Unsolved:Orbital (The Culture)

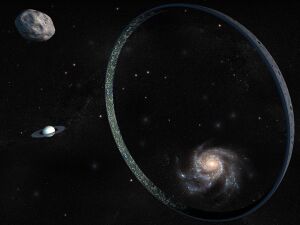

In Iain M. Banks' fictional Culture universe, an Orbital (sometimes also simply called an O or a small ring) is a purpose-built space habitat forming a ring typically around 3 million km (1.9 million miles) in diameter. The rotation of the ring simulates both gravity and a day-night cycle comparable to a planetary body orbiting a star.

Its inhabitants, often numbering many billions,[1][2] live on the inside of the ring, where continent-sized "plates" have been shaped to provide all sorts of natural environments and climates, often with the aim of producing especially spectacular results.

Orbitals first appear in Banks' 1987 novel Consider Phlebas, and again in many later novels in the series.

Introduction

Banks has described Orbitals as looking like "a god's bracelet"[2] hanging in outer space. Orbitals are ribbon-like hoops of a super-strong material reinforced and joined with force fields. Each Orbital possesses a "hub", a station suspended at its rotational centre which houses the Orbital's governing Mind.

An Orbital is a similar concept to Niven's Ringworld, although much smaller than it and does not enclose its primary star within itself, instead orbiting the star in a more conventional manner, making it much more intrinsically stable than a ringworld.[1] It is also similar to the later habitat concept by Bishop, the 1997 "Ring" habitat concept, which is similar although somewhat smaller.

Design

In Banks' Culture novels, many different civilizations are known to use Orbitals sized according to the preferences of the builders; the Culture's Orbitals are approximately 10 million kilometres in circumference, which, together with their rotational speed, creates gravity and day-night cycles to normal Culture standard.[3]:275 To put this another way, with a diameter of 3 million kilometres the orbital completes a full rotation once per standard Culture day to simulate normal Culture gravity via centrifugal force, and as the orbital is itself orbiting a star this in turn gives the seasonal cycle.[4] They have widths varying between one thousand and six thousand kilometres, giving them a surface area of between 20 and 120 times that of the Earth (but comprising significantly less mass).[4]

Orbitals are regarded as highly matter-efficient, providing vastly more usable living space for their constituent mass than primitive arrangements like planets.[5] The Culture therefore prefers to leave planets unterraformed, treating them like wilderness areas.[4]

Interior

The inside of the hoop can be formed to any type of planetary environment, from desert, through ocean, and jungle to glacier. The structure is usually divided into individual 'plates', similar to continents. Though there need be no directly visible indication for the transition from one plate to another, on some Orbitals the border between neighboring plates is marked by an artificially high string of mountains known as a 'bulkhead range'. These also serve to contain the atmosphere in those areas where the Orbital may not yet be complete, with those gaps in the plate ring being bridged only by forcefields.[3]:331

Some plates mimic natural environments very closely, while others are wild exaggerations possible only by advanced matter forming and intricate (but usually hidden) machinery—such as a gigantic river circumnavigating the whole Orbital, which in some regions travels on immense, kilometre-high bridge- or mountain-range-like constructions, and in other regions might act as an immense 'waterslide' for a floating event stadium.

Orbitals spin to mimic the effects of gravity and are sized so that the rate of rotation necessary to produce a comfortable gravity level is approximately equal to one day. In the case of the standard Culture day and gravity, this diameter is around three million kilometres. For such an orbital to reproduce the equivalent to the Earth's gravity (9.8 m/s2 at sea level), whilst maintaining Earth's 24-hour period of rotation, it would need to have a diameter of approximately 3.71 million kilometres, and spinning at 486,000 km/hr. By tilting the axis of the Orbital relative to its orbit around a star a convenient day-night cycle can be experienced by the inhabitants. Since the edges of the Orbital are built as high walls, the rotation prevents the atmosphere from escaping, thus protecting the inhabitants from radiation. The walls are typically hundreds or thousands of kilometres high, made of a 'monocrystal' material.[6]

Governance

Responsibility for day-to-day administration of one of the Culture's Orbitals and the management of its complex systems mainly rests with a Mind,[7] which is situated in a structure in space at the centre of the Orbital, known as the Hub. The Mind is generally referred to simply as "Hub" by the inhabitants of the Orbitals, who never tend to be more than a millisecond away from the personalized contact and care it provides (via a contact terminal, usually worn as a piece of jewelry, or via a neural implant called a "neural lace").

