Physics:ITU-R 468 noise weighting

ITU-R 468 (originally defined in CCIR recommendation 468-4, therefore formerly also known as CCIR weighting; sometimes referred to as CCIR-1k) is a standard relating to noise measurement, widely used when measuring noise in audio systems. The standard,[1] now referred to as ITU-R BS.468-4, defines a weighting filter curve, together with a quasi-peak rectifier having special characteristics as defined by specified tone-burst tests. It is currently maintained by the International Telecommunication Union who took it over from the CCIR.

It is used especially in the UK, Europe, and former countries of the British Empire such as Australia and South Africa.[citation needed] It is less well known in the USA where A-weighting has always been used.[2]

M-weighting is a closely related filter, an offset version of the same curve, without the quasi-peak detector.

Explanation

The A-weighting curve was based on the 40 phon equal-loudness contour derived initially by Fletcher and Munson (1933). Originally incorporated into an ANSI standard for sound level meters, A-weighting was intended for measurement of the audibility of sounds by themselves. It was never specifically intended for the measurement of the more random (near-white or pink) noise in electronic equipment, though has been used for this purpose by most microphone manufacturers since the 1970s. The human ear responds quite differently to clicks and bursts of random noise, and it is this difference that gave rise to the CCIR-468 weighting curve (now supported as an ITU standard), which together with quasi-peak measurement (rather than the rms measurement used with A-weighting) became widely used by broadcasters throughout Britain, Europe, and former British Commonwealth countries, where engineers were heavily influenced by BBC test methods. Telephone companies worldwide have also used methods similar to ITU-R 468 weighting with quasi-peak measurement to describe objectionable interference induced in one telephone circuit by switching transients in another.

History

Original research

Developments in the 1960s, in particular the spread of FM broadcasting and the development of the compact audio cassette with Dolby-B Noise Reduction, alerted engineers to the need for a weighting curve that gave subjectively meaningful results on the typical random noise that limited the performance of broadcast circuits, equipment and radio circuits. A-weighting was not giving consistent results, especially on FM radio transmissions and Compact Cassette recording where preemphasis of high frequencies was resulting in increased noise readings that did not correlate with subjective effect. Early efforts to produce a better weighting curve led to a DIN standard that was adopted for European Hi-Fi equipment measurement for a while.

Experiments in the BBC led to BBC Research Department Report EL-17, The Assessment of Noise in Audio Frequency Circuits,[3] in which experiments on numerous test subjects were reported, using a variety of noises ranging from clicks to tone-bursts to pink noise. Subjects were asked to compare these with a 1 kHz tone, and final scores were then compared with measured noise levels using various combinations of weighting filter and quasi-peak detector then in existence (such as those defined in a now discontinued German DIN standard). This led to the CCIR-468 standard which defined a new weighting curve and quasi-peak rectifier.

The origin of the current ITU-R 468 weighting curve can be traced to 1956. The 1968 BBC EL-17 report discusses several weighting curves, including one identified as D.P.B. which was chosen as superior to the alternatives: A.S.A, C.C.I.F and O.I.R.T. The report's graph of the DPB curve is identical to that of the ITU-R 468 curve, except that the latter extends to slightly lower and higher frequencies. The BBC report states that this curve was given in a "contribution by the D.B.P. (The Telephone Administration of the Federal German Republic) in the Red Book Vol. 1 1957 covering the first plenary assembly of the CCITT (Geneva 1956)". D.B.P. is Deutsche Bundespost, the German post office which provides telephone service in Germany as the GPO does in the UK. The BBC report states "this characteristic is based on subjective tests described by Belger." and cites a 1953 paper by E. Belger.

Dolby Laboratories took up the new CCIR-468 weighting for use in measuring noise on their noise reduction systems, both in cinema (Dolby A) and on cassette decks (Dolby B), where other methods of measurement were failing to show up the advantage of such noise reduction. Some Hi-Fi column writers took up 468 weighting enthusiastically, observing that it reflected the roughly 10 dB improvement in noise observed subjectively on cassette recordings when using Dolby B while other methods could indicate an actual worsening in some circumstances, because they did not sufficiently attenuate noise above 10 kHz.

