Physics:Pedersen current

A Pedersen current is an electric current formed in the direction of the applied electric field when a conductive material with charge carriers is acted upon by an external electric field and an external magnetic field. Pedersen currents emerge in a material where the charge carriers collide with particles in the conductive material at approximately the same frequency as the gyratory frequency induced by the magnetic field. Pedersen currents are associated with a Pedersen conductivity[1] related to the applied magnetic field and the properties of the material.[2]

History

The first expression for the Pedersen conductivity was formulated by Peder Oluf Pedersen from Denmark in his 1927 work "The Propagation of Radio Waves along the Surface of the Earth and in the Atmosphere",[3][4][5] where he pointed out that the geomagnetic field means that the conductivity of the ionosphere is anisotropic.[6]

Physical explanation

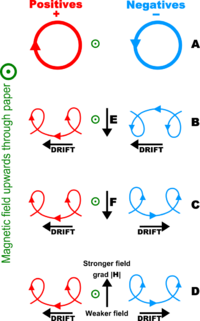

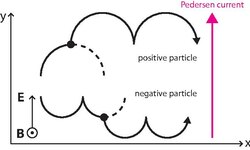

When a moving charge carrier in a conductor is under the influence of a magnetic field [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{B} }[/math], the carrier experiences a force perpendicular to the direction of motion and the magnetic field, resulting in a gyratory path, which is circular in the absence of any other external force. When an electric field [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E} }[/math] is applied in addition to the magnetic field and perpendicular to that field, this gyratory motion is driven by the electric field, leading to a net drift in the direction [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}\times \mathbf{B} }[/math] around the guiding center and a lack of mobility in the direction of the electric field. The charge carrier undergoes a helical motion whereby a charge carrier at rest acquires motion in the direction of the electric field according to Coulomb's law, gains a velocity perpendicular to the magnetic field, and subsequently is pushed in the direction [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v}\times \mathbf{B} }[/math] due to the Lorentz force (as [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v} }[/math] is in the direction of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{v}\times \mathbf{B} }[/math] is initially in the same direction as [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}\times \mathbf{B} }[/math].) The motion will then oscillate backwards against the electric field until it again reaches a velocity of zero in the direction of the electric field, before again being driven by the electric and magnetic fields, forming a helical path. As a result, in a vacuum, no net current is possible in the direction of the electric field. Likewise, when there is a dense material with a high frequency of collisions between the charge carriers and the conductive medium, mobility is very low and the charge carriers are basically stationary.[7]

For a positively charged particle, over the course of this helical path, there is a positive skew in the location distribution of the charge carrier in the direction of the electric field, such that at any given point in time a measurement of the location of the charge carrier will on average result in a positive change from original position in the direction of the electric potential. During a collision with another particle in the medium, the velocity of the charge carrier is randomized at the point of collision. This location of collision is likely to be a positive change in the direction of the electric field from the original location of the charge carrier. After the velocity is randomised, the charge carrier will then restart helical motion from a different original location. Overall, this results in a bulk movement in the direction of the electric field such that a current is able to flow, which is known as the Pedersen Current, with the associated Pedersen Conductivity reaching a maximum when the frequency of collisions is approximately equal to the gyratory frequency so that the charge carriers experience one collision for every gyration.[7]

The Pedersen conductivity is determined by the following equation:[2]

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\sigma}_P = \frac{en_e}B \left \{ \sum_i C_i \left [ \frac{\nu_{in} / \omega_i}{1 + (\nu_{in}^2 / \omega_i^2)} \right ] + \frac{\nu_e / \omega_e}{1 + (\nu_e^2 / \omega_e^2)} \right \} }[/math]

Where the electron density is [math]\displaystyle{ n_e }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is the magnetic field, [math]\displaystyle{ C_i }[/math] is the ion concentration for a given species, [math]\displaystyle{ \nu_{in} }[/math] is the collision frequency between ion species i and other particles, [math]\displaystyle{ \omega_i }[/math] is the gyrofrequency for that ion, [math]\displaystyle{ \nu_e }[/math] is the collision frequency for the electron, and [math]\displaystyle{ \omega_e }[/math] is the electron gyrofrequency.

