Finance:Greeks

In mathematical finance, the Greeks are the quantities (known in calculus as partial derivatives; first-order or higher) representing the sensitivity of the price of a derivative instrument such as an option to changes in one or more underlying parameters on which the value of an instrument or portfolio of financial instruments is dependent. The name is used because the most common of these sensitivities are denoted by Greek letters (as are some other finance measures). Collectively these have also been called the risk sensitivities,[1] risk measures[2]:742 or hedge parameters.[3]

Use of the Greeks

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Definition of Greeks as the sensitivity of an option's price and risk (in the first row) to the underlying parameter (in the first column). First-order Greeks are in blue, second-order Greeks are in green, and third-order Greeks are in yellow. Vanna, charm and veta appear twice, since partial cross derivatives are equal by Schwarz's theorem. Rho, lambda, epsilon, and vera are left out as they are not as important as the rest. Three places in the table are not occupied, because the respective quantities have not yet been defined in the financial literature. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Greeks are vital tools in risk management. Each Greek measures the sensitivity of the value of a portfolio to a small change in a given underlying parameter, so that component risks may be treated in isolation, and the portfolio rebalanced accordingly to achieve a desired exposure; see for example delta hedging.

The Greeks in the Black–Scholes model (a relatively simple idealised model of certain financial markets) are relatively easy to calculate — a desirable property of financial models — and are very useful for derivatives traders, especially those who seek to hedge their portfolios from adverse changes in market conditions. For this reason, those Greeks which are particularly useful for hedging—such as delta, theta, and vega—are well-defined for measuring changes in the parameters spot price, time and volatility. Although rho (the partial derivative with respect to the risk-free interest rate) is a primary input into the Black–Scholes model, the overall impact on the value of a short-term option corresponding to changes in the risk-free interest rate is generally insignificant and therefore higher-order derivatives involving the risk-free interest rate are not common.

The most common of the Greeks are the first order derivatives: delta, vega, theta and rho; as well as gamma, a second-order derivative of the value function. The remaining sensitivities in this list are common enough that they have common names, but this list is by no means exhaustive.

The players in the market make competitive trades involving many billions (of $, £ or €) of underlying every day, so it is important to get the sums right. In practice they will use more sophisticated models which go beyond the simplifying assumptions used in the Black-Scholes model and hence in the Greeks.

Names

The use of Greek letter names is presumably by extension from the common finance terms alpha and beta, and the use of sigma (the standard deviation of logarithmic returns) and tau (time to expiry) in the Black–Scholes option pricing model. Several names such as "vega" (whose symbol is similar to the lower-case Greek letter nu; the use of that name might have led to confusion) and "zomma" are invented, but sound similar to Greek letters. The names "color" and "charm" presumably derive from the use of these terms for exotic properties of quarks in particle physics.

First-order Greeks

Delta

Delta,[4] [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math], measures the rate of change of the theoretical option value with respect to changes in the underlying asset's price. Delta is the first derivative of the value [math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math] of the option with respect to the underlying instrument's price [math]\displaystyle{ S }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta = \frac{\partial V}{\partial S} }[/math]

Practical use

For a vanilla option, delta will be a number between 0.0 and 1.0 for a long call (or a short put) and 0.0 and −1.0 for a long put (or a short call); depending on price, a call option behaves as if one owns 1 share of the underlying stock (if deep in the money), or owns nothing (if far out of the money), or something in between, and conversely for a put option. The difference between the delta of a call and the delta of a put at the same strike is equal to one. By put–call parity, long a call and short a put is equivalent to a forward F, which is linear in the spot S, with unit factor, so the derivative dF/dS is 1. See the formulas below.

These numbers are commonly presented as a percentage of the total number of shares represented by the option contract(s). This is convenient because the option will (instantaneously) behave like the number of shares indicated by the delta. For example, if a portfolio of 100 American call options on XYZ each have a delta of 0.25 (= 25%), it will gain or lose value just like 2,500 shares of XYZ as the price changes for small price movements (100 option contracts covers 10,000 shares). The sign and percentage are often dropped – the sign is implicit in the option type (negative for put, positive for call) and the percentage is understood. The most commonly quoted are 25 delta put, 50 delta put/50 delta call, and 25 delta call. 50 Delta put and 50 Delta call are not quite identical, due to spot and forward differing by the discount factor, but they are often conflated.

Delta is always positive for long calls and negative for long puts (unless they are zero). The total delta of a complex portfolio of positions on the same underlying asset can be calculated by simply taking the sum of the deltas for each individual position – delta of a portfolio is linear in the constituents. Since the delta of underlying asset is always 1.0, the trader could delta-hedge his entire position in the underlying by buying or shorting the number of shares indicated by the total delta. For example, if the delta of a portfolio of options in XYZ (expressed as shares of the underlying) is +2.75, the trader would be able to delta-hedge the portfolio by selling short 2.75 shares of the underlying. This portfolio will then retain its total value regardless of which direction the price of XYZ moves. (Albeit for only small movements of the underlying, a short amount of time and not-withstanding changes in other market conditions such as volatility and the rate of return for a risk-free investment).

