Engineering:Women in aviation

Women have been involved in aviation from the beginnings of both lighter-than air travel and as airplanes, helicopters and space travel were developed. Women pilots were also formerly called "aviatrices" (singular "aviatrix"). Women have been flying powered aircraft since 1908; prior to 1970, however, most were restricted to working privately or in support roles in the aviation industry.[1] Aviation also allowed women to "travel alone on unprecedented journeys".[2] Women who have been successful in various aviation fields have served as mentors to younger women, helping them along in their careers.[3]

Within the first two decades of powered flight, female pilots were breaking speed, endurance and altitude records. They were competing and winning against the men in air races, and women on every continent except Antarctica had begun to fly, perform in aerial shows, parachute, and even transport passengers. During World War II, women from every continent helped with war efforts and though mostly restricted from military flight many of the female pilots flew in auxiliary services. In the 1950s and 1960s, women were primarily restricted to serving in support fields such as flight simulation training, air traffic control, and as flight attendants. Since the 1970s, women have been allowed to participate in military service in most countries.

Women's participation in the field of aviation has increased over the years. In 1909, Marie Surcout founded the world's first female pilot organization, the Aéroclub féminin la Stella. After the 1929 women-only air race in the United States during the National Air Races, 99 women out of the 117 holding U.S. pilot licenses at the time founded the first American female pilot organization named the Ninety-Nines after the number of members. Within the United States, during 1930, there were around 200 women pilots but in five years there were more than 700.[4] Women of Aviation Worldwide Week has reported that after 1980, the increase in gender parity for women pilots in the United States has been stagnant.[5] The global percentage of women airline pilots is 3%. While the overall number of female pilots in aviation has increased the percentage remains the same.

History

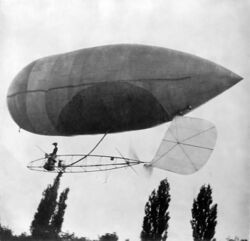

The first woman known to fly was Élisabeth Thible, who was a passenger in an untethered hot air balloon, which flew above Lyon, France in 1784.[6] Four years later, Jeanne Labrosse became the first woman to fly solo in a balloon and would become the first woman to parachute, as well.[7][8] Sophie Blanchard took her first balloon flight in 1804, was performing as a professional aeronaut by 1810 and was made Napoleon's chief of air service in 1811.[9] Blanchard, died in a spectacular crash in 1819.[10] In June 1903, Aida de Acosta, an American woman vacationing in Paris, convinced Alberto Santos-Dumont, pioneer of dirigibles, to allow her to pilot his airship, becoming probably the first woman to pilot a motorized aircraft.[11]

Starting 1906, another inventor of aircraft, Emma Lilian Todd began designing her own airplanes.[12] Todd first started studying dirigibles before she moved onto designing airplanes.[13] Todd's first plane flew in 1910 and was piloted by Didier Masson.[12] A woman who was an early parachutist, Georgia "Tiny" Broadwick started working with barnstormer, Charles Broadwick at age 15 in 1908.[14][15] She made her first jump in 1908, and in 1913, became the first woman to jump from an aircraft.[15][14] Broadwick, in 1914, was also the person who gave the first demonstrations of parachute jumping to the United States government.[15] When she retired in 1922, she had completed 1,100 jumps.[14]

The first woman passenger in an airplane was Mlle P. Van Pottelsberghe de la Poterie who flew with Henri Farman on several short flights at an airshow in Ghent, Belgium between May and June 1908. Soon after, in July, 1908, sculptor Thérèse Peltier was taken up as a passenger by Léon Delagrange[16] and within a few months had been reported as making a solo flight in Turin, Italy, flying around 200 meters in a straight line about two and a half meters off the ground. Edith Berg, an American, who flew as a passenger with Wilbur Wright in Paris in October 1908, was the inspiration of the hobble skirt designed by Paul Poiret. [17][18]

The first machine-powered flight was accomplished by the Wright Brothers on December 17, 1903. Both brothers felt that it was important to recognize the contributions of Katherine Wright to their work.[19] She found teachers who could help with the Wright's flying experiments.[20] Katherine, although not flying with her brothers until later, in 1909,[19] knew "everything about the working of their machines".[21] Katherine supported them financially, giving them her savings and also supported them emotionally.[22] When Orville Wright was injured in 1908, Katherine moved close to the hospital to take care of him.[23] Later, after the Wright brothers patented their aircraft in 1906, she worked as their executive secretary.[20] In 1909, she traveled to Europe to become the social manager for her brothers.[20] Her brothers were very introverted and relied on Katherine to help promote their work.[24] Katherine was considered the "silent partner" of the Wright Brothers by The World Magazine.[21] The Saint Louis Post-Dispatch called her the "inspiration of her brothers in their experiments".[25]

1910s

Early pioneers include French Raymonde de Laroche who was the first woman in the world to successfully pass a flight test and earn a pilot licence on March 8, 1910. In 1909, a pilot licence had become required to fly commercially and participate in air shows.[8] Seven other French women followed her, earning pilot's licenses within the next year.[26] One of these, Marie Marvingt, 3rd Frenchwoman licensed for airplanes,[27] but first French woman balloonist licensed in 1901,[28] became the first woman to fly in combat completing bombing raids over Germany.[29][30] Marvingt tried to get the government to outfit air ambulances prior to the war and became the world first certified Flight Nurse.[30] Hélène Dutrieu became the first woman pilot in Belgium, obtaining the 27th license issued in her country in 1910 and the second female licensed in Europe.[31][32] Later that same year, she became the first woman to fly with a passenger.[8] In 1910, even before she earned her pilot's license, Lilian Bland a British woman living in Northern Ireland, designed and flew a glider in Belfast.[33]

Blanche Scott always claimed to be the first American woman to fly an airplane, but as she was seated when a gust of wind took her up on her brief flight in September 1910, the "accidental" flight went unrecognized.[34] Within two years, she had established herself as a daredevil pilot and was known as the "Tomboy of the Air",[35] competing in air shows and exhibitions, as well as flying circuses.[36][35] On October 13, 1910, Bessica Raiche received a gold medal from the Aeronautical Society of New York, recognizing her as the first American woman to make a solo flight.[37] Harriet Quimby became the USA's first licensed female pilot on August 1, 1911, and the first woman to cross the English Channel by airplane the following year.[38] Thirteen days after Quimby,[39] her friend Matilde E. Moisant an American of French Canadian descent[40] was licensed and began flying in air shows.[41]

Within a fortnight, Lydia Zvereva had obtained the first female Russian license[42] and by 1914 she performed the first aerobatic loop made by a woman.[43] Hilda Hewlett became the first British woman to earn a pilot's license on August 29, 1911, and taught her son to fly that same year.[8] Cheridah de Beauvoir Stocks became the second United Kingdom woman to gain a Royal Aero Club aviator's licence, on 7 November 1911.[44] In September 1910, Melli Beese became Germany's first woman pilot and[45] the following year began designing her first airplane which was produced in 1913.[46] On October 10, 1911, Božena Laglerová a Czech native of Prague, obtained the first Austrian license for a woman and nine days later secured the second German license for a woman.[47] On 7 December 1910, Jane Herveu, who had previously been involved in automobile racing was licensed in France and began participating in the Femina Cup.[48] Lilly Steinschneider became the first female pilot in the Austro-Hungarian Empire on August 15, 1912.

Rosina Ferrario, first female pilot of Italy, earned her license on January 3, 1913, and was as unsuccessful as Marvingt had been to get her government or the Red Cross to allow women to transport wounded soldiers during World War I.[49] Elena Caragiani-Stoenescu, Romania's first woman pilot got the same response from her government about flying for the war effort and turned to journalism.[50] On December 1, 1913, Lyubov Golanchikova signed a contract to become the first female test pilot. She agreed to test "Farman-22" aircraft manufactured in the Chervonskaya airplane workshop of Fedor Fedorovich Tereshchenko (ru)[51] The first woman on the African Continent to earn a pilot's license was Ann Maria Bocciarelli of Kimberley, South Africa.[52]

In 1916, Zhang Xiahun (Chinese: 張俠魂) became China's first female pilot when she attended an airshow of the Nanyuan Aviation School and insisted that she be allowed to fly. After circling the field, tossing flowers, she crashed, becoming a national heroine when she survived.[53][54] Katherine Stinson became the first woman air mail pilot, when the United States Postal Service contracted her to fly mail from Chicago to New York City in 1918.[55] The following year, Ruth Law flew the first official U.S. air mail to the Philippines .[56]

Women were also involved in teaching others how to fly. Hilda Hewlett and Gustave Blondeau teamed up in 1910 to start the first flying school in England, the Hewlett-Blondeau School.[57] The school had only one plane with which to instruct students and was open for two years.[58] Charlotte Möhring, the second German woman to earn a pilot's license, worked as a manager of a flying school in 1913.[59]

1920s

Men and women after World War I were able to purchase "surplus and decommissioned planes".[60] Wanting to fly, but with little demand after the war, pilots purchased the planes and went from town to town offering rides. Creating attractions to bring in crowds, these daredevils performed stunts, loops and began wing walking to attract more customers. The aerialists and pilots formed flying circuses sending promoters ahead of them to hang posters promoting their barnstorming feats.[61]