Standards

CCIR Recommendation 468-1 was published soon after this report, and appears to have been based on the BBC work. Later versions up to CCIR 468-4 differed only in minor changes to permitted tolerances. This standard was then incorporated into many other national and international standards (IEC, BSI, JIS, ITU) and adopted widely as the standard method for measuring noise, in broadcasting, professional audio, and 'Hi-Fi' specifications throughout the 1970s. When the CCIR ceased to exist, the standard was officially taken over by the ITU-R (International Telecommunication Union). Current work on this standard occurs primarily in the maintenance of IEC 60268, the international standard for sound systems.

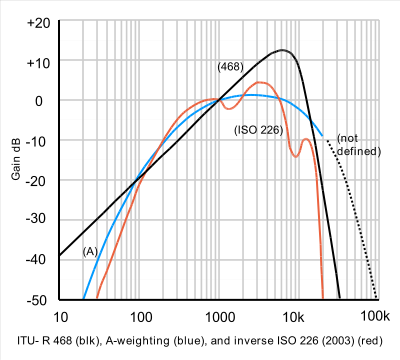

The CCIR curve differs greatly from A-weighting in the 5 to 8 kHz region where it peaks to +12.2 dB at 6.3 kHz, the region in which we appear to be extremely sensitive to noise. While it has been said (incorrectly) that the difference is due to a requirement for assessing noise intrusiveness in the presence of programme material, rather than just loudness, the BBC report makes clear the fact that this was not the basis of the experiments. The real reason for the difference probably relates to the way in which our ears analyse sounds in terms of spectral content along the cochlea. This behaves like a set of closely spaced filters with a roughly constant Q factor, that is, bandwidths proportional to their centre frequencies. High frequency hair cells would therefore be sensitive to a greater proportion of the total energy in noise than low frequency hair cells. Though hair-cell responses are not exactly constant Q, and matters are further complicated by the way in which the brain integrates adjacent hair-cell outputs, the resultant effect appears roughly as a tilt centred on 1 kHz imposed on the A-weighting.

Dependent on spectral content, 468-weighted measurements of noise are generally about 11 dB higher than A-weighted, and this is probably a factor in the recent trend away from 468-weighting in equipment specifications as cassette tape use declines.

It is important to realise that the 468 specification covers both weighted and 'unweighted' (using a 22 Hz to 22 kHz 18 dB/octave bandpass filter) measurement and that both use a very special quasi-peak rectifier with carefully devised dynamics (A-weighting uses RMS detection for no particular reason[citation needed]). Rather than having a simple 'integration time' this detector requires implementation with two cascaded 'peak followers' each with different attack time-constants carefully chosen to control the response to both single and repeating tone-bursts of various durations. This ensures that measurements on impulsive noise take proper account of our reduced hearing sensitivity to short bursts. This quasi-peak measurement is also called psophometric weighting.

This was once more important because outside broadcasts were carried over 'music circuits' that used telephone lines, with clicks from Strowger and other electromechanical telephone exchanges. It now finds fresh relevance in the measurement of noise on computer 'Audio Cards' which commonly suffer clicks as drives start and stop.

Present usage of 468-weighting

468-weighting is also used in weighted distortion measurement at 1 kHz. Weighting the distortion residue after removal of the fundamental emphasises high-order harmonics, but only up to 10 kHz or so where the ears response falls off. This results in a single measurement (sometimes called distortion residue measurement) which has been claimed to correspond well with subjective effect even for power amplifiers where crossover distortion is known to be far more audible than normal THD (total harmonic distortion) measurements would suggest.

468-weighting is still demanded by the BBC and many other broadcasters,[4] with increasing awareness of its existence and the fact that it is more valid on random noise where pure tones do not exist.[citation needed]

Often both A-weighted and 468-weighted figures are quoted for noise, especially in microphone specifications.

While not intended for this application, the 468 curve has also been used (offset to place the 0 dB point at 2 kHz rather than 1 kHz) as "M weighting" in standards such as ISO 21727[5] intended to gauge loudness or annoyance of cinema soundtracks. This application of the weighting curve does not include the quasi-peak detector specified in the ITU standard.

Summary of specification

Note: this is not the full definitive standard.

Weighting curve specification (weighted measurement)

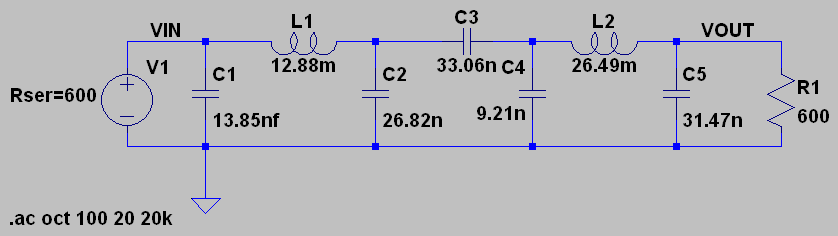

The weighting curve is specified by both a circuit diagram of a weighting network and a table of amplitude responses.

