at last sails off to liberty from the mouth of the Salé river - an adventure less well remembered than the protagonist's later sojourn on the desert island.

Notable residents

- Abdellah Taïa, writer

- Abdelwahed Radi, politician

- Abu Zakariya Yahya al-Wattasi, governor of Salé for the Marinids

- Ahmad ibn Khalid al-Nasiri, historian

- Ahmed al-Salawi, writer

- Amina Benkhadra, politician

- Amine Laâlou, athlete

- Chaim ibn Attar, world renowned biblical commentator, talmudist, and posek known for his work "Or HaChayim" on the Pentateuch

- Gnawi, rapper

- Hajj Ali Zniber, writer

- Hayat Lambarki, athlete

- Houcine Slaoui, musician

- Larbi Naji, footballer

- El Mehdi Malki, judoka

- Merouane Zemmama, footballer

- Mohamed Amine Sbihi, politician

- Mohammed Zniber, writer and historian

- Nores (musician), Rapper

- Raphael Ankawa, Chief Rabbi of Morocco and a noted commentator, talmudist, posek, and author

- Reda Rhalimi, basketball player

- Saad Hassar, politician

- Tarik Khbabez, kickboxer

Twin towns – sister cities

Salé is twinned with:[35]

Aryanah, Tunisia

Aryanah, Tunisia Beitunia, Palestine

Beitunia, Palestine Gandiaye, Senegal

Gandiaye, Senegal Grand Yoff, Senegal

Grand Yoff, Senegal Maroua, Cameroon

Maroua, Cameroon Portalegre, Portugal

Portalegre, Portugal

Partner cities

Salé also cooperates with:[35]

See also

- Bouknadel

- Le Bouregreg

References

- ↑ Le Président de la commune urbaine de Salé (in French)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Note de présentation des premiers résultats du Recensement Général de la Population et de l'Habitat 2014" (in fr). High Commission for Planning. 20 March 2015. p. 8. http://rgph2014.hcp.ma/file/165548/.

- ↑ J. D. Fage (1 February 1979). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 663. ISBN 978-0-521-21592-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=ZTNTz3POoZUC&pg=PA663.

- ↑ Glenn Markoe (2000). Phoenicians. University of California Press. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-520-22614-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=smPZ-ou74EwC&pg=PA188.

- ↑ Anna Gallina Zevi; Rita Turchetti (2004). Méditerranée occidentale antique: les échanges. Atti del seminario (Marsiglia, 14-15 maggio 2004). Ediz. francese, italiana e spagnola. Rubbettino Editore. p. 224. ISBN 978-88-498-1116-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=hMV2s_sAICMC&pg=PA224.

- ↑ Kenneth L. Brown (1 January 1976). People of Salé: Tradition and Change in a Moroccan City, 1830-1930. Manchester University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-7190-0623-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=QGK7AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA1.

- ↑ M. Elfasi; Ivan Hrbek; Unesco. International Scientific Committee for the Drafting of a General History of Africa (1988). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century. UNESCO. p. 339. ISBN 978-92-3-101709-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=tw0Q0tg0QLoC&pg=PA339.

- ↑ Jāmiʻat Muḥammad al-Khāmis. Kullīyat al-Ādāb wa-al-ʻUlūm al-Insānīyah; Kullīyat al-Ādāb wa-al-ʻUlūm al-Insānīyah (1969). Hespéris tamuda. 10–13. Editions techniques nord-africaines. p. 92. https://books.google.com/books?id=Mu0PAQAAMAAJ&q=%22Sal%C3%A9%22%20%22Ham%22%20%22Noah%22.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ar). http://www.habous.gov.ma/ar/detail.aspx?ID=1312&z=359&s=99. - ↑ Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (5 March 2014). Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Routledge. p. 617. ISBN 978-1-134-25986-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=6XMBAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA617.

- ↑ Janet L. Abu-Lughod (14 July 2014). Rabat: Urban Apartheid in Morocco. Princeton University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-4008-5303-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=NKP_AwAAQBAJ&pg=PA57.

- ↑ Dufourcq, Charles-Emmanuel (1966) (in fr). Un projet castillan du XIIIe siècle : la croisade d'Afrique. Faculty of Arts. p. 28.

- ↑ Joseph F. O'Callaghan (31 August 1983). A History of Medieval Spain. Cornell University Press. p. 364. ISBN 0-8014-9264-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=yA3p6v3UxyIC&pg=PA364.