As the Hub Mind is extremely advanced, it could simultaneously hold conversations with every one of the billions of citizens a fully settled Orbital has, and constantly controls millions of avatars, (usually) humanoid representatives of itself, throughout the world, though it can also interact in myriad other ways.[3] It will also provide near-instant aid or material comforts, usually via service drones or matter displacement - being a near-omnipresent, omniscient as well as generally all-benevolent presence in the life of an Orbital citizen. As an insurance policy against unscrupulous Hub Minds, and to represent the community to visitors from more traditionally hierarchical societies, each Orbital also elects a body called a General Board from among its human and drone population. As a further check on the power of the Hub Mind, matters of public concern are decided by referendum.

Other civilizations also build Orbitals (sometimes with the Culture's mentoring, as with The Affront), although it is not known if all of them are similarly managed.

Culture

The culture within the Orbitals is typical for the philosophic-hedonistic slant of all the Culture. They are also prime examples of the Culture's post-scarcity society, for within some physical limits, all material wishes can be fulfilled (or will be fulfilled by the Hub on request).

Orbital culture is thus heavy on enjoyment, arts and crafting, creative endeavours of all kinds, learning, as well as sports and games. The mere building of an Orbital is an adventure itself, in which the Hub Mind involves its inhabitants; beginning with two plates orbiting its future Hub, with more plates added to them at regular intervals. The final joining plates may not be fully formed and 'landscaped' until after a very long time - at least as measured from the viewpoint of a biological member of the Culture.

While the number of people living on an Orbital tends to be in the many billions,[1][2] the sheer size of the habitat, as well as the casual lifestyle of the Culture, ensure that it almost never feels crowded. Citizens can choose to withdraw into large areas of primal (if ultimately manufactured) nature or into their own spacious homesteads, and tend not to live in cities unless they prefer the increased activity and the proximity of friends.

Orbitals also serve as residences for 'Ambassadors' of other societies to the Culture - though as shown in some of the books, the Culture understands this term differently: the alien is fully intended to eventually consider the Culture superior to his own society and become an ambassador for the Culture.

To some extent, living on an Orbital is regarded in the Culture as a staid, provincial sort of existence, as compared to the cosmopolitan lifestyle aboard a spacefaring Ship.[8]

Appearance in novels

- Two books describe attempts to destroy Orbitals:

- Vavatch Orbital (an Orbital within space being strategically abandoned by the Culture due to the Idiran war[9], Vavatch Orbital itself is not a Culture-constructed or -administered Orbital) is the setting for a large part of the 1987 novel Consider Phlebas. Vavatch's circumference of fourteen million kilometres and width of thirty-five thousand kilometres - significantly larger than most Orbitals built by the Culture - also produce greater simulated gravity. Vavatch also does not provide the Culture's typical omnipresent hub mind assistance.

- Masaq' Orbital is the main setting for the 2000 novel Look to Windward. The hub mind of Masaq' was previously the ship Lasting Damage, and is both tormented by its actions during the Idiran-Culture War as well as the main target of another faction seeking revenge on the Culture.

- In the 1988 novel The Player of Games, Jernau Gurgeh sets off from Chiark Orbital on his Special Circumstances mission to play Azad.

- Yime Nsokyi sets off from Dinyol-hei Orbital in Surface Detail on her mission for the Quietudinal Service.

- Scoaliera Tefwe visits the drone Hassipura Plyn-Frie on Dibaldipen Orbital in The Hydrogen Sonata as part of her attempt to locate Ngaroe QiRia. The drone has built an elaborate 'sand garden' in a high mountain there.

