Dynamic epistemic logic

Dynamic epistemic logic (DEL) is a logical framework dealing with knowledge and information change. Typically, DEL focuses on situations involving multiple agents and studies how their knowledge changes when events occur. These events can change factual properties of the actual world (they are called ontic events): for example a red card is painted in blue. They can also bring about changes of knowledge without changing factual properties of the world (they are called epistemic events): for example a card is revealed publicly (or privately) to be red. Originally, DEL focused on epistemic events. We only present in this entry some of the basic ideas of the original DEL framework; more details about DEL in general can be found in the references. Due to the nature of its object of study and its abstract approach, DEL is related and has applications to numerous research areas, such as computer science (artificial intelligence), philosophy (formal epistemology), economics (game theory) and cognitive science. In computer science, DEL is for example very much related to multi-agent systems, which are systems where multiple intelligent agents interact and exchange information.

As a combination of dynamic logic and epistemic logic, dynamic epistemic logic is a young field of research. It really started in 1989 with Plaza's logic of public announcement.[1] Independently, Gerbrandy and Groeneveld[2] proposed a system dealing moreover with private announcement and that was inspired by the work of Veltman.[3] Another system was proposed by van Ditmarsch whose main inspiration was the Cluedo game.[4] But the most influential and original system was the system proposed by Baltag, Moss and Solecki.[5][6] This system can deal with all the types of situations studied in the works above and its underlying methodology is conceptually grounded. We will present in this entry some of its basic ideas.

Formally, DEL extends ordinary epistemic logic by the inclusion of event models to describe actions, and a product update operator that defines how epistemic models are updated as the consequence of executing actions described through event models. Epistemic logic will first be recalled. Then, actions and events will enter into the picture and we will introduce the DEL framework.[7]

Epistemic Logic

Epistemic logic is a modal logic dealing with the notions of knowledge and belief. As a logic, it is concerned with understanding the process of reasoning about knowledge and belief: which principles relating the notions of knowledge and belief are intuitively plausible? Like epistemology, it stems from the Greek word [math]\displaystyle{ \epsilon\pi\iota\sigma\tau\eta\mu\eta }[/math] or ‘episteme’ meaning knowledge. Epistemology is nevertheless more concerned with analyzing the very nature and scope of knowledge, addressing questions such as “What is the definition of knowledge?” or “How is knowledge acquired?”. In fact, epistemic logic grew out of epistemology in the Middle Ages thanks to the efforts of Burley and Ockham.[8] The formal work, based on modal logic, that inaugurated contemporary research into epistemic logic dates back only to 1962 and is due to Hintikka.[9] It then sparked in the 1960s discussions about the principles of knowledge and belief and many axioms for these notions were proposed and discussed.[10] For example, the interaction axioms [math]\displaystyle{ K p\rightarrow B p }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B p\rightarrow KB p }[/math] are often considered to be intuitive principles: if an agent Knows [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] then (s)he also Believes [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math], or if an agent Believes [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math], then (s)he Knows that (s)he Believes [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]. More recently, these kinds of philosophical theories were taken up by researchers in economics,[11] artificial intelligence and theoretical computer science[12] where reasoning about knowledge is a central topic. Due to the new setting in which epistemic logic was used, new perspectives and new features such as computability issues were then added to the research agenda of epistemic logic.

Syntax

In the sequel, [math]\displaystyle{ AGTS=\{1,\ldots,n\} }[/math] is a finite set whose elements are called agents and [math]\displaystyle{ PROP }[/math] is a set of propositional letters.

The epistemic language is an extension of the basic multi-modal language of modal logic with a common knowledge operator [math]\displaystyle{ C_{A} }[/math] and a distributed knowledge operator [math]\displaystyle{ D_{A} }[/math]. Formally, the epistemic language [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}_{\textsf{EL}}^{C} }[/math] is defined inductively by the following grammar in BNF:

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}_{\textsf{EL}}^{C}:\phi~~::=~~ p~\mid~\neg\phi~\mid~(\phi\land\phi)~\mid~ K_j\phi~\mid~ C_{A}\phi ~\mid~ D_{A}\phi }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ p\in PROP }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ j\in {AGTS} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ A\subseteq {AGTS} }[/math]. The basic epistemic language [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}_{EL} }[/math] is the language [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}_{EL}^{C} }[/math] without the common knowledge and distributed knowledge operators. The formula [math]\displaystyle{ \bot }[/math] is an abbreviation for [math]\displaystyle{ \neg p \land p }[/math] (for a given [math]\displaystyle{ p\in PROP }[/math]), [math]\displaystyle{ \langle K_{j}\rangle\phi }[/math] is an abbreviation for [math]\displaystyle{ \neg K_j\neg\phi }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ E_{A}\phi }[/math] is an abbreviation for [math]\displaystyle{ \bigwedge\limits_{j\in A} K_j\phi }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ C\phi }[/math] an abbreviation for [math]\displaystyle{ C_{AGTS}\phi }[/math].

Group notions: general, common and distributed knowledge.

In a multi-agent setting there are three important epistemic concepts: general knowledge, distributed knowledge and common knowledge. The notion of common knowledge was first studied by Lewis in the context of conventions.[13] It was then applied to distributed systems[12] and to game theory,[14] where it allows to express that the rationality of the players, the rules of the game and the set of players are commonly known.

General knowledge.

General knowledge of [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] means that everybody in the group of agents [math]\displaystyle{ {AGTS} }[/math] knows that [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math]. Formally, this corresponds to the following formula:

[math]\displaystyle{ E\phi:=\underset{j\in {AGTS}}\bigwedge K_j\phi. }[/math]

Common knowledge.

Common knowledge of [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] means that everybody knows [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] but also that everybody knows that everybody knows [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math], that everybody knows that everybody knows that everybody knows [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math], and so on ad infinitum. Formally, this corresponds to the following formula

[math]\displaystyle{ C\phi:=E\phi\land E E\phi\land E E E\phi\land\ldots }[/math]

As we do not allow infinite conjunction the notion of common knowledge will have to be introduced as a primitive in our language.

