Engineering:Groundwater banking

Groundwater banking is a water management mechanism designed to increase water supply reliability.[1] Groundwater can be created by using dewatered aquifer space to store water during the years when there is abundant rainfall. It can then be pumped and used during years that do not have a surplus of water.[1] People can manage the use of groundwater to benefit society through the purchasing and selling of these groundwater rights. The surface water should be used first, and then the groundwater will be used when there is not enough surface water to meet demand.[2] The groundwater will reduce the risk of relying on surface water and will maximize expected income.[2] There are regulatory storage-type aquifer recovery and storage systems which when water is injected into it gives the right to withdraw the water later on.[2] Groundwater banking has been implemented into semi-arid and arid southwestern United States because this is where there is the most need for extra water.[2] The overall goal is to transfer water from low-value to high-value uses by bringing buyers and sellers together.[2]

Groundwater storage concepts

The bank is an aquifer used as an underground storage tank, and the recharge of water causes an increase in the volume of water stored in the aquifer to have increasing water levels.[2] In the case of a withdrawal there would be a decrease in water levels.[2] The amount of water depends also on a couple of other factors including groundwater pumping by other users, leakage, and natural recharge.[2] The recharge of water by land application or injection increases the volume of water, and then some of the water will be used at a future time.[2] It can be looked at as inputs of water minus outputs is equal to the change in water storage.[2]

Another aspect is the hydrology which is the difference between dynamic and static response to recharge and abstraction.[2] The water levels will rise or fall in the well during recharge and recovery.[2] Once recharge and recovery stops the water levels return to background levels, and one of the main issues is the change in static water levels after the dynamic response from recharge or recovery disappears.[2]

There can be some technical issues with the aquifer response to manage recharge and recovery.[2] If the aquifer is hydraulically connected to body of water on the surface there are increases in the water table elevation as the result of managed recharge.[2] This could increase the rate of discharge or decrease the amount of induced recharge, and both of these cause water to leave the basin.[2] The recharge and recovery could also affect the lateral and vertical groundwater flow into the aquifer.[2] There is not always a one-to-one correspondence between the volume of water and the change in storage.[2]

Methods

Groundwater banking is accomplished in two ways: through in-lieu and direct recharge.[1] In-lieu recharge is storing water by utilizing surface water "in-lieu" of pumping groundwater, thereby storing an equal amount in the groundwater basin.[1] In-lieu recharge is the renewable surface water used to irrigate the farmland in place of using regular groundwater.[3] This is helping to save more groundwater because the water stays in the aquifer to be used later.[3] Direct recharge is storing water by allowing it to percolate directly to storage in the groundwater basin.[1] With direct recharge it floods an area so that water seeps through the ground to get to the aquifers.[3] The water is then pumped out when there is more of a demand with the use of recovery wells.[3]

Pros and cons

There are some disadvantages to retrieving this groundwater. As groundwater is withdrawn from below the surface, the ground above settles.[4] This settling of land, known as subsidence, can fracture roads and building foundations and can burst water, sewer, and gas lines.[4] This method hasn't been well tested yet, so there could be some negative impacts on the environment. Water is a public resource and this could make water become a private industry.[5]

Groundwater banking can be compared and contrasted to the use of surface reservoirs. Groundwater banking has many advantages over the use of surface reservoirs. The projects do not cost as much to construct and store the same amount, if not more, than the surface reservoirs.[6] The bank will have less of an impact on the environment than a surface reservoir.[6] The water that is in the bank will no longer be exposed to evaporation, but several feet per year of water is lost in the reservoirs.[6] It is more reliable to use when the climate is changing and can respond to seasonal changes better to manage the water than the surface reservoirs.[6]

There are also some disadvantages to groundwater banking over surface reservoirs. There are energy costs to recovering the water and these costs are usually more than the reservoirs.[6] There is also a pumping capacity and when the demands change during the year the productiveness can be limited.[6]

Not all groundwater is used when sold. Some groundwater is being studied for its benefits. Groundwater banking and aquifer storage systems are being explored to control flooding during times of high precipitation.[7]

The groundwater is being traded in many regions. There are trades even in the United States. The city of San Antonio, Texas is the largest city in the United States that relies solely on groundwater for its municipal supply.[7]

