Finance:Credit card interest

{{Sidebar with collapsible lists

| name = Finance sidebar

| title = Finance

| image =  | listtitlestyle = background:#ddf;text-align:center;

| listclass = plainlist

| expanded =

| listtitlestyle = background:#ddf;text-align:center;

| listclass = plainlist

| expanded =

| list1name = markets | list1title = Markets | list1 =

| Assets |

|---|

| Participants |

| Locations |

| list2name = instruments | list2title = Instruments | list2style = padding-left:2.0em;padding-right:2.0em;

| list2 =

Credit card interest is a way in which credit card issuers generate revenue. A card issuer is a bank or credit union that gives a consumer (the cardholder) a card or account number that can be used with various payees to make payments and borrow money from the bank simultaneously. The bank pays the payee and then charges the cardholder interest over the time the money remains borrowed. Banks suffer losses when cardholders do not pay back the borrowed money as agreed. As a result, optimal calculation of interest based on any information they have about the cardholder's credit risk is key to a card issuer's profitability. Before determining what interest rate to offer, banks typically check national, and international (if applicable), credit bureau reports to identify the borrowing history of the card holder applicant with other banks and conduct detailed interviews and documentation of the applicant's finances.

Interest rates

Interest rates vary widely. Some credit card loans are secured by real estate, and can be as low as 6 to 12% in the U.S. (2005).[citation needed] Typical credit cards have interest rates between 7 and 36% in the U.S., depending largely upon the bank's risk evaluation methods and the borrower's credit history. Brazil has much higher interest rates, about 50% over that of most developing countries, which average about 200% (Economist, May 2006). A Brazilian bank-issued Visa or MasterCard to a new account holder can have annual interest as high as 240% even though inflation seems to have gone up per annum (Economist, May 2006). Banco do Brasil offered its new checking account holders Visa and MasterCard credit accounts for 192% annual interest, with somewhat lower interest rates reserved for people with dependable income and assets (July 2005).[citation needed] These high-interest accounts typically offer very low credit limits (US$40 to $400). They also often offer a grace period with no interest until the due date, which makes them more popular for use as liquidity accounts, which means that the majority of consumers use them only for convenience to make purchases within the monthly budget, and then (usually) pay them off in full each month. As of August 2016, Brazilian rates can get as high as 450% per year.

Calculation of interest rates

Most U.S. credit cards are quoted in terms of nominal annual percentage rate (APR) compounded daily, or sometimes (and especially formerly) monthly, which in either case is not the same as the effective annual rate (EAR). Despite the "annual" in APR, it is not necessarily a direct reference for the interest rate paid on a stable balance over one year.

The more direct reference for the one-year rate of interest is EAR. The general conversion factor for APR to EAR is [math]\displaystyle{ EAR=(1+{APR \over n})^n-1 }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] represents the number of compounding periods of the APR per EAR period.

For a common credit card quoted at 12.99% APR compounded daily, the one-year EAR is [math]\displaystyle{ (1+{0.1299 \over 365})^{365}-1 }[/math], or 13.87%; and if it is compounded monthly, the one-year EAR is [math]\displaystyle{ (1+{0.1299 \over 12})^{12} - 1 }[/math] or 13.79%. On an annual basis, the one-year EAR for compounding monthly is always less than the EAR for compounding daily. However, the relationship of the two in individual billing periods depends on the APR and the number of days in the billing period.

For example, given twelve billing periods a year, 365 days, and an APR of 12.99%, if a billing period is 28 days then the rate charged by monthly compounding is greater than that charged by daily compounding ([math]\displaystyle{ {0.1299 \over 12} }[/math] is greater than [math]\displaystyle{ (1+{0.1299 \over 365})^{28}-1 }[/math]). But for a billing period of 31 days, the order is reversed ([math]\displaystyle{ {0.1299 \over 12} }[/math] is less than [math]\displaystyle{ (1+{0.1299 \over 365})^{31}-1 }[/math]).