Before defining the language with this new operator, we are going to give an example introduced by Lewis that illustrates the difference between the notions of general knowledge and common knowledge. Lewis wanted to know what kind of knowledge is needed so that the statement [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]: “every driver must drive on the right” be a convention among a group of agents. In other words, he wanted to know what kind of knowledge is needed so that everybody feels safe to drive on the right. Suppose there are only two agents [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math]. Then everybody knowing [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] (formally [math]\displaystyle{ E p }[/math]) is not enough. Indeed, it might still be possible that the agent [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] considers possible that the agent [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] does not know [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] (formally [math]\displaystyle{ \neg K_i K_j p }[/math]). In that case the agent [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] will not feel safe to drive on the right because he might consider that the agent [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math], not knowing [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math], could drive on the left. To avoid this problem, we could then assume that everybody knows that everybody knows that [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] (formally [math]\displaystyle{ E E p }[/math]). This is again not enough to ensure that everybody feels safe to drive on the right. Indeed, it might still be possible that agent [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] considers possible that agent [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] considers possible that agent [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] does not know [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] (formally [math]\displaystyle{ \neg K_i K_j K_i p }[/math]). In that case and from [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]’s point of view, [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] considers possible that [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math], not knowing [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math], will drive on the left. So from [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math]’s point of view, [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] might drive on the left as well (by the same argument as above). So [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] will not feel safe to drive on the right. Reasoning by induction, Lewis showed that for any [math]\displaystyle{ k\in \mathbb{N} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ E p\land E^1 p\land \ldots \land E^k p }[/math] is not enough for the drivers to feel safe to drive on the right. In fact what we need is an infinite conjunction. In other words, we need common knowledge of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]: [math]\displaystyle{ C p }[/math].

Distributed knowledge.

Distributed knowledge of [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] means that if the agents pulled their knowledge altogether, they would know that [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] holds. In other words, the knowledge of [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] is distributed among the agents. The formula [math]\displaystyle{ D_{A}\phi }[/math] reads as ‘it is distributed knowledge among the set of agents [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] that [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] holds’.

Semantics

Epistemic logic is a modal logic. So, what we call an epistemic model [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M}=(W, R_1,\ldots, R_n,I) }[/math] is just a Kripke model as defined in modal logic. The set [math]\displaystyle{ W }[/math] is a non-empty set whose elements are called possible worlds and the interpretation [math]\displaystyle{ I:W\rightarrow 2^{PROP} }[/math] is a function specifying which propositional facts (such as ‘Ann has the red card’) are true in each of these worlds. The accessibility relations [math]\displaystyle{ R_j\subseteq W\times W }[/math] are binary relations for each agent [math]\displaystyle{ j\in AGTS }[/math]; they are intended to capture the uncertainty of each agent (about the actual world and about the other agents' uncertainty). Intuitively, we have [math]\displaystyle{ (w,v)\in R_j }[/math] when the world [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] is compatible with agent [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math]’s information in world [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] or, in other words, when agent [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] considers that world [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] might correspond to the world [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] (from this standpoint). We abusively write [math]\displaystyle{ w\in\mathcal{M} }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ w\in W }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ R_j(w) }[/math] denotes the set of worlds [math]\displaystyle{ \{v\in W; (w,v)\in R_j\} }[/math].

Intuitively, a pointed epistemic model [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{M},w) }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ w\in\mathcal{M} }[/math], represents from an external point of view how the actual world [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] is perceived by the agents [math]\displaystyle{ {AGTS} }[/math].

For every epistemic model [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M} }[/math], every [math]\displaystyle{ w\in \mathcal{M} }[/math] and every [math]\displaystyle{ \phi\in\mathcal{L}_{\textsf{EL}} }[/math], we define [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models\phi }[/math] inductively by the following truth conditions:

| [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models p }[/math] | iff | [math]\displaystyle{ p\in I(w) }[/math] |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models \neg\phi }[/math] | iff | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{it~is~not~the~case~that~}\mathcal{M},w\models\phi }[/math] |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models \phi\land\psi }[/math] | iff | [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models\phi\textrm{~and~}\mathcal{M},w\models\psi }[/math] |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models K_j\phi }[/math] | iff | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{for~all~} v\in R_j(w), \mathcal{M},v\models\phi }[/math] |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models C_{A}\phi }[/math] | iff | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{for~all~}v\in \left(\underset{j\in A}{\bigcup}R_j\right)^+(w), \mathcal{M},v\models\phi }[/math] |

| [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models D_{A}\phi }[/math] | iff | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{for~all~}v\in \underset{j\in A}{\bigcap}R_j (w), \mathcal{M},v\models\phi }[/math] |

where [math]\displaystyle{ \left(\underset{j\in A}{\bigcup}R_j\right)^+ }[/math] is the transitive closure of [math]\displaystyle{ \underset{j\in A}{\bigcup}R_j }[/math]: we have that [math]\displaystyle{ v\in\left(\underset{j\in A}{\bigcup}R_j\right)^+(w) }[/math] if, and only if, there are [math]\displaystyle{ w_0,\ldots,w_m\in\mathcal{M} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j_1,\ldots,j_m\in A }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ w_0=w, w_m=v }[/math] and for all [math]\displaystyle{ i\in\{1,\ldots,m\} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ w_{i-1} R_{j_i} w_i }[/math].

Despite the fact that the notion of common belief has to be introduced as a primitive in the language, we can notice that the definition of epistemic models does not have to be modified in order to give truth value to the common knowledge and distributed knowledge operators.

