Social:Latgalian language

| Latgalian | |

|---|---|

| latgalīšu volūda | |

| Native to | Latvia, Russia [citation needed] |

| Region | Latgalia, Selonia, Vidzeme, Siberia, Bashkiriya [citation needed] |

| Ethnicity | Modern Latgalians |

Native speakers | 200,000 (2009)e25 |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

| Latin script (Latgalian alphabet)[1] | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | ltg |

| Glottolog | east2282[2] |

| Linguasphere | 54-AAB-ad Latgale |

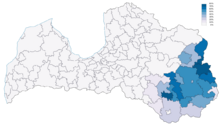

Use of Latgalian in everyday communication in 2011 by municipalities of Latvia | |

Latgalian is classified as Vulnerable by the UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger | |

Latgalian (latgalīšu volūda, Latvian: latgaliešu valoda) is a dialect of Latvian language or, as the Latvian language law states, a "historical form of Latvian".[3] It is mostly spoken in Latgale, the eastern part of Latvia.[4] Its standardized form is recognized and protected as a "historical language of Latvia" (vēsturiska valoda Latvijā) under national law.[5] The 2011 Latvian census established that 8.8% of Latvia's inhabitants, or 164,500 people, speak Latgalian daily. 97,600 of them live in Latgale, 29,400 in Riga and 14,400 in the Riga Planning Region.[6]

History

Originally Latgalians were a tribe living in modern Vidzeme and Latgale. It is thought that they spoke the Latvian language, which later spread through the rest of modern Latvia, absorbing features of the Old Curonian, Semigallian, Selonian and Livonian languages. The Latgale area became politically separated during the Polish–Swedish wars, remaining part of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as the Inflanty Voivodeship, while the rest of the Latvians lived in lands dominated by Baltic German nobility. Both centuries of separate development and the influence of different prestige languages likely contributed to the development of modern Latgalian as little bit distinct from the language spoken in Vidzeme and other parts of Latvia. Also Latgalian has the many sheets and it's not a one form of dialect.

The modern Latgalian literary tradition started to develop in the 18th century from vernaculars spoken by Latvians in the eastern part of Latvia. The first surviving book published in Latgalian is "Evangelia toto anno" (Gospels for the whole year) in 1753. The first systems of orthography were borrowed from Polish and used Antiqua letters. It was very different from the German-influenced orthography, usually written in Blackletter or Gothic script, used for the Latvian language in the rest of Latvia. Many Latgalian books in the late 18th and early 19th century were authored by Jesuit priests, who came from various European countries to Latgale as the north-eastern outpost of the Roman Catholic religion; their writings included religious literature, calendars, and poetry.

Publishing books in the Latgalian language along with the Lithuanian was forbidden from 1865 to 1904. The ban on using Latin letters in this part of the Russian Empire followed immediately after the January Uprising, where insurgents in Poland , Lithuania, and Latgale had challenged the czarist rule. During the ban, only a limited number of smuggled Catholic religious texts and some hand-written literature were available, e.g. calendars written by the self-educated peasant Andryvs Jūrdžys (ltg).

After the repeal of the ban in 1904, there was a quick rebirth of the Latgalian literary tradition; first newspapers, textbooks, and grammar appeared. In 1918 Latgale became part of the newly created Latvian state. From 1920 to 1934 the two literary traditions of Latvians developed in parallel. A notable achievement during this period was the original translation of the New Testament into Latgalian by the priest and scholar Aloizijs Broks (ltg), published in Aglona in 1933. After the coup staged by Kārlis Ulmanis in 1934, the subject of the Latgalian dialect was removed from the school curriculum and was invalidated for use in state institutions; this was as part of an effort to standardize Latvian language usage. Latgalian survived as a spoken language in Soviet Latvia (1940–1991) while printed literature in Latgalian virtually ceased between 1959 and 1989. In emigration, some Latgalian intellectuals continued to publish books and studies of the Latgalian language, most notably Mikeļs Bukšs (ltg); see the bibliography.