In general, credit cards available to middle-class cardholders that range in credit limit from $1,000 to $30,000 calculate the finance charge by methods that are exactly equal to compound interest compounded daily, although the interest is not posted to the account until the end of the billing cycle. A high U.S. APR of 29.99% carries an effective annual rate of 34.96% for daily compounding and 34.48% for monthly compounding, given a year with twelve billing periods and 365 days.

Table 1 below, given by Prosper (2005), shows data from Experian, one of the three main U.S. and UK credit bureaus (along with Equifax in the UK and TransUnion in the U.S. and internationally). (The data actually come from installment loans [closed end loans], but can also be used as a fair approximation for credit card loans [open end loans]). The table shows the loss rates from borrowers with various credit scores. To get a desired rate of return, a lender would add the desired rate to the loss rate to determine the interest rate. Though individual borrowers differ, lenders predict that, as an aggregate, borrowers will tend to exhibit the same payment behavior that others with similar credit scores have shown in the past. Banks then compete on details by making analyses of how to use data such as these along with any other data they gather from the application and history with the cardholder, to determine an interest rate that will attract borrowers by remaining competitive with other banks and still assure a profit. Debt-to-income ratio (DTI) is another important factor for determining interest rates. The bank calculates it by adding up the borrower's obligated minimum payments on loans, and dividing by the cardholder's income. If it is more than a set point (such as 20% in this example) then loans to that applicant are considered a higher risk than given by this table. These loss rates already include incomes the lenders receive from payments in collection, either from debt collection efforts after default or from selling the loans to third parties for further collection attempts, at a fraction of the amount owed.

| Experian score | Expected annual loss rate (as % of loan balance) |

|---|---|

| 760+ low risk | 0.2 |

| 720-759 | 0.9 |

| 680-719 | 1.8 |

| 640-679 | 3.3 |

| 600-639 | 6.2 |

| 540-599 | 11.1 |

| 540 high risk | 19.1 |

| No credit rating | no data (the lender is on its own) |

To use the chart to make a loan, determine an expected rate of return on the investment (X) and add that to the expected loss rate from the chart. The sum is an approximation of the interest rate that should be contracted with the borrower in order to achieve the expected rate of return.

Banks make many other fees that interrelate with interest charges in complex ways (since they make a profit from the whole combination), including transactions fees paid by merchants and cardholders, and penalty fees, such as for borrowing over the established credit limit, or for failing to make a minimum payment on time.

Banks vary widely in the proportion of credit card account income that comes from interest (depending upon their marketing mix). In a typical United Kingdom card issuer, between 80% and 90% of cardholder generated income is derived from interest charges. A further 10% is made up from default fees.

Laws

Usury

Many nations limit the amount of interest that can be charged (often called usury laws). Most countries strictly regulate the manner in which interest rates are agreed, calculated, and disclosed. Some countries (especially with Muslim influence) prohibit interest being charged at all (and other methods are used, such as an ownership interest taken by the bank in the cardholder's business profits based upon the purchase amount).

United States

Credit CARD Act of 2009

This statute covers several aspects of credit card contracts, including the following:[1]

- Limits over-the-limit fees to cases where the consumer has given permission.

- Limits interest rate increases on past balances to cases in which the account has been over 60 days late.

- Limits general interest rate increases to 45 days after a written notice is given, allowing the consumer to opt out.

- Requires extra payments to be applied to the highest-interest rate sub-balance.

Truth in Lending Act

In the United States, there are four commonly accepted methods of charging interest, which are listed in the section below, "Methods of Charging Interest". These are detailed in Regulation Z of the Truth in Lending Act. There is a legal obligation on U.S. issuers that the method of charging interest is disclosed and is sufficiently transparent to be fair. This is typically done in the Schumer box, which lists rates and terms in writing to the cardholder applicant in a standard format. Regulation Z details four principal methods of calculating interest. For purposes of comparison between rates, the "expected rate" is the APR applied to the average daily balance for a year, or in other words, the interest charged on the actual balance left lent out by the bank at the close of each business day.