Card Example:

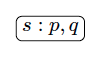

Players [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] (standing for Ann, Bob and Claire) play a card game with three cards: a red one, a green one and a blue one. Each of them has a single card but they do not know the cards of the other players. Ann has the red card, Bob has the green card and Claire has the blue card. This example is depicted in the pointed epistemic model [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{M},w) }[/math] represented below. In this example, [math]\displaystyle{ AGTS:=\{A,B,C\} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ PROP:=\{{\color{red}{A}},{\color{green}{B}},{\color{blue}{C}},{\color{red}{B}},{\color{green}{C}},{\color{blue}{A}},{\color{red}{C}},{\color{green}{A}},{\color{blue}{B}}\} }[/math]. Each world is labelled by the propositional letters which are true in this world and [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] corresponds to the actual world. There is an arrow indexed by agent [math]\displaystyle{ j\in\{A,B,C\} }[/math] from a possible world [math]\displaystyle{ u }[/math] to a possible world [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] when [math]\displaystyle{ (u,v)\in R_j }[/math]. Reflexive arrows are omitted, which means that for all [math]\displaystyle{ j\in \{A,B,C\} }[/math] and all [math]\displaystyle{ v\in \mathcal{M} }[/math], we have that [math]\displaystyle{ (v,v)\in R_j }[/math].

[math]\displaystyle{ {\color{red}{A}} }[/math] stands for : "[math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] has the red card''

[math]\displaystyle{ {\color{blue}{C}} }[/math] stand for: "[math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] has the blue card''

[math]\displaystyle{ {\color{green}{B}} }[/math] stands for: "[math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] has the green card''

and so on...

When accessibility relations are equivalence relations (like in this example) and we have that [math]\displaystyle{ (w,v)\in R_j }[/math], we say that agent [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] cannot distinguish world [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] from world [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] (or world [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] is indistinguishable from world [math]\displaystyle{ v }[/math] for agent [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math]). So, for example, [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] cannot distinguish the actual world [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] from the possible world where [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] has the blue card ([math]\displaystyle{ {\color{blue}{B}} }[/math]), [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] has the green card ([math]\displaystyle{ {\color{green}{C}} }[/math]) and [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] still has the red card ([math]\displaystyle{ {\color{red}{A}} }[/math]).

In particular, the following statements hold:

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models({\color{red}{A}}\land K_A{\color{red}{A}})\land({\color{blue}{C}}\land K_C{\color{blue}{C}})\land ({\color{green}{B}}\land K_B{\color{green}{B}}) }[/math]

'All the agents know the color of their card'.

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models K_A({\color{blue}{B}}\vee{\color{green}{B}})\land K_A({\color{blue}{C}}\vee{\color{green}{C}}) }[/math]

'[math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] knows that [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] has either the blue or the green card and that [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] has either the blue or the green card'.

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models E({\color{red}{A}}\vee{\color{blue}{A}}\vee{\color{green}{A}})\land C({\color{red}{A}}\vee{\color{blue}{A}}\vee{\color{green}{A}}) }[/math]

'Everybody knows that [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] has either the red, green or blue card and this is even common knowledge among all agents'.

Knowledge versus Belief

We use the same notation [math]\displaystyle{ K_j }[/math] for both knowledge and belief. Hence, depending on the context, [math]\displaystyle{ K_j\phi }[/math] will either read ‘the agent [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] Knows that [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] holds’ or ‘the agent [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] Believes that [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] holds’. A crucial difference is that, unlike knowledge, beliefs can be wrong: the axiom [math]\displaystyle{ K_j\phi\rightarrow \phi }[/math] holds only for knowledge, but not necessarily for belief. This axiom called axiom T (for Truth) states that if the agent knows a proposition, then this proposition is true. It is often considered to be the hallmark of knowledge and it has not been subjected to any serious attack ever since its introduction in the Theaetetus by Plato.

The notion of knowledge might comply to some other constraints (or axioms) such as [math]\displaystyle{ K_j\phi\rightarrow K_j K_j\phi }[/math]: if agent [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] knows something, she knows that she knows it. These constraints might affect the nature of the accessibility relations [math]\displaystyle{ R_j }[/math] which may then comply to some extra properties. So, we are now going to define some particular classes of epistemic models that all add some extra constraints on the accessibility relations [math]\displaystyle{ R_j }[/math]. These constraints are matched by particular axioms for the knowledge operator [math]\displaystyle{ K_j }[/math]. Below each property, we give the axiom which defines[15] the class of epistemic frames that fulfill this property. ([math]\displaystyle{ K\phi }[/math] stands for [math]\displaystyle{ K_j\phi }[/math] for any [math]\displaystyle{ j\in AGTS }[/math].)

| serial | [math]\displaystyle{ R(w)\neq\emptyset }[/math] |

| D | [math]\displaystyle{ K\phi\rightarrow \langle K\rangle\phi }[/math] |

| transitive | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{If }~w'\in R(w) ~\textrm{ and }~ w''\in R(w'), ~\textrm{ then}~ w''\in R(w) }[/math] |

| 4 | [math]\displaystyle{ K\phi\rightarrow KK\phi }[/math] |

| Euclidicity | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{If }~ w'\in R(w) ~\textrm{ and }~ w''\in R(w), ~\textrm{ then }~ w'\in R(w'') }[/math] |

| 5 | [math]\displaystyle{ \neg K \phi\rightarrow K \neg K\phi }[/math] |

| reflexive | [math]\displaystyle{ w\in R(w) }[/math] |

| T | [math]\displaystyle{ K\phi\rightarrow \phi }[/math] |

| symmetric | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{If }~ w'\in R(w), ~\textrm{ then }~ w\in R(w') }[/math] |

| B | [math]\displaystyle{ \phi\rightarrow K\neg K\neg\phi }[/math] |

| confluent | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{If }~ w'\in R(w) \textrm{~and~} w''\in R(w), \textrm{then~there~is~} v \textrm{~such~ that }~ v\in R(w') \textrm{~and~} v\in R(w'') }[/math] |

| .2 | [math]\displaystyle{ \langle K\rangle K\phi\rightarrow K\langle K\rangle\phi }[/math] |

| weakly connected | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{If }~ w'\in R(w) \textrm{~and~} w''\in R(w), \textrm{~then~} w'=w'' \textrm{~or~} w'\in R(w'') \textrm{~or~} w''\in R(w') }[/math] |