As a proxy for probability

The (absolute value of) Delta is close to, but not identical with, the percent moneyness of an option, i.e., the implied probability that the option will expire in-the-money (if the market moves under Brownian motion in the risk-neutral measure).[5] For this reason some option traders use the absolute value of delta as an approximation for percent moneyness. For example, if an out-of-the-money call option has a delta of 0.15, the trader might estimate that the option has approximately a 15% chance of expiring in-the-money. Similarly, if a put contract has a delta of −0.25, the trader might expect the option to have a 25% probability of expiring in-the-money. At-the-money calls and puts have a delta of approximately 0.5 and −0.5 respectively with a slight bias towards higher deltas for ATM calls since the risk-free rate introduces some offset to the delta. The actual probability of an option finishing in the money is its dual delta, which is the first derivative of option price with respect to strike.[6]

Relationship between call and put delta

Given a European call and put option for the same underlying, strike price and time to maturity, and with no dividend yield, the sum of the absolute values of the delta of each option will be 1 – more precisely, the delta of the call (positive) minus the delta of the put (negative) equals 1. This is due to put–call parity: a long call plus a short put (a call minus a put) replicates a forward, which has delta equal to 1.

If the value of delta for an option is known, one can calculate the value of the delta of the option of the same strike price, underlying and maturity but opposite right by subtracting 1 from a known call delta or adding 1 to a known put delta.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta(\text{call}) - \Delta(\text{put}) = 1, \text{ therefore: } \Delta(\text{call}) = \Delta(\text{put}) + 1 \text{ and } \Delta(\text{put}) = \Delta(\text{call}) - 1. }[/math]

For example, if the delta of a call is 0.42 then one can compute the delta of the corresponding put at the same strike price by 0.42 − 1 = −0.58. To derive the delta of a call from a put, one can similarly take −0.58 and add 1 to get 0.42.

Vega

Vega[4] measures sensitivity to volatility. Vega is the derivative of the option value with respect to the volatility of the underlying asset.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{V}=\frac{\partial V}{\partial \sigma} }[/math]

Vega is not the name of any Greek letter. The glyph used is a non-standard majuscule version of the Greek letter nu ([math]\displaystyle{ \nu }[/math]), written as [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{V} }[/math]. Presumably the name vega was adopted because the Greek letter nu looked like a Latin vee, and vega was derived from vee by analogy with how beta, eta, and theta are pronounced in American English.

The symbol kappa, [math]\displaystyle{ \kappa }[/math], is sometimes used (by academics) instead of vega (as is tau ([math]\displaystyle{ \tau }[/math]) or capital lambda ([math]\displaystyle{ \Lambda }[/math]),[7] :315 though these are rare).

Vega is typically expressed as the amount of money per underlying share that the option's value will gain or lose as volatility rises or falls by 1 percentage point. All options (both calls and puts) will gain value with rising volatility.

Vega can be an important Greek to monitor for an option trader, especially in volatile markets, since the value of some option strategies can be particularly sensitive to changes in volatility. The value of an at-the-money option straddle, for example, is extremely dependent on changes to volatility.

Theta

Theta,[4] [math]\displaystyle{ \Theta }[/math], measures the sensitivity of the value of the derivative to the passage of time (see Option time value): the "time decay."

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Theta = -\frac{\partial V}{\partial \tau} }[/math]

As time passes, with decreasing time to expiry and all else being equal, an option's extrinsic value decreases. Typically (but see below), this means an option loses value with time, which is conventionally referred to as long options typically having short (negative) theta. In fact, typically, the literal first derivative w.r.t. time of an option's value is a positive number. The change in option value is typically negative because the passage of time is a negative number (a decrease to [math]\displaystyle{ r \, }[/math], time to expiry). However, by convention, practitioners usually prefer to refer to theta exposure ("decay") of a long option as negative (instead of the passage of time as negative), and so theta is usually reported as -1 times the first derivative, as above.

While extrinsic value is decreasing with time passing, sometimes a countervailing factor is discounting. For deep-in-the-money options of some types (for puts in Black-Scholes, puts and calls in Black's), as discount factors increase towards 1 with the passage of time, that is an element of increasing value in a long option. Sometimes deep-in-the-money options will gain more from increasing discount factors than they lose from decreasing extrinsic value, and reported theta will be a positive value for a long option instead of a more typical negative value (and the option will be an early exercise candidate, if exercisable, and a European option may become worth less than parity).