That said, there are not just four prescribed ways to charge interest, to wit those specified in Regulation Z. U.S. issuers can charge interest according to any reasonable method to which the card holder agrees. The four (or arguably six) "safe-harbour" ways to describe and charge interest are detailed in Regulation Z. If an issuer charges interest in one of these ways then there is a shorthand description of that method in Regulation Z that can be used. If a lender uses that description, and charges interest in that way, then their disclosure is deemed to be sufficiently transparent and fair. If not, then they must provide an explanation of the method used. Because of the safe-harbour definitions, U.S. lenders have tended to gravitate towards these methods of charging and describing the way interest is charged, both because it is easy and because legal compliance is guaranteed. Arguably, the approach also provides flexibility for issuers, enhancing the profile of the way in which interest is charged, and therefore increasing the scope for product differentiation on what is, after all, a key product feature.

Pre-payment penalties

Clauses calling for a penalty for paying more than the contracted regular payment were once common in another type of loan, the installment loan, and they are of great concern to governments regulating credit card loans. Today, in many cases because of strict laws, most card issuers do not charge any pre-payment penalties at all (except those that come naturally from the interest calculation method – see the section below). That means cardholders can "cancel" the loan at any time by simply paying it off, and be charged no more interest than that calculated on the time the money was borrowed.

Cancelling loans

Cardholders are often surprised in situations where the bank cancels or changes the terms on their loans. Most card issuers are allowed to raise the interest rate (within legal guidelines) at any time. Usually they have to give some notice, such as 30 or 60 days, in writing. If the cardholder does not agree to the new rate or terms, then it is expected that the account will be paid off. That can be difficult for a cardholder with a large loan who expected to make payments over many years. Banks can also cancel a loan and request that all amounts be paid back immediately for any default on the contract whatsoever, which could be as simple as a late payment or even a default on a loan to another bank (the so-called "Universal default") if the contract states it. In some cases, a borrower may cancel the account within the time allowed without paying off the account. As long as the borrower makes no new charges on the account, then the borrower has not "agreed" to the new terms, and may pay off the account under the old terms.

Average daily balance

The sum of the daily outstanding balances is divided by the number of days covered in the cycle to give an average balance for that period. This amount is multiplied by a constant factor to give an interest charge. The resultant interest is the same as if interest was charged at the close of each day, except that it compounds (gets added to the principal) only once per month. It is the simplest of the four methods in the sense that it produces an interest rate approximating if not exactly equal the expected rate.

Adjusted balance

The balance at the end of the billing cycle is multiplied by a factor in order to give the interest charge. This can result in an actual interest rate lower or higher than the expected one, since it does not take into account the average daily balance, i.e. the time value of money actually lent by the bank. It does, however, take into account money that is left lent out over several months.

Previous balance

The reverse happens: the balance at the start of the previous billing cycle is multiplied by the interest factor in order to derive the charge. As with the Adjusted Balance method, this method can result in an interest rate higher or lower than the expected one, but the part of the balance that carries over more than two full cycles is charged at the expected rate.

Two-cycle average daily balance

The sum of the daily balances of the previous two cycles is used, but interest is charged on that amount only over the current cycle. This can result in an actual interest charge that applies the advertised rate to an amount that does not represent the actual amount of money borrowed over time, much different that the expected interest charge. The interest charged on the actual money borrowed over time can vary radically from month-to-month (rather than the APR remaining steady). For example, a cardholder with an average daily balance for the June, July, and August cycles of $100, 1000, 100, will have interest calculated on 550 for July, which is only 55% of the expected interest on 1000, and will have interest calculated on 550 again in August, which is 550% higher than the expected interest on the money actually borrowed over that month, which is 100.

However, when analyzed, the interest on the balance that stays borrowed over the whole time period ($100 in this case) actually does approximate the expected interest rate, just like the other methods, so the variability is only on the balance that varies month-to-month. Therefore, the key to keeping the interest rate stable and close to the "expected rate" (as given by average daily balance method) is to keep the balance close to the same every month. The strategic consumer who has this type of account either pays it all off each month, or makes most charges towards the end of the cycle and payments at the beginning of the cycle to avoid paying too much interest above the expected interest given the interest rate; whereas business cardholders have more sophisticated ways of analyzing and using this type of account for peak cash-flow needs, and willingly pay the "extra" interest to do better business.