| .3 | [math]\displaystyle{ \langle K\rangle\phi\land\langle K\rangle\psi\rightarrow \langle K\rangle(\phi\land\psi)\vee\langle K\rangle(\psi\land\langle K\rangle\phi)\vee\langle K\rangle(\phi\land\langle K\rangle\psi) }[/math] |

| semi-Euclidean | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{If~} w''\in R(w) \textrm{~and~} w\notin R(w'') \textrm{~and~} w'\in R(w), \textrm{~then~} w''\in R(w') }[/math] |

| .3.2 | [math]\displaystyle{ (\langle K\rangle\phi\land\langle K\rangle K\psi)\rightarrow K(\langle K\rangle\phi\vee\psi) }[/math] |

| R1 | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{If~} w''\in R(w) \textrm{~and~} w\neq w'' \textrm{~and~} w'\in R(w), \textrm{~then~} w''\in R(w') }[/math] |

| .4 | [math]\displaystyle{ (\phi\land\langle K\rangle K \phi)\rightarrow K\phi }[/math] |

We discuss the axioms above. Axiom 4 states that if the agent knows a proposition, then she knows that she knows it (this axiom is also known as the “KK-principle”or “KK-thesis”). In epistemology, axiom 4 tends to be accepted by internalists, but not by externalists.[16] Axiom 4 is nevertheless widely accepted by computer scientists (but also by many philosophers, including Plato, Aristotle, Saint Augustine, Spinoza and Schopenhauer, as Hintikka recalls ). A more controversial axiom for the logic of knowledge is axiom 5 for Euclidicity: this axiom states that if the agent does not know a proposition, then she knows that she does not know it. Most philosophers (including Hintikka) have attacked this axiom, since numerous examples from everyday life seem to invalidate it.[17] In general, axiom 5 is invalidated when the agent has mistaken beliefs, which can be due for example to misperceptions, lies or other forms of deception. Axiom B states that it cannot be the case that the agent considers it possible that she knows a false proposition (that is, [math]\displaystyle{ \neg(\neg\phi\land\neg K\neg K\phi) }[/math]). If we assume that axioms T and 4 are valid, then axiom B falls prey to the same attack as the one for axiom 5 since this axiom is derivable. Axiom D states that the agent's beliefs are consistent. In combination with axiom K (where the knowledge operator is replaced by a belief operator), axiom D is in fact equivalent to a simpler axiom D' which conveys, maybe more explicitly, the fact that the agent's beliefs cannot be inconsistent: [math]\displaystyle{ \neg B \bot }[/math]. The other intricate axioms .2, .3, .3.2 and .4 have been introduced by epistemic logicians such as Lenzen and Kutchera in the 1970s[10][18] and presented for some of them as key axioms of epistemic logic. They can be characterized in terms of intuitive interaction axioms relating knowledge and beliefs.[19]

Axiomatization

The Hilbert proof system K for the basic modal logic is defined by the following axioms and inference rules: for all [math]\displaystyle{ j\in AGTS }[/math],

| Prop | All axioms and inference rules of propositional logic |

| K | [math]\displaystyle{ K_j(\phi\rightarrow\psi)\rightarrow(K_j\phi\rightarrow K_j\psi) }[/math] |

| Nec | If [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ K_j\phi }[/math] |

The axioms of an epistemic logic obviously display the way the agents reason. For example, the axiom K together with the rule of inference Nec entail that if I know [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ K\phi }[/math]) and I know that [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] implies [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ K(\phi\rightarrow \psi)) }[/math] then I know that [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] ([math]\displaystyle{ K\psi }[/math]). Stronger constraints can be added. The following proof systems for [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}_{\textsf{EL}} }[/math] are often used in the literature.

| KD45 | = | K+D+4+5 | S4.2 | = | S4+.2 | S4.3.2 | = | S4+.3.2 | S5 | = | S4+5 | |||||||||

| S4 | = | K+T+4 | S4.3 | = | S4+.3 | S4.4 | = | S4+.4 | Br | = | K+T+B |

We define the set of proof systems [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{L}_{\textsf{EL}}:=\{\textsf{K}, \textsf{KD45},\textsf{S4},\textsf{S4.2},\textsf{S4.3},\textsf{S4.3.2},\textsf{S4.4},\textsf{S5}\} }[/math].

Moreover, for all [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H}\in\mathbb{L}_{\textsf{EL}} }[/math], we define the proof system [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H}^{\textsf{C}} }[/math] by adding the following axiom schemes and rules of inference to those of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H} }[/math]. For all [math]\displaystyle{ A\subseteq AGTS }[/math],

| Dis | [math]\displaystyle{ K_j\phi\rightarrow D_A\phi }[/math] |

| Mix | [math]\displaystyle{ C_{A}\phi\rightarrow E_{A}(\phi\land C_{A}\phi) }[/math] |

| Ind | [math]\displaystyle{ \textrm{if~} \phi\rightarrow E_{A}(\psi\land\phi) \textrm{~then~} \phi\rightarrow C_{A}\psi }[/math] |

The relative strength of the proof systems for knowledge is as follows:

[math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{S4}\subset \textsf{S4.2}\subset \textsf{S4.3}\subset\textsf{S4.3.2}\subset\textsf{S4.4}\subset \textsf{S5}. }[/math]

So, all the theorems of [math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{S4.2} }[/math] are also theorems of [math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{S4.3}, \textsf{S4.3.2}, \textsf{S4.4} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{S5} }[/math]. Many philosophers claim that in the most general cases, the logic of knowledge is [math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{S4.2} }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{S4.3} }[/math].[18][20] Typically, in computer science and in many of the theories developed in artificial intelligence, the logic of belief (doxastic logic) is taken to be [math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{KD45} }[/math] and the logic of knowledge (epistemic logic) is taken to be [math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{S5} }[/math], even if [math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{S5} }[/math] is only suitable for situations where the agents do not have mistaken beliefs.[17] [math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{Br} }[/math] has been propounded by Floridi as the logic of the notion of 'being informed’ which mainly differs from the logic of knowledge by the absence of introspection for the agents.[21]