By convention in options valuation formulas, [math]\displaystyle{ r \, }[/math], time to expiry, is defined in years. Practitioners commonly prefer to view theta in terms of change in number of days to expiry rather than number of years to expiry. Therefore, reported theta is usually divided by number of days in a year. (Whether to count calendar days or business days varies by personal choice, with arguments for both.)

Rho

Rho,[4] [math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math], measures sensitivity to the interest rate: it is the derivative of the option value with respect to the risk-free interest rate (for the relevant outstanding term).

- [math]\displaystyle{ \rho = \frac{\partial V}{\partial r} }[/math]

Except under extreme circumstances, the value of an option is less sensitive to changes in the risk-free interest rate than to changes in other parameters. For this reason, rho is the least used of the first-order Greeks.

Rho is typically expressed as the amount of money, per share of the underlying, that the value of the option will gain or lose as the risk-free interest rate rises or falls by 1.0% per annum (100 basis points).

Lambda

Lambda,[4] [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math], omega,[8] [math]\displaystyle{ \Omega }[/math], or elasticity[4] is the percentage change in option value per percentage change in the underlying price, a measure of leverage, sometimes called gearing.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda = \Omega = \frac{\partial V}{\partial S}\times\frac{S}{V} }[/math]

It holds that [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda = \Omega = \Delta\times\frac{S}{V} }[/math].

It is similar to the concept of delta but expressed in percentage terms rather than absolute terms.

Epsilon

Epsilon,[9] [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon }[/math] (also known as psi, [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math]), is the percentage change in option value per percentage change in the underlying dividend yield, a measure of the dividend risk. The dividend yield impact is in practice determined using a 10% increase in those yields. Obviously, this sensitivity can only be applied to derivative instruments of equity products.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varepsilon = \psi = \frac{\partial V}{\partial q} }[/math]

Numerically, all first-order sensitivities can be interpreted as spreads in expected returns.[10] Information geometry offers another (trigonometric) interpretation.[10]

Second-order Greeks

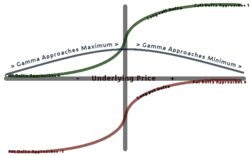

Gamma

Gamma,[4] [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma }[/math], measures the rate of change in the delta with respect to changes in the underlying price. Gamma is the second derivative of the value function with respect to the underlying price.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma = \frac{\partial \Delta}{\partial S} = \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial S^2} }[/math]

Most long options have positive gamma and most short options have negative gamma. Long options have a positive relationship with gamma because as price increases, Gamma increases as well, causing Delta to approach 1 from 0 (long call option) and 0 from −1 (long put option). The inverse is true for short options.[11]

Gamma is greatest approximately at-the-money (ATM) and diminishes the further out you go either in-the-money (ITM) or out-of-the-money (OTM). Gamma is important because it corrects for the convexity of value.

When a trader seeks to establish an effective delta-hedge for a portfolio, the trader may also seek to neutralize the portfolio's gamma, as this will ensure that the hedge will be effective over a wider range of underlying price movements.

Vanna

Vanna,[4] also referred to as DvegaDspot[13] and DdeltaDvol,[13] is a second-order derivative of the option value, once to the underlying spot price and once to volatility. It is mathematically equivalent to DdeltaDvol, the sensitivity of the option delta with respect to change in volatility; or alternatively, the partial of vega with respect to the underlying instrument's price. Vanna can be a useful sensitivity to monitor when maintaining a delta- or vega-hedged portfolio as vanna will help the trader to anticipate changes to the effectiveness of a delta-hedge as volatility changes or the effectiveness of a vega-hedge against change in the underlying spot price.

If the underlying value has continuous second partial derivatives, then [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Vanna} = \frac{\partial \Delta}{\partial \sigma} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{V}}{\partial S} = \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial S \, \partial \sigma}. }[/math]

Charm

Charm[4] or delta decay[14] measures the instantaneous rate of change of delta over the passage of time.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Charm} = -\frac{\partial \Delta}{\partial \tau} = \frac{\partial \Theta}{\partial S} = -\frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial \tau \, \partial S} }[/math]

Charm has also been called DdeltaDtime.[13] Charm can be an important Greek to measure/monitor when delta-hedging a position over a weekend. Charm is a second-order derivative of the option value, once to price and once to the passage of time. It is also then the derivative of theta with respect to the underlying's price.

The mathematical result of the formula for charm (see below) is expressed in delta/year. It is often useful to divide this by the number of days per year to arrive at the delta decay per day. This use is fairly accurate when the number of days remaining until option expiration is large. When an option nears expiration, charm itself may change quickly, rendering full day estimates of delta decay inaccurate.