Feasibility of groundwater recharge on agricultural land

There have not been many successful trials of groundwater banking on agricultural land since the land is usually privately owned.[8] The owners have to be on board with the practice of groundwater banking knowing what the risks and best practices entail.[8] A study was done to find a Soil Agricultural Groundwater Banking Index (SAGBI) which evaluates soil suitability for the use of groundwater banking in California .[8] There are five factors that determine the feasibility of groundwater recharge on agricultural land: deep percolation, root zone residence time, topography, chemical limitations, and soil surface conditions.[8] The five factors were modeled using United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service (USDA-NRCS) digital soil survey data.[8]

For the deep percolation factor a high rate of water transmission through the soil profile and into the aquifer below is the key to successful groundwater banking.[8] It becomes more important when there is flooding since it could be used as the main water source.[8] It is derived from the saturated hydraulic conductivity of the limiting layer.[8] Saturated hydraulic conductivity measures soil permeability when the soil is saturated.[8]

When looking at root zone residence time factor it was found that a prolonged duration of saturated conditions in the root zone has the possibility to cause damage to perennial crops.[8] If the soil causes a bud break it is more likely that the crop will become damaged.[8] Most crops are not able to withstand long periods of saturated conditions in the root zone.[8] The root zone residence time estimates the likelihood of having good enough drainage within the root zone once water is applied.[8]

The topography of land for spreading water across fields has the best outcome when there is level topography.[8] Level topography works the best because it holds water better on the landscape which allows infiltration across large areas.[8] Infiltration reduces ponding and minimizes erosion by runoff.[8]

The chemical limitations factor is related to the salinity which is a threat to the sustainability of agriculture and groundwater.[8] This factor was determined by electrical conductivity (EC) of the soil which measures the soil salinity.[8] The best soil has the lowest levels of salinity.[8] Soil also has pesticides and nitrate, but it is unable to be evaluated due to the dependency on management history.[8]

The surface condition factor is when banking by flood spreading can change the soil surfaces physical conditions.[8] Infiltrations limits can be caused by quality and depth of water that could lead to the destruction of aggregates, the formation of physical crusts, and compaction.[8] To determine soil condition two factors were examined: soil erosion factor and sodium absorption ratio (SAR).[8]

To determine the feasibility of groundwater banking each of the five factors were assigned a weight to how significant it was, and then a SAGBI score was calculated.[8] The weights were 27.5% deep percolation, 27.5% root zone residence time, 20% topography, 20% chemical limitations, and 5% surface conditions.[8] Of the 17.5 million acres of agricultural land examined only 5 million acres were considered soils with excellent, good, and moderately good suitability.[8]

Agricultural groundwater banking can be associated with financial risk which may cause crop loss, so in the end, the loss may exceed the benefits of water saving.[8] Adoption of this practice would require support to protect growers from risk of crop failure.[8]

Groundwater accounting system

The accounting system tracks the recharge and withdrawals of stored water and it can include a market system to reserve the storage of water.[2] Depositors could earn credits for the recharge of water which can be used later on for the water recovered from the bank.[2] The banking system could then be set up to allow trading of credits.[2] There are several objectives of the water bank accounting system: track water deposits, withdrawals, and to control the amount, timing, and location of withdrawals by the participants.[2] If groundwater is not regulated there is more of a chance for freeriding and overuse.[2] There needs to be sustainability of the system in order to continue with the operation of the system or there would be no point to using it.[2]

The accounting method that will be used is the double-entry accounting method, so every transaction is recorded as a debit and a credit in separate ledger accounts.[2] This also allows for tracking of inventory in asset accounts and claims to inventory in ownership accounts.[2] Deposits happen when more water is stored in an aquifer than there is supposed to be.[2] The recharge of water by a member would be a credit in a member's account and a liability in the bank's account.[2] For the bank to be successful then both ledgers have to be balanced, so the right to water in a member's accounts should be equal to the amount of water that can be recovered from the system.[2] If the right to water is greater than liabilities then the bank is insolvent, and this will become a problem when a drought occurs.[2]

There are some issues that could arise from using this water bank accounting system. These problems were evaluated for the Las Posas Basin groundwater bank and Fox Canyon Groundwater Management Agency (FCGMA) has jurisdiction over the project.[2] FCGMA reported that the accumulation of credits has been increasing for banks.[2] What can happen is the accumulated credits can become greater than the annual abstraction rate.[2] The volume of credits accumulating exceed the amount of water that can be taken out during a short-time period.[2] This will cause a threat to the regional groundwater resource or even depressions in groundwater elevations, land subsidence, and seawater intrusion.[2]

