Social:Ge'ez

| Ge'ez | |

|---|---|

| ግዕዝ Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | |

| |

| Native to | Ethiopia, Eritrea |

| Extinct | Estimates range from the 4th century BC[1] to sometime before the 10th century.[2] Remains in use as a liturgical language.[3] |

Afro-Asiatic

| |

| Ge'ez script | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Liturgical language of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, Ethiopian Catholic Church,[3] Eritrean Catholic Church and Beta Israel[4] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | gez |

| ISO 639-3 | gez |

| Glottolog | geez1241[5] |

Ge'ez (/ˈɡiːɛz/;[6][7] ግዕዝ, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. Template:IPA-gez; also transliterated Gi'iz) is an ancient South Semitic language of the Ethiosemitic branch. The language originates from the region encompassing northern Ethiopia and southern Eritrea in the Horn of Africa.

Today, Ge'ez is used only as the main language of liturgy of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo churches, the Ethiopian and Eritrean Catholic churches, and the Beta Israel Jewish community. However, in Ethiopia, Amharic or other local languages, and in Eritrea and Ethiopia's Tigray Region, Tigrinya may be used for sermons. Amharic, Tigrinya, and Tigre are closely related to Ge'ez.[8][9]

The closest living languages to Ge'ez are Tigre and Tigrinya with lexical similarity at 71% and 68%, respectively.[10] Some linguists do not believe that Ge'ez constitutes a common ancestor of modern Ethiosemitic languages, but that Ge'ez became a separate language early on from another hypothetical unattested language,[11] which can be seen as an extinct sister language of Amharic, Tigre and Tigrinya.[12] The foremost Ethiopian experts such as Amsalu Aklilu point to the vast proportion of inherited nouns that are unchanged, and even spelled identically in both Ge'ez and Amharic (and to a lesser degree, Tigrinya).[13]

Phonology

Vowels

- a /æ/ < Proto-Semitic *a; later e

- u /u/ < Proto-Semitic *ū

- i /i/ < Proto-Semitic *ī

- ā /aː/ < Proto-Semitic *ā; later a

- e /e/ < Proto-Semitic *ay

- ə /ɨ/ < Proto-Semitic *i, *u

- o /o/ < Proto-Semitic *aw

Also transliterated as ä, ū/û, ī/î, a, ē/ê, e/i, ō/ô.

Consonants

Transliteration

Ge'ez is transliterated according to the following system:

| translit. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ge'ez | ሀ | ለ | ሐ | መ | ሠ | ረ | ሰ | ሸ | ቀ | በ | ተ | ኀ | ነ | አ |

| translit. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ge'ez | ከ | ወ | ዐ | ዘ | የ | ደ | ገ | ጠ | ጰ | ጸ | ፀ | ፈ | ፐ |

Because Ge'ez is no longer a spoken language, the pronunciation of some consonants is not completely certain. Gragg (1997:244) writes "The consonants corresponding to the graphemes Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (Ge'ez ሠ) and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (Ge'ez ፀ) have merged with ሰ and ጸ respectively in the phonological system represented by the traditional pronunciation—and indeed in all modern Ethiopian Semitic. ... There is, however, no evidence either in the tradition or in Ethiopian Semitic [for] what value these consonants may have had in Ge'ez."

A similar problem is found for the consonant transliterated Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.. Gragg (1997:245) notes that it corresponds in etymology to velar or uvular fricatives in other Semitic languages, but it was pronounced exactly the same as Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. in the traditional pronunciation. Though the use of a different letter shows that it must originally have had some other pronunciation, what that pronunciation was is not certain. The chart below lists /ɬ/ and /ɬʼ/ as possible values for Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (ሠ) and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (ፀ) respectively. It also lists /χ/ as a possible value for Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (ኀ). These values are tentative, but based on the reconstructed Proto-Semitic consonants that they are descended from.

Phonemes of Ge'ez

In the chart below, IPA values are shown. When transcription is different from the IPA, the character is shown in angular brackets. Question marks follow phonemes whose interpretation is controversial (as explained in the preceding section).

| Labial | Dental | Palatal | Velar, Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | lateral | plain | labialized | ||||||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t | k | kʷ | ʔ ⟨’⟩ | |||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ɡʷ | |||||

| emphatic1 | pʼ ⟨p̣⟩ | tʼ ⟨ṭ⟩ | kʼ ⟨ḳ⟩ | kʷʼ ⟨ḳʷ⟩ | |||||

| Affricate | emphatic | t͡sʼ ⟨ṣ⟩ | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ɬ? ⟨ś⟩ | χ? ⟨ḫ⟩ | ħ ⟨ḥ⟩ | h | ||

| voiced | z | ʕ ⟨‘⟩ | |||||||

| emphatic | ɬʼ? ⟨ḍ⟩ | ||||||||

| Trill | r | ||||||||

| Approximant | l | j ⟨y⟩ | w | ||||||

- In Ge'ez, emphatic consonants are phonetically ejectives. As is the case with Arabic, emphatic velars may actually be phonetically uvular ([q] and [qʷ]).