For all [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H}\in\mathbb{L}_{\textsf{EL}} }[/math], the class of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H} }[/math]–models or [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H}^{\textsf{C}} }[/math]–models is the class of epistemic models whose accessibility relations satisfy the properties listed above defined by the axioms of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H} }[/math] or [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H}^{\textsf{C}} }[/math]. Then, for all [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H}\in\mathbb{L}_{\textsf{EL}} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H} }[/math] is sound and strongly complete for [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}_{\textsf{EL}} }[/math] w.r.t. the class of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H} }[/math]–models, and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H}^{\textsf{C}} }[/math] is sound and strongly complete for [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}_{\textsf{EL}}^{\textsf{C}} }[/math] w.r.t. the class of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H}^{\textsf{C}} }[/math]–models.

Decidability and Complexity

The satisfiability problem for all the logics introduced is decidable. We list below the computational complexity of the satisfiability problem for each of them. Note that it becomes linear in time if there are only finitely many propositional letters in the language. For [math]\displaystyle{ n\geq 2 }[/math], if we restrict to finite nesting, then the satisfiability problem is NP-complete for all the modal logics considered. If we then further restrict the language to having only finitely many primitive propositions, the complexity goes down to linear in time in all cases.[22][23]

| Logic | [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math] | [math]\displaystyle{ n\geq 2 }[/math] | with common knowledge |

|---|---|---|---|

| K, S4 | PSPACE | PSPACE | EXPTIME |

| KD45 | NP | PSPACE | EXPTIME |

| S5 | NP | PSPACE | EXPTIME |

The computational complexity of the model checking problem is in P in all cases.

Adding Dynamics

Dynamic Epistemic Logic (DEL) is a logical framework for modeling epistemic situations involving several agents, and changes that occur to these situations as a result of incoming information or more generally incoming action. The methodology of DEL is such that it splits the task of representing the agents’ beliefs and knowledge into three parts:

- One represents their beliefs about an initial situation thanks to an epistemic model;

- One represents their beliefs about an event taking place in this situation thanks to an event model;

- One represents the way the agents update their beliefs about the situation after (or during) the occurrence of the event thanks to a product update.

Typically, an informative event can be a public announcement to all the agents of a formula [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math]: this public announcement and correlative update constitute the dynamic part. However, epistemic events can be much more complex than simple public announcement, including hiding information for some of the agents, cheating, lying, bluffing, etc. This complexity is dealt with when we introduce the notion of event model. We will first focus on public announcements to get an intuition of the main underlying ideas of DEL.

Public Events

In this section, we assume that all events are public. We start by giving a concrete example where DEL can be used, to better understand what is going on. This example is called the muddy children puzzle. Then, we will present a formalization of this puzzle in a logic called Public Announcement Logic (PAL). The muddy children puzzle is one of the most well known puzzles that played a role in the development of DEL. Other significant puzzles include the sum and product puzzle, the Monty Hall dilemma, the Russian cards problem, the two envelopes problem, Moore's paradox, the hangman paradox, etc.[24]

Muddy Children Example:

We have two children, A and B, both dirty. A can see B but not himself, and B can see A but not herself. Let [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] be the proposition stating that A is dirty, and [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] be the proposition stating that B is dirty.

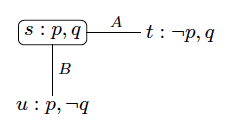

- We represent the initial situation by the pointed epistemic model [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{N},s) }[/math] represented below, where relations between worlds are equivalence relations. States [math]\displaystyle{ s,t,u,v }[/math] intuitively represent possible worlds, a proposition (for example [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math]) satisfiable at one of these worlds intuitively means that in the corresponding possible world, the intuitive interpretation of [math]\displaystyle{ p }[/math] (A is dirty) is true. The links between worlds labelled by agents (A or B) intuitively express a notion of indistinguishability for the agent at stake between two possible worlds. For example, the link between [math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] labelled by A intuitively means that A can not distinguish the possible world [math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math] from [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] and vice versa. Indeed, A cannot see himself, so he cannot distinguish between a world where he is dirty and one where he is not dirty. However, he can distinguish between worlds where B is dirty or not because he can see B. With this intuitive interpretation we are brought to assume that our relations between worlds are equivalence relations.

- Now, suppose that their father comes and announces that at least one is dirty (formally, [math]\displaystyle{ p\vee q }[/math]). Then we update the model and this yields the pointed epistemic model represented below. What we actually do is suppressing the worlds where the content of the announcement is not fulfilled. In our case this is the world where [math]\displaystyle{ \neg p }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \neg q }[/math] are true. This suppression is what we call the update. We then get the model depicted below. As a result of the announcement, both A and B do know that at least one of them is dirty. We can read this from the epistemic model.

- Now suppose there is a second (and final) announcement that says that neither knows they are dirty (an announcement can express facts about the situation as well as epistemic facts about the knowledge held by the agents). We then update similarly the model by suppressing the worlds which do not satisfy the content of the announcement, or equivalently by keeping the worlds which do satisfy the announcement. This update process thus yields the pointed epistemic model represented below. By interpreting this model, we get that A and B both know that they are dirty, which seems to contradict the content of the announcement. However, if we assume that A and B are both perfect reasoners and that this is common knowledge among them, then this inference makes perfect sense.

Public announcement logic (PAL):

We present the syntax and semantic of Public Announcement Logic (PAL), which combines features of epistemic logic and propositional dynamic logic.[25]

We define the language [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal{L}_{PAL}} }[/math] inductively by the following grammar in BNF:

[math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal{L}_{PAL}}:\phi~~::=~~ p~\mid~\neg\phi~\mid~(\phi\land\phi)~\mid~K_j\phi~\mid~[\phi!]\phi }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ j\in AGTS }[/math].