Vomma

Vomma,[4] volga,[15] vega convexity,[15] or DvegaDvol[15] measures second-order sensitivity to volatility. Vomma is the second derivative of the option value with respect to the volatility, or, stated another way, vomma measures the rate of change to vega as volatility changes.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Vomma} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{V}}{\partial \sigma} = \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial \sigma^2} }[/math]

With positive vomma, a position will become long vega as implied volatility increases and short vega as it decreases, which can be scalped in a way analogous to long gamma. And an initially vega-neutral, long-vomma position can be constructed from ratios of options at different strikes. Vomma is positive for long options away from the money, and initially increases with distance from the money (but drops off as vega drops off). (Specifically, vomma is positive where the usual d1 and d2 terms are of the same sign, which is true when d1 < 0 or d2 > 0.)

Veta

Veta[16] or DvegaDtime[15] measures the rate of change in the vega with respect to the passage of time. Veta is the second derivative of the value function; once to volatility and once to time.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Veta} = \frac{\partial \mathcal{V}}{\partial \tau} = \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial \sigma \, \partial \tau} }[/math]

It is common practice to divide the mathematical result of veta by 100 times the number of days per year to reduce the value to the percentage change in vega per one day.

Vera

Vera[17] (sometimes rhova)[17] measures the rate of change in rho with respect to volatility. Vera is the second derivative of the value function; once to volatility and once to interest rate.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Vera} = \frac{\partial \rho}{\partial \sigma} = \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial \sigma \, \partial r} }[/math]

The word 'Vera' was coined by R. Naryshkin in early 2012 when this sensitivity needed to be used in practice to assess the impact of volatility changes on rho-hedging, but no name yet existed in the available literature. 'Vera' was picked to sound similar to a combination of Vega and Rho, its respective first-order Greeks. This name is now in a wider use, including, for example, the Maple computer algebra software (which has 'BlackScholesVera' function in its Finance package).

Second-order partial derivative with respect to strike K

This partial derivative has a fundamental role in the Breeden–Litzenberger formula,[18] which uses quoted call option prices to estimate the risk-neutral probabilities implied by such prices.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi =\frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial K^2} }[/math]

For call options, it can be approximated using infinitesimal portfolios of butterfly strategies.

Third-order Greeks

Speed

Speed[4] measures the rate of change in Gamma with respect to changes in the underlying price.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Speed} = \frac{\partial\Gamma}{\partial S} = \frac{\partial^3 V}{\partial S^3} }[/math]

This is also sometimes referred to as the gamma of the gamma[2]:799 or DgammaDspot.[13] Speed is the third derivative of the value function with respect to the underlying spot price. Speed can be important to monitor when delta-hedging or gamma-hedging a portfolio.

Zomma

Zomma[4] measures the rate of change of gamma with respect to changes in volatility.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Zomma} = \frac{\partial \Gamma}{\partial \sigma} = \frac{\partial \text{vanna}}{\partial S} = \frac{\partial^3 V}{\partial S^2 \, \partial \sigma} }[/math]

Zomma has also been referred to as DgammaDvol.[13] Zomma is the third derivative of the option value, twice to underlying asset price and once to volatility. Zomma can be a useful sensitivity to monitor when maintaining a gamma-hedged portfolio as zomma will help the trader to anticipate changes to the effectiveness of the hedge as volatility changes.

Color

Color,[13] gamma decay[19] or DgammaDtime[13] measures the rate of change of gamma over the passage of time.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Color} = \frac{\partial \Gamma}{\partial \tau} = \frac{\partial^3 V}{\partial S^2 \, \partial \tau} }[/math]

Color is a third-order derivative of the option value, twice to underlying asset price and once to time. Color can be an important sensitivity to monitor when maintaining a gamma-hedged portfolio as it can help the trader to anticipate the effectiveness of the hedge as time passes.

The mathematical result of the formula for color (see below) is expressed in gamma per year. It is often useful to divide this by the number of days per year to arrive at the change in gamma per day. This use is fairly accurate when the number of days remaining until option expiration is large. When an option nears expiration, color itself may change quickly, rendering full day estimates of gamma change inaccurate.

Ultima

Ultima[4] measures the sensitivity of the option vomma with respect to change in volatility.

- [math]\displaystyle{ \text{Ultima}= \frac{\partial \text{vomma}}{\partial \sigma} = \frac{\partial^3 V}{\partial \sigma^3} }[/math]

Ultima has also been referred to as DvommaDvol.[4] Ultima is a third-order derivative of the option value to volatility.

Greeks for multi-asset options

If the value of a derivative is dependent on two or more underlyings, its Greeks are extended to include the cross-effects between the underlyings.