Ge'ez consonants in relation to Proto-Semitic

Ge'ez consonants have a triple opposition between voiceless, voiced, and ejective (or emphatic) obstruents. The Proto-Semitic "emphasis" in Ge'ez has been generalized to include emphatic p̣. Ge'ez has phonologized labiovelars, descending from Proto-Semitic biphonemes. Ge'ez ś ሠ Sawt (in Amharic, also called śe-nigūś, i.e. the se letter used for spelling the word nigūś "king") is reconstructed as descended from a Proto-Semitic voiceless lateral fricative [ɬ]. Like Arabic,[clarification needed] Ge'ez merged Proto-Semitic š and s in ሰ (also called se-isat: the se letter used for spelling the word isāt "fire"). Apart from this, Ge'ez phonology is comparably conservative; the only other Proto-Semitic phonological contrasts lost may be the interdental fricatives and ghayn.

Morphology

Nouns

Ge'ez distinguishes two genders, masculine and feminine, which in certain words is marked with the suffix -t. These are less strongly distinguished than in other Semitic languages, in that many nouns not denoting persons can be used in either gender: in translated Christian texts there is a tendency for nouns to follow the gender of the noun with a corresponding meaning in Greek.[14] There are two numbers, singular and plural. The plural can be constructed either by suffixing -āt to a word, or by internal plural.

- Plural using suffix: ʿāmat – ʿāmatāt 'year(s)', māy – māyāt 'water(s)' (Note: In contrast to adjectives and other Semitic languages, the -āt suffix can be used for constructing the plural of both genders).

- Internal plural: bet – ʾābyāt 'house, houses'; qərnəb – qarānəbt 'eyelid, eyelids'.

Nouns also have two cases, the nominative which is not marked and the accusative which is marked with final -a (e.g. bet, bet-a).

Internal plural

Internal plurals follow certain patterns. Triconsonantal nouns follow one of the following patterns.

| Patterns of internal plural for triconsonantal nouns.[2][15] (C=Consonant, V=Vowel) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern | Singular | Meaning | Plural |

| āCCāC | |||

| ləbs | 'garment' | ālbās | |

| faras | 'horse' | āfrās | |

| bet | 'house' | ābyāt | |

| tzom | 'fast' | ātzwām | |

| səm | 'name' | āsmāt | |

| āCCuC | |||

| hāgar | 'country' | āhgur | |

| āCCəCt | |||

| rəʾs | 'head' | arʾəst | |

| gabr | 'servant, slave' | āgbərt | |

| āCāCə(t) | |||

| bagʾ | 'sheep' | ābāgəʾ | |

| gānen | 'devil' | āgānənt | |

| CVCaC | |||

| əzn | 'ear' | ā'zan | |

| əgr | 'foot' | ā'gar | |

| CVCaw | |||

| əd | 'hand' | ā'daw | |

| ab | 'father' | ābaw | |

| əḫʷ | 'brother' | āḫaw | |

Quadriconsonantal and some triconsonantal nouns follow the following pattern. Triconsonantal nouns that take this pattern must have at least one long vowel[2]

| Patterns of internal plural for quadriconsonantal nouns.[2][15] (C=Consonant, V=Vowel) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pattern | Singular | Meaning | Plural |

| CaCāCəC(t) | |||

| dəngəl | 'virgin' | danāgəl | |

| masfən | 'prince' | masāfənt | |

| kokab | 'star' | kawākəbt | |

| qasis | 'priest' | qasāwəst | |

Pronominal morphology

| Number | Person | Isolated personal pronoun | Pronominal suffix | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With noun | With verb | |||

| Singular | 1. | ʾāna | -ya | -ni |

| 2. masculine | ʾānta | -ka | ||

| 2. feminine | ʾānti | -ki | ||

| 3. masculine | wəʾətu | -(h)u | ||

| 3. feminine | yəʾəti | -(h)a | ||

| Plural | 1. | nəḥna | -na | |

| 2. masculine | ʾāntəmu | -kəmu | ||

| 2. feminine | ʾāntən | -kən | ||

| 3. masculine | wəʾətomu / əmuntu | -(h)omu | ||

| 3. feminine | wəʾəton / əmāntu | -(h)on | ||

Verb conjugation

| Person | Perfect qatal-nn |

Imperfect | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicative -qattəl |