- ↑ أنا باب المريسة وهذه حكايتي. El Mghriby. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ↑ Alan G. Jamieson (15 February 2013). Lords of the Sea: A History of the Barbary Corsairs. Reaktion Books. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-86189-946-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=7DlMqY9OQXAC&pg=PA106.

- ↑ Adrian Tinniswood (11 November 2010). Pirates of Barbary: Corsairs, Conquests and Captivity in the Seventeenth-Century Mediterranean. Penguin Publishing Group. p. 133. ISBN 978-1-101-44531-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=IBSVMivndEQC&pg=PT133.

- ↑ Giles Milton (2005). "A New and Deadly Foe" (in en). White Gold • The Extraordinary Story of Thomas Pellow and North Africa's One Million European Slaves (Large Print ed.). Oxford: Isis Publishing Ltd. p. 14. ISBN 0-7531-5647-4. "summer of 1625, the mayor of Plymouth reckoned that 1,000 skiffs had been destroyed, and a similar number of villagers carried off into slavery. These miserable captives were taken to Salé"

- ↑ D'Maris Coffman; Adrian Leonard; William O'Reilly (5 December 2014). The Atlantic World. Routledge. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-317-57605-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=80y2BQAAQBAJ&pg=PA178.

- ↑ Roger Coindreau (2006). Les corsaires de Salé. Eddif. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-9981-896-76-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=TaaSQECw4IcC&pg=PA45.

- ↑ Alan G. Jamieson (15 February 2013). Lords of the Sea: A History of the Barbary Corsairs. Reaktion Books. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-86189-946-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=7DlMqY9OQXAC&pg=PA104.

- ↑ Coindreau 2006. p. 192

- ↑ Jamieson 2013, p. 109

- ↑ 2014 Morocco Population Census(in Arabic)

- ↑ "Rabat Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. ftp://ftp.atdd.noaa.gov/pub/GCOS/WMO-Normals/TABLES/REG__I/FM/60135.TXT.

- ↑ "Klimatafel von Rabat-Salé (Int. Flugh.) / Marokko" (in de). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world. Deutscher Wetterdienst. http://www.dwd.de/DWD/klima/beratung/ak/ak_601350_kt.pdf.

- ↑ "Station Rabat" (in fr). Météo Climat. http://www.dwd.de/DWD/klima/beratung/ak/ak_601350_kt.pdf.

- ↑ Basketball : L’AS Salé champion d’Afrique, La Vie éco, 21 December 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2017 (in French)

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 El Masaiti, Amira (2023-07-20). "Rabat Tramway network extends in the directions of Temara and Sale" (in en-US). https://en.hespress.com/67795-rabat-tramway-network-extends-for-kilometers-in-the-directions-of-temara-and-sale.html.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 L'Opinion. "Tramway / Rabat-Salé : 7,8 MDH pour la 3ème phase de développement" (in fr). https://www.lopinion.ma/Tramway-Rabat-Sale-78-MDH-pour-la-3eme-phase-de-developpement_a29624.html.

- ↑ "Morocco: Inauguration of tramway line between Rabat and Salé" (in en). https://www.icafrica.org/en/news-events/infrastructure-news/article/morocco-inauguration-of-tramway-line-between-rabat-and-sale-1965/.

- ↑ "Qui sommes-nous ?" (in fr-FR). https://www.tram-way.ma/fr/qui-sommes-nous/.

- ↑ "MISE EN SERVICE COMMERCIALE DE L’EXTENSION DE LA LIGNE 2 DU RESEAU DU TRAMWAY DE RABAT SALE LE MERCREDI 16 FERVIER 2022" (in fr-FR). https://www.tram-way.ma/fr/mise-en-service-commerciale-de-lextension-de-la-ligne-2-du-reseau-du-tramway-de-rabat-sale-le-mercredi-16-fervier-2022/.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Guillaume Benoit and Aline Comeau, A Sustainable Future for the Mediterranean (2005) 640 pages

- ↑ Richard N. Palmer (2010). World Environmental and Water Resources Congress 2010: Challenges of Change. ASCE Publications. p. 826. ISBN 978-0-7844-7352-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=hPskluvG7OQC&pg=PA826.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "Partenariats" (in fr). Salé. https://fr.villedesale.ma/commune-de-sale/travaux-du-conseil/partenariats-et-accrods/.

External links

- Salé entry in LexicOrient

- Le portail de la ville de Salé

"Sallee". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

"Sallee". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

Template:RabatTemplate:Rabat-Salé-Kénitra [ ⚑ ] 34°02′N 6°48′W / 34.033°N 6.8°W

|