In 1920, Phoebe Fairgrave, later Omlie, at the age of eighteen determined to make her aviation career as a stuntwoman.[62][63] By 1921, she had set a world women's parachute drop record of 15,200 feet[62][64] and worked as a wing walker for the Fox Moving Picture Company's The Perils of Pauline series. By 1927, Omlie earned the first transport pilots license and airplane mechanics license issued to a woman.[65] Another stuntwoman, Ethel Dare had perfected walking from one plane to another by 1920,[66] the first woman to perform the feat.[61]

Bessie Coleman was the first African American woman to become a licensed airplane pilot in 1921.[67] That same year,[68] Annie Langstaff, first law graduate of McGill University[69] began taking flying lessons and in 1922 was proclaimed in an article in Maclean's Magazine, as Canada's first woman to fly.[70] It was Eileen Vollick who was the first women in Canada to obtain a Pilots License in 1928. That year, Japan's first woman pilot Tadashi Hyōdō earned her license.[71] Kwon Ki-ok of Korea became the first female licensee of that country in 1925 and after World War II, became instrumental in helping establish the Republic of Korea Air Force .[72][73] German Marga von Etzdorf was the first woman to fly for an airline when she began co-piloting for Lufthansa in 1927[74] and piloting solo on commercial Junkers F13 on 1 February 1928.[75]

In the late 1920s, women continued to compete in air races and contests related to flying.[76] In 1929, Pancho Barnes moved to Hollywood to work as the first woman stunt pilot. Besides working on such films as Howard Hughes' Hell's Angels (1930),[77] she also founded the Associated Motion Pictures Pilots Union in 1931.[78] The first Women's Air Derby or Powder Puff Derby, an official women-only race from Santa Monica, California to Cleveland, Ohio, was held as part of the 1929 National Air Races and was won by Louise Thaden.[79]

Marie Marvingt of France, who had first proposed the idea of using airplanes as ambulances in 1912 continued to promote her idea successfully in the 1920s.[80] During the French colonial wars, Marvingt evacuated injured military personnel with Aviation Sanitaire, a flying ambulance service.[81] Canadian Eileen Vollick became the first licensed female pilot in 1928 at age 19, and Elsie MacGill became the first woman to earn a master's degree in aeronautical engineering in 1929.[82] Janet Hendry became the first woman pilot in Scotland, earning her "A" licence on 3 December 1928.[83] On November 2, 1929, at Curtiss Field in Valley Stream, New York, 26 women pilots gathered and formed an international organization to provide mutual support for advancing women pilots and named themselves the Ninety-Nines, after the number or charter members.[84]

1930s

The 1929 stock market crash and ensuing depression, coupled with more stringent safety regulations, caused many of the flying circuses and barnstorming circuits to fold.[61] During the decade, options for women pilots in the United States were limited mainly to sales, marketing, racing and barnstorming and being an instructor pilot.[85] In 1930, Ellen Church, a pilot who was unable to secure work flying, proposed to airline executives that women be allowed to act as hostesses on planes. She was hired on a three-month trial basis by Boeing Air Transport and selected as one of the first seven flight attendants for airlines. These first flight attendants were required to be under 115 pounds, nurses and unmarried.[86][87]

Various "firsts" were achieved by women in the 1930s. In 1930, English aviator Amy Johnson, made the first England to Australia flight by a woman.[88] The same year, inspired to learn to fly by Johnson's flight, Mrs Victor Bruce became the first person to fly from England to Japan, the first to fly across the Yellow Sea, and the first woman to fly around the world alone (crossing the oceans by ship) in her Bluebird plane[89]

Antonie Strassmann, a German emigre to the US, became the first woman to successfully cross the Atlantic aboard an aircraft, traveling in May 1932 with a team on a Dornier Do X flying boat.[90] In the fall of the same year, Strassmann piloted a Zeppelin from Germany to Pernambuco in Brazil.

On 19 September 1931, the first all women's flying meeting in the UK was organised by Molly Olney and Mrs Harold Brown through the Northamptonshire Aero Club, at Sywell.[91][92][93]

In May 1932, American Amelia Earhart became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic.[19][94][95] She urged the public to encourage and enable young women to become airplane pilots and in 1936 and 1937, she taught students at Purdue University, which was "one of the few U.S. colleges to offer aviation classes to women".[96][97]

In 1933, Lotfia ElNadi became the first Egyptian woman and first Arab woman to earn a pilot's license.[98] That same year, Marina Raskova became the first Russian woman navigator for the Soviet Air Forces .[99] The following year she began teaching as the first female instructor at the Zhukovsky Air Force Academy[100] and then in 1935 received her certification as a flight instruments trainer.[101]

Hazel Ying Lee, a dual American-Chinese citizen, earned her pilot's license in 1932 in the United States. She went to China to volunteer to serve in the Chinese Army after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, but was rejected due to her sex.[102] In 1934, Chinese actress Lee Ya-Ching obtained a pilot's license in Switzerland; the following year, she obtained the first license for a woman from the American Boeing School of Aeronautics; and, in 1936, she became the first woman licensed by China as a pilot. She went on to found a civilian flying school in Shanghai that same year.[103][104]

In 1935, Nancy Bird Walton obtained the first Australian license allowing a woman to carry passengers so that she could fly an ambulance service for the Royal Far West Children's Health Scheme. She later founded the Australian Women Pilots' Association.[105]

That same year, Phyllis Doreen Hooper earned the first women pilot's license in South Africa . The following year, she became the first female licensed as a commercial pilot and within 2 years had become the first South African woman flight instructor.[106]

In France, Suzanne Melk, was the first known women in her country to fly and the first women in Europe to receive a pilot's license in 1935.[107]

Sarla Thakral was first Indian woman to fly, earning her aviation pilot license in 1936 in a Gypsy Moth solo. She later completed over 1000 hours of flight time.[108][109]

In 1936, Hanna Reitsch of Germany became one of the first persons to fly a fully controllable helicopter[110][111] and within two years, she earned the first woman helicopter pilot's license.[112][113]

Women had been barred from prestigious Bendix Race following the death of Florence Klingensmith, but were allowed to compete from 1935.[114] In 1936, women not only took first place, but also second and fifth.[115] The winners were Louise Thaden and Blanche Noyes.[116] Laura Ingalls came second and Earhart was fifth. In 1938, the race was won by Jacqueline Cochran.[114]

In 1937, Sabiha Gökçen of Turkey became the first trained woman combat pilot, participating in search operations and bombing flights during the Dersim Rebellion. While Gökçen was not the first to have participated in military operations, she was the first woman to have been trained as a military pilot, graduating from the Aircraft School (Tayyare Mektebi) in Eskişehir.[117]

In 1939, the South African Women's Aviation Association (SAWAA) was formed with 110 women members. Colloquially known as the Women's Civil Air Guard, within the year, membership had swelled to between 3000 and 4000 members. With the outbreak of war, the organization changed focus to become the Women's Auxiliary of the South African Air Force .[118]

1940s

As World War II began, women became involved in combat. In the United States, prior to the war, pilots typically flew only in good weather, so that they could judge ground position. Flying in combat required pilots to fly in varying conditions, and a push for instrument training began. By 1944, around 6,000 women had been trained as Link Trainer operators and were teaching male pilots how to read instruments. WAVES like Patricia W. Malone transitioned after the war to commercial flight simulation instruction, where women dominated the industry of flight training operators.[119]

In 1939, Jacqueline Cochran wrote to the first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, about using women pilots in the military.[120] Later, Nancy Harkness Love also made a similar request to the US Army, however both women's ideas were put on hold until 1942. Love was then put in command of the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron [WAFS], which developed a reputation for quiet efficiency and became a well-respected unit.[120] General Henry Arnold on September 14, 1942, put Cochran in charge of a new program called the Army Air Forces Women's Flying Training Detachment (WFTD).[120] By August 5, 1943, the WFTD was merged with the WAFS to form the Women Airforce Service Pilots (WASP).[120] The WASPs supported the military in various ways, flying new planes from factories to Army Air Force bases, worked as test pilots, worked as flying chauffeurs and helped tow targets for antiaircraft gunnery practice.[121] The WASPs never gained full military benefits, the organization was disbanded in December 1944. WASPs finally earned veteran status retroactively in 1979.[121]

Besides working as women pilots, American women also started working as air traffic controllers during WWII.[122] Commander Frances Biadosz was the only WAVE to wear wings for air-navigation during World War II.[123] Women in the United States were also hired by the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) to work as scientists and engineers, as well as analysts, reviewing data from windtunnels on airplane prototypes.[124]

In 1940, Major Phyllis Dunning (née Phyllis Doreen Hooper) became the first South African woman to enter full-time military service as the Commander of the South African Women's Auxiliary Air Force (SAWAAF).[125] In 1941, the Southern Rhodesia Women's Auxiliary Air Service was commissioned. Within a few months over 100 women recruits were providing clerical services, sewing skills, parachute packing, and serving as drivers, equipment assistants and mechanics.[126]

The Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA), a British civilian operation during World War II, had 166 women pilots, (one in eight of all ATA pilots) under the command of Pauline Gower.[127] The first eight women pilots, Joan Hughes, Margaret Cunnison, Mona Friedlander, Rosemary Rees, Marion Wilberforce, Margaret Fairweather, Gabrielle Patterson, and Winifred Crossley Fair were accepted into service on 1 January 1940. Fifteen of these women pilots lost their lives in the air, including British recordbreaking aviator Amy Johnson and Canadian born Joy Davison.[128] Ida Veldhuyzen van Zanten was the only Dutch woman in the ATA, having escaped the occupied Netherlands as an Engelandvaarder.[129] Margot Duhalde, a Chile an woman, flew transport missions for the ATA during World War II and after the war became the first woman pilot of the French Air Force , flying transports to Morocco. For her services, Duhalde was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour in 1946.[130] Valérie André, a neurosurgeon and member of the French army, became the first woman to fly a helicopter in combat, while serving in Indochina (1945). The Royal Canadian Air Force created a Women's Division in 1942, offering women 2/3 the pay of their male counterparts. Though barred from combat and flying, women performed aircraft maintenance and served in air traffic control, in addition to other duties. By the end of the war, over 17,000 Canadian women had served in the Women's Division either at home or abroad.[131]

Korean Lee Jeong-hee (ko), who had earned her pilot's license in 1927, joined the Republic of Korea Air Force in 1948 and was appointed first lieutenant. She was the founding commander of the Women's Air Force Corps in 1949, but was captured and taken to North Korea when the Korean War broke out.[132][133]

Unlike other countries fighting in WWII, the Soviet Union created an all-woman combat flight unit, the 588th Night-Bomber Air-Regiment or the Night Witches. This group of the Soviet Air Forces , flew harassment bombing and precision bombing missions from 1942 to the end of the World War II.[134] The organization was first formed by Joseph Stalin on October 8, 1941, and all of the women were volunteers.[135] The Night Witches flew 30,000 missions and "dumped 23,000 tons of bombs on the German invaders": the unit was granted both 'Guards' status and a battle-honour: 'Taman-sky' (for their work during the Battle of Taman), and was therefore re-numbered to finish the war as the 46th 'Tamansky' Guards Night-Bomber Air-Regiment. [135] The Soviets also had the only women to be considered flying aces. Lydia Litvyak was credited with different numbers of kills from various sources, but in 1990, the tally was given as 12 solo kills and 3 shared kills.[136][137] Yekaterina Budanova fought combat missions over Saratov and Stalingrad and was credited with 11 kills.[136][138]

In 1948, Ada Rogato, Brazil's first licensed woman pilot, became the first female agricultural pilot when she was hired by the government to crop dust coffee fields and eliminate the borer beetle that was plaguing the crop.[139][140] The following year, Rogato became the first woman to fly solo over the Andes and in 1951, flew from Tierra del Fuego to Alaska, a solo flight which would take her across South America, Central America and North America.[139][141] In 1948, Isabella Ribeiro de Cabral, who became Isabella de Freitas the following year, became the first woman pilot of Trinidad and Tobago.[142] It would be another forty years, in 1988, before the first Trinidadian woman, Wendy Yawching became a captain.[143][144]

1950s

In 1951, the People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) of China enrolled 55 women trainees. When they graduated, the following year, the women represented 6 communication operators, 5 navigators, 30 on-board aircraft mechanics and 14 pilots. A second class of 160 trainees entered PLAAF in 1956, but only 44 of them completed their training.[145]

In late 1952, with the Korean War in full swing, the North Korean Air Force was the only one in the world with female jet fighter pilots. One of them, Tha Sen Hi, flew MiG-15s in combat and eventually rose to squadron leader. She was honoured with the title of Hero of the Korean People's Democratic Republic.[146]

In 1952, Earsley Barnett, American wife of Major Carl Barnett, founder of Wings Jamaica, earned the first pilot license granted to a woman in Jamaica. She later became the first Jamaican flight instructor, as well as a commercial pilot.[147]

Jacqueline Cochran became the first woman to break the sound barrier in 1953. She had to use a Canadian Canadair Sabre 3 as the U.S. military refuse her access to American aircraft. By June 1953, she was the holder of "all but one of the principal world airplane speed records for straightaway and closed-course flight" for women.[148] On June 14, 1963, Jacqueline Auriol became the first woman to fly at twice the speed of sound with a Dassault Mirage IIIR.

During the Korean War, former WASPs were asked to join active duty in the United States Air Force .[149] Thirteen percent of the WAVES recruits by 1952 were air selected for air training, which included positions as air control personnel, aerographer's mates, electronics technicians and as other support personnel. In 1953, the WAVES lifted a ban on women serving as mechanics.[123] Kim Kyung-Oh (ko) was the only South Korean woman to serve as a pilot in the ROK Air Force during the Korean War.[150][151]

Organisations were formed, such as the Australia Women Pilots' Association (AWPA).[152] Another organization was the Whirly-Girls, started by Jean Ross Howard Phelan in 1955 for women helicopter pilots. She started the group as an informal interest group, but formalized it in order to better help the members network and support each other in the male-dominated field.[153]

Pakistan modeled its air force on the Royal Air Force during the late 1950s. This allowed for more women to become involved in the military in Pakistan.[154] In 1958 Dorothy Rungeling of Canada became her country's first woman to solo pilot a helicopter.[155]

In the 1950s and 1960s, air travel was expensive and few people of color could afford to fly. U.S. segregation laws were slowly being overturned to lift barriers for not only travel, but for employment opportunities.[156][157] Coupled with the influx of workers from the Indian subcontinent and the Caribbean, and the independence movements in Africa and the Caribbean, British need for labor in the post-war period made recruiting of 'coloured labour' in the same period a necessity.[158] The following decades would increasingly see more women from former colonies enter aviation.[159][160][161][162][163][164][165]

1960s

In the 1960s, stewardesses, as female flight attendants were known, were considered glamorous and exotic adventurers. Frank Sinatra's song Come Fly with Me gave birth to the jet set.[166] Adding to the allure, Bernard Glemser's novel, Girl on a Wing, and the British movie based on it, Come Fly with Me (1963), depicted stewardesses as stylish seekers of romance.[167] Wearing custom-fitted uniforms, attendants were career women, whose looks, marital status and childlessness were guarded by industry executives, much as Hollywood starlets had been. On the one hand, they were to project an ideal of womanhood, but on the other, they were used to sell airline travel through their sexuality. The double standard that they faced as well as the glamorous lifestyle they lived, shot to the best-seller's list with the publication in 1967 of the book, Coffee, Tea or Me?[166] In 1963, stewardesses who held a press conference on airlines' policy of retiring stewardesses at 32, caught the attention of the country. The press conference focused attention on the airlines narrow standard of "feminine allure".[168]

In 1960, Olga Tarling became the first woman air traffic controller in Australia[169] and Yvonne Pope Sintes and Frankie O'Kane become the first female British air traffic controllers.[170] That same year, Alia Menchari became the first woman Tunisian pilot.[160] In 1961, Lucille Golas attained the first pilot license for a woman in Guyana to assist her husband in his mining business.[171] Asegedech Assefa became the first Ethiopian woman to earn a pilot's license in 1962.[172] That same year, Jacqueline Cochran became the first woman to fly a jet across the Atlantic Ocean.[8] She was also the first woman to break the sound barrier. Throughout the decade, she and Jacqueline Auriol[173] of France traded women's speed and distance records what would be known as the "battle of the Jackies". Jacqueline Auriol was the first woman to fly at twice the speed of sound in 1963.

A privately funded project, of William Lovelace, the Woman in Space Program recruited women pilots in the U.S. to test them for suitability for the space program. Thirteen of the recruits passed NASA's physical requirements. Scheduled for additional testing, the United States Navy canceled use of their facilities as there were no NASA officials involved. Public hearings were held by a special Subcommittee of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics in 1962. Because NASA required all astronauts to attain an engineering degree and be graduates of military jet piloting test programs, none of the women could meet the entry prerequisites. The subcommittee took no action after the hearing. The following year, Valentina Tereshkova,[174] an amateur Russian parachute jumper became the first woman in space.[175]

In 1963, Betty Miller became the first woman to fly solo across the Pacific Ocean[176] and Anne Spoerry, a French doctor living in Kenya became the first female member of the African Medical and Research Foundation's "Flying Doctors", operating her plane through the bush to provide needed medical assistance in remote areas.[177] In 1964, women again made history when Geraldine Mock became the first woman to circumnavigate the globe.[8] In 1966, Soviet pilot Galina Gavrilovna Korchuganova competed at the World Aerobatic Championship in Moscow and won gold in the women's individual competition, becoming the first women's world aerobatics champion.[178]

Because of the unpopularity of the Vietnam War in the United States, men were not volunteering at high enough rates; however, many women were being turned away because of limits on women's work in the military. In 1967, a law was passed allowing more women into the military and to be promoted to high ranks.[179] In 1969, Kucki von Gerlach obtained the first pilot's license issued to a woman in South West Africa, now Namibia.[159] That same year, Turi Widerøe of Norway became the first female pilot for Scandinavian Airlines.[180] Turi Widerøe had for years been a pilot for her father's company Widerøe, which today is the largest regional airline in the Scandinavian countries. Turi Widerøe is still today recognized as the western world's first woman commercial pilot for a major airlines after she joined Scandinavian Airlines in 1967.