Jussive -qtəl | |||

| Singular | 1. | qatal-ku | ʾə-qattəl | ʾə-qtəl |

| 2. m. | qatal-ka | tə-qattəl | tə-qtəl | |

| 2. f. | qatal-ki | tə-qattəl-i | tə-qtəl-i | |

| 3. m. | qatal-a | yə-qattəl | yə-qtəl | |

| 3. f. | qatal-at | tə-qattəl | tə-qtəl | |

| Plural | 1. | qatal-na | nə-qattəl | nə-qtəl |

| 2. m. | qatal-kəmmu | tə-qattəl-u | tə-qtəl-u | |

| 2. f. | qatal-kən | tə-qattəl-ā | tə-qtəl-ā | |

| 3. m. | qatal-u | yə-qattəl-u | yə-qtəl-u | |

| 3. f. | qatal-ā | yə-qattəl-ā | yə-qtəl-ā | |

Syntax

Noun phrases

Noun phrases have the following overall order: (demonstratives) noun (adjective)-(relative clause)

| ba-za: | hagar | |

| in-this:f | city | |

| in this city | ||

| nəguś | kəbur | |

| king | glorious | |

| the glorious king | ||

Adjectives and determiners agree with the noun in gender and number:

| za:ti | nəgəśt | kəbərt |

| this:fem | queen | glorious:fem |

| this glorious queen | ||

| 'əllu | nagaśt | kəbura:n |

| these:mpl | kings | glorious:pl |

| these glorious kings | ||

Relative clauses are introduced by a pronoun which agrees in gender and number with the preceding noun:

| bə'si | za=qatal-əww-o | la=wald-o | |

| man | which:masc=kill-3mp-3ms | to=son=3ms | |

| the man whose son they killed | |||

As in many Semitic languages, possession by a noun phrase is shown through the construct state. In Ge'ez, this is formed by suffixing /-a/ to the possessed noun, which is followed by the possessor, as in the following examples (Lambdin 1978:23):

| wald-a | nəguś |

| son-construct | king |

| the son of the king | |

| səm-a | mal'ak |

| name-construct | angel |

| the name of the angel | |

Possession by a pronoun is indicated by a suffix on the possessed noun, as seen in the following table:

| Possessor | affix |

|---|---|

| 1sg 'my' | -əya |

| 2msg 'your (masc)' | -əka |

| 2fsg 'your (fem)' | -əki |

| 3msg 'his' | -u |

| 3fsg 'her' | -a: |

| 1pl 'our' | -əna |

| 2mpl 'your (masc. plur)' | -əkəma |

| 2fpl 'your (fem. plur)' | -əkən |

| 3mpl 'their (masc)' | -omu |

| 3fpl 'their (fem)' | -on |

The following examples show a few nouns with pronominal possessors:

| səm-əya | səm-u |

| name-1sg | name-3sg |

| my name | his name |

Another common way of indicating possession by a noun phrase combines the pronominal suffix on a noun with the possessor preceded by the preposition /la=/ 'to, for' (Lambdin 1978:44):

| səm-u | la = neguś |

| name-3sg | to = king |

| 'the king's name; the name of the king' | |

Lambdin (1978:45) notes that in comparison to the construct state, this kind of possession is only possible when the possessor is definite and specific. Lambdin also notes that the construct state is the unmarked form of possession in Ge'ez.

Prepositional phrases

Ge'ez is a prepositional language, as in the following example (Lambdin 1978:16):

| wəsta | hagar |

| to | city |

| to the city | |

There are three special prepositions, /ba=/ 'in, with', /la=/ 'to, for', /'əm=/ 'from', which always appear as proclitics on the following noun, as in the following examples:

| 'əm = hagar | |

| from = city | |

| from the city | |

| ba=hagar | |

| in = city | |

| in the city | |

These proclitic prepositions in Ge'ez are similar to the inseparable prepositions in Hebrew.