Much confusion is caused by and much mis-information given about this method of calculating interest. Because of its complexity for consumers, advisors from Motley Fool (2005) to Credit Advisors (2005) advise consumers to be very wary of this method (unless they can analyze it and achieve true value from it). Despite the confusion of variable interest rates, the bank using this method does have a rationale; that is it costs the bank in strategic opportunity costs to vary the amount loaned from month-to-month, because they have to adjust assets to find the money to loan when it is suddenly borrowed, and find something to do with the money when it is paid back. In that sense, the two-cycle average daily balance can be likened to electric charges for industrial clients, in which the charge is based upon the peak usage rather than the actual usage. And, in fact, this method of charging interest is often used for business cardholders as stated above. These accounts often have much higher credit limits than typically consumer accounts (perhaps tens or hundreds of thousands instead of just thousands).

Daily accrual

The daily accrual method is commonly used in the UK. The annual rate is divided by 365 to give a daily rate. Each day, the balance of the account is multiplied by this rate, and at the end of the cycle the total interest is billed to the account. The effect of this method is theoretically mathematically the same over one year as the average daily balance method, because the interest is compounded monthly, but calculated on daily balances. Although a detailed analysis can be done that shows that the effective interest can be slightly lower or higher each month than with the average daily balance method, depending upon the detailed calculation procedure used and the number of days in each month, the effect over the entire year provides only a trivial opportunity for arbitrage.

Methods and marketing

In effect, differences in methods mostly act upon the fluctuating balance of the most recent cycle (and are almost the same for balances carried over from cycle to cycle. Banks and consumers are aware of transaction costs, and banks actually receive income in the form of per-transaction payments from the merchants, besides gaining a new loan, which is more business for the bank. Therefore, the interest charged in the most recent cycle interrelates with other incomes and benefits to the cardholder and bank, such as transaction cost, transaction fees to the bank, marketing costs for gaining each new loan (which is like a sale for the bank) and marketing costs for overall cardholder perception, which can increase market share. Therefore, the rate charged on the most recent cycle is largely a matter of marketing preference based upon cardholder perceptions, rather than a matter of maximizing the rate.

Bank fee arbitrage and its limits

In general, differences between methods represent a degree of precision over charging the expected interest rate. Precision is important because any detectable difference from the expected rate can theoretically be taken advantage of (through arbitrage) by cardholders (who have control over when to charge and when to pay), to the possible loss of profitability of the bank. However, in effect, the differences between methods are trivial except in terms of cardholder perceptions and marketing, because of transaction costs, transaction income, cash advance fees, and credit limits. While cardholders can certainly affect their overall costs by managing their daily balances (for example, by buying or paying early or late in the month depending upon the calculation method), their opportunities for scaling this arbitrage to make large amounts of money are very limited. For example, in order to charge the maximum on the card, to take maximum advantage of any aribtragable difference in calculation methods, cardholders must actually buy something of that value at the right time, and doing so only to take advantage of a small mathematical discrepancy from the expected rate could be very inconvenient. That adds a cost to each transaction which obscures any benefit that can be gained. Credit limits limit how much can be charged, and thus how much advantage can be taken (trivial amounts), and cash advance fees are charged by banks partially to limit the amount of free movement that can be accomplished. (With no fee cardholders could create any daily balances advantageous to them through a series of cash advances and payments).

Cash rate

Most banks charge a separate, higher interest rate, and a cash advance fee (ranging from 1 to 5% of the amount of cash taken) on cash or cash-like transactions (called "quasi-cash" by many banks). These transactions are usually the ones for which the bank receives no transaction fee from the payee, such as cash from a bank or ATM, casino chips, and some payments to the government (and any transaction that looks in the bank's discretion like a cash swap, such as a payment on multiple invoices). In effect, the interest rate charged on purchases is subsidized by other profits to the bank.