Cultural influence

In the multimedia franchise Halo, characters have visited structures from which the series takes its name, and which are similar to an Orbital.[10] Halo's original developer Bungie has mentioned Banks' Culture as an inspiration for Halo.[11]

See also

- Dyson sphere

- Megastructure

- Ringworld

- Stanford torus

- Halo (megastructure)

- Bishop Ring (habitat)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Booker, M. Keith; Thomas, Anne-Marie (2009-05-05). The Science Fiction Handbook. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 1405162058. "[...] though most humans live primarily on huge Orbitals, artificial ring-like structures (with populations of many billions) that rotate in space near stars, something like the Ringworld envisioned by Larry Niven in his 1970 novel of the same title, except that an Orbital is much smaller and does not extend around its star, as does Niven's Ringworld."

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Jacobs, Alan. "The Ambiguous Utopia of Iain M. Banks". The New Atlantis. http://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/the-ambiguous-utopia-of-iain-m-banks. "A few of these worlds are planets, but far more often Culture citizens live on Orbitals—vast rings, each "like a god’s bracelet," that orbit stars and rotate in order to produce appropriate gravity -- and on great interstellar ships. (Tens of millions of people may live on a ship; tens of billions on an Orbital.)"

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Look to Windward. Orbit. 2000.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "A Few Notes on The Culture". http://nuwen.net/culture.html.

- ↑ Newitz, Annalee (2011-02-11). "Welcome to the Culture, the Galactic Civilization That Iain M. Banks Built". io9.com. http://io9.com/354739/welcome-to-the-culture-the-galactic-civilization-that-iain-m-banks-built. "The attraction of Orbitals is their matter efficiency. For one planet the size of Earth (population 6 billion at the moment; mass 6x1024 kg), it would be possible, using the same amount of matter, to build 1,500 full orbitals, each one boasting a surface area twenty times that of Earth and eventually holding a maximum population of perhaps 50 billion people (the Culture would regard Earth at present as over-crowded by a factor of about two, though it would consider the land-to-water ratio about right). Not, of course, that the Culture would do anything as delinquent as actually deconstructing a planet to make Orbitals; simply removing the sort of wandering debris (for example comets and asteroids) which the average solar system comes equipped with and which would threaten such an artificial world's integrity through collision almost always in itself provides sufficient material for the construction of at least one full Orbital (a trade-off whose conservatory elegance is almost blissfully appealing to the average Mind), while interstellar matter in the form of dust clouds, brown dwarfs and the like provides more distant mining sites from which the amount of mass required for several complete Orbitals may be removed with negligible effect."

- ↑ The Player of Games. 1988.

- ↑ Broderick, Damien (2012). "Terrible Angels: The Singularity and Science Fiction". Journal of Consciousness Studies 19 (1-2). "[...] postscarcity anarcho-communist polity is mostly located on starships and Orbitals run by AI Minds [...]".

- ↑ McCracken-Flesher, Caroline (2011-10-27). Scotland as Science Fiction. Bucknell University Press. ISBN 161148426X. "[...] yet he remains tethered to his home in the Culture. He carries with him a bracelet that is a replica of the orbital space structure on which he lives. Most members of the Culture live on traveling starships and look down on those living on orbitals as provincial. The bracelet thus calls attention to Gurgeh's rootedness [...]"

- ↑ Palmer, Christopher (March 1999). "Galactic Empires and the Contemporary Extravaganza: Dan Simmons and Iain M. Banks". Science Fiction Studies 26 (1). "The Clear Air Turbulence was docked within the Ends of Invention while the Culture organized the evacuation of an entire artificial planet, Vavatch Orbital, before destroying it.".

- ↑ Cuddy, Luke (2011-06-07). Halo and Philosophy: Intellect Evolved. Open Court. ISBN 0812697189. "[...] Banks put out the Culture series of books, which envisions a slightly smaller structure called an "orbital" -- probably closer to the Halo structures [...]"

- ↑ Sones, Benjamin E. (2000-07-14). "Bungie dreams of rings and things, part 2". Computer Games Online. Archived from the original on 2005-04-08. https://web.archive.org/web/20050408113351/http://www.cdmag.com/articles/028/170/halo_preview2.html. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

External links