Sentences

The normal word order for declarative sentences is VSO. Objects of verbs show accusative case marked with the suffix /-a/:

| Takal-a | bə'si | ʕətsʼ-a |

| plant-3ms | man | tree-acc |

| The man planted a tree | ||

Questions with a wh-word ('who', 'what', etc.) show the question word at the beginning of the sentence:

| 'Ayya | hagar | ḥanaṣ-u |

| which | city | flee-3pl |

| Which city did they flee? | ||

Negation

The common way of negation is the prefix ʾi- which descends from ʾey- (which is attested in Axum inscriptions) from ʾay from Proto-Semitic *ʾal by palatalization.[2] It is prefixed to verbs as follows:

| nəḥna | ʾi-nəkl | ḥawira |

| we | (we) cannot | go |

| we cannot go | ||

Writing system

Ge'ez is written with Ethiopic or the Ge'ez abugida, a script that was originally developed specifically for this language. In languages that use it, such as Amharic and Tigrinya, the script is called Script error: The function "transl" does not exist., which means script or alphabet.

Ge'ez is read from left to right.

The Ge'ez script has been adapted to write other languages, usually ones that are also Semitic. The most widespread use is for Amharic in Ethiopia and Tigrinya in Eritrea and Ethiopia. It is also used for Sebatbeit, Meʻen, Agew and most other languages of Ethiopia. In Eritrea it is used for Tigre, and it is often used for Bilen, a Cushitic language. Some other languages in the Horn of Africa, such as Oromo, used to be written using Ge'ez but have switched to Latin-based alphabets. It also uses 4 symbols for labialized velar consonants, which are variants of the non-labialized velar consonants:

| Basic sign | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ቀ | ኀ | ከ | ገ | |

| Labialized variant | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. | Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. |

| ቈ | ኈ | ኰ | ጐ |

History and literature

Although it is often said that Ge'ez literature is dominated by the Bible including the Deuterocanonical books, in fact there are many medieval and early modern original texts in the language. Most of its important works are also the literature of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, which include Christian liturgy (service books, prayers, hymns), hagiographies, and Patristic literature. For instance, around 200 texts were written about indigenous Ethiopian saints from the fourteenth through the nineteenth century. This religious orientation of Ge'ez literature was a result of traditional education being the responsibility of priests and monks. "The Church thus constituted the custodian of the nation's culture", notes Richard Pankhurst, and describes the traditional education as follows:

Traditional education was largely biblical. It began with the learning of the alphabet, or more properly, syllabary... The student's second grade comprised the memorization of the first chapter of the first Epistle General of St. John in Geez. The study of writing would probably also begin at this time, and particularly in more modern times some arithmetic might be added. In the third stage the Acts of the Apostles were studied, while certain prayers were also learnt, and writing and arithmetic continued. ... The fourth stage began with the study of the Psalms of David and was considered an important landmark in a child's education, being celebrated by the parents with a feast to which the teacher, father confessor, relatives and neighbours were invited. A boy who had reached this stage would moreover usually be able to write, and might act as a letter writer.[16]

However, works of history and chronography, ecclesiastical and civil law, philology, medicine, and letters were also written in Ge'ez.[17]

The Ethiopian collection in the British Library comprises some 800 manuscripts dating from the 15th to the 20th centuries, notably including magical and divinatory scrolls, and illuminated manuscripts of the 16th to 17th centuries. It was initiated by a donation of 74 codices by the Church of England Missionary Society in the 1830s and 1840s, and substantially expanded by 349 codices, looted by the British from the Emperor Tewodros II's capital at Magdala in the 1868 Expedition to Abyssinia. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City has at least two illuminated manuscripts in Ge'ez.

Origins

The Ge'ez language is classified as a South Semitic language. It evolved from an earlier proto-Ethio-Semitic ancestor used to write royal inscriptions of the kingdom of Dʿmt in the Epigraphic South Arabian script. The Ge'ez language is no longer universally thought of, as previously assumed, to be an offshoot of Sabaean or Old South Arabian,[18] and there is some linguistic (though not written) evidence of Semitic languages being spoken in Eritrea and Ethiopia since approximately 2000 BC.[19] However, the Ge'ez script later replaced Epigraphic South Arabian in the Kingdom of Aksum. Epigraphic South Arabian letters were used for a few inscriptions into the 8th century, though not any South Arabian language since Dʿmt. Early inscriptions in Ge'ez and Ge'ez script have been dated[20] to as early as the 5th century BC, and in a sort of proto-Ge'ez written in ESA since the 9th century BC. Ge'ez literature properly begins with the Christianization of Ethiopia (and the civilization of Axum) in the 4th century, during the reign of Ezana of Axum.[17]