1970s

Until the 1970s, aviation had been a traditionally male occupation in the United States. Commerce Department regulations virtually required pilots to have flown in the military to acquire sufficient flight hours, and until the 1970s, the U.S. Air Force and Navy barred women from flying[181] and they were routinely denied work in commercial piloting.[182] The US military did not open fighter jet flights to women until 1993.[183] Women eventually began to enter U.S. major commercial aviation in the 1970s and 1980s, with 1973 seeing the first female pilot at a major U.S. airline, American Airlines. American also promoted the first female captain of a major U.S. airline in 1986 and the following year had the first all-woman flight crew.[184] In other countries, women were starting to fly as pilots, such as Turi Widerøe, who was hired in late 1968, for Scandinavian Airlines System and Aeroflot had already hired women pilots.[185]

In the 1970s, women were again, for the first time since WWII, permitted to fly in the United States Armed Forces, beginning with the Navy and the Army in 1974, and then the Air Force in 1976.[186] By the mid-1970s, women were predicting that there would be a large increase in female pilots because of the women's liberation movement.[187] Louise Sacchi was the first international woman ferry pilot who flew planes across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans over 340 times, more than any other non-airline pilot.[188] In 1971, she set a women's speed record by flying a single-engine land plane from New York to London in 17 hours and 10 minutes, a record that still stands today.[188][189] Sacchi was the first woman to win the Godfrey L. Cabot Award for distinguished service to aviation.[188][190] The first graduating class of ten female Air Force officers earned their Silver Wings on September 2, 1977. These ten women were part of Class 77-08 and graduated at Williams Air Force Base.[191] In 1978, a group of former WASPs formed the Women's Military Pilots Association (WMPA).[192]

In 1975, Yola Cain became the first Jamaican-born commercial pilot and flight instructor.[147] The following year, Cain became the first female pilot with the Jamaica Defence Force and in the 1980s would become the first woman pilot for TransJamaica Ltd. Four years later, in 1979, Jamaican Maria Ziadie-Haddad became one of the first women in the Western Hemisphere to become a commercial jet airline pilot when she was hired as the first woman pilot of Air Jamaica, as a Boeing 727 second officer.[161] Another Jamaican, Michele Yap, became the first female airline captain in the Caribbean flying the Leeward Islands Air Transport's Twin Otter in 1988. The following year, Captain Yap was the first to pilot an all-female crew in the Anglo-Caribbean.[147]

On 9 September 1976, Asli Hassan Abade soloed her first flight as the only female pilot in the Somali Air Force .[162][193] In 1977, Cheryl Pickering-Moore and Beverley Drake of Guyana became the first two women pilots of the Guyana Defence Force.[194] Drake was transferred a few months later as the first female pilot of the Guyana Airways Corporation, she would go on in the 1990s to become the first woman and African-American senior inspection analyst working for the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board.[163] Jill Brown-Hiltz joined Texas International Airlines as a pilot in 1978, becoming the first African American woman to fly for a commercial airline in the United States.[195] That same year, Chinyere Kalu, at the time Chinyere Onyenucheya became, Nigeria's first female pilot.[164] In 1979, Koh Chai Hong became the first woman pilot in the Republic of Singapore Air Force (RSAF). Continuing her military career, Koh became one of the first two female Lieutenant-Colonels in 1999.[165] Bahamian Patrice Clarke, later Washington, entered Embry–Riddle Aeronautical University, Daytona Beach in 1979. Three years later she would become the school's first black woman to graduate with a BS in aeronautical science and her commercial pilot's certification.[196] She would go on to become the first woman pilot hired by Bahamasair[197] and later the first black female to command airplanes in the U.S. for a major carrier service when she was promoted to captain by United Parcel Service (UPS) in 1994.[198][199]

In 1977, Barbara Ann Christie was recorded as the first woman police pilot in the United States by the American Business Reference Inc. while working for Horsham Township Police Department in Pennsylvania. She contributed in excess of 1,000 hours of personal time to the Air Ambulance and Helicopter Unit without remuneration of any kind.[200]

Close of the twentieth century

At the close of the century, legal efforts to eliminate barriers of race and sexism in the aviation sector resulted in industry modifications in hiring practices. In the United States, in the late 1970s the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission found violations of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which the court monitored over the next decades and decreed in 1995 had been sufficiently addressed.[201] In Africa, lack of a strong national carrier resulted in many tourism routes being overtaken by European airlines, but growth in the sector during the 1980s and 1990s saw that 26% of the market share on intercontinental flights were run by Africans.[202] In Latin America and the Caribbean, growth in the tourism sector through the 1990s, led to dramatic expansion of the civil aviation sector, with many countries seeing airport expansions.[203] In military services, women's roles increased during the period in North America, Europe and Asia.[204]

In 1980, Lynn Rippelmeyer of the U.S. became the first woman to fly a Boeing 747 and four years later became the first woman to serve as captain on the craft.[205][206] That same year, Olive Ann Beech was awarded the Wright Brothers Memorial Trophy from the U.S. National Aeronautic Association, for aircraft manufacturing.[207] In 1981, Mary Crawford became the first women's flight officer in the United States Navy[208] and that same year Yichida Ndlovu would earn the first civilian female pilot's license in Zambia.[209] Unable to join the British Royal Air Force or local cadet forces, Elizabeth Jennings Clark of St. Lucia found a private scholarship program to offset the high-cost of training. She became the first female pilot for LIAT when she finished her training in 1983.[210] That same year, Charlotte Larson and Deanne Schulman made history when Larson became the first woman to captain a smoke jumper aircraft and Schulman became the first woman qualified as a smoke jumper.[208]

In Canada the Air Force started a trial program for women pilots in 1979. Dee Brasseur was one of the four selected and in 1988 became one of the two first women in the world to fly the F-18 jet fighter. Khatool Mohammadzai became the first Afghan woman paratrooper in 1984,[211] the same year that Beverly Burns first served as captain on a Boeing 747 for a cross-country trip.[208] In 1986, Rebecca Mpagi joined Uganda's National Resistance Army as its first woman pilot. She would continue to rise in the ranks until by 2008, Mpagi was a Lieutenant Colonel, serving as the head of women affairs for the Uganda People's Defence Force.[212] In 1987, British Airlines hired their first woman pilot, Lynne Barton.[170] and that same year Erma Johnson became the first black and first woman chair of the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport's Board of Directors.[213] Sakhile Nyoni , a Zimbabwean woman, became the first woman pilot in Botswana in 1988.[214] The following year the Afghan Air Force admitted Latifa Nabizada and her sister, Laliuma, as the first women to train at the military flight school.[215] The sisters would graduate from helicopter school in 1991 becoming the first women Afghani pilots.[216] Canadians Deanne Brasseur and Jane Foster were the first women to fly military aircraft in Canada in 1989.[217]

Although five women officers had qualified as Royal Air Force (RAF) pilots in the 1950s, the RAF did not allow women to pursue a career in flying until Julie Ann Gibson and Sally Cox become the RAF's first career pilots in 1990.[170] On July 31 of 1991, the United States Senate lifted the ban on military women flying in combat.[218] By 1998, US military women were flying combat missions from aircraft carriers.[219] In 1992, the first female helicopter pilot to fly in Antarctica was a military officer, Judy Chesser Coffman, of the United States Navy.[220] That same year, Lt. Kelly J. Franke of the United States Navy was the first woman pilot to be awarded the Naval Helicopter Association Pilot of the Year Award.[221] Lt. Franke flew 105 support missions with HSC-2's Desert Ducks detachment in Bahrain and was cited for extraordinary aviation achievements for 664.2 hours of accident free flight hours.[222] While there were many African American women in the US military, it was 1993 before Matice Wright became the first black woman flight officer in the United States Navy.[223] That same year, Nina Tapula became the first woman military pilot of Zambia.[209][224] Harita Kaur Deol became the first female solo pilot in the Indian Air Force , in September 1994, flying an Avro HS-748 at the age of 22.[225][226] Chipo Matimba became the first woman to complete the Air Force of Zimbabwe 's pilot training course in 1996.[227] On December 17, 1998 Kendra Williams was credited as the first woman pilot to launch missiles in combat during Operation Desert Fox.[220] In 1999, Caroline Aigle received the French Air Force's fighter pilot wings and was assigned to fly the Mirage 2000-5.[228]

In the civilian sector, Veronica Foy became the first woman pilot of Malawi in 1992 and by the close of the decade would become Malawi's first woman captain.[229] The first black female Mawalian pilot, Felistas Magengo-Mkandawire began flying as first officer for Air Malawi in 1995.[230] In 1993, Aurora Carandang became the first woman captain for Philippine Airlines.[231] Asnath Mahapa, the first black South Africa n woman, became a pilot in 1998,[232] the same year that Nicole Chang Leng became the first woman pilot of the Seychelles.[233] In November 1998, M'Lis Ward became the first African American woman to captain for a major U.S. commercial airline, United Airlines.[234][199] Also in 1998, Barbara Cassani became CEO of the British airline Go, becoming the first female CEO of a commercial airline.[235]