Default rate

Many US banks since 2000 and 2009 had a contractual default rate (in the U.S., 2005, ranging from 10 to 36%), which is typically much higher than the regular APR. The rate took effect automatically if any of the listed conditions occur, which can include the following: one or two late payments, any amount overdue beyond the due date or one more cycle, any returned payment (such as an NSF check), any charging over the credit limit (sometimes including the bank's own fees), and – in some cases – any reduction of credit rating or default with another lender, at the discretion of the bank. In effect, the cardholder is agreeing to pay the default rate on the balance owed unless all the listed events can be guaranteed not to happen. A single late payment, or even a non-reconciled mistake on any account, could result in charges of hundreds or thousands of dollars over the life of the loan. These high effective fees create a great incentive for cardholders to keep track of all their credit card and checking account balances (from which credit card payments are made) and for keeping wide margins (extra money or money available). However, the current lack of provable "account balance ownership" in most credit card and checking account designs (studied between 1990 and 2005) make these kinds of "penalty fees" a complex problem, indeed. New US statutes passed in 2009 limit the use of default rates by allowing an increase in rate on purchases already made only to accounts that have been over 60 days late.

Variable rate

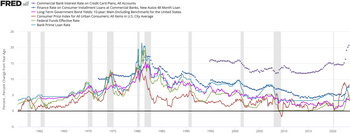

Many credit card issuers give a rate that is based upon an economic indicator published by a respected journal. For example, most banks in the U.S. offer credit cards based upon the lowest U.S. prime rate as published in the Wall Street Journal on the previous business day to the start of the calendar month. For example, a rate given as 9.99% plus the prime rate will be 16.99% when the prime rate is 7.00% (such as the end of 2005). These rates usually also have contractual minimums and maximums to protect the consumer (or the bank, as it may be) from wild fluctuations of the prime rate. While these accounts are harder to budget for, they can theoretically be a little less expensive since the bank does not have to accept the risk of fluctuation of the market (since the prime rate follows inflation rates, which affect the profitability of loans). A fixed rate can be better for consumers who have fixed incomes or need control over their payments budgets. These rates can be varied upon depending upon the policies of different organisations.

Grace period

Many banks provide an exception to their normal method of calculating interest, in which no interest is charged on an ending statement balance that is paid by the due date. Banks have various rules. In some cases the account must be paid off for two months in a row to obtain the discount. If the required amount is not paid, then the normal interest rate calculation method is still used. This allows cardholders to use credit cards for the convenience of the payment method (to have one invoice payable with one check per month rather than many separate cash or check transactions), which allows them to keep money invested at a return until it must be moved to pay the balance, and allows them to keep the float on the money borrowed during each month. The bank, in effect, is marketing the convenience of the payment method (to receive fees and possible new lending income, when the cardholder does not pay), as well as the loans themselves.

Promotional interest rates

Many banks offer very low interest, often 0%, for a certain number of statement cycles on certain sub-balances ranging from the entire balance to purchases or balance transfers (used to pay off other accounts), or only for buying certain merchandise in stores owned or contracted with by the lender.[2] Such "zero interest" credit cards allow participating retailers to generate more sales by encouraging consumers to make more purchases on credit.[3] Additionally, the bank gets a chance to increase income by having more money lent out,[citation needed] and possibly an extra marketing transaction payment, either from the payee or sales side of the business, for contributing to the sale (in some cases as much as the entire interest payment, charged to the payee instead of the cardholder).[4]

These offers are often complex, requiring the cardholder to work to understand the terms of the offer, and possibly to pay off the sub-balance by a certain date or have interest charged retro-actively, or to pay a certain amount per month over the minimum due (an "interest free" minimum payment) in order to pay down the sub-balance. Methods for communicating the sub-balances and rules on statements vary widely and do not usually conform to any standard. For example, sub-balances are not always reconcilable with the bank (due to lack of debit and credit statements on those balances), and even the term "cycle" (for number of cycles) is not often defined in writing by the bank. Banks also allocate payments automatically to sub-balances in various, often obscure ways. For example, they may contractually pay off promotional balances before higher-interest balances (causing the higher interest to be charged until the account is paid off in full.) These methods, besides possibly saving the cardholder money over the expected interest rate, serve to obscure the actual rate charged by the bank. For example, consumers may think they are paying zero percent, when the actual calculated amount on their daily balances is much more.[5]

When a "promotional" rate expires, normal balance transfer rate would apply and significant increase in interest charges could accrue and may be greater than they were prior to initiating a balance transfer.