5th to 7th centuries

The oldest known example of the old Ge'ez script is found on the Hawulti obelisk in Matara, Eritrea. The oldest surviving Ge'ez manuscript is thought to be the 5th or 6th century Garima Gospels.[21][22] Almost all texts from this early "Aksumite" period are religious (Christian) in nature, and translated from Greek. The Ethiopic Bible contains 81 Books: 46 of the Old Testament and 35 of the New. A number of these Books are called "deuterocanonical" (or "apocryphal" according to certain Western theologians), such as the Ascension of Isaiah, Jubilees, Enoch, the Paralipomena of Baruch, Noah, Ezra, Nehemiah, Maccabees, and Tobit. The Book of Enoch in particular is notable since its complete text has survived in no other language. Also to this early period dates Qerlos, a collection of Christological writings beginning with the treatise of Saint Cyril (known as Hamanot Rete’et or De Recta Fide). These works are the theological foundation of the Ethiopic Church. In the later 5th century, the Aksumite Collection—an extensive selection of liturgical, theological, synodical and historical materials—was translated into Ge'ez from Greek, providing a fundamental set of instructions and laws for the developing Ethiopian Church. Another important religious document is Ser'ata Paknemis, a translation of the monastic Rules of Pachomius. Non-religious works translated in this period include Physiologus, a work of natural history also very popular in Europe.[23]

13th to 14th centuries

After the decline of the Aksumites, a lengthy gap follows; no works have survived that can be dated to the years of the 8th through 12th centuries. Only with the rise of the Solomonic dynasty around 1270 can we find evidence of authors committing their works to writings. Some writers consider the period beginning from the 14th century an actual "Golden Age" of Ge'ez literature—although by this time Ge'ez was no longer a living language. While there is ample evidence that it had been replaced by Amharic in the south and by Tigrigna and Tigre in the north, Ge'ez remained in use as the official written language until the 19th century, its status comparable to that of Medieval Latin in Europe. Important hagiographies from this period include:

- the Gadle Sama’etat "Acts of the Martyrs"

- the Gadle Hawaryat "Acts of the Apostles"

- the Senkessar or Synaxarium, translated as "The Book of the Saints of the Ethiopian Church"

- Other Lives of Saint Anthony, Saint George, Saint Tekle Haymanot, Saint Gabra Manfas Qeddus

Also at this time the Apostolic Constitutions was retranslated into Ge'ez from Arabic. Another translation from this period is Zena 'Ayhud, a translation (probably from an Arabic translation) of Joseph ben Gurion's "History of the Jews" ("Sefer Josippon") written in Hebrew in the 10th century, which covers the period from the Captivity to the capture of Jerusalem by Titus. Apart from theological works, the earliest contemporary Royal Chronicles of Ethiopia are date to the reign of Amda Seyon I (1314–44). With the appearance of the "Victory Songs" of Amda Seyon, this period also marks the beginning of Amharic literature. The 14th century Kebra Nagast or "Glory of the Kings" by the Nebura’ed Yeshaq of Aksum is among the most significant works of Ethiopian literature, combining history, allegory and symbolism in a retelling of the story of the Queen of Sheba (i.e. Saba), King Solomon, and their son Menelik I of Ethiopia. Another work that began to take shape in this period is the Mashafa Aksum or "Book of Axum".[24]

15th to 16th centuries

The early 15th century Fekkare Iyasus "The Explication of Jesus" contains a prophecy of a king called Tewodros, which rose to importance in 19th century Ethiopia as Tewodros II chose this throne name. Literature flourished especially during the reign of Emperor Zara Yaqob. Written by the Emperor himself were Mats'hafe Berhan ("The Book of Light") and Matshafe Milad ("The Book of Nativity"). Numerous homilies were written in this period, notably Retu’a Haimanot ("True Orthodoxy") ascribed to John Chrysostom. Also of monumental importance was the appearance of the Ge'ez translation of the Fetha Negest ("Laws of the Kings"), thought to have been around 1450, and ascribed to one Petros Abda Sayd — that was later to function as the supreme Law for Ethiopia, until it was replaced by a modern Constitution in 1931.

By the beginning of the 16th century, the Islamic invasions put an end to the flourishing of Ethiopian literature. A letter of Abba 'Enbaqom (or "Habakkuk") to Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi, entitled Anqasa Amin ("Gate of the Faith"), giving his reasons for abandoning Islam, although probably first written in Arabic and later rewritten in an expanded Ge'ez version around 1532, is considered one of the classics of later Ge'ez literature.[25] During this period, Ethiopian writers begin to address differences between the Ethiopian and the Roman Catholic Church in such works as the Confession of Emperor Gelawdewos, Sawana Nafs ("Refuge of the Soul"), Fekkare Malakot ("Exposition of the Godhead") and Haymanote Abaw ("Faith of the Fathers"). Around the year 1600, a number of works were translated from Arabic into Ge'ez for the first time, including the Chronicle of John of Nikiu and the Universal History of George Elmacin.