In 1998, Aysha Alhameli of the United Arab Emirates became the first Emirati female pilot.[236]

More organizations to support women in aviation careers were formed. The Ninety-Nines (the 99s) established the Amelia Earhart Memorial Scholarship Fund in 1940 to honor her memory and perpetuate her ideals and love of flying. From a single scholarship of $125 in 1941, the annual Amelia Earhart Memorial Scholarship Fund has provided over $12 million in scholarships to women from around the world to advance and succeed in aviation and aerospace. Women in Aviation International (WAI) formed in 1990 and formalized the organization in 1994.[237][238] WAI went on to establish the Pioneer Hall of Fame to honor women in aviation who had made special contributions to the field.[239] In 1995, the Federation of European Women Pilots (FEWP) was founded in Rome.[240] and two years later the Association for Women in Aviation Maintenance (AWAM) was formed.[241]

Notable influential profiles and figures in the aviation industry

Over the years since the beginning of the twentieth century, there have been many remarkable moments by women in the aviation industry. However, few were pioneers, and their influence and impact were huge, paving the way for more women to be involved in the different aspects of the aviation industry.

Harriet Quimby – 1875 to 1912

A celebrated pioneer in the United States, Quimby was adventurous and encouraged more women to join the aviation industry. Through her weekly articles in various magazines, she challenged women, and through her visions of airlines to ferry people and scheduled air routes, she made a huge contribution towards the growth and the development of the aviation industry.[242] She warned those who flew aircraft on the dangers of being overconfident and emphasized on the importance of observing safety while piloting . Taught how to fly by John Moisant, Quimby was the first woman to fly across the English Channel.[243] As a contributing journalist in magazines, she shared her experiences and the lessons she learned while piloting. In one of her articles entitled 'Aviation as a Feminine Sport' Quimby noted that there was no reason as to why women would not be as confident as their male counterparts.[244] She added that as long as a person observed maximum care, they would not cause any accidents. Quimby had strong belief in the aviation industry of the United States and encouraged more women to take on the air .

Nancy Harkness Love – 1914 to 1976

Born in February 1914, Nancy played an instrumental role in the acceptance of women, both as career and military pilots. At the age of 16 years, with only 15 hours of solo time, Nancy flew a plane from Boston to Poughkeepsie, New York, where the weather changed.[245] She did not know how to read the compass, and with the gauge broken, had to land the plane . She safely landed the plane, an event that would mark her 40-year career in the aviation industry. After earning Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA) instrument rating and a seaplane rating in 1940, Nancy, alongside other 32 pilots, were tasked with flying American airplanes to Canada, from where they would be shipped to France.[246] At the age of 28, she was appointed as the Director of the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron, WAFS, an organization of women who tested aircraft, ferried aircraft and trained other pilots on how to fly aircraft.[247] This WAFS organization played a pivotal role in the integration of women pilots to the military. Under her command, women flew every type of military aircraft. In addition, through her firm belief that women could still co-exist with men and take on non-traditional roles, more doors were opened for more women in the aviation industry .

Geraldine (Jerrie) Cobb – 1931 to 2019

Born to a commercial pilot in 1931, Jerrie Cobb was the first woman to qualify to go into space. Through the help of her father and football coach, who was a flight instructor and owned a plane, Jerrie learned how to fly, and by the time of her birthday at 17, she got a private pilot's license.[248] Through her savings, which she made while playing softball at semi-professional level, she bought her aircraft, a war surplus Fairchild PT-23. She would later receive her commercial pilot license at the age of 18, permitting her to fly professionally. Jerrie later joined the Lovelace Foundation, where she passed all 75 Mercury astronaut tests.[249] After further tests, Jerry, among the other 11 astronaut candidates were chosen for Project Mercury. Even though she would later be dropped based on lacking jet piloting experience, her contribution to the aviation industry-inspired many other women to join the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the aviation industry in general.[250]

Current trends in the aviation industry regarding women

Today women's participation in the aviation sector remains low. As of December 2019, just 5.4% (25,485 out of 466,900) of all certified civilian pilots (private and commercial) in the United States were women. In December 1980, there were 26,896 female certified civilian pilots in the United States.[251] As of December 2020, the percentage of female civilian pilots (private and commercial in Canada is 8.15%.[251] Canada has seen an increase to 18% of women in Royal Canadian Air Force jobs.[252] The global average was 3%.[253]

Overall, in 2008, there were only 16% of women working in the manufacturing of aircraft and spacecraft.[254] Women who work as aerospace engineers made up only 25% in the field in 2014.[255] Women make up less than 6% of senior executive level positions in airline companies, as of 2015.[256] Pakistani pilot Ayesha Farooq was the first female fighter pilot for the Pakistan Air Force . At least 19 women became pilots in the air force in the decade from 2003.[257] India has been very successful at recruiting women to pilot commercial airliners. In 2014, women made up 11.6% of pilots. Women credit the extended family support systems that exist which help them balance family and career.[253] By 2012, China's PLAAF had trained more than 300 female pilots and over 200 auxiliary air personnel.[145] Large numbers have been trained to fly China's most advanced combat jets, including the J-10.[258] In 2016, Wang Zheng (Julie Wang), now a Silver Airways captain, became the first Asian woman to fly a global circumnavigation and the first Chinese person to pilot an aircraft solo around the world, marking the emergence of women in China's general aviation sector.[259][260]

In Japan, the first female captain for commercial passenger flights was Ari Fuji, who began flying as captain for JAL Express in July 2010.[261] In terms of tourism-driven growth in the aviation sector, throughout the Asia-Pacific region, there is a shortage of pilots, which is driving gender biases to be pushed aside for women to be hired. Vietnam Airlines, a major carrier in one of fastest-growing aviation markets, has created flight-schedules that allow flexibility to deal with personal demands. EasyJet provides scholarships for women pilots to help offset the high cost of training and EVA Air has actively recruited candidates from university programs.[262]

In Africa, many of the trained pilots migrate to the Middle East or Asia where opportunities for career advancement and more sophisticated facilities exist. Women Aviators in Africa was founded in 2008 in an attempt to mentor and inspire young women to train in the aviation industry, as estimates for women in the field fall considerably below 6%. Though there is a high level of need across Africa for rural aviation, there is insufficient infrastructure to support expansion. Grass-roots efforts have seen success with training for bush pilots in transport, medical assistance and policing. Efforts are on-going to increase the numbers of women because women are less likely to move to other areas if they as able to find sufficient employment and opportunities in their own communities.[263] As of 2016, seven of the top ten markets in terms of growth-speed of aviation were in Africa.[262] In 2022, Zara Rutherford became the youngest female pilot to fly solo around the world.[264]

Sexism

Women often had to work hard to prove themselves as capable as men in the field. Clare Booth Luce wrote, "Because I am a woman, I must make unusual efforts to succeed. If I fail, no one will say, 'She doesn't have what it takes.' They will say, 'Women don't have what it takes.'"[265] Pioneer aviator, Claude Grahame-White felt that women were "not 'temperamentally suited' to handle the controls of an airplane".[266]

During the first National Women's Air Derby in 1929, women flying the race faced "threats of sabotage and headlines that read, 'Race Should Be Stopped.'"[4] Because flying was considered dangerous, many aircraft manufacturers in the late 1920s hired women as sales representatives and flight demonstrators. "The reasoning was that if a woman could fly an airplane, it really could not be that difficult or dangerous."[267][115]

In 1986, a spokesperson for the Airline Pilot's Association said that the reason there were only two women Boeing 747 captains at the time was "because women in aviation are a relatively recent phenomenon and everything in the airlines industry is done by seniority".[268] In 1927, Marga von Etzdorf became the world's first woman to fly for an airline, Lufthansa. In 1934, however, Helen Richey became the first woman to fly a commercial airliner in the United States of America and went on to quit that job in ten months because the all-male pilot's union would not admit her and she rarely got to fly.[269] Airlines continue to discriminate against women until it became illegal thanks to the Civil Rights movement. In 1969, Jacqueline Dubut was hired by Air Inter and became the first female airline pilot post Civil Rights movement.