Regulatory framework

The banking systems need regulatory control over the basin to implement the withdrawal rates and to ensure that other participants will not extract too much stored water.[2] The best scenario would be that the bank owner or participants would be the main users to ensure that abstractions are controlled.[2] If this is not the case, then there must be another way to control the number and amount of abstractions happening.[2] It needs to be clear who has priority over stored water, so that when abstractions are constrained it is known who will get the water first.[2] There can be problems when multiple entities have jurisdiction over a project, and this can cause regulatory and organizational challenges.[2] There are some generally accepted rules and also many of the issues are handled through state-specific concepts.[2] One of the main requirements is an action needs to be in place so that the stored water is not being abstracted by other users who are not involved in the system.[2] These frameworks rely on the knowledge of hydrogeology to determine the success of a system, and the systems need to provide benefits to prove it was worth building.[2]

Economics

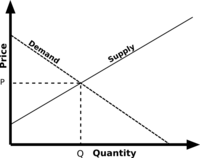

The different projects can become economically efficient by maximizing the benefits of the limited resource (water).[9] To maximize efficiency the users need to find where marginal cost is equal to marginal benefit.[9] It is important for supply to equal demand like in the figure below. The use of water becomes a negative externality when there is rivalry and the property rights are not well-defined.[9] The way to eliminate some of the negative externality is there can be a tax placed on the resource to increase the marginal cost.[9] When they tax the right amount the user will use the resource at the socially acceptable level.[9] The other way to affect the externality is to create a subsidy. A subsidy will increase the marginal benefit in order to get to the socially accepted level of use for the resource.[9]

Water is not a homogeneous commodity for several reasons which include sensitivity to location, time of use, form of the water, and administrative responses.[9] The use of groundwater banking can make water a more homogenous commodity. This can create a market value which will enhance private investment increasing the benefits.[9] It will also align marginal benefit with marginal cost causing the market to come to an economically efficient level.[9]

Water has high transaction costs and create market barriers which devalues the use to society restricting the reallocation of resources.[9] The demand does not change when there is a market barrier so there will be many unpleasant people if they do not get their share of water.[9] If a bank is in the process of being made the removal of market-access barriers can be part of the negotiations, but it is not necessarily the bank itself that is the cause.[9] Groundwater banking could reduce transaction costs because each individual won't have to analyze each transaction.[9]

See also

- Water trading

- Aquifer storage and recovery: storing water in aquifers using wells

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Semitropic Water Storage District. FAQs. <http://www.semitropic.com/GndwtrBankFAQs.htm>.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 2.30 2.31 2.32 2.33 2.34 2.35 2.36 2.37 2.38 2.39 2.40 2.41 2.42 Maliva, Robert G. "Groundwater Banking: Opportunities And Management Challenges." Water Policy 16.1 (2014): 144-156. Academic Search Complete. Web. 18 Nov. 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "Recharge and Facilities". http://www.azwaterbank.gov/Water_Storage/Recharge_and_Facilities.htm.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Archived copy". http://www.ngs.noaa.gov/PUBS_LIB/thePossibilities/Imagine_08-11.pdf.

- ↑ "Groundwater Banking – Water Education Foundation". http://www.watereducation.org/aquapedia/groundwater-banking.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://mavensnotebook.com/the-notebook-file-cabinet/groundwater-banking/.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}] - ↑ 7.0 7.1 http://www.cpo.noaa.gov/sites/cpo/Projects/SARP/CaseStudies/2013/Russian%20River%20Basin%20CA_Case%20Study%20Factsheet_Extreme%20Weather%20Events_2013-2-6v1.pdf [bare URL PDF]

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 8.18 8.19 8.20 8.21 8.22 8.23 8.24 8.25 8.26 8.27 O'Greene, A.T. (April 2015). "Soil suitability index identifies potential areas for groundwater banking on agricultural lands". California Agriculture 69 (2): 75–84. doi:10.3733/ca.v069n02p75. http://calag.ucanr.edu/Archive/?article=ca.v069n02p75.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 Contor, Bryce (August 2009). "Groundwater Banking and the Conjunctive Management of Groundwater and Surface Water in the Upper Snake River Basin of Idaho". Idaho Water Resources Research Institute Technical Completion Report.

External links

|