A negative charge carrier undergoes a similar drift in the direction [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{E}\times \mathbf{B} }[/math], but moves in the opposite direction to a positive charge carrier, and undergoes helical motion such that there is a net negative skew in the distribution of position from the original position over the gyration, and as these particles are negatively charged they will also produce a positive contribution to the Pedersen current.[8]

Role in the Ionosphere

Pedersen currents play an important role in the ionosphere, especially in polar regions. In the ionospheric dynamo region near the poles, the ion density is low enough and the magnetic field high enough for the collision frequency to be comparable to the gyration frequency, and the Earth's magnetic field has a large component perpendicular to the horizontal electric field due to the high inclination of the field near the poles. As a result, Pedersen currents are a significant mechanism for charge carrier movement. The magnitude of the Pedersen current balances the drag on the ionospheric plasma due to ion‐neutral collisions.[9]

Pedersen currents in the ionosphere have a similar production mechanism to Hall currents, have a similar equation form for determining conductivity[10] and have a similar conductivity profile and conducitivity dependence on various factors. The Pedersen and Hall conductivities are maximised during daytime or in auroral regions at night, as they depend on plasma density, which in turn depends on auroral or solar ionization. The conductivities also vary by about 40% over the solar cycle, reaching a maximum conductivity around solar maximum.[1]

The Pedersen conductivity reaches a maximum in the ionosphere at an altitude of around 125 km.[8]

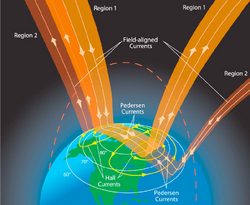

Pedersen currents flow between the Region 1 and Region 2 Birkeland current sheets (see the figure), completing the circuit of the flow of charge through the ionosphere (at a given local time, one region involves current entering the ionosphere along the geomagnetic field lines, and the other region involves current leaving the ionosphere.) There is also a Pedersen current that flows across the pole from the dawn side (local time 6:00) to the dusk side (local time 18:00) of the region 1 current sheet.

Electrons have also been shown to carry Pedersen currents in the D layer of the ionosphere.[8]

Joule heating

The Joule heating of the ionosphere, a major source of energy loss from the magnetosphere, is closely related to the Pedersen conductivity through the following relation:

[math]\displaystyle{ q_J = \mathbf{\sigma}_P (E - U_n \times B)^2 }[/math]

Where [math]\displaystyle{ q_J }[/math] is the Joule heating per unit volume, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbf{\sigma}_P }[/math] is the Pedersen conductivity, [math]\displaystyle{ E }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] are the electric and magnetic fields, and [math]\displaystyle{ U_n }[/math] is the neutral wind velocity.[2]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Richmond, Arthur D.; Gubbins, David (2007). Encyclopedia of Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 452–454. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4423-6_159. ISBN 9781402044236. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-1-4020-4423-6_159. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Sheng, Cheng; Deng, Yue; Yue, Xinan; Huang, Yanshi (2014-08-01). "Height-integrated Pedersen conductivity in both E and F regions from COSMIC observations". Journal of Atmospheric and Solar-Terrestrial Physics. Sun-Earth System Exploration: Moderate and Extreme Disturbances 115-116: 79–86. doi:10.1016/j.jastp.2013.12.013. ISSN 1364-6826. Bibcode: 2014JASTP.115...79S. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1364682613003313. Retrieved 2023-07-15.

- ↑ Pedersen, Peder Oluf (1927). "The Propagation of Radio Waves along the Surface of the Earth and in the Atmosphere". Danmarks Naturvidenskabelige Samfund A (15a).

- ↑ "Peder Oluf Pedersen". DTU. http://tekhist.pastperfectonline.com/person/E3FDBDA0-E5FB-4DD9-BD13-621050435859.

- ↑ "Person Record". DTU Historie. http://tekhist.pastperfectonline.com/person/E3FDBDA0-E5FB-4DD9-BD13-621050435859.

- ↑ Chapman, S. (1956-08-01). "The electrical conductivity of the ionosphere: A review". Il Nuovo Cimento (1955-1965) 4 (4): 1385–1412. doi:10.1007/BF02746310. ISSN 1827-6121. Bibcode: 1956NCim....4S1385C. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02746310. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Coxon, John Charles (2015). The role of Birkeland currents in the Dungey cycle (PhD thesis). University of Leicester.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Hosokawa, K.; Ogawa, Y. (2010). "Pedersen current carried by electrons in auroral D-region". Geophysical Research Letters 37 (18). doi:10.1029/2010GL044746. ISSN 1944-8007. Bibcode: 2010GeoRL..3718103H. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2010GL044746. Retrieved 2023-07-15.

- ↑ Cowley, Stanley W.H.; Gubbins, David (2007). Encyclopedia of Geomagnetism and Paleomagnetism. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 656–664. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-4423-6_205. ISBN 9781402044236. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-1-4020-4423-6_205. Retrieved 16 July 2023.

- ↑ Evans, D. S.; Maynard, N. C.; Trøim, J.; Jacobsen, T.; Egeland, A. (1977). "Auroral vector electric field and particle comparisons, 2, Electrodynamics of an arc". Journal of Geophysical Research 82 (16): 2235–2249. doi:10.1029/JA082i016p02235. ISSN 2156-2202. Bibcode: 1977JGR....82.2235E. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/JA082i016p02235. Retrieved 2023-07-16.

|