The language [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal{L}_{PAL}} }[/math] is interpreted over epistemic models. The truth conditions for the connectives of the epistemic language are the same as in epistemic logic (see above). The truth condition for the new dynamic action modality [math]\displaystyle{ [\psi!]\phi }[/math] is defined as follows:

| [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models [\psi!]\phi }[/math] | iff | [math]\displaystyle{ \mbox{if } \mathcal{M},w\models\psi\mbox{ then } \mathcal{M}^\psi,w\models\phi }[/math] |

where [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M}^\psi:=(W^\psi,R_1^\psi,\ldots, R_n^\psi,I^\psi) }[/math] with

[math]\displaystyle{ W^\psi:=\{w\in W; \mathcal{M},w\models\psi\} }[/math],

[math]\displaystyle{ R_j^\psi:=R_j\cap (W^\psi\times W^\psi) }[/math] for all [math]\displaystyle{ j\in\{1,\ldots,n\} }[/math] and

[math]\displaystyle{ I^\psi(w):=I(w)\textrm{~for~all~} w\in W^{\psi} }[/math].

The formula [math]\displaystyle{ [\psi!]\phi }[/math] intuitively means that after a truthful announcement of [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \phi }[/math] holds. A public announcement of a proposition [math]\displaystyle{ \psi }[/math] changes the current epistemic model like in the figure below.

The proof system [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H}_{PAL} }[/math] defined below is sound and strongly complete for [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal{L}_{PAL}} }[/math] w.r.t. the class of all pointed epistemic models.

| [math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{K} }[/math] | The Axioms and the rules of inference of the proof system [math]\displaystyle{ \textsf{K} }[/math](see above) | |

| Red 1 | [math]\displaystyle{ [\psi!] p\leftrightarrow (\psi \rightarrow p) }[/math] | |

| Red 2 | [math]\displaystyle{ [\psi!]\neg \phi \leftrightarrow (\psi \rightarrow \neg [\psi!]\phi) }[/math] | |

| Red 3 | [math]\displaystyle{ [\psi!](\phi \land \chi) \leftrightarrow ([\psi!]\phi \land [\psi!]\chi) }[/math] | |

| Red 4 | [math]\displaystyle{ [\psi!] K_i\phi \leftrightarrow \left(\psi \rightarrow K_i (\psi\rightarrow [\psi!]\phi)\right) }[/math] |

The axioms Red 1 - Red 4 are called reduction axioms because they allow to reduce any formula of [math]\displaystyle{ {\mathcal{L}_{PAL}} }[/math] to a provably equivalent formula of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}_{EL} }[/math] in [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H}_{PAL} }[/math]. The formula [math]\displaystyle{ [q!]K q }[/math] is a theorem provable in [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{H}_{PAL} }[/math]. It states that after a public announcement of [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math], the agent knows that [math]\displaystyle{ q }[/math] holds.

PAL is decidable, its model checking problem is solvable in polynomial time and its satisfiability problem is PSPACE-complete.[26]

Muddy children puzzle formalized with PAL:

Here are some of the statements that hold in the muddy children puzzle formalized in PAL.

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{N},s\models p\land q }[/math]

'In the initial situation, A is dirty and B is dirty'.

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{N},s\models(\neg K_Ap\land \neg K_A\neg p)\land (\neg K_B q \land\neg K_B\neg q) }[/math]

'In the initial situation, A does not know whether he is dirty and B neither'.

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{N},s\models[p\vee q!](K_A(p\vee q)\land K_B(p\vee q)) }[/math]

'After the public announcement that at least one of the children A and B is dirty, both of them know that at least one of them is dirty'. However:

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{N},s\models[p\vee q!]((\neg K_Ap\land \neg K_A\neg p)\land (\neg K_B q \land\neg K_B\neg q)) }[/math]

'After the public announcement that at least one of the children A and B is dirty, they still do not know that they are dirty'. Moreover:

[math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{N},s\models[p\vee q!][(\neg K_Ap\land \neg K_A\neg p)\land (\neg K_B q \land\neg K_B\neg q)!](K_A p\land K_B q) }[/math]

'After the successive public announcements that at least one of the children A and B is dirty and that they still do not know whether they are dirty, A and B then both know that they are dirty'.

In this last statement, we see at work an interesting feature of the update process: a formula is not necessarily true after being announced. That is what we technically call “self-persistence” and this problem arises for epistemic formulas (unlike propositional formulas). One must not confuse the announcement and the update induced by this announcement, which might cancel some of the information encoded in the announcement.[27]

Arbitrary Events

In this section, we assume that events are not necessarily public and we focus on items 2 and 3 above, namely on how to represent events and on how to update an epistemic model with such a representation of events by means of a product update.

Event Model

Epistemic models are used to model how agents perceive the actual world. Their perception can also be described in terms of knowledge and beliefs about the world and about the other agents’ beliefs. The insight of the DEL approach is that one can describe how an event is perceived by the agents in a very similar way. Indeed, the agents’ perception of an event can also be described in terms of knowledge and beliefs. For example, the private announcement of [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] that her card is red can also be described in terms of knowledge and beliefs: while [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] tells [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] that her card is red (event [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math]) [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] believes that nothing happens (event [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math]). This leads to define the notion of event model whose definition is very similar to that of an epistemic model.

A pointed event model [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{E},e) }[/math] represents how the actual event represented by [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] is perceived by the agents. Intuitively, [math]\displaystyle{ f\in R_j(e) }[/math] means that while the possible event represented by [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] is occurring, agent [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math] considers possible that the possible event represented by [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is actually occurring.

An event model is a tuple [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E}=(W^\alpha,R_1^{\alpha},\ldots,R_m^{\alpha},I^{\alpha}) }[/math] where:

- [math]\displaystyle{ W^\alpha }[/math] is a non-empty set of possible events,

- [math]\displaystyle{ R_j^{\alpha}\subseteq W^\alpha\times W^\alpha }[/math] is a binary relation called an accessibility relation on [math]\displaystyle{ W^\alpha }[/math], for each [math]\displaystyle{ j\in AGTS }[/math],

- [math]\displaystyle{ I^{\alpha}:W^{\alpha}\rightarrow \mathcal{L}_{\textsf{EL}} }[/math] is a function called the precondition function assigning to each possible event a formula of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{L}_{\textsf{EL}} }[/math].

[math]\displaystyle{ R_j^{\alpha}(e) }[/math] denotes the set [math]\displaystyle{ \{f\in W^{\alpha}; (e,f)\in R_j^{\alpha} \} }[/math] .We write [math]\displaystyle{ e\in \mathcal{E} }[/math] for [math]\displaystyle{ e\in W^\alpha }[/math], and [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{E},e) }[/math] is called a pointed event model ([math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] often represents the actual event).

Card Example:

Let us resume the card example and assume that players [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] show their card to each other. As it turns out, [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] noticed that [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] showed her card to [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] but did not notice that [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] did so to [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math]. Players [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] know this. This event is represented below in the event model [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{E},e) }[/math].

The possible event [math]\displaystyle{ e }[/math] corresponds to the actual event ‘players [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] show their and cards respectively to each other’ (with precondition [math]\displaystyle{ {\color{red}{A}}\land {\color{green}{B}} }[/math]), [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] stands for the event ‘player [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] shows her green card’ (with precondition [math]\displaystyle{ {\color{green}{A}} }[/math]) and [math]\displaystyle{ g }[/math] stands for the atomic event ‘player [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] shows her red card’ (with precondition [math]\displaystyle{ {\color{red}{A}} }[/math]). Players [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] show their cards to each other, players [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] know this and consider it possible, while player [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] considers possible that player [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] shows her red card and also considers possible that player [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] shows her green card, since he does not know her card. In fact, that is all that player [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] considers possible because she did not notice that [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] showed her card.

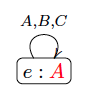

Another example of event model is given below. This second example corresponds to the event whereby Player [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] shows her red card publicly to everybody. Player [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] shows her red card, players [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] ‘know’ it, players [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] ‘know’ that each of them ‘knows’ it, etc. In other words, there is common knowledge among players [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] that player [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] shows her red card.

Product Update

The DEL product update is defined below.[5] This update yields a new pointed epistemic model [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{M},w)\otimes (\mathcal{E},e) }[/math] representing how the new situation which was previously represented by [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{M},w) }[/math] is perceived by the agents after the occurrence of the event represented by [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{E},e) }[/math].

Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M}=(W,R_1,\ldots,R_n,I) }[/math] be an epistemic model and let [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E}=(W^{\alpha},R_1^{\alpha},\ldots,R_n^{\alpha},I^{\alpha}) }[/math] be an event model. The product update of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E} }[/math] is the epistemic model [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M}\otimes\mathcal \mathcal{E}=(W^\otimes,R^\otimes_1,\ldots,R^{\otimes}_n,I^\otimes) }[/math] defined as follows: for all [math]\displaystyle{ v\in W }[/math] and all [math]\displaystyle{ f\in W^\alpha }[/math],

| [math]\displaystyle{ W^\otimes }[/math] | = | [math]\displaystyle{ \{(v,f)\in W\times W^\alpha; \mathcal{M},v\models I^{\alpha}(f)\} }[/math] |

| [math]\displaystyle{ R_j^\otimes(v,f) }[/math] | = | [math]\displaystyle{ \{(u,g)\in W^\otimes; u\in R_j(v)\textrm{~and~}g\in R^{\alpha}_j(f)\} }[/math] |

| [math]\displaystyle{ I^\otimes(v,f) }[/math] | = | [math]\displaystyle{ I(v) }[/math] |

If [math]\displaystyle{ w\in W }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ e\in W^{\alpha} }[/math] are such that [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{M},w\models I^{\alpha}(e) }[/math] then [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{M},w)\otimes(\mathcal{E},e) }[/math] denotes the pointed epistemic model [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{M}\otimes\mathcal{E},(w,e)) }[/math]. This definition of the product update is conceptually grounded.[6]

Card Example:

As a result of the first event described above (Players [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] show their cards to each other in front of player [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math]), the agents update their beliefs. We get the situation represented in the pointed epistemic model [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{M},w)\otimes(\mathcal{E},e) }[/math] below. In this pointed epistemic model, the following statement holds: [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{M},w)\otimes(\mathcal{E},e)\models ({\color{green}{B}}\land K_{A} {\color{green}{B}}) \land K_{C}\neg K_{A} {\color{green}{B}}. }[/math] It states that player [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] knows that player [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] has the card but player [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] 'believes' that it is not the case.

The result of the second event is represented below. In this pointed epistemic model, the following statement holds: [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathcal{M},w)\otimes(\mathcal{F},e)\models C_{\{B,C\}}({\color{red}{A}}\land{\color{green}{B}}\land{\color{blue}{C}})\land \neg K_A({\color{green}{B}}\land{\color{blue}{C}}) }[/math]. It states that there is common knowledge among [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] that they know the true state of the world (namely [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] has the red card, [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] has the green card and [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] has the blue card), but [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] does not know it.

Based on these three components (epistemic model, event model and product update), Baltag, Moss and Solecki defined a general logical language inspired from the logical language of propositional dynamic logic[25] to reason about information and knowledge change.[5][6]

See also

- Epistemic logic

- Epistemology

- Logic in computer science

- Modal logic

Notes

- ↑ Plaza, Jan (2007-07-26). "Logics of public communications". Synthese 158 (2): 165–179. doi:10.1007/s11229-007-9168-7. ISSN 0039-7857.

- ↑ Gerbrandy, Jelle; Groeneveld, Willem (1997-04-01). "Reasoning about Information Change". Journal of Logic, Language and Information 6 (2): 147–169. doi:10.1023/A:1008222603071. ISSN 0925-8531.

- ↑ Veltman, Frank (1996-06-01). "Defaults in update semantics". Journal of Philosophical Logic 25 (3): 221–261. doi:10.1007/BF00248150. ISSN 0022-3611.

- ↑ Ditmarsch, Hans P. van (2002-06-01). "Descriptions of Game Actions". Journal of Logic, Language and Information 11 (3): 349–365. doi:10.1023/A:1015590229647. ISSN 0925-8531.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Alexandru Baltag; Lawrence S. Moss; Slawomir Solecki (1998). "The Logic of Public Announcements and Common Knowledge and Private Suspicions". Theoretical Aspects of Rationality and Knowledge (TARK).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Baltag, Alexandru; Moss, Lawrence S. (2004-03-01). "Logics for Epistemic Programs". Synthese 139 (2): 165–224. doi:10.1023/B:SYNT.0000024912.56773.5e. ISSN 0039-7857.

- ↑ A distinction is sometimes made between events and actions, an action being a specific type of event performed by an agent.

- ↑ Boh, Ivan (1993). Epistemic Logic in the later Middle Ages. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415057264.

- ↑ Jaako, Hintikka (1962). Knowledge and Belief, An Introduction to the Logic of the Two Notions. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1904987086.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Lenzen, Wolfgang (1978). "Recent Work in Epistemic Logic". Acta Philosophica Fennica.

- ↑ Battigalli, Pierpaolo; Bonanno, Giacomo (1999-06-01). "Recent results on belief, knowledge and the epistemic foundations of game theory". Research in Economics 53 (2): 149–225. doi:10.1006/reec.1999.0187. http://repec.dss.ucdavis.edu/files/rfM2rUmEkFZMsfwVAGgXj8TM/98-14.pdf.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Ronald Fagin; Joseph Halpern; Yoram Moses; Moshe Vardi (1995). Reasoning about Knowledge. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262562003.

- ↑ Lewis, David (1969). Convention, a Philosophical Study. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674170254.

- ↑ Aumann, Robert J. (1976-11-01). "Agreeing to Disagree". The Annals of Statistics 4 (6): 1236–1239. doi:10.1214/aos/1176343654.

- ↑ Patrick Blackburn; Maarten de Rijke; Yde Venema (2001). Modal Logic. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521527149.

- ↑ "Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy » KK Principle (Knowing that One Knows) Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy » Print". http://www.iep.utm.edu/kk-princ/print/.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 For example, assume that a university professor believes (is certain) that one of her colleague’s seminars is on Thursday (formally [math]\displaystyle{ B p }[/math]). She is actually wrong because it is on Tuesday ([math]\displaystyle{ \neg p }[/math]). Therefore, she does not know that her colleague’s seminar is on Tuesday ([math]\displaystyle{ \neg K p }[/math]). If we assume that axiom is valid then we should conclude that she knows that she does not know that her colleague’s seminar is on Tuesday ([math]\displaystyle{ K \neg K p }[/math]) (and therefore she also believes that she does not know it: [math]\displaystyle{ B\neg K p }[/math]). This is obviously counterintuitive.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Lenzen, Wolfgang (1979-03-01). "Epistemologische betrachtungen zu [S4, S5]" (in de). Erkenntnis 14 (1): 33–56. doi:10.1007/BF00205012. ISSN 0165-0106.

- ↑ Aucher, Guillaume (2015-03-18). "Intricate Axioms as Interaction Axioms". Studia Logica 103 (5): 1035–1062. doi:10.1007/s11225-015-9609-0. ISSN 0039-3215. https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01193284/file/FinalRevisedStudiaLogica2014.pdf.

- ↑ Stalnaker, Robert (2006-03-01). "On Logics of Knowledge and Belief". Philosophical Studies 128 (1): 169–199. doi:10.1007/s11098-005-4062-y. ISSN 0031-8116.

- ↑ Floridi, Luciano (2011-01-27). "The logic of being informed". The Philosophy of Information. Oxford University Press. pp. 224–243. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199232383.003.0010. ISBN 9780191594809. http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199232383.001.0001/acprof-9780199232383-chapter-10.

- ↑ Halpern, Joseph Y.; Moses, Yoram (1992). "A guide to completeness and complexity for modal logics of knowledge and belief". Artificial Intelligence 54 (3): 319–379. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(92)90049-4.

- ↑ Halpern, Joseph Y. (1995-06-01). "The effect of bounding the number of primitive propositions and the depth of nesting on the complexity of modal logic". Artificial Intelligence 75 (2): 361–372. doi:10.1016/0004-3702(95)00018-A.

- ↑ van Ditmarsch, Hans; Kooi, Barteld (2015). One Hundred Prisoners and a Light Bulb - Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-16694-0. ISBN 978-3-319-16693-3.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 David Harel; Dexter Kozen; Jerzy Tiuryn (2000). Dynamic Logic. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262082891. https://archive.org/details/dynamiclogicfoun00davi_0.

- ↑ Lutz, Carsten (2006-01-01). "Complexity and succinctness of public announcement logic". Proceedings of the fifth international joint conference on Autonomous agents and multiagent systems. AAMAS '06. New York, NY, USA: ACM. pp. 137–143. doi:10.1145/1160633.1160657. ISBN 978-1-59593-303-4. https://tud.qucosa.de/api/qucosa%3A79335/attachment/ATT-0/.

- ↑ Ditmarsch, Hans Van; Kooi, Barteld (2006-07-01). "The Secret of My Success". Synthese 151 (2): 201–232. doi:10.1007/s11229-005-3384-9. ISSN 0039-7857.

References

- van Benthem, Johan (2011). Logical Dynamics of Information and Interaction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521873970.

- Hans, van Ditmarsch; Halpern, Joseph; van der Hoek, Wiebe; Kooi, Barteld (2015). Handbook of Epistemic Logic. London: College publication. ISBN 978-1848901582.

- van Ditmarsch, Hans, van der Hoek, Wiebe, and Kