Medicine:Glandular odontogenic cyst

| Glandular odontogenic cyst | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Sialo-Odontogenic cyst |

| |

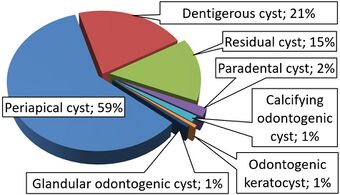

| Relative incidence of odontogenic cysts.[1] Glandular odontogenic cyst is labeled at bottom. | |

| Symptoms | Jaw expansion, swelling, impairment to the tooth, root and cortical plate [2][3] |

| Causes | Cellular mutation, cyst maturation at glandular, BCL-2 protein [2][4] |

| Diagnostic method | Biopsy, CT scans, Panoramic x-rays [5][6] |

| Differential diagnosis | Central mucoepidermoid carcinoma, odontogenic keratocyst [7][6] |

| Prevention | Post-surgery follow-ups are commonly proposed to prevent the chances of recurrence [6] |

| Treatment | Enucleation, curettage, marginal or partial resection, marsupialization[6] |

| Frequency | 0.12 to 0.13% of people [2] |

A glandular odontogenic cyst (GOC) is a rare and usually benign odontogenic cyst developed at the odontogenic epithelium of the mandible or maxilla.[2][8][9][10] Originally, the cyst was labeled as "sialo-odontogenic cyst" in 1987.[7] However, the World Health Organization (WHO) decided to adopt the medical expression "glandular odontogenic cyst".[9] Following the initial classification, only 60 medically documented cases were present in the population by 2003.[6] GOC was established as its own biological growth after differentiation from other jaw cysts such as the "central mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC)", a popular type of neoplasm at the salivary glands.[7][11] GOC is usually misdiagnosed with other lesions developed at the glandular and salivary gland due to the shared clinical signs.[12] The presence of osteodentin supports the concept of an odontogenic pathway.[10] This odontogenic cyst is commonly described to be a slow and aggressive development.[13] The inclination of GOC to be large and multilocular is associated with a greater chance of remission.[10][3] GOC is an infrequent manifestation with a 0.2% diagnosis in jaw lesion cases.[14] Reported cases show that GOC mainly impacts the mandible and male individuals.[3] The presentation of GOC at the maxilla has a very low rate of incidence.[8] The GOC development is more common in adults in their fifth and sixth decades.[1]

GOC has signs and symptoms of varying sensitivities, and dysfunction.[13][14] In some cases, the GOC will present no classic abnormalities and remains undiagnosed until secondary complications arise.[13] The proliferation of GOC requires insight into the foundations of its unique histochemistry and biology.[7] The comparable characteristics of GOC with other jaw lesions require the close examination of its histology, morphology, and immunocytochemistry for a differential diagnosis.[10] Treatment modes of the GOC follow a case-by-case approach due to the variable nature of the cyst.[5] The selected treatment must be accompanied with an appropriate pre and post-operative plan.[5]

Signs and Symptoms

The appearance of a protrusive growth will be present at their mandible or maxilla.[2] The expansive nature of this cyst may destruct the quality of symmetry at the facial region and would be a clear physical sign of abnormality.[2][7] The area of impact may likely be at the anterior region of mandible as described in a significant number of reported cases.[8] At this region, GOC would eventually mediate expansion at the molars.[7] A painful and swollen sensation at the jaw region caused by GOC may be reported.[14] Detailing of a painless feeling or facial paraesthesia can be experienced.[7][14] Alongside GOC, "root resorption, cortical bone thinning and perforation, and tooth displacement may occur".[3] Experience of swelling at the buccal and lingual zones can occur.[6] Usually, the smaller sized GOCs present no classical signs or symptoms to the case (i.e. "asymptomatic").[4] GOC is filled with cystic a fluid that differs in viscosity and may appear as transparent, brownish-red, or creamy in colour.[3]

Causes

The GOC can arise through a number of causes:[7]

The origin of the GOC can be understood through its biological and histochemistry foundations.[4] It has been suggested that GOC can be a result of a traumatic event.[12] The occurrence of GOC may be from a mutated cell from "the oral mucosa and the dental follicle" origin.[15] Another probable cause is from pre-existing cysts or cancerous constituents.[12] A potential biological origin of GOC is a cyst developed at a salivary gland or simple epithelium, which undergoes maturation at the glandular.[4] Another origin is a primordial cyst that infiltrates the glandular epithelial tissue through a highly organised cellular differentiation.[4] Pathologists discovered a BCL-2 protein, commonly present in neoplasms, to exist in the tissue layers of the GOC.[4][15] The protein is capable of disrupting normal cell death function at the odontogenic region.[4][15] The analysis of PTCH, a gene that specialises in neoplasm inhibition, was carried out to determine if any existing mutations played a role in the initiation of the GOC.[7] It is confirmed that the gene had no assistance in triggering cystic advancement.[7]