Correlation delta measures the sensitivity of the derivative's value to a change in the correlation between the underlyings.[20] It is also commonly known as cega.[21][22]

Cross gamma measures the rate of change of delta in one underlying to a change in the level of another underlying.[23]

Cross vanna measures the rate of change of vega in one underlying due to a change in the level of another underlying. Equivalently, it measures the rate of change of delta in the second underlying due to a change in the volatility of the first underlying.[20]

Cross volga measures the rate of change of vega in one underlying to a change in the volatility of another underlying.[23]

Formulae for European option Greeks

The Greeks of European options (calls and puts) under the Black–Scholes model are calculated as follows, where [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi }[/math] (phi) is the standard normal probability density function and [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi }[/math] is the standard normal cumulative distribution function. Note that the gamma and vega formulas are the same for calls and puts.

For a given:

- Stock price [math]\displaystyle{ S \, }[/math],

- Strike price [math]\displaystyle{ K \, }[/math],

- Risk-free rate [math]\displaystyle{ r \, }[/math],

- Annual dividend yield [math]\displaystyle{ q \, }[/math],

- Time to maturity [math]\displaystyle{ \tau = T - t \, }[/math] (represented as a unit-less fraction of one year), and

- Volatility [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma \, }[/math].

| Calls | Puts | |

|---|---|---|

| fair value ([math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ Se^{-q \tau}\Phi(d_1) - e^{-r \tau} K\Phi(d_2) \, }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-r \tau} K\Phi(-d_2) - Se^{-q \tau}\Phi(-d_1) \, }[/math] |

| delta ([math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-q \tau} \Phi(d_1) \, }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -e^{-q \tau} \Phi(-d_1)\, }[/math] |

| vega ([math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{V} }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ S e^{-q \tau} \varphi(d_1) \sqrt{\tau} = K e^{-r \tau} \varphi(d_2) \sqrt{\tau} \, }[/math] | |

| theta ([math]\displaystyle{ \Theta }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ - e^{-q \tau} \frac{S \varphi(d_1) \sigma}{2 \sqrt{\tau}} - rKe^{-r \tau}\Phi(d_2) + qSe^{-q \tau}\Phi(d_1) \, }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ - e^{-q \tau}\frac{S \varphi(d_1) \sigma}{2 \sqrt{\tau}} + rKe^{-r \tau}\Phi(-d_2) - qSe^{-q \tau}\Phi(-d_1)\, }[/math] |

| rho ([math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ K \tau e^{-r \tau}\Phi(d_2)\, }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -K \tau e^{-r \tau}\Phi(-d_2) \, }[/math] |

| epsilon ([math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ -S \tau e^{-q \tau} \Phi(d_1) }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ S \tau e^{-q \tau} \Phi(-d_1) }[/math] |

| lambda ([math]\displaystyle{ \lambda }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ \Delta \frac{S}{V} \, }[/math] | |

| gamma ([math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-q \tau} \frac{\varphi(d_1)}{S\sigma\sqrt{\tau}} = K e^{-r \tau} \frac{\varphi(d_2)}{S^2\sigma\sqrt{\tau}} \, }[/math] | |

| vanna | [math]\displaystyle{ -e^{-q \tau} \varphi(d_1) \frac{d_2}{\sigma} \, = \frac{\mathcal{V}}{S}\left[1 - \frac{d_1}{\sigma\sqrt{\tau}} \right]\, }[/math] | |

| charm | [math]\displaystyle{ qe^{-q \tau} \Phi(d_1) - e^{-q \tau} \varphi(d_1) \frac{2(r-q) \tau - d_2 \sigma \sqrt{\tau}}{2\tau \sigma \sqrt{\tau}} \, }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -qe^{-q \tau} \Phi(-d_1) - e^{-q \tau} \varphi(d_1) \frac{2(r-q) \tau - d_2 \sigma \sqrt{\tau}}{2\tau \sigma \sqrt{\tau}} \, }[/math] |

| vomma | [math]\displaystyle{ Se^{-q \tau} \varphi(d_1) \sqrt{\tau} \frac{d_1 d_2}{\sigma} = \mathcal{V} \frac{d_1 d_2}{\sigma} \, }[/math] | |

| vera | [math]\displaystyle{ -K \tau e^{-r \tau} \varphi(d_2) \frac{d_1 }{\sigma} \, }[/math] | |

| veta | [math]\displaystyle{ -Se^{-q \tau} \varphi(d_1) \sqrt{\tau} \left[ q + \frac{ \left( r - q \right) d_1 }{ \sigma \sqrt{\tau} } - \frac{1 + d_1 d_2}{2 \tau} \right] \, }[/math] | |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \varphi }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-r\tau}\frac{1}{K}\frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2\tau}}\exp\left\{-\frac{1}{2\sigma^2\tau}\left[\ln\left(\frac{K}{S}\right)-\left((r-q)-\frac{1}{2}\sigma^2\right)\tau\right]^2\right\} }[/math] | |