Current usage in Eritrea, Ethiopia and Israel

Ge'ez is the liturgical language of Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo, Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo, Ethiopian Catholic and Eritrean Catholic Christians, and is used in prayer and in scheduled public celebrations. It is also used liturgically by the Beta Israel (Falasha Jews).

The liturgical rite used by the Christian churches is referred to as the Ethiopic Rite[26][27][28] or the Ge'ez Rite.[29][30][31][32]

Sample

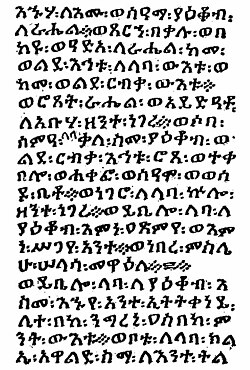

The first sentence of the Book of Enoch:

- ቃለ፡ በረከት፡ ዘሄኖክ፡ ዘከመ፡ ባረከ፡ ኅሩያነ፡ ወጻድቃነ፡ እለ፡ ሀለዉ፡ ይኩኑ፡

- በዕለተ፡ ምንዳቤ፡ ለአሰስሎ፡ ኵሉ፡ እኩያን፡ ወረሲዓን።

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.

- "Word of blessing of Henok, wherewith he blessed the chosen and righteous who would be alive in the day of tribulation for the removal of all wrongdoers and backsliders."

See also

- Ethiopian chant

Notes

- ↑ De Lacy O'Leary, 2000 Comparative grammar of the Semitic languages. Routledge. p. 23.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Gene Gragg 1997. The Semitic Languages. Taylor & Francis. Robert Hetzron ed. ISBN:978-0-415-05767-7.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "No longer in popular use, Ge'ez has always remained the language of the Church", [CHA]

- ↑ "They read the Bible in Geez" (Leaders and Religion of the Falashas); "after each passage, recited in Geez, the translation is read in Kailina" (Festivals). [PER]. Note the publication date of this source.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin, eds (2017). "Geez". Glottolog 3.0. Jena, Germany: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. http://glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/geez1241.

- ↑ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student's Handbook, Edinburgh

- ↑ Geez (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, September 2005, http://oed.com/search?searchType=dictionary&q=Geez (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Bulakh, Maria; Kogan, Leonid (2010). "The Genealogical Position of Tigre and the Problem of North Ethio-Semitic Unity". Zeitschriften der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 160 (2): 273–302.

- ↑ Demeke, Girma A. “The Ethio-Semitic Languages (Re-Examining the Classification).” Journal of Ethiopian Studies, vol. 34, no. 2, 2001, pp. 57–93. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/41966122

- ↑ Thompson, E. D. 1976. Languages of Northern Eritrea. In Bender, M. Lionel (ed.), The Non-Semitic Languages of Ethiopia, 597-603. East Lansing, Michigan: African Studies Center, Michigan State University.

- ↑ Connell, Dan; Killion, Tom (2010). Historical Dictionary of Eritrea (2nd, illustrated ed.). Scarecrow Press. p. 508. ISBN 978-0-8108-7505-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=SYsgpIc3mrsC&pg=PA508.

- ↑ Haarmann, Harald (2002) (in German). Lexikon der untergegangenen Sprachen (2nd ed.). C. H. Beck. p. 76. ISBN 978-3-406-47596-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=astTBgYBTOQC&pg=PA76.

- ↑ Amsalu Aklilu, Kuraz Publishing Agency, ጥሩ የአማርኛ ድርሰት እንዴት ያለ ነው! p. 42

- ↑ Lambdin, Thomas O. (1978).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Gene Gragg, 2008. "The Ancient Languages of Mesopotamia, Egypt and Aksum". Cambridge University Press. Roger D. Woodard Ed.

- ↑ [PAN], pp. 666f.; cf. the EOTC's own account at its official website. Church Teachings. Retrieved from the Internet Archive on March 12, 2014.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "Ethiopic Language in the International Standard Bible Encyclopedia." (in en). http://www.internationalstandardbible.com/E/ethiopic-language.html.

- ↑ Weninger, Stefan, "Ge'ez" in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha, p.732.

- ↑ Stuart, Munro-Hay (1991). Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: University Press. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-7486-0106-6.