Diagnosis

Radiology

The performance of radiographic imaging i.e. computed tomography, at the affected area is considered essential.[13] Radiographic imaging of the GOC can display a defined unilocular or multilocular appearance that may be "rounded or oval" shaped upon clinical observation.[5][4] Scans may present a distribution of the GOC at the upper jaw as it presents a 71.8% prevalence in cases.[2] The margin surrounding the GOC is usually occupied with a scalloped definition.[2] A bilateral presentation of the GOC is possible but is not common at either the maxilla or mandible sites.[13] The GOC has an average size of 4.9 cm that can develop over the midline when positioned at the mandible or maxilla region.[3][14] Analysis of scans allow for the differentiation of GOC from other parallel lesions, i.e. "ameloblastoma, odontogenic myxoma, or dentigerous cyst" in order to minimise the chance of a misdiagnosis.[5] These scans can display the severity of cortical plate, root, and tooth complications, which is observed to determine the necessary action for reconstruction.[5]

Histology

Histological features related to the GOC differ in each scenario; however, there is a general criterion to identify the cyst.[14] The GOC usually features a "stratified squamous epithelium" attached to connective tissue that is filled with active immune cells.[2][7] The lining of the epithelium features a very small diameter that is usually non-keratinised.[8][13] In contrast, the lining of the GOC has rather an inconsistent diameter.[2] The basal cells of the GOC usually has no association to a cancerous origin.[12] Tissue cells can be faced with an abnormal increase in the concentration of calcium, which can cause the region to calcify.[7] The transformation of the epithelium is associated with a focal luminal development.[2] Eosinophilic organelles such as columnar and cuboidal cells can be observed during microscopy.[11] Intra-epithelial crypts may be identified in the internal framework of the epithelium or at the external space where it presents itself as papillae protrusions.[8][13] Mucin is observable after the application of "alcian blue dye" on the tissue specimen.[8] The histological observation of goblet cells is a common feature with the "odontogenic dentigerous cyst".[11] In some circumstances, the epithelium can have variable plaque structures that appear as swirls in the tissue layers.[8] Interestingly, histologists were able to identify hyaline bodies within the tissue framework of the GOC.[7] It is encouraged that the histological identification of at least seven of these biological characteristics is required to accurately distinguish the presence of the GOC.[11]

Intraepithelial Hemosiderin

Pathologists have identified hemosiderin pigments that are considered unique to the GOC.[12] The discovery of this pigment can be pivotal to the differentiation of the GOC from other lesions.[12] The staining at the epithelium is due to the haemorrhaging of the lining.[12] The cause of the haemorrhaging can be triggered by the type of treatment, cellular degradation, or structural deformation inflicted during GOC expansion.[12] Examination of the GOC tissue section indicated that red blood cells from the intraluminal space had combined with the extracellular constituents.[12] This process is carried out through transepithelial elimination.[12] This clinical procedure is beneficial to confirm the benign or malignant nature of the GOC.[12]

Immunocytochemistry

The examination of cytokeratin profiles is deemed useful when observing the differences between the GOC and the central MEC.[14] These two lesions show individualised expression for cytokeratin 18 and 19.[7] Past studies observed Ki-67, p53, and PCNA expression in common jaw cysts that shared similar characteristics.[7] There was a lack of p53 expression found in radicular cysts.[7] Similarly, Ki-67 was seen less in the central MEC compared to the other lesions, though this discovery is not essential to the process of differential diagnosis.[7][14] Proliferating cell nuclear antigen readings were established to have no role in the differentiation process.[14] The TGF-beta marker is present in the GOC and can explain the limited concentration of normal functioning cells.[15]

MAML2 rearrangement

The observation of a MAML2 rearrangement is described as a procedure useful in the differential diagnosis of the GOC and its closely related lesion, the central MEC.[11] A second cystic development displayed the presence of CRTC3-MAML2 fusion after an in-vitro application.[11] The MAML2 rearrangement represents the developmental growth of the central MEC from the GOC.[11] The use of fusion-gene transcript may be helpful towards the differentiation of the GOC from the central MEC of the jaw and salivary glands.[11]