| speed | [math]\displaystyle{ -e^{-q \tau} \frac{\varphi(d_1)}{S^2 \sigma \sqrt{\tau}} \left(\frac{d_1}{\sigma \sqrt{\tau}} + 1\right) = -\frac{\Gamma}{S}\left(\frac{d_1}{\sigma\sqrt{\tau}}+1\right) \, }[/math] | |

| zomma | [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-q \tau} \frac{\varphi(d_1)\left(d_1 d_2 - 1\right)}{S\sigma^2\sqrt{\tau}} = \Gamma\frac{d_1 d_2 -1}{\sigma} \, }[/math] | |

| color | [math]\displaystyle{ -e^{-q \tau} \frac{\varphi(d_1)}{2S\tau \sigma \sqrt{\tau}} \left[2q\tau + 1 + \frac{2(r-q) \tau - d_2 \sigma \sqrt{\tau}}{\sigma \sqrt{\tau}}d_1 \right] \, }[/math] | |

| ultima | [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{-\mathcal{V}}{\sigma^2} \left[ d_1 d_2 (1 - d_1 d_2) + d_1^2 + d_2^2 \right] }[/math] | |

| dual delta | [math]\displaystyle{ -e^{-r \tau} \Phi(d_2) \, }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-r \tau} \Phi(-d_2) \, }[/math] |

| dual gamma | [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-r \tau} \frac{\varphi(d_2)}{K\sigma\sqrt{\tau}} \, }[/math] | |

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} d_1 &= \frac{\ln(S/K) + \left(r - q + \frac{1}{2}\sigma^2\right)\tau}{\sigma\sqrt{\tau}} \\ d_2 &= \frac{\ln(S/K) + \left(r - q - \frac{1}{2}\sigma^2\right)\tau}{\sigma\sqrt{\tau}} = d_1 - \sigma\sqrt{\tau} \\ \varphi(x) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} e^{-\frac{1}{2} x^2} \\ \Phi(x) &= \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_{-\infty}^x e^{-\frac{1}{2} y^2} \,dy = 1 - \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi}} \int_x^\infty e^{-\frac{1}{2} y^2} \,dy \end{align} }[/math]

Under the Black model (commonly used for commodities and options on futures) the Greeks can be calculated as follows:

| Calls | Puts | |

|---|---|---|

| fair value ([math]\displaystyle{ V }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-r \tau}[F\Phi(d_1) - K\Phi(d_2)] \ }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-r \tau} [K\Phi(-d_2) - F\Phi(-d_1)] \, }[/math] |

| delta ([math]\displaystyle{ \Delta }[/math]) [math]\displaystyle{ =\partial V/\partial F }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-r \tau} \Phi(d_1) \, }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -e^{-r \tau} \Phi(-d_1)\, }[/math] |

| vega ([math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{V} }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ F e^{-r \tau} \varphi(d_1) \sqrt{\tau} = K e^{-r \tau} \varphi(d_2) \sqrt{\tau} \, }[/math] (*) | |

| theta ([math]\displaystyle{ \Theta }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ - \frac{F e^{-r \tau} \varphi(d_1) \sigma}{2 \sqrt{\tau}} - rKe^{-r \tau}\Phi(d_2) + rFe^{-r \tau}\Phi(d_1) \, }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ - \frac{F e^{-r \tau} \varphi(d_1) \sigma}{2 \sqrt{\tau}} + rKe^{-r \tau}\Phi(-d_2) - rFe^{-r \tau}\Phi(-d_1)\, }[/math] |

| rho ([math]\displaystyle{ \rho }[/math]) | [math]\displaystyle{ -\tau e^{-r \tau}[F\Phi(d_1) - K\Phi(d_2)] \ }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -\tau e^{-r \tau} [K\Phi(-d_2) - F\Phi(-d_1)] \, }[/math] |

| gamma ([math]\displaystyle{ \Gamma }[/math]) [math]\displaystyle{ = {\partial^2 V \over \partial F^2} }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ e^{-r \tau} \frac{\varphi(d_1)}{F\sigma\sqrt{\tau}} = K e^{-r \tau} \frac{\varphi(d_2)}{F^2\sigma\sqrt{\tau}} \, }[/math] (*) | |

| vanna [math]\displaystyle{ = \frac{\partial^2 V}{\partial F \partial \sigma} }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ -e^{-r \tau} \varphi(d_1) \frac{d_2}{\sigma} \, = \frac{\mathcal{V}}{F}\left[1 - \frac{d_1}{\sigma\sqrt{\tau}} \right]\, }[/math] | |

| vomma | [math]\displaystyle{ F e^{-r \tau} \varphi(d_1) \sqrt{\tau} \frac{d_1 d_2}{\sigma} = \mathcal{V} \frac{d_1 d_2}{\sigma} \, }[/math] | |

where

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{align} d_1 &= \frac{\ln(F/K) + \frac{1}{2}\sigma^2\tau}{\sigma\sqrt\tau} \\ d_2 &= \frac{\ln(F/K) - \frac{1}{2}\sigma^2\tau}{\sigma\sqrt\tau} = d_1 - \sigma\sqrt\tau \end{align} }[/math]