- ↑ [MAT]

- ↑ A conservator at work on the Garima Gospels (2010-07-14). ""Discovery of earliest illustrated manuscript," Martin Bailey, June 2010". Theartnewspaper.com. http://www.theartnewspaper.com/…/Discovery-of-earlies…/20990. Retrieved 2012-07-11.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "The Arts Newspaper June 2010 – Abuna Garima Gospels". Ethiopianheritagefund.org. Archived from the original on 2012-05-01. https://web.archive.org/web/20120501030359/http://ethiopianheritagefund.org/artsNewspaper.html. Retrieved 2012-07-11.

- ↑ [BUD], pp. 566f.

- ↑ [BUD], p. 574

- ↑ [PAN03]

- ↑ Bryan D. Spinks, The Sanctus in the Eucharistic Prayer (Cambridge University Press 2002 ISBN:978-0-521-52662-3), p. 119

- ↑ Anscar J. Chupungco, Handbook for Liturgical Studies (Liturgical Press 1997 ISBN:978-0-8146-6161-1), p. 13

- ↑ Archdale King, The Rites of Eastern Christendom, vol. 1 (Gorgias Press LLC 2007 ISBN:978-1-59333-391-1), p. 533

- ↑ Paul B. Henze, Layers of Time: A History of Ethiopia (C. Hurst & Co. 2000 ISBN:978-1-85065-393-6), p. 127

- ↑ Erwin Fahlbusch, Geoffrey William Bromiley (editors), The Encyclopedia of Christianity, vol. 2 (Eerdmans 1999 ISBN:978-90-04-11695-5), p. 158

- ↑ David H. Shinn, Thomas P. Ofcansky (editors), Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia (Scarecrow Press 2013), p. 93

- ↑ Walter Raunig, Steffen Wenig (editors), Afrikas Horn (Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005, ISBN:978-3-447-05175-0), p. 171

References

- [BUD] Budge, E. A. Wallis. 1928. A History of Ethiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia, Oosterhout, the Netherlands: Anthropological Publications, 1970.

- CHA Chain, M. Ethiopia transcribed by: Donahue M. in The Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume V. Published 1909. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Nihil Obstat, May 1, 1909. Remy Lafort, Censor. Imprimatur. + John M. Farley, Archbishop of New York

- [DIR] Diringer, David. 1968. The Alphabet, A Key To The History of Mankind.

- [KOB] Kobishchanov, Yuri M. 1979. Axum, edited by Joseph W. Michels; translated by: Lorraine T. Kapitanoff. University Park, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania. ISBN:978-0-271-00531-7.

- MAT Matara Aksumite & Pre-Aksumite City Webpage

- MUN[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}] Munro-Hay Stuart. 1991. Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: University Press. ISBN:978-0-7486-0106-6.

- [PAN68] Pankhurst, Richard K.P. 1968.An Economic History of Ethiopia, 1800–1935, Addis Ababa: Haile Selassie I University Press.

- PAN03 Pankhurst, Richard K.P. A Glimpse into 16th. Century Ethiopian History Abba 'Enbaqom, Imam Ahmad Ibn Ibrahim, and the "Conquest of Abyssinia". Addis Tribune. November 14, 2003.

- PER[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}] Perruchon, J. D. and Gottheil, Richard. "Falashas" in The Jewish Encyclopedia. 1901–1906.

Further reading

Grammar

- Aläqa Tayyä, Maṣḥafa sawāsəw. Monkullo: Swedish Mission 1896/7 (= E.C. 1889).

- Chaîne, Marius, Grammaire éthiopienne. Beyrouth (Beirut): Imprimerie catholique 1907, 1938 (Nouvelle édition). (electronic version at the Internet Archive)

- Cohen, Marcel, "la pronunciation traditionelle du Guèze (éthiopien classique)", in: Journal asiatique (1921) Sér. 11 / T. 18 (electronic version in Gallica digital library of the Bibliothèque nationale de France PDF).

- Dillmann, August; Bezold, Carl, Ethiopic Grammar, 2nd edition translated from German by James Crichton, London 1907. ISBN:978-1-59244-145-7 (2003 reprint). (Published in German: ¹1857, ²1899). (Online version at the Internet Archive)

- Gäbrä-Yohannəs Gäbrä-Maryam, Gəss – Mäzgäbä-ḳalat – Gə'əz-ənna Amarəñña; yä-Gə'əz ḳʷanḳʷa mämmariya (A Grammar of Classical Ethiopic). Addis Ababa 2001/2002 (= E.C. 1994)[1][|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- Gene Gragg "Ge`ez Phonology," in: Phonologies of Asia and Africa (Vol 1), ed. A. S. Kaye & P. T. Daniels, Eisenbrauns, Winona Lake, Indiana (1997).