Stoozing

Stoozing is the act of borrowing money at an interest rate of 0%, a rate typically offered by credit card companies as an incentive for new customers.[6] The money is then placed in a high interest bank account to make a profit from the interest earned. The borrower (or "stoozer") then pays the money back before the 0% period ends.[7] The borrower does not typically have a real debt to service, but instead uses the money loaned to them to earn interest. Stoozing can also be viewed as a form of arbitrage.

Rewards programs

The term "rewards program" is a term used by card issuers to refer to offers (first used by Discover Card in 1985) to share transactions fees with the cardholder through various games and bonus programs. Cardholders typically receive one "point", "mile" or actual penny (1% of the transaction) for each dollar spent on the card,[8] and more points for buying from certain types of merchants or cooperating merchants, and then can pay down the loan, or trade points for airline flights, catalog merchandise, lower interest rates, gift cards, or cash. The points can also be exchanged, sometimes, between cooperating programs of different banks, making them more and more currency-like. These programs represent such a large value that they are not-completely-jokingly considered a set of currencies. These combined "currencies" have accumulated to the point that they hold more value worldwide than U.S. (paper) dollars, and are the subject of company liquidation disputes and divorce settlements (Economist, 2005). They are criticized for being highly inflationary, and subject to the whims of the card issuers (raising the prices after the points are earned). Many cardholders get a new card or use a card for the points, but later forget or decline to use the points, anyway. While opening new avenues for marketing and competition, rewards programs are criticized in terms of being able to compare interest rates by making it impossible for consumers to compare one competitive interest rate offer to another through any standard means such as under the U.S. Truth in Lending Act, because of the extra value offered by the bonus program, along with other terms, costs, and benefits created by other marketing gimmicks such as the ones cited in this article.

References

- ↑ "Text of H.R. 627 (111th)". Govtrack.us. http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr627/text. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ↑ Warwick, Jacquelyn; Mansfield, Phylis (December 2000). "Credit card consumers: college students? knowledge and attitude". Journal of Consumer Marketing 17 (7): 617–626. doi:10.1108/07363760010357813.

- ↑ "How Do Zero Interest Credit Cards Work?". Practical Financial Tips. http://www.practicalfinancialtips.com/credit-card/how-do-zero-interest-credit-cards-work/. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- ↑ Calem, Paul S.; Mester, Loretta J. (1995). "Consumer Behavior and the Stickiness of Credit-Card Interest Rates". The American Economic Review 85 (5): 1327–1336.

- ↑ Hans, McClan (29 August 2021). "Creditcardmaatschappij ICS (ABN Amro) krijgt forse boete" (in nl-NL). Cashwhale. https://www.cashwhale.nl/2021/08/29/creditcardaanbieder-ics-krijgt-forse-boete/. Retrieved 29 August 2021.

- ↑ "'You can avoid paying interest altogether'". The Telegraph. 10 November 2004. ISSN 0307-1235. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/personalfinance/2899156/You-can-avoid-paying-interest-altogether.html. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

- ↑ Stepek, John (22 October 2007). "How 'stoozing' could bring down the global economy – MoneyWeek". MoneyWeek. https://moneyweek.com/19017/how-stoozing-could-bring-down-the-global-economy/. Retrieved 2018-11-02.

- ↑ "How You Can Find the Right Rewards Credit Card". https://www.investopedia.com/what-is-a-rewards-credit-card-5071957#:~:text=Rewards%20credit%20cards%20offer%20you,in%20a%20variety%20of%20ways.

|