(*) It can be shown that [math]\displaystyle{ F\varphi(d_1) = K\varphi(d_2) }[/math]

Micro proof:

let [math]\displaystyle{ x= \sigma \sqrt \tau }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ d_1 = \frac{\ln \frac F K + \frac 1 2 x^2}{x} }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ d_1\cdot x = \ln \frac F K + \frac 1 2 x^2 }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \ln(F/K) = d_1\cdot x - \frac{1}{2}x^2 }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \frac{F}{K} = e^{d_1 \cdot x - \frac{1}{2}x^2} }[/math]

Then we have: [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{F}{K} \cdot \frac{\varphi(d_1)}{\varphi(d_2)} = \frac{F}{K} \cdot e^{\frac{1}{2}\cdot {d_2}^2 - \frac{1}{2}\cdot{d_1}^2} }[/math]

- [math]\displaystyle{ =e^{d_1 x - \frac{1}{2}x^2} \cdot e^{\frac{1}{2}\cdot{(d_1-x)}^2 - \frac{1}{2}\cdot{d_1}^2} = e^{d_1 x - \frac{1}{2}x^2 + \frac{1}{2} \cdot (2d_1 - x)(-x)} = e^0 = 1. }[/math]

So [math]\displaystyle{ F\varphi(d_1) = K\varphi(d_2) }[/math]

Related measures

Some related risk measures of financial instruments are listed below.

Bond duration and convexity

In trading bonds and other fixed income securities, various measures of bond duration are used analogously to the delta of an option. The closest analogue to the delta is DV01, which is the reduction in price (in currency units) for an increase of one basis point (i.e. 0.01% per annum) in the yield (the yield is the underlying variable). See also Bond duration § Risk – duration as interest rate sensitivity.

Analogous to the lambda is the modified duration, which is the percentage change in the market price of the bond(s) for a unit change in the yield (i.e. it is equivalent to DV01 divided by the market price). Unlike the lambda, which is an elasticity (a percentage change in output for a percentage change in input), the modified duration is instead a semi-elasticity—a percentage change in output for a unit change in input. See also Key rate duration.

Bond convexity is a measure of the sensitivity of the duration to changes in interest rates, the second derivative of the price of the bond with respect to interest rates (duration is the first derivative); it is then analogous to gamma. In general, the higher the convexity, the more sensitive the bond price is to the change in interest rates. Bond convexity is one of the most basic and widely used forms of convexity in finance.

For a bond with an embedded option, the standard yield to maturity based calculations here do not consider how changes in interest rates will alter the cash flows due to option exercise. To address this, effective duration and effective convexity are introduced. These values are typically calculated using a tree-based model, built for the entire yield curve (as opposed to a single yield to maturity), and therefore capturing exercise behavior at each point in the option's life as a function of both time and interest rates; see Lattice model (finance) § Interest rate derivatives.

Beta

The beta (β) of a stock or portfolio is a number describing the volatility of an asset in relation to the volatility of the benchmark that said asset is being compared to. This benchmark is generally the overall financial market and is often estimated via the use of representative indices, such as the S&P 500.

An asset has a Beta of zero if its returns change independently of changes in the market's returns. A positive beta means that the asset's returns generally follow the market's returns, in the sense that they both tend to be above their respective averages together, or both tend to be below their respective averages together. A negative beta means that the asset's returns generally move opposite the market's returns: one will tend to be above its average when the other is below its average.

Fugit

The fugit is the expected time to exercise an American or Bermudan option. Fugit is usefully computed for hedging purposes — for example, one can represent flows of an American swaption like the flows of a swap starting at the fugit multiplied by delta, and then use these to compute other sensitivities.

See also

- Alpha

- Beta

- Delta neutral

- Financial risk management

- Greek letters used in mathematics, science, and engineering

- PnL explained § Sensitivities method

- Vanna–Volga pricing

References

- ↑ Banks, Erik; Siegel, Paul (2006). The options applications handbook: hedging and speculating techniques for professional investors. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 263. ISBN 9780071453158.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Macmillan, Lawrence G. (1993). Options as a Strategic Investment (3rd ed.). New York Institute of Finance. ISBN 978-0-13-636002-5. https://archive.org/details/optionsasstrateg00mcmi.

- ↑ Chriss, Neil (1996). Black–Scholes and beyond: option pricing models. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 308. ISBN 9780786310258. https://archive.org/details/blackscholesbeyo00chri_0/page/308.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 Haug, Espen Gaardner (2007). The Complete Guide to Option Pricing Formulas. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 9780071389976.