Since the restoration of Latvian independence, there has been a noticeable increase in interest in the Latgalian language and cultural heritage. It is taught as an optional subject in some universities; in Rēzekne the Publishing House of Latgalian Culture Centre (Latgales kultūras centra izdevniecība)[what language is this?] led by Jānis Elksnis, prints both old and new books in Latgalian.

In 1992, Juris Cibuļs together with Lidija Leikuma (ltg) published one of the first Latgalian alphabet books after the restoration of the language.

In the 21st century, the Latgalian language has become more visible in Latvia's cultural life. Apart from its preservation movements, Latgalian can be more often heard in different interviews on the national TV channels, and there are modern rock groups such as Borowa MC and Dabasu Durovys singing in Latgalian who have had moderate success also throughout the country. Today, Latgalian is also found in written form on public signs, such as some street names (e.g. in Kārsava) and shop signs, evidences of growing use in the linguistic landscape.[7]

In November 2021, the first state-approved road sign in Latvian and Latgalian was placed on the border of Balvi Municipality, with others being gradually installed in other locations in Latgale. Similarly, signs with Livonian are also being placed.[8][9]

Classification

Latgalian is a member of the East Baltic branch of the Baltic group of languages, in the family of Indo-European languages. The branch also includes the standard form of Latvian and other Baltic languages like Samogitian and Lithuanian. Latgalian is a moderately inflected language; the number of verb and noun forms is characteristic of many other Baltic and Slavic languages (see Inflection in Baltic Languages).

Geographic distribution

Latgalian is spoken by about 150,000 people,Template:Atlas UNESCO mainly in Latgale, Latvia; there are small Latgalian-speaking communities in Siberia, Russia , created as a result of the emigration of Latgalians at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries[10] and the massive Soviet deportations from Latvia.

Official status

Between 1920 and 1934 Latgalian was used in local government and education in Latgale. Now Latgalian is not used as an official language anywhere in Latvia. It is formally protected by the Latvian Language Law stating that "The Latvian State ensures the preservation, protection, and development of the Latgalian literary language as a historical variant of the Latvian language" (§3.4).[5] The law regards Latgalian and Standard Literary Latvian as two equal variants of the same Latvian language. Even though such legal status allows usage of Latgalian in state affairs and education spheres, it still happens quite rarely.

There is a state-supported orthography commission of the Latgalian language.

Dialects

Latgalian speakers can be classified into three main groups – Northern, Central, and Southern. These three groups of local accents are entirely mutually intelligible and characterized only by minor changes in vowels, diphthongs, and some inflexion endings. The regional accents of central Latgale (such as those spoken in the towns and rural municipalities of Juosmuiža, Vuorkova, Vydsmuiža, Viļāni, Sakstygols, Ūzulaine, Makašāni, Drycāni, Gaigalova, Bierži, Tiļža, and Nautrāni) form the phonetical basis of the modern standard Latgalian language. The literature of the 18th century was more influenced by the Southern accents of Latgalian.

Alphabet

The Latgalian language uses an alphabet with 35 letters. Its orthography is similar to literary Latvian orthography, but has two additional letters: ⟨y⟩ represents [ɨ]), an allophone of /i/ which is absent in standard Latvian. The letter ⟨ō⟩ survives from the pre-1957 Latvian orthography, but is used less during modern times in Latgalian and is being replaced by two letters ⟨uo⟩ that represent the same sound.[11]

| Upper case | Lower case | Pronunciation |

|---|---|---|

| A | a | /a/ |

| Ā | ā | /aː/ |

| B | b | /b/ |

| C | c | /t͡s/ |

| Č | č | /t͡ʃ/ |

| D | d | /d/ |

| E | e | /ɛ/ |

| Ē | ē | /ɛː/ |

| F | f | /f/ |

| G | g | /ɡ/ |

| Ģ | ģ | /ɡʲ/ |

| H | h | /x/ |

| I | i | /i/ |

| Y | y | /ɨ/ |

| Ī | ī | /iː/ |

| J | j | /j/ |

| K | k | /k/ |

| Ķ | ķ | /kʲ/ |

| L | l | /l/ |

| Ļ | ļ | /lʲ/ |

| M | m | /m/ |

| N | n | /n/ |

| Ņ | ņ | /nʲ/ |

| O | o | /ɔ/ |

| Ō | ō | /ɔː/ |

| P | p | /p/ |

| R | r | /r/ |

| S | s | /s/ |

| Š | š | /ʃ/ |

| T | t | /t/ |

| U | u | /u/ |

| Ū | ū | /uː/ |

| V | v | /v/ |

| Z | z | /z/ |

| Ž | ž | /ʒ/ |

The IETF language tags have registered subtags for the 1929 orthography (ltg-ltg1929) and the 2007 orthography (ltg-ltg2007).[12]