Biases toward women's traditional roles with men in the cockpit and women serving beverages and blankets have become ingrained, forcing women who want to fly to struggle with the attitudes of both co-workers and society.[262]

A survey conducted by Mitchell, Krstivics & Vermeulen in 2005 found that many women pilots were either unaware of sexism directed towards them or had not experienced any sexism directly. However, many women believe that more women are experiencing prejudice than are admitting it.[270]

Diversity in the classroom

Even though in history, women faced exclusion from education, the end of the Civil War signified a new era where women were then allowed to attend classes side by side with the men. More recently, the rates of women attending classes and going through education systems have improved significantly. In 1970, 42.3 percent of the undergraduate students were women, a figure which has grown up to 56.1 percent in 2007.[271] This improvement is key, as it signifies that women have the access to education and training programs than ever before.[272] Contextually, women can access the needed aviation training just like their male counterparts. Therefore, it eliminates the basis of women being incapable of handling particular job profiles and not being capable of working in certain capacities. Thus, women ought to have the same opportunities as men, given the abundance of skills and expertise.[273]

Wage inequalities and career advancement

Wage inequality between men and women has not only been a talking point in the aviation industry but also in other industries where women are paid significantly less than men.[274] Despite possessing the same skills, expertise, and experience, women are not paid the same in the industry. In addition to the skewed wage structure, the organization culture in the industry has continually favored men regarding career advancement up the ladder.[275] Few women advance their careers in the aviation industry as many top positions are held by men. Women have faced a tough time, climbing from the bottom of the ladder up, while men have seamlessly and without a struggle, spend less time at the lower tiers of the career ladder before assuming top positions.[276] In recent attempts to lessen the barrier between men and women in the aviation field programs to help even the playing field have become more abundant. Programs such as A-WING, a program run by over 60 volunteers aims to teach more young women about the aviation job opportunities. The organization is funded through donations which are used to produce educational materials, create speaking and networking opportunities and enable attendance at job fairs and get more women into the aerospace field. Their goal is to increase women in the aerospace job field by 25% by 2025, a goal they call "25 by 25". Programs like these are becoming more prominent in modern society to help with the inequalities in career advancement for women in aviation.[277]

Solutions to gender

Affirmative action

Previous studies demonstrate that affirmative action has compelled women to develop their careers as pilots. It has motivated women to take up the challenges and enter the male-dominated occupation.[278] Following the success of this initiative thus far, albeit unsatisfactorily, it is important that it is continuously implemented to make it easy for women to enter in the aviation industry and progress up the career ladder up to the top management positions. A positive attitude and a change of culture in the aviation industry are needed if men will change their perspective regarding the involvement of women in the aviation industry.[279]

Funding initiatives

Even though the tuition fees for tertiary institutions is not analyzed in this study, receiving the required training and knowledge requires a substantial financial investment. An extensive research found that these tuition and training fees are paid by either parent, the students, or through loans.[280] Given the level of high fees paid during the training, and considering the low incomes paid to women at the start of their careers, it is important that they incentivized in their studies and training.[281] Given the high costs of qualifications, the costly nature of the relevant licenses, and the time consumed, many aviation students end up discontinuing their studies. An increasing number of women scholarships since the 1980s had no impact on the number of women in the industry.

Cultural evolution

Attitudes, stereotypes, and prejudices are embedded in culture and have played a significant role in inequality in the aviation industry. It, therefore, important that men are educated on the impact of these attitudes and prejudices against women. They have to be educated on how their behavior affects pilots and why it is important to evolve the culture in the aviation industry.[282] Having an understanding of the impacts of these attitudes helps in forging great relationships and interactions amongst the diverse flight crews. Women also need to be encouraged to take up these careers to address the underlying problem where women have previously been discouraged from pursuing a professional career in aviation.[283]

See also

- Timeline of women in aviation

- List of women aviators

- Women of Aviation Worldwide Week

- Women in Aviation, International

- Ninety-Nines

References

Citations

- ↑ Smithsonian Air and Space Museum 2013.

- ↑ Dall'Acqua 1986, p. 1.

- ↑ Olsen 2016.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gant 2001, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Goyer 2012.

- ↑ Jessen 2002, p. xi.

- ↑ Sinclair 2012, p. 179.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Centennial of Women Pilots 2009.

- ↑ Holmes 2013, pp. 4–6.

- ↑ Walsh 1913, p. 12.

- ↑ Ruiz & Korrol 2006, p. 188.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Remington 2006.

- ↑ The New York Times 1909.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Branson 2010, p. 110–111.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Parachute History 2001.

- ↑ Berghaus 2009, p. 9.

- ↑ Aldrich 2015.

- ↑ Wright Brothers Aeroplane Company 2014, p. 3.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Women in Aviation International 2003.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Wright Brothers Aeroplane Company 2013.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 The World Magazine 1909.

- ↑ The Oregon Daily Journal 1909, p. 34.

- ↑ Harrisburg Daily Independent 1908, p. 1.

- ↑ Gabrielli 2003.

- ↑ St. Louis Post-Dispatch 1909, p. 6.

- ↑ Crouch 2003, p. 120.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, p. 277.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, p. 70.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, p. 78.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Air Ambulance International 2013.

- ↑ Dumoulin & Feuillen 2005.

- ↑ Cochrane & Ramirez 2016.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, pp. 204–205.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, pp. 215, 219.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 The Pittsburg Daily Headlight 1912, p. 8.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, pp. 220–225.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, p. 226.

- ↑ Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum 2016.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, p. 233.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, p. 164.

- ↑ Cochrane & Ramirez 2014.

- ↑ Gribanov 2013, p. 435.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, p. 91.

- ↑ Flight 11 Nov. 1911

- ↑ Lebow 2002, p. 69.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, p. 77.

- ↑ Lam 2004.

- ↑ Hartmann 2015, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Lanza 2013, pp. 110–115.

- ↑ Marcu 2009.

- ↑ Zakharov 1988, pp. 37–49.

- ↑ South African Power Flying Association 2010.

- ↑ Judge 2015, p. 141.

- ↑ Judge 2012, pp. 163–164, 168.

- ↑ Smithsonian National Postal Museum 2004b.

- ↑ Smithsonian National Postal Museum 2004a.

- ↑ Winged Victory 2006, p. 1910s.

- ↑ Grant 2009.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, p. 86.

- ↑ Branson 2010, p. 108.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 Folstad 2012.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 The Brainerd Daily Dispatch 1921, p. 1.

- ↑ Welshimer 1930, p. 8.

- ↑ Wampler 1932.

- ↑ Sherman 2008.

- ↑ The Detroit Free Press 1920, p. 5.

- ↑ National Aviation Hall of Fame 2006.

- ↑ The Gazette 1921, p. 3.

- ↑ Kochkina 2015.

- ↑ Pringle 1922.

- ↑ Nakamura 2000.

- ↑ Jang Jin Young 2005.

- ↑ Yang & Wu 2006.

- ↑ Centennial of Women Pilots: Etzdorf 2015.

- ↑ Lufthansa 2013.

- ↑ Bednarek & Bednarek 2003, p. 48–49.

- ↑ Gibson 2013, pp. 136–137.

- ↑ Centennial of Women Pilots: Barnes 2015.

- ↑ Jessen 1999.

- ↑ Air Ambulance International n.d.

- ↑ Lebow 2002, p. 42–43.

- ↑ Sissons 2007.

- ↑ The new biographical dictionary of Scottish women. Elizabeth Ewan. Edinburgh. 2018. ISBN 978-1-4744-3629-8. OCLC 1057237368. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1057237368.

- ↑ Hollander, Jessen & West 1996, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Bednarek & Bednarek 2003, p. 80.

- ↑ Latson 2015.

- ↑ Molotsky 1985.

- ↑ BBC 2015.

- ↑ Pottle, Mark (2004). "Bruce [née Petre, Mildred Mary (1895–1990), motorist and aviator"] (in en). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/63962. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-63962. Retrieved 2022-08-09. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Strassmann 2008, p. [page needed].

- ↑ "Sywell Aerodrome History". https://www.sywellaerodrome.co.uk/about-us/aerodrome-history/.

- ↑ (in en) Flight International. IPC Transport Press Limited. July 1931. https://books.google.com/books?id=8W4PAAAAIAAJ&q=MOLLY+OLNEY.

- ↑ "Aerodrome Activities". The Aeroplane 43. 1932. https://books.google.com/books?id=_3UfAQAAMAAJ&q=MOLLY+OLNEY.

- ↑ Crellin 2014.

- ↑ Crouch 2003, p. 282.

- ↑ Alden 1932, p. 17.

- ↑ Dall'Acqua 1986, p. 2.

- ↑ Habib 2014.

- ↑ Markwick & Cardona 2012, p. 37.

- ↑ Centennial of Women Pilots: Raskova 2015.

- ↑ Strebe 2007, p. 16.

- ↑ Merry 2010, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Ferraro 2008.

- ↑ Ying 2012.

- ↑ Monash University 2009.

- ↑ Lehmkuhl 2008.

- ↑ Monash University 2002.

- ↑ Kulkarni 2009.

- ↑ Ramachandran 2006.

- ↑ The AOPA Pilot 1962, p. 70. "Hanna Reitsch of Frankfurt, Germany, who was the world's first helicopter pilot—man or woman ..."

- ↑ Tucker 2016, p. 1396.

- ↑ Sofroniou 2013, p. 198.

- ↑ Kirkland 2013, p. 85.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 "Bendix Trophy". http://www.air-racing-history.com/Between_the_wars_2_.html.

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Crouch 2003, p. 308–309.

- ↑ "First Women to win Bendix Transcontinental Speed Race 1936" (in en). 2014-08-02. https://firstflight.org/first-women-to-win-bendix-transcontinental-speed-race-1936/.

- ↑ Altınay 2001.

- ↑ Bird & Botes 1982.