- Kidanä Wäld Kəfle, Maṣḥafa sawāsəw wagəss wamazgaba ḳālāt ḥaddis ("A new grammar and dictionary"), Dire Dawa: Artistik Matämiya Bet 1955/6 (E.C. 1948).

- Lambdin, Thomas O., Introduction to Classical Ethiopic, Harvard Semitic Studies 24, Missoula, Mont.: Scholars Press 1978. ISBN:978-0-89130-263-6.

- Mercer, Samuel Alfred Browne, "Ethiopic grammar: with chrestomathy and glossary" 1920 (Online version at the Internet Archive)

- Ludolf, Hiob, Grammatica aethiopica. Londini 1661; 2nd ed. Francofurti 1702.

- Praetorius, Franz, Äthiopische Grammatik, Karlsruhe: Reuther 1886.

- Prochazka, Stephan, Altäthiopische Studiengrammatik, Orbis Biblicus Et Orientalis – Subsidia Linguistica (OBO SL) 2, Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Verlag 2005. ISBN:978-3-525-26409-6.

- Qeleb, Desie (2010). The Revival of Geez. MPID 3948485819.

- Tropper, Josef, Altäthiopisch: Grammatik der Ge'ez mit Übungstexten und Glossar, Elementa Linguarum Orientis (ELO) 2, Münster: Ugarit-Verlag 2002. ISBN:978-3-934628-29-8

- Vittorio, Mariano, Chaldeae seu Aethiopicae linguae institutiones, Rome 1548.

- Weninger, Stefan, Ge‘ez grammar, Munich: LINCOM Europa, ISBN:978-3-929075-04-5 (1st edition, 1993), ISBN:978-3-89586-604-3 (2nd revised edition, 1999).

- Weninger, Stefan, Das Verbalsystem des Altäthiopischen: Eine Untersuchung seiner Verwendung und Funktion unter Berücksichtigung des Interferenzproblems", Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 2001. ISBN:978-3-447-04484-4.

- Wemmers, J., Linguae aethiopicae institutiones, Rome 1638.

• Zerezghi Haile, Learn Basic Geez Grammar (2015) for Tigrinya readers available at: https://uwontario.academia.edu/WedGdmhra

Literature

- Adera, Taddesse, Ali Jimale Ahmed (eds.), Silence Is Not Golden: A Critical Anthology of Ethiopian Literature, Red Sea Press (1995), ISBN:978-0-932415-47-9.

- Bonk, Jon, Annotated and Classified Bibliography of English Literature Pertaining to the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, Atla Bibliography Series, Scarecrow Pr (1984), ISBN:978-0-8108-1710-4.

- Charles, Robert Henry, The Ethiopic version of the book of Enoch. Oxford 1906. (Online version at the Internet Archive)

- Dillmann, August, Chrestomathia Aethiopica. Leipzig 1866. (Online version at the Internet Archive)

- Dillmann, August, Octateuchus Aethiopicus. Leipzig 1853. (The first eight books of the Bible in Ge'ez. Online version)

- Dillmann, August, Anthologia Aethiopica, Herausgegeben und mit einem Nachwort versehen von Ernst Hammerschmidt. Hildesheim: Olms Verlag 1988, ISBN:978-3-487-07943-1 .

- The Royal Chronicles of Zara Yaqob and Baeda Maryam – French translation and edition of the Ge'ez text Paris 1893 (electronic version[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}] in Gallica digital library of the Bibliothèque nationale de France)

- Ethiopic recension of the Chronicle of John of Nikiû – Paris 1883 (electronic version[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]) in Gallica

Dictionaries

- Dillmann, August, Lexicon linguæ Æthiopicæ cum indice Latino, Lipsiae 1865. (Online version at the Internet Archive)

- Leslau, Wolf, Comparative Dictionary of Geez (Classical Ethiopic): Geez-English, English-Geez, with an Index of the Semitic Roots, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 1987. ISBN:978-3-447-02592-8.

- Leslau, Wolf, Concise Dictionary of Ge‘ez (Classical Ethiopic), Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz 1989. ISBN:978-3-447-02873-8.

- Ludolf, Hiob, Lexicon Aethiopico-Latinum, Ed. by J. M. Wansleben, London 1661.

- Wemmers, J., Lexicon Aethiopicum, Rome 1638.

External links

- J. M.Harden, An Introduction to Ethiopic Christian Literature (1926)[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- Unicode Chart

- Researcher identifies second-oldest Ethiopian manuscript in existence in HMML's archives[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}], Walta Information Center (10 December 2010)

- LIBRARY OF ETHIOPIAN TEXTS