Language examples

Poem of Armands Kūceņš

Tik skrytuļam ruodīs: iz vītys jis grīžās,

A brauciejam breinums, kai tuoli ceļš aizvess,

Tai vuorpsteite cīši pret sprāduoju paušās,

Jei naatteik – vacei gi dzejis gols zvaigznēs.

Pruots naguorbej ramu, juos lepneibu grūžoj,

Vys jamās pa sovam ļauds pasauli puormeit,

Bet nak jau sevkuram vīns kuorsynoj myužu

I ramaņu jumtus līk īguodu kuormim.

Na vysim tai sadar kai kuošam ar speini,

Sirds narymst i nabeidz par sātmalim tēmēt,

A pruots rauga skaitejs pa rokstaudža zeimem,

Kai riedeits, kod saulei vēļ vaiņuku jēme.

Lord's Prayer

Tāvs myusu, kas esi debesīs,

svēteits lai tūp Tovs vōrds.

Lai atnōk Tova vaļsteiba.

Tova vaļa lai nūteik, kai debesīs,

tai ari vērs zemes.

Myusu ikdīneiškū maizi dūd mums šudiņ.

Un atlaid mums myusu porōdus,

kai ari mes atlaižam sovim porōdnīkim.

Un naīved myusu kārdynōšonā,

bet izglōb myusus nu ļauna Amen.

Phrasebook

| Latgalian | Latvian | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Vasals! | Sveiks! | Hi! (literally, 'hale and hearty!'; Sveiks is more common as 'hi' in Latvian but has a different meaning) |

| Loba dīna! | Labdien! | Hello, Good day! |

| Muns vuords Eugeņs. | Mans vārds ir Eugeņs. | My name is Eugene. |

| Šudiņ breineiga dīna! | Šodien ir brīnišķīga diena! | Today is a wonderful/beautiful day! |

| Vīns, div, treis, niu tu breivs! | Viens, divi, trīs, nu tu esi brīvs! | One, two, three, now you are free! (counting game for children) |

| Asu aizjimts itamā šaļtī! | Esmu aizņemts šobrīd! | I am busy at the moment! |

| Es tevi mīļoju! | Es tevi mīlu! | I love you! |

| Asu nu Latgolys. | Esmu no Latgales. | I am from Latgalia. |

| As īšu iz sātu. | Es iešu mājās. | I will go home. (Note: sēta in Latvian means the courtyard to a homestead, also homestead; so a more rural/agrarian sense of "home" in the Latgalian than in the Latvian mājās, which is more evocative of a house.) |

| Maņ pateik vuiceitīs (muoceitīs). | Man patīk mācīties. | I like to learn. (Note: this marked difference between Latgalian and Latvian is quite typical. The set of examples here are quite similar because they relate to basic concepts.) |

Common words in Latgalian and Lithuanian, different from Latvian

Note the impact of foreign influences on Latvian (German in Kurzeme and Vidzeme, Polish and Lithuanian in Latgale).