Above is the ITU-R 468 Weighting Filter Circuit Diagram. The source and sink impedances are both 600 ohms (resistive), as shown in the diagram. The values are taken directly from the ITU-R 468 specification. Note that since this circuit is purely passive, it cannot create the additional 12 dB gain required; any results must be corrected by a factor of 8.1333, or +18.2 dB.

Table of amplitude responses:

| Frequency (Hz) | Response (dB) |

|---|---|

| 31.5 | -29.9 |

| 63 | -23.9 |

| 100 | -19.8 |

| 200 | -13.8 |

| 400 | -7.8 |

| 800 | -1.9 |

| 1,000 | 0.0 |

| 2,000 | +5.6 |

| 3,150 | +9.0 |

| 4,000 | +10.5 |

| 5,000 | +11.7 |

| 6,300 | +12.2 |

| 7,100 | +12.0 |

| 8,000 | +11.4 |

| 9,000 | +10.1 |

| 10,000 | +8.1 |

| 12,500 | 0.0 |

| 14,000 | -5.3 |

| 16,000 | -11.7 |

| 20,000 | -22.2 |

| 31,500 | -42.7 |

The values of the amplitude response table slightly differ from those resulting from the circuit diagram, e.g. because of the finite resolution of the numerical values. In the standard it is said that the 33.06 nF capacitor may be adjusted or an active filter may be used.

Modeling at hand the circuit above and some calculus give this formula to get the amplitude response in dB for any given frequency value :

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_\mathrm{ITU}(f) = \frac{1.246332637532143\cdot10^{-4} \, f}{\sqrt{(h_1(f))^2 + (h_2(f))^2}} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{ITU}(f) = 18.2+20\log_{10}\left(R_\mathrm{ITU}(f)\right) }[/math]

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ h_1(f)=-4.737338981378384\cdot10^{-24} \, f^6 + 2.043828333606125\cdot10^{-15} \, f^4 - 1.363894795463638\cdot10^{-7} \, f^2 + 1 }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ h_2(f)=1.306612257412824\cdot10^{-19} \, f^5 - 2.118150887518656\cdot10^{-11} \, f^3 + 5.559488023498642\cdot10^{-4} \, f }[/math]

Tone-burst response requirements

5 kHz single bursts:

| Burst Duration (ms) | Steady Signal Reading (dB) |

|---|---|

| 200 | -1.9 |

| 100 | -3.3 |

| 50 | -4.6 |

| 20 | -5.7 |

| 10 | -6.4 |

| 5 | -8.0 |

| 2 | -11.5 |

| 1 | -15.4 |

Repetitive tone-burst response

5 ms, 5 kHz bursts at repetition rate:

| Number Of Bursts per Second (s−1) | Steady Signal Reading (dB) |

|---|---|

| 2 | -6.40 |

| 10 | -2.30 |

| 100 | -0.25 |

Unweighted measurement

Uses 22 Hz HPF and 22 kHz LPF 18 dB/decade or greater.

(Tables to be added)

See also

References

- ↑ "RECOMMENDATION ITU-R BS.468-4 - Measurement of audio-frequency noise voltage". International Telecommunication Union. http://www.itu.int/dms_pubrec/itu-r/rec/bs/R-REC-BS.468-4-198607-I!!PDF-E.pdf.

- ↑ "1910.95 - Occupational noise exposure. | Occupational Safety and Health Administration" (in en). https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/regulations/standardnumber/1910/1910.95.

- ↑ BBC Research Department Report - The assessment of noise in audio-frequency circuits. http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/rd/pubs/reports/1968-08.pdf

- ↑ "468 - Weighting in Detail". Lindos. https://lindos.co.uk/articles/itu-r-468-weighting-in-detail.

- ↑ "ISO 21727:2016(en) Cinematography — Method of measurement of perceived loudness of short duration motion-picture audio material". 2016. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:21727:ed-2:v1:en.

Further reading

- Audio Engineer's Reference Book, 2nd Ed 1999, edited Michael Talbot Smith, Focal Press

- An Introduction to the Psychology of Hearing 5th ed, Brian C. J. Moore, Elsevier Press

External links

|