- ↑ Best n.d., p. 49.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 120.2 120.3 Texas Women's University 2013.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Martin 1993.

- ↑ Federal Aviation Administration n.d.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Douglas 2004, p. 135.

- ↑ Shetterly 2016, pp. 7, 11–12.

- ↑ Coetzee 2015.

- ↑ Salt 2015, p. 108.

- ↑ Cipalla 1987.

- ↑ "ATA Personnel". https://archive.atamuseum.org/personnel.php.

- ↑ "Ida Veldhuyzen van Zanten - 08 - de Vliegende Hollander" (in nl-NL). https://magazines.defensie.nl/vliegendehollander/2015/05/ida-veldhuyzen-van-zanten.

- ↑ Beton Delègue 2011.

- ↑ March 2016.

- ↑ Lee 2008, p. 233.

- ↑ 오마이뉴스 2004.

- ↑ Garber 2013.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 Martin 2013.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 All About Military 2010.

- ↑ Noggle 2001, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Jackson 2003, p. 57.

- ↑ 139.0 139.1 Reis 2013.

- ↑ Rodrigues & de Lima 2009, p. 2.

- ↑ The Ottawa Journal 1951, p. 3.

- ↑ Pidduck 2006.

- ↑ "Wendy Yawching". St Augustine, Trinidad: National Institute of Higher Education, Research, Science and Technology. http://www.niherst.gov.tt/icons/women-in-science/wendy-yawching.html.

- ↑ Wallace 2015.

- ↑ 145.0 145.1 Allen & Kelly 2012.

- ↑ Gordon 2001, p. 66.

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 147.2 Smalling 1990, p. 50.

- ↑ Douglas 2004, p. 131.

- ↑ Douglas 2004, p. 133.

- ↑ Hwang 2013.

- ↑ Gollob 2005.

- ↑ Bridges & Neal-Smith 2014, p. 168.

- ↑ Weitekamp 2005, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Shah 2015.

- ↑ Brock University 2006.

- ↑ Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum 2007.

- ↑ Brownlee 2013.

- ↑ Brown 1995.

- ↑ 159.0 159.1 Southern African Women in Aviation and Aerospace 2012.

- ↑ 160.0 160.1 République Tunisienne Ministère du Transport 2013.

- ↑ 161.0 161.1 The Jamaica Observer 2010.

- ↑ 162.0 162.1 Somali Aviation Resource Center 2013.

- ↑ 163.0 163.1 McKenzie 2013.

- ↑ 164.0 164.1 The National Mirror 2014.

- ↑ 165.0 165.1 Singapore Council of Women's Organisations 2015.

- ↑ 166.0 166.1 Handy 2014.

- ↑ Variety 1962.

- ↑ Barry 2006.

- ↑ Bridges & Neal-Smith 2014, pp. 168–169.

- ↑ 170.0 170.1 170.2 Gough-Cooper 2013.

- ↑ Guyana Chronicle 2014.

- ↑ Tadias Magazine 2010.

- ↑ "Auriol, Jacqueline (1917—) | Encyclopedia.com". https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/auriol-jacqueline-1917.

- ↑ Weitekamp 2004a.

- ↑ Sharp 2013.

- ↑ Knox 2013.

- ↑ Deedes 2001.

- ↑ Bouraia 2002.

- ↑ McLean 2001.

- ↑ Getline 2005.

- ↑ Turner 2011, p. 55.

- ↑ Skogen 2014, p. 16.

- ↑ Anderson 2002.

- ↑ Charlton 1973.

- ↑ Ganson 2015.

- ↑ The Index-Journal 1974, p. 15.

- ↑ 188.0 188.1 188.2 The Ninety Nines n.d.

- ↑ Parrack 2006.

- ↑ Aero Club of New England 2011.

- ↑ Swopes 2015.

- ↑ Garwood 2014.

- ↑ BBC 2004.

- ↑ Grainger 2013.

- ↑ Roberts 2015.

- ↑ San Diego Air & Space Museum n.d.

- ↑ Tribune 242 2012.

- ↑ Ho 1995.

- ↑ 199.0 199.1 Horton 2000, p. 14.

- ↑ American Business Reference Inc. (1977)[full citation needed]

- ↑ Hansen & Oster, Jr. 1997, pp. 117–119.

- ↑ Otieno 2013.

- ↑ West 2001, pp. 307, 401, 419, 526, 699.

- ↑ Becraft 1990.

- ↑ Saathoff 2013.

- ↑ Gibson 2013, p. 145.

- ↑ Farney 2010, pp. 172–174.

- ↑ 208.0 208.1 208.2 Gant 2001, p. 12.

- ↑ 209.0 209.1 GlObserver 2013.

- ↑ Aimable 2014.

- ↑ BBC News Magazine 2013.

- ↑ Okwera 2012.

- ↑ Smith, Bracks & Wynn 2015, p. 473.

- ↑ Bulawayo 24 2011.

- ↑ Sara 2013.

- ↑ Moreau & Yousafzai 2013.

- ↑ Monroe 2004.

- ↑ Schmitt 1991.

- ↑ Colonial Williamsburg Foundation 2008.

- ↑ Bogino 1992.

- ↑ Flying 1992, p. 34.

- ↑ Douglas 2004, p. 251.

- ↑ MiCampus Magazine 2016.

- ↑ Ministry of Information and Broadcasting 1998, p. 686.

- ↑ The Indian Express 2008.

- ↑ Girls High School 2015.

- ↑ Catholic News Agency 2007.

- ↑ Twea 2016.

- ↑ Nyasa Times 2016.

- ↑ Philippine Airlines 2015.

- ↑ Humayan, Sealy & Parke 2016.

- ↑ Kreol Magazine 2011.

- ↑ Hughes 2000, pp. 120–124.

- ↑ "Barbara Cassani '82". Vista (Mount Holyoke College) 4 (3). Spring 2000. https://www.mtholyoke.edu/offices/comm/vista/0002/cassani.shtml. Retrieved 2021-01-14.

- ↑ "Aysha Alhameli". Delegation of the United Arab Emirates at ICAO. https://www.icao.int/Meetings/iwaf2018/Documents/Biographies/Capt.%20Aysha%20Alhameli%20%20Biography.pdf.

- ↑ Flying 1996, p. 44.

- ↑ Flying 1997, p. 35.

- ↑ Flying 2000, p. 44.

- ↑ British Women Pilots' Association Newsletter 2011, p. 19.

- ↑ Florida Department of Transportation 1996.

- ↑ Kerr 2016, p. [page needed].

- ↑ Brown 1997, p. [page needed].

- ↑ McLoone 2000, p. [page needed].

- ↑ Douglas 2010.

- ↑ Weatherford 2009, p. [page needed].

- ↑ Rickman 2009, p. [page needed].

- ↑ Ackmann 2003, p. [page needed].

- ↑ Brady 2000, p. [page needed].

- ↑ Weitekamp 2004, p. [page needed].

- ↑ 251.0 251.1 "Closing the gender gap in the air and space industry | Institute for Women Of Aviation Worldwide (iWOAW)" (in en-US). 2017-11-18. https://www.iwoaw.org/.

- ↑ Parker 2016, pp. 24–27.

- ↑ 253.0 253.1 Sinha 2014.

- ↑ Poole 2008.

- ↑ Marcus 2014.

- ↑ Centre for Aviation 2015.

- ↑ Ynetnews 2013.

- ↑ Monster Worldwide 2012.

- ↑ Sina Travel 2016.

- ↑ Yahoo! News 2016.

- ↑ Wang 2010.

- ↑ 262.0 262.1 262.2 Boudreau & Nguyen 2016.

- ↑ Grant 2011.

- ↑ "Teenage pilot Zara Rutherford completes solo round-world record". BBC News. 20 January 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-hampshire-59899980.

- ↑ Gibson 2013, p. 2.

- ↑ Crouch 2003, p. 308.

- ↑ Bednarek & Bednarek 2003, p. 49.

- ↑ Dean 1986, pp. 1–4.

- ↑ Holden 2001.

- ↑ Civil Aviation Safety Authority Australia 2015.

- ↑ Williams 2019.

- ↑ Parvazian, Gill & Chiera 2017.

- ↑ Ison 2010.

- ↑ Morris 2016.

- ↑ Chapman & Benis 2017.

- ↑ Härkönen, Manzoni & Bihagen 2016.

- ↑ "An Aviation Executive is Trying to Level The Playing Field" (in en-US). 2022-03-25. https://www.flyingmag.com/an-aviation-executive-is-trying-to-level-the-playing-field/.

- ↑ Ryan & Branscombe 2013.

- ↑ Tinoco & Rivera 2017.

- ↑ OECD 2015.

- ↑ Klugman et al. 2014.

- ↑ Heilman 2001.

- ↑ Neal-Smith & Cockburn 2009.

Sources

- Ackmann, Martha (2003). The Mercury 13: the untold story of thirteen American women and the dream of space flight (1st ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 0-375-50744-2. OCLC 51266180. https://archive.org/details/mercury13untolds00ackm.

- Aimable, Anselma (May 27, 2014). "Did You Know: St. Lucia's first female pilot". Castries, St. Lucia. http://www.stlucianewsonline.com/did-you-know-st-lucias-first-female-pilot/.