| English | Latvian | Latgalian | Lithuanian | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| around | apkārt | apleik | aplink | aplinkus in Latvian means "indirectly" |

| always | vienmēr | vysod | visad(a) | |

| every day | ikdienas | kasdīnys | kasdienis | |

| he | viņš/šis | jis | jis | šis in Lithuanian means 'this' |

| urgent | steidzams | skubeigs | skubus | skubīgs has the same meaning in Latvian, but is rarely used |

| to interrogate/to ask | taujāt/izjautāt | klaust | klausti | klausīties in Latvian is 'to listen'; klau! means 'hey!'; klaušināt means 'to ask several people' |

| girl/maid | meita/meitene | mārga | mergina/merga | meita in Latvian is used more often as 'daughter' while meitene means 'girl' exclusively |

| kerchief | lakatiņš | skareņa | skarelė | |

| dress/frock | kleita | sukne | suknelė | kleita in Latvian is adapted from the German das Kleid; any native term has been lost. Latgalian and Lithuanian – comp. Polish suknia. |

| top/apical | galotne/virsotne | viersyune | viršūnė | |

| pillar/column | stabs | stulps | stulpas | stulpiņi (diminutive, plural for stulps) in Latvian is preserved as 'leggings' |

| to read | lasīt | skaiteit | skaityti | skaitīt in Latvian means 'to count'; noskaitīt is 'to recite' |

| to come | nākt | atīt | ateiti | atiet in Latvian means 'to depart' (the root word iet means 'to go') |

| row, range, or line | rinda | aiļa | eilė | aile in Latvian means row in very narrow sense – it refers to space between two lines |

| to sit down | apsēsties | atsasēst | atsisėsti | |

| to answer | atbildēt | atsaceit | atsakyti | atsacīt in Latvian means 'to reject, refuse' (and to do it quickly and sharply); atsisakyti can also be used with this meaning in Lithuanian |

| to torture | mocīt | komuot | kamuoti | |

| to die (about animals) | nosprāgt | nūgaist | nugaišti | |

| to squeeze | maidzīt | maidzeit | maigyti | |

| to catch a cold | saaukstēties | puorsaļt | peršalti | pārsalt in Latvian means 'to freeze overly' (near death) |

| cold | auksts | solts | šaltis | auksts is more common in Latvian for 'cold' than salts, which is a chilling cold |

| mistake | kļūda | klaida | klaida | |

| page | lappuse | puslopa | puslapis | compound word; in Latvian the order is 'leaf'+'side', reverse of the order in Latgalian and Lithuanian |

| down/downward | lejup | zamyn | žemyn | zemu in Latvian means 'low' |

| and/also | un | i | ir | un and arī are common usage in Latvian; i is archaic found mainly in folk songs and poetry |

| to settle in | iekārtoties | īsataiseit | įsitaisyti/įsikurti | |

| family | ģimene | saime | šeima | ģimene is used in Latvian for the core family; saime denotes extended family and household, for example, saimnieks, saimniece are 'master' and 'mistress', respectively, of the household, while in Lithuanian it is giminė, which is used for extended family |

| homeland | tēvija | tāvaine | tėvynė | |

| east | austrumi | reiti | rytai | rīti is a less common, poetic form in Latvian |

| west | rietumi | vokori | vakarai | vakari is a less common, poetic form in Latvian |

| to stand up | piecelties | atsastuot | atsistoti | |

| to sore | sūrstēt | pierkšēt | perštėti | |

| scissors | šķēres | zirklis | žirklės | šķēres in Latvian is adapted from the German die Schere, dzirkles refers to shears |

| to forgive | piedot | atlaist | atleisti | |

| owl | pūce | palāda | pelėda | |

| toad | krupis | rupucs | rupūžė | |

| fear | bailes | baime | baimė | |

| last name/surname | uzvārds | pavuorde | pavardė | |

| smith | kalējs | kaļvs | kalvis | |

| to clatter | rībēt/skrabēt | brazdēt | brazdėti | |

| to perish | iet bojā | propuļt | prapulti | |

| on horseback | jāšus | raitu | raitas | |

| inside | iekšā | vydā | viduj | vidū in Latvian means 'in the middle' |

| to notice | ievērot | ītiemēt | įsidėmėti | |

| a little | mazliet | drupeiti | truputį | |

| to bore/to become boring | apnikt | atbuost/atsabuost | atsibosti | |

| to undress | noģērbties | nūsaviļkt | nusivilkti | |

| swamp | dumbrājs/muklājs | liuņs | liūnas | |

| kidney | niere | eiksts | inkstas | niere in Latvian is adapted from German and has replaced the native īkstis |