Treatment

Pre-treatment protocols

A computed tomography and panoramic x-ray must be undertaken in order to observe the severity of internal complications.[5] These scans allow for the observation of the GOC size, radiolucency, cortical bone, dentition, root, and vestibular zone.[5] In some cases, the dentition may be embedded into the cavity walls of the lesion, depending on the position of expansion at the odontogenic tissue.[13] The diagnosis of a smaller sized GOC is related to the attachment of only two teeth.[6] While, a greater sized GOC develops over two teeth.[6] Presentation of a greater sized lesion usually requires a biopsy for a differential diagnosis and a precise treatment plan.[6]

Treatment process

The unilocular and multilocular nature is imperative to the determination of treatment style.[6] Local anesthesia is regularly provided as the GOC is embedded within the tissue structure of the jaw and requires an invasive procedure for a safe and accurate extraction.[2] For unilocular GOCs with minimal tissue deterioration, "enucleation, curettage, and marsupialization" is a suitable treatment plan.[6] Notably, the performance of enucleation or curettage as the primary action is linked to an incomplete extraction of the GOC and is only recommended to the less invasive lesions.[6] Multilocular GOCs require a more invasive procedure such as "peripheral ostectomy, marginal resection, or partial jaw resection".[6] GOCs associated with a more severe structural damage are encouraged to undergo marsupialization as either an initial or supplementary surgery.[6] The frequency of reappearance is likely due to the lingering cystic tissue structures that remain after the performance of curettage.[13] The incorporation of a "dredging method i.e. repetition of enucleation and curettage" is also suggested until the remnants of the GOC diminishes for certain.[9] The treatment ensures scar tissue is removed to promote the successful reconstruction of osseous material for jaw preservation.[9] Alongside the main treatments, bone allograft application, cryosurgery, and apicoectomy are available but have not been consistently recommended.[9][13][5] Though Carnoy's solution, the chloroform-free version, is recommended with the treatment as it degenerates the majority of the damaged dental lamina.[13] The most effective type of treatment remains unknown due to the lack of detailed data from reported cases.[3]

Post-treatment protocols

Follow-up appointments are necessary after the removal of the GOC as there is a high chance of remission, which may be exacerbated in cases dealing with "cortical plate perforation".[13][5] The GOC has a significant remission rate of 21 to 55% that can potentially develop during the period of 0.5 to 7 years post-surgery.[7][6] Cases occupied with a lower risk lesion are expected to continue appointments with physicians for up to 3 years post-surgery.[6] A higher risk lesion is encouraged to consistently consult with physicians during a 7-year period after treatment.[13] Remission events require immediate attention and appropriate procedures such as enucleation or curettage.[6] In more damaging cases of remission, tissue resection, and marsupialization may have to be performed.[7]

Epidemiology

The clinical presentation of the GOC is very low in the population as noted by the 0.12 to 0.13% occurrence rate, extrapolated from a sample size of the 181 individuals.[2] The GOC mainly affects older individuals in the population, especially those that are in their 40 to 60s.[8] However, the GOC can affect younger individuals i.e. 11, and more older individuals i.e. 82 in the population.[2] The age distribution starts at a much lower number for people living in Asia and Africa.[2] Those in their first 10 years of life have not been diagnosed with the GOC.[14] The GOC does present a tendency to proliferate in more males than females.[3] There is no definitive conclusion towards the relevance of gender and its influence on the rate of incidence.[7]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Borges, Leandro Bezerra; Fechine, Francisco Vagnaldo; Mota, Mário Rogério Lima; Sousa, Fabrício Bitu; Alves, Ana Paula Negreiros Nunes (March 2012). "Odontogenic lesions of the jaw: a clinical-pathological study of 461 cases". Revista Gaúcha de Odontologia 60 (1): 71–78. http://www.revistargo.com.br/viewarticle.php?id=2229.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 Faisal, Mohammad; Ahmad, Syed Ansar; Ansari, Uzma (September 2015). "Glandular odontogenic cyst – Literature review and report of a paediatric case". Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research 5 (3): 219–225. doi:10.1016/j.jobcr.2015.06.011. PMID 26587384.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Momeni Roochi, Mehrnoush; Tavakoli, Iman; Ghazi, Fatemeh Mojgan; Tavakoli, Ali (1 July 2015). "Case series and review of glandular odontogenic cyst with emphasis on treatment modalities". Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 43 (6): 746–750. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2015.03.030. PMID 25971944.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Patel, Govind; Shah, Monali; Kale, Hemant; Ranginwala, Amena (2014). "Glandular odontogenic cyst: A rare entity". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology 18 (1): 89–92. doi:10.4103/0973-029X.131922. PMID 24959044.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 Cano, Jorge; Benito, Dulce María; Montáns, José; Rodríguez-Vázquez, José Francisco; Campo, Julián; Colmenero, César (1 July 2012). "Glandular odontogenic cyst: Two high-risk cases treated with conservative approaches". Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 40 (5): e131–e136. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2011.07.005. PMID 21865053.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 6.14 6.15 6.16 Kaplan, Ilana; Gal, Gavriel; Anavi, Yakir; Manor, Ronen; Calderon, Shlomo (April 2005). "Glandular odontogenic cyst: Treatment and recurrence". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 63 (4): 435–441. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2004.08.007. PMID 15789313.

- ↑ 7.00 7.01 7.02 7.03 7.04 7.05 7.06 7.07 7.08 7.09 7.10 7.11 7.12 7.13 7.14 7.15 7.16 7.17 7.18 7.19 Shear, Mervyn; Speight, Paul, eds (2007). "Glandular Odontogenic Cyst (Sialo-Odontogenic Cyst)". Cysts of the Oral and Maxillofacial Regions. pp. 94–99. doi:10.1002/9780470759769.ch7. ISBN 978-0-470-75976-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=Jgt7046OlUAC&pg=PA94.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Prabhu, Sudeendra; Rekha, K; Kumar, GS (2010). "Glandular odontogenic cyst mimicking central mucoepidermoid carcinoma". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology 14 (1): 12–5. doi:10.4103/0973-029X.64303. PMID 21180452.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Motooka, Naomi; Ohba, Seigo; Uehara, Masataka; Fujita, Syuichi; Asahina, Izumi (1 January 2015). "A case of glandular odontogenic cyst in the mandible treated with the dredging method". Odontology 103 (1): 112–115. doi:10.1007/s10266-013-0143-0. PMID 24374982.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Shah, AmishaA; Sangle, Amit; Bussari, Smita; Koshy, AjitV (2016). "Glandular odontogenic cyst: A diagnostic dilemma". Indian Journal of Dentistry 7 (1): 38–43. doi:10.4103/0975-962X.179371. PMID 27134453.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Nagasaki, Atsuhiro; Ogawa, Ikuko; Sato, Yukiko; Takeuchi, Kengo; Kitagawa, Masae; Ando, Toshinori; Sakamoto, Shinnichi; Shrestha, Madhu et al. (January 2018). "Central mucoepidermoid carcinoma arising from glandular odontogenic cyst confirmed by analysis of MAML2 rearrangement: A case report: Central MEC arising from GOC". Pathology International 68 (1): 31–35. doi:10.1111/pin.12609. PMID 29131467.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 AbdullGaffar, Badr; Koilelat, Mohamed (May 2017). "Glandular Odontogenic Cyst: The Value of Intraepithelial Hemosiderin". International Journal of Surgical Pathology 25 (3): 250–252. doi:10.1177/1066896916672333. PMID 27829208.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 Akkaş, İsmail; Toptaş, Orçun; Özan, Fatih; Yılmaz, Fahri (1 March 2015). "Bilateral Glandular Odontogenic Cyst of Mandible: A Rare Occurrence". Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery 14 (1): 443–447. doi:10.1007/s12663-014-0668-y. PMID 25848155.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.7 14.8 14.9 Neville, Brad W. (2016). "Cyst, Glandular Odontogenic". in Slootweg, Pieter. Dental and Oral Pathology. Encyclopedia of Pathology. Springer International Publishing. pp. 89–93. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28085-1_677. ISBN 978-3-319-28084-4.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Alaeddini, Mojgan; Eshghyar, Nosratollah; Etemad‐Moghadam, Shahroo (2017). "Expression of podoplanin and TGF-beta in glandular odontogenic cyst and its comparison with developmental and inflammatory odontogenic cystic lesions". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine 46 (1): 76–80. doi:10.1111/jop.12475. PMID 27391558.

Bibliography

- AbdullGaffar, Badr; Koilelat, Mohamed (May 2017). "Glandular Odontogenic Cyst: The Value of Intraepithelial Hemosiderin". International Journal of Surgical Pathology 25 (3): 250–252. doi:10.1177/1066896916672333. PMID 27829208.

- Akkaş, İsmail; Toptaş, Orçun; Özan, Fatih; Yılmaz, Fahri (1 March 2015). "Bilateral Glandular Odontogenic Cyst of Mandible: A Rare Occurrence". Journal of Maxillofacial and Oral Surgery 14 (1): 443–447. doi:10.1007/s12663-014-0668-y. PMID 25848155.

- Alaeddini, Mojgan; Eshghyar, Nosratollah; Etemad‐Moghadam, Shahroo (2017). "Expression of podoplanin and TGF-beta in glandular odontogenic cyst and its comparison with developmental and inflammatory odontogenic cystic lesions". Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine 46 (1): 76–80. doi:10.1111/jop.12475. PMID 27391558.

- Borges, Leandro Bezerra; Fechine, Francisco Vagnaldo; Mota, Mário Rogério Lima; Sousa, Fabrício Bitu; Alves, Ana Paula Negreiros Nunes (March 2012). "Odontogenic lesions of the jaw: a clinical-pathological study of 461 cases". Revista Gaúcha de Odontologia 60 (1): 71–78. http://www.revistargo.com.br/viewarticle.php?id=2229.

- Cano, Jorge; Benito, Dulce María; Montáns, José; Rodríguez-Vázquez, José Francisco; Campo, Julián; Colmenero, César (1 July 2012). "Glandular odontogenic cyst: Two high-risk cases treated with conservative approaches". Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 40 (5): e131–e136. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2011.07.005. PMID 21865053.

- Faisal, Mohammad; Ahmad, Syed Ansar; Ansari, Uzma (September 2015). "Glandular odontogenic cyst – Literature review and report of a paediatric case". Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research 5 (3): 219–225. doi:10.1016/j.jobcr.2015.06.011. PMID 26587384.

- Kaplan, Ilana; Gal, Gavriel; Anavi, Yakir; Manor, Ronen; Calderon, Shlomo (April 2005). "Glandular odontogenic cyst: Treatment and recurrence". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 63 (4): 435–441. doi:10.1016/j.joms.2004.08.007. PMID 15789313.

- Motooka, Naomi; Ohba, Seigo; Uehara, Masataka; Fujita, Syuichi; Asahina, Izumi (1 January 2015). "A case of glandular odontogenic cyst in the mandible treated with the dredging method". Odontology 103 (1): 112–115. doi:10.1007/s10266-013-0143-0. PMID 24374982.

- Nagasaki, Atsuhiro; Ogawa, Ikuko; Sato, Yukiko; Takeuchi, Kengo; Kitagawa, Masae; Ando, Toshinori; Sakamoto, Shinnichi; Shrestha, Madhu et al. (January 2018). "Central mucoepidermoid carcinoma arising from glandular odontogenic cyst confirmed by analysis of MAML2 rearrangement: A case report: Central MEC arising from GOC". Pathology International 68 (1): 31–35. doi:10.1111/pin.12609. PMID 29131467.

- Neville, Brad W. (2016). "Cyst, Glandular Odontogenic". in Slootweg, Pieter. Dental and Oral Pathology. Encyclopedia of Pathology. Springer International Publishing. pp. 89–93. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-28085-1_677. ISBN 978-3-319-28084-4.

- Prabhu, Sudeendra; Rekha, K; Kumar, GS (2010). "Glandular odontogenic cyst mimicking central mucoepidermoid carcinoma". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology 14 (1): 12–5. doi:10.4103/0973-029X.64303. PMID 21180452.

- Momeni Roochi, Mehrnoush; Tavakoli, Iman; Ghazi, Fatemeh Mojgan; Tavakoli, Ali (1 July 2015). "Case series and review of glandular odontogenic cyst with emphasis on treatment modalities". Journal of Cranio-Maxillofacial Surgery 43 (6): 746–750. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2015.03.030. PMID 25971944.

- Patel, Govind; Shah, Monali; Kale, Hemant; Ranginwala, Amena (2014). "Glandular odontogenic cyst: A rare entity". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology 18 (1): 89–92. doi:10.4103/0973-029X.131922. PMID 24959044.

- Shah, AmishaA; Sangle, Amit; Bussari, Smita; Koshy, AjitV (2016). "Glandular odontogenic cyst: A diagnostic dilemma". Indian Journal of Dentistry 7 (1): 38–43. doi:10.4103/0975-962X.179371. PMID 27134453.

- Shear, Mervyn; Speight, Paul, eds (2007). "Glandular Odontogenic Cyst (Sialo-Odontogenic Cyst)". Cysts of the Oral and Maxillofacial Regions. pp. 94–99. doi:10.1002/9780470759769.ch7. ISBN 978-0-470-75976-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=Jgt7046OlUAC&pg=PA94.

Further reading

- Kahn, Michael A. (2001). Basic Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 1.