- ↑ Suma, John. "Options Greeks: Delta Risk and Reward". http://www.investopedia.com/university/option-greeks/greeks2.asp.

- ↑ Steiner, Bob (2013). Mastering Financial Calculations (3rd ed.). Pearson UK. ISBN 9780273750604.

- ↑ Hull, John C. (1993). Options, Futures, and Other Derivative Securities (2nd ed.). Prentice-Hall. ISBN 9780136390145. https://archive.org/details/optionsfuturesot00hull_0.

- ↑ Omega – Investopedia

- ↑ De Spiegeleer, Jan; Schoutens, Wim (2015). The Handbook of Convertible Bonds: Pricing, Strategies and Risk Management. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 255, 269–270. ISBN 9780470689684.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Soklakov, A. N. (2023). "Information Geometry of Risks and Returns". Risk June.

- ↑ Willette, Jeff (2014-05-28). "Understanding How Gamma Affect Delta". http://www.traderbrains.com/the-greeks-understanding-how-gamma-affects-delta/.

- ↑ Willette, Jeff (2014-05-28). "Why is Long Option Gamma Positive". http://www.traderbrains.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/why-is-long-option-gamma-positive.png.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 Haug, Espen Gaarder (2003), "Know Your Weapon, Part 1", Wilmott Magazine (May 2003): 49–57, doi:10.1002/wilm.42820030313, http://www.espenhaug.com/KnowYourWeapon.pdf

- ↑ Derivatives – Delta Decay – The Financial Encyclopedia

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Haug, Espen Gaarder (2003), "Know Your Weapon, Part 2", Wilmott Magazine (July 2003): 43–57, https://www.scribd.com/document/26254888/Know-Your-Weapon-2

- ↑ Pierino Ursone. How to Calculate Options Prices and Their Greeks: Exploring the Black Scholes Model from Delta to Vega. John Wiley & Sons. 2015.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Derivatives – Second-Order Greeks – The Financial Encyclopedia

- ↑ Breeden, Litzenberger, Prices of State-Contingent Claims Implicit in Option Prices [1]

- ↑ "Derivatives – Greeks". Investment & Finance. http://www.investment-and-finance.net/derivatives/g/greeks.html. Retrieved 2020-12-21.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Greeks for Multi-Asset Options". http://www.investment-and-finance.net/derivatives/tutorials/greeks-for-multi-asset-options.html.

- ↑ Correlation Risk. http://sp-finance.e-monsite.com/pages/correlation/correlation-risk/correlation-risk.html. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ↑ "Rotating Mountain Range Options, Valuation & risks / Performance analysis". http://www.next-finance.net/Rotating-Mountain-Range-Options,516.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Fengler, Matthias; Schwendner, Peter (2003). Correlation Risk Premia for Multi-Asset Equity Options. Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche Fakultät. doi:10.18452/3572. http://edoc.hu-berlin.de/series/sfb-373-papers/2003-10/PDF/10.pdf.

External links

Theory

- Delta, Gamma, GammaP, Gamma symmetry, Vanna, Speed, Charm, Saddle Gamma: Vanilla Options - Espen Haug,

- Volga, Vanna, Speed, Charm, Color: Vanilla Options - Uwe Wystup, Vanilla Options - Uwe Wystup

Step-by-step mathematical derivations of option Greeks

- Derivation of European Vanilla Call Price

- Derivation of European Vanilla Call Delta

- Derivation of European Vanilla Call Gamma

- Derivation of European Vanilla Call Speed

- Derivation of European Vanilla Call Vega

- Derivation of European Vanilla Call Volga

- Derivation of European Vanilla Call Vanna as Derivative of Vega with respect to underlying

- Derivation of European Vanilla Call Vanna as Derivative of Delta with respect to volatility

- Derivation of European Vanilla Call Theta

- Derivation of European Vanilla Call Rho

- Derivation of European Vanilla Put Price

- Derivation of European Vanilla Put Delta

- Derivation of European Vanilla Put Gamma

- Derivation of European Vanilla Put Speed

- Derivation of European Vanilla Put Vega

- Derivation of European Vanilla Put Volga

- Derivation of European Vanilla Put Vanna as Derivative of Vega with respect to underlying

- Derivation of European Vanilla Put Vanna as Derivative of Delta with respect to volatility

- Derivation of European Vanilla Put Theta

- Derivation of European Vanilla Put Rho

Online tools

- Surface Plots of Black–Scholes Greeks, Chris Murray

- Online real-time option prices and Greeks calculator when the underlying is normally distributed, Razvan Pascalau, Univ. of Alabama

- greeks: Sensitivities of Prices of Financial Options, R package to compute Greeks for European-, American- and Asian options