| to poke | bakstīt | badeit | badyti | |

| to hover | plivināties apkārt | laksteit | lakstyti | |

| to bathe | peldēties | mauduotīs | maudytis | |

| clover | āboliņš | duobuls | dobilas | |

| first of all | vispirms | pyrma | (visų) pirma/pirmiausiai | |

| suddenly | pēkšņi | ūmai | ūmai | |

| to stretch (oneself) | staipīties/gorīties | rūzeitīs | rąžytis | |

| to detect | uziet/konstatēt | aptikt | aptikti | |

| to snatch | pakampt | sačupt | sučiupti | pagauti in Lithuanian means 'to catch' |

| to grope | taustīties | čupinētīs | čiupinėtis | |

| church holiday | baznīcas svētki | atlaidys | atlaidai | |

| variable (dates) | mainīgi (datumi) | cylojamuos (dīnys) | kilnojamos (dienos) | |

| remotely | attālu | atostai | atstu/atokiai | |

| to make faces | vaikstīties | šaipeitīs | vaipytis | |

| to shell | lobīt | gaļdeit | gliaudyti | |

| to thresh (by beating) | kult (dauzot) | bluokšt | blokšti | |

| to break (about glass) | plīst (par stiklu) | dyuzt | dūžti |

See also

- Latgalian Wikipedia

- Samogitian language

- Võro language

- Livonian language

References

- ↑ Template:E21

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "East Latvian". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/east2282.

- ↑ https://likumi.lv/doc.php?id=14740 Valsts valodas likums], Article 3.

- ↑ Druviete, Ina (22 July 2001). "Recenzija par pētījumu "Valodas loma reģiona attīstībā"" (in lv). Politika.lv. http://politika.lv/article/recenzija-par-petijumu-valodas-loma-regiona-attistiba.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Official Language Law". https://likumi.lv/ta/en/en/id/14740-official-language-law.

- ↑ "Tautas skaitīšana: Latgalē trešā daļa iedzīvotāju ikdienā lieto latgaliešu valodu" (in lv). 6 July 2012. http://www.lsm.lv/lv/raksts/latvija/zinas/tautas-skaitiishana-latgale-tresha-dalja-iedziivotaju-ikdiena-li.a6091/.

- ↑ Lazdiņa, Sanita (2013). "A Transition from Spontaneity to Planning? Economic Values and Educational Policies in the Process of Revitalizing the Regional Language of Latgalian (Latvia)" (in en). Current Issues in Language Planning 14 (3–04): 382–402. doi:10.1080/14664208.2013.840949.

- ↑ "Balvu novadā ceļazīmes arī latgaliešu rakstu valodā" (in lv). 2021-11-24. https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/zinas/latvija/balvu-novada-celazimes-ari-latgaliesu-rakstu-valoda.a431523/.

- ↑ Ozola-Balode, Zanda (2023-01-27). "Talsu novada nosaukums tagad arī lībiešu valodā; šādi uzraksti būs vismaz 14 piekrastes ciemos" (in lv). https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/zinas/latvija/talsu-novada-nosaukums-tagad-ari-libiesu-valoda-sadi-uzraksti-bus-vismaz-14-piekrastes-ciemos.a493676/.

- ↑ Sanita Reinsone, LATGALIAN EMIGRANTS IN SIBERIA: CONTRADICTING IMAGES, doi:10.7592/FEJF2014.58.reinsone

- ↑ lakuga.lv, Portals (2018-09-06). "UO i Ō. Kurs pareizuoks?" (in en-GB). https://www.lakuga.lv/2018/09/06/uo-i-o-kurs-pareizuoks/.

- ↑ "Language Subtag Registry" (text). IANA. 2022-08-08. https://www.iana.org/assignments/language-subtag-registry/language-subtag-registry.

External links

| latgaļu edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Latvian–Latgalian Dictionary

- Sanita Lazdiņa, Heiko F. Marten: Latgalian in Latvia: A Continuous Struggle for Political Recognition. In: Journal on Ethnopolitics and Minority Issues in Europe

- The Two Literary Traditions of Latvians

- Some facts about Latgalian language

- The Grammar of Latgalian Language (in Latvian, PDF document)

|