Medicine:Epidemiology of childhood obesity

Prevalence of childhood obesity has increased worldwide. The world health organization (WHO) estimated that 39 million children younger than 5 years of age were overweight or had obesity in 2020, and that 340 million children between 5 and 19 were overweight or had obesity in 2016.[1] If the trend continues at the same rate as seen after the year 2000, it could have been expected that there would be more children with obesity than moderate or severe undernutrition in 2022.[2] However, the Covid-19 pandemic will most likely effect the prevalence of undernutrition and obesity[3]

In 2010 that the prevalence of childhood obesity during the past two to three decades, much like the United States , has increased in most other industrialized nations, excluding Russia and Poland .[4] Between the early 1970s and late 1990s, prevalence of childhood obesity doubled or tripled in Australia , Brazil , Canada , Chile , Finland , France , Germany , Greece, Japan , the United Kingdom , and the USA.[4]

A 2010 article from the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition analyzed global prevalence from 144 countries in preschool children (less than 5 years old).[5] Cross-sectional surveys from 144 countries were used and overweight and obesity were defined as preschool children with values >3SDs from the mean.[5] They found an estimated 42 million obese children under the age of five in the world of which close to 35 million lived in developing countries.11 Additional findings included worldwide prevalence of childhood overweight and obesity increasing from 4.2% (95% CI: 3.2%, 5.2%) in 1990 to 6.7% (95% CI: 5.6%, 7.7%) in 2010 and expecting to rise to 9.1% (95% CI: 7.3%, 10.9%), an estimated 60 million overweight and obese children in 2020.[5]

Family and the public view

Children are often viewed as the vulnerable population, needing more attention from government policies and family. The media also portrays this in shows and movies, which can bring a negative effect towards parents whose children are obese by placing blame and responsibility solely in the parents.[6]

United States

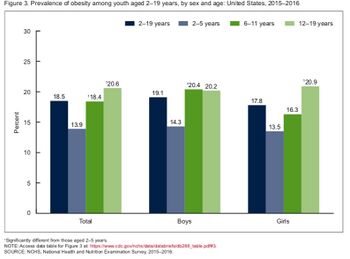

Childhood obesity in the United States, has been a serious problem among children and adolescents, and can cause serious health problems among our youth. According to the CDC, as of 2015–2016, in the United States, 18.5% of children and adolescents have obesity, which affects approximately 13.7 million children and adolescents. It affects children of all ages and some ethnic groups more than others, 25.8% Hispanics, 22.0% non-Hispanic blacks, 14.1% non-Hispanic white children are affected by obesity.[7] Prevalence has remained high over the past three decades across most age, sex, racial/ethnic, and socioeconomic groups, and represents a three-fold increase from one generation ago and is expected to continue rising.[8][9]

Prevalence of pediatric obesity also varies with state. The highest rates of childhood obesity are found in the southeastern states of which Mississippi was found to have the highest rate of overweight/obese children, 44.5%/21.9% respectively.[10] The western states were found to have the lowest prevalence, such as Utah (23.1%) and Oregon (9.6%).[11]

From 2003 to 2007, there was a twofold increase in states reporting prevalence of pediatric obesity greater than or equal to 18%.7 Oregon was the only state showing decline from 2003 to 2007 (decline by 32%), and using children in Oregon as a reference group, obesity in children in Illinois, Tennessee , Kentucky, West Virginia, Georgia, and Kansas has doubled.[11]

The likelihood of obesity in children was found to increase significantly with decreasing levels of household income, lower neighborhood access to parks or sidewalks, increased television viewing time, and increased recreational computer time.[12] Black and Hispanic children are more likely to be obese compared to white (Blacks OR=1.71 and Hispanics=1.76).[12]

Prevalence

According to the CDC, For the 2015–2016 year, the CDC found that the prevalence of obesity for children aged 2–19 years old, in the U.S., was 18.5%.[7] The current trends show that children aged 12–19 years old, have obesity levels 2.2% higher than children 6–11 years old (20.6% vs. 18.4%), and children 6–11 years old have obesity levels 4.5% higher than children aged 2–5 years old (18.4% vs. 13.9%). Boys, 6–19 years old, have a 6.1% higher prevalence of obesity, than boys aged 2–5 years old (20.4% vs. 14.3%). While girls aged 12–19 years old, have a 7.4% greater prevalence of obesity, than girls aged 2–5 years old (20.9% vs. 13.5%).[7]

A 2010 NCHS Data Brief published by the CDC found interesting trends in prevalence of childhood obesity.[13] The prevalence of obesity among boys from households with an income at or above 350% the poverty level was found to be 11.9%, while boys with a household income level at or above 130% of the poverty level was 21.1%.[13] The same trend followed in girls. Girls with a household income at or above 350% of the poverty level has an obesity prevalence of 12.0%, while girls with a household income 130% below the poverty level had a 19.3% prevalence.[13]

These trends were not consistent when stratified according to race. “The relationship between income and obesity prevalence is significant among non-Hispanic white boys; 10.2% of those living in households with income at or above 350% of the poverty level are obese compared with 20.7% of those in households below 130% of the poverty level.”[13] The same trend follows in non-Hispanic white girls (10.6% of those living at or above 350% of the poverty level are obese, and 18.3% of those living below 130% of the poverty level are obese)[13]

There is no significant trend in prevalence by income level for either boys or girls among non-Hispanic black and Mexican-American children and adolescents.[13] “In fact, the relationship does not appear to be consistent; among Mexican-American girls, although the difference is not significant, 21.0% of those living at or above 350% of the poverty level are obese compared with 16.2% of those living below 130% of the poverty level.” [13]

Additional findings also include that the majority of children and adolescents are not low income children.[13] The majority of non-Hispanic white children and adolescents also live in households with income levels at or above 130% of the poverty level.[13] Approximately 7.5 million children live in households with income levels above 130% of the poverty level compared to 4.5 million children in households with income at or above 130% of the poverty level.[13]

Incidence

The importance of identifying the incidence of age-related onset of obesity is vital to understanding when intervention opportunities are most important. Similarly, identifying the incidence of childhood obesity within a respective race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, can also help delineate other areas of intervention opportunities for certain populations. A systematic review on the incidence of childhood obesity, found that childhood obesity in the U.S. declines with age.[14] The age-and-sex related incidence of obesity was found to be "4.0% for infants 0–1.9 years, 4.0% for preschool-aged children 2.0–4.9 years, 3.2% for school-aged children 5.0–12.9 years, and 1.8% for adolescents 13.0–18.0 years." When the incidence of childhood obesity, was isolated for the socioeconomically disadvantaged, or for racial/ethnic minority groups, obesity incidence was discovered to be, "4.0% at ages 0–1.9 years, 4.1% at 2.0–4.9 years, 4.4% at 5.0–12.9 years, and 2.2% at 13.0–18.0 years."[14]

Based on a 2015-2016 National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES), researchers at Duke University, found that the incidence of childhood obesity is on the rise, with a notable rise in preschool boys (2.0-4.9 years), and girls aged 16.0-19.0 years old. The Duke University researchers also discovered that although it had been believed that obesity in children had been on a decline in recent years, obesity in children at all ages has actually been increasing.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ "Obesity and overweight" (in en). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- ↑ NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) (October 10, 2017). "Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents and adults". The Lancet 390 (10113): 2627–2642. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 29029897.

- ↑ Zemrani, Boutaina; Gehri, Mario; Masserey, Eric; Knob, Cyril; Pellaton, Rachel (22 January 2021). "A hidden side of the COVID-19 pandemic in children: the double burden of undernutrition and overnutrition" (in en). International Journal for Equity in Health 20 (1): 44. doi:10.1186/s12939-021-01390-w. ISSN 1475-9276. PMID 33482829.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Childhood obesity". Lancet 375 (9727): 1737–48. May 2010. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)60171-7. PMID 20451244.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Global prevalence and trends of overweight and obesity among preschool children". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 92 (5): 1257–64. November 2010. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2010.29786. PMID 20861173.

- ↑ "The role of parents in public views of strategies to address childhood obesity in the United States". The Milbank Quarterly 93 (1): 73–111. March 2015. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.12106. PMID 25752351.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Childhood Obesity Facts | Overweight & Obesity | CDC" (in en-us). United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018-08-14. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/childhood.html.

- ↑ "Pediatric obesity epidemiology". Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes and Obesity 18 (1): 14–22. February 2011. doi:10.1097/med.0b013e3283423de1. PMID 21157323.

- ↑ "Changes in state-specific childhood obesity and overweight prevalence in the United States from 2003 to 2007". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 164 (7): 598–607. July 2010. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.84. PMID 20603458.

- ↑ "Construction of the World Health Organization child growth standards: selection of methods for attained growth curves". Statistics in Medicine 25 (2): 247–65. January 2006. doi:10.1002/sim.2227. PMID 16143968.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Changes in state-specific childhood obesity and overweight prevalence in the United States from 2003 to 2007". Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 164 (7): 598–607. July 2010. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.84. PMID 20603458. http://archpedi.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/164/7/598.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Obesity and overweight for professionals: Childhood: Basics". United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/basics.html.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 13.8 13.9 "Obesity and socioeconomic status in children and adolescents: United States, 2005-2008". NCHS Data Brief (51): 1–8. December 2010. PMID 21211166.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Childhood Obesity Incidence in the United States: A Systematic Review". Childhood Obesity 12 (1): 1–11. February 2016. doi:10.1089/chi.2015.0055. PMID 26618249.

- ↑ "Incidence of childhood obesity continues to rise". https://www.foodbusinessnews.net/articles/11368-incidence-of-childhood-obesity-continues-to-rise.

|