- Alden, Alice (12 August 1932). "Give Woman Her Place in the Air". The Evening News (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania). https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7683500/.

- Aldrich, Nancy W. (2015). "Who Was First?: "Pottelsberghe, Peltier, or Berg"". Lakeland, Florida. http://20thcenturyaviationmagazine.com/o-capt-nancy-aldrich/who-was-first/.

- Allen, Kenneth; Kelly, Emma (June 22, 2012). "China's Air Force Female Aviators: Sixty Years of Excellence (1952–2012)". China Brief (Washington, DC: Jamestown Foundation) 12 (12). https://jamestown.org/program/chinas-air-force-female-aviators-sixty-years-of-excellence-1952-2012/. Retrieved 18 December 2016.

- Altınay, Ayşe Gül (25 March 2001). "Dünyanın İlk Kadın Savaş Pilotu: Gökçen" (in tr). Bianet. Istanbul, Turkey: BİA Haber Merkezi. http://bianet.org/bianet/siyaset/1361-dunyanin-ilk-kadin-savas-pilotu-gokcen.

- Anderson, Joel (March 26, 2002). "Woman retiring after 26 years with American Airlines". AP. Plainview, Texas: The Plainview Herald. http://www.myplainview.com/news/article/Woman-retiring-after-26-years-with-American-8801091.php.

- Barbera, Jonathon (2005). Agent of the Gentle Empire with New Technology. New York, NY: iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-34719-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=6H45aod2hI8C&pg=PA37.

- Barry, Kathleen M. (2006). "Timeline of Flight Attendants' Fight Against Discrimination". Towson, Maryland. http://femininityinflight.com/activism.html.

- Becraft, Carolyn (1990). "Facts About Women in the Military, 1980–1990". Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: Carnegie Mellon University Women's Center. http://feminism.eserver.org/workplace/professions/women-in-the-military.txt.

- Bednarek, Janet R. Daly; Bednarek, Michael H. (2003). Dreams of Flight: General Aviation in the United States. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 1-58544-257-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=x0uLSdn_hFUC&q=women%20in%20aviation%20history&pg=PA49.

- Berghaus, Günter (2009). Futurism and the Technological Imagination. Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-420-2747-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=bA4zta2tgcUC&pg=PA9.

- Best, Liz (n.d.). "Patricia Malone helps airline pilots get you there". unnamed newspaper clipping. p. 49. http://site.mothermalone.com/uploads/GAHOF_Nomination.pdf.

- Beton Delègue, Elisabeth (20 June 2011). "Discurso de la Embajadora (Condecoración de Margot Duhalde)" (in es). Santiago, Chile: Embajada de Francia en Santiago de Chile. http://www.ambafrance-cl.org/Discurso-de-la-Embajadora,1031.

- Bird, Marjorie Egerton; Botes, Molly (June 1982). "Flying High: The Story of the Women's Auxiliary Air Force 1939–1945". Military History Journal (Kengray, Johannesburg, South Africa: The South African Military History Society) 5 (5). http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol055mb.html. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- Boudreau, John; Nguyen, Giang (April 3, 2016). "Travel Boom Forces Asia's Airlines to Seek More Women Pilots". Bloomberg Businessweek (New York City, New York). https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-04-03/female-top-guns-wanted-to-solve-pilot-crisis-at-asia-s-airlines. Retrieved 29 December 2016.

- Bouraia, Marina (May–June 2002). "Galina Gavrilovna Korchuganova". International Women Pilots Magazine 30 (3): 20–21. https://www.ninety-nines.org/pdf/newsmagazine/20040506.pdf.

- Brady, Tim (2000). The American aviation experience: a history. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-2325-7. OCLC 43050136.

- Branson, Richard (2010). Reach for the Skies: Ballooning, Birdmen, and Blasting Into Space. New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-1-61723-003-5. https://archive.org/details/isbn_9781617230035.

- Bridges, Donna; Neal-Smith, Jane (2014). Absent Aviators: Gender Issues in Aviation. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-4724-3338-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=51XACwAAQBAJ&pg=PR4.

- Brown, Ruth (Autumn 1995). "Racism and immigration in Britain". International Socialism Journal (London, England: Socialist Workers Party) (68). ISSN 1754-4653. http://pubs.socialistreviewindex.org.uk/isj68/brown.htm. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- Brown, Sterling (1997). First lady of the air: the Harriet Quimby story (1st ed.). Greensboro, NC: Tudor Publishers. ISBN 0-936389-49-4. OCLC 37201345.

- Brownlee, John (5 December 2013). "What It Was Really Like To Fly During The Golden Age Of Travel". New York, New York. https://www.fastcodesign.com/3022215/terminal-velocity/what-it-was-really-like-to-fly-during-the-golden-age-of-travel.

- Chapman, Stephen J.; Benis, Nicole (November 2017). "Ceteris non paribus: The intersectionality of gender, race, and region in the gender wage gap". Women's Studies International Forum 65: 78–86. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2017.10.001.

- Carsenat, Elian; Rossini, Elena (August 5, 2014). "Airline Pilots: how many women in The Airman Directory?". http://gendergapgrader.com/studies/airline-pilots/.

- Charlton, Linda (10 June 1973). "Women Pilots". The New York Times (New York City, New York). https://www.nytimes.com/1973/06/10/archives/fly-me-means-fly-me-women-pilots-trends.html?_r=0.

- Cipalla, Rita (March 29, 1987). "Sky's No Limit". The Chicago Tribune. Smithsonian News Service (Chicago, Illinois). http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1987-03-29/features/8701240874_1_helicopter-pilot-whirly-girls-air-force-reserve.

- Cochrane, D.; Ramirez, P. (2016). "Helene Dutrieu". Washington, DC: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. https://airandspace.si.edu/explore-and-learn/topics/women-in-aviation/dutrieu.cfm.

- Cochrane, D.; Ramirez, P. (2014). "Matilde Moisant". Washington, DC: Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum. http://airandspace.si.edu/explore-and-learn/topics/women-in-aviation/Moisant.cfm.

- Coetzee, Anchen (May 6, 2015). "Local female pilot leaves a lasting legacy". Barberton, Mpumalanga, South Africa: Barberton Times. http://barbertontimes.co.za/193326/local-female-pilot-leaves-a-lasting-legacy/.

- Crellin, Evelyn (2014-04-11). "Antonie Strassmann – German Movie Star, American Entrepreneur, Cosmopolitan Pilot". National Air and Space Museum. https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/antonie-strassmann-german-movie-star-american-entrepreneur-cosmopolitan-pilot.

- Crouch, Tom D. (2003). Wings: A History of Aviation from Kites to the Space Age. New York, New York: W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-05767-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=cXQmUf-JtNkC&pg=PR4.

- Dall'Acqua, Joyce (23 March 1986). "Women Pilots Built Their Careers on Fear of Flying: Companies Hired Them to Prove Safety of Air Travel". Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California).

- Dean, Paul (2 February 1986). "More and More Women Are Finding the Skies Friendly in the Air Force". Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California): pp. 1–4. https://articles.latimes.com/1986-02-02/news/vw-3624_1_u-s-air-force.

- Deedes, W F (3 January 2001). "Mama Daktari's high-flying life of adventure". The Daily Telegraph (London, England). https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/kenya/1313009/Mama-Daktaris-high-flying-life-of-adventure.html.

- Douglas, Deborah G. (2004). American Women and Flight Since 1940. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 0-8131-9073-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=c89LN66l9M4C&pg=PR4.

- Douglas, Deborah G. (2010). "Nancy Batson Crews: Alabama's First Lady of Flight (review)". Alabama Review 63 (4): 298–299. doi:10.1353/ala.2010.0026. ISSN 2166-9961.

- Dumoulin, Alphonse; Feuillen, Robert (2005). "Hélène Dutrieu, première aviatrice belge, pionnière de l'aviation féminine, membre d'honneur à titre posthume de la Société royale" (in fr). Brussels, Belgium: Société royale des Pionniers et Anciens de l'Aviation belge. http://www.vieillestiges.be/fr/rememberbook/contents/31.

- Farney, Dennis (2010). The Barnstormer and the Lady. Kansas City, Missouri: Rockhill Books. ISBN 978-1-935362-69-2.

- Ferraro, Jordan (2008). "Lee Ya-Ching Papers". Chantilly, Virginia: National Air and Space Museum Archives Division. http://sova.si.edu/record/NASM.2008.0009?q=*&s=0&n=10.

- Folstad, Hartley (2012). "Wingwalking History". Homestead, Florida. http://www.silverwingswingwalking.com/resource_zone.html.

- Gabrielli, Betty (15 December 2003). "The Wright Stuff". Oberlin, Ohio: Oberlin College. http://www.oberlin.edu/news-info/03dec/katharineWright.html.

- Ganson, Barbara (February 21, 2015). "U.S. Women of Military Aviation History Since World War I". Vancouver, Canada: Institute for Women Of Aviation Worldwide. http://www.womenofaviationweek.org/u-s-women-of-military-aviation-history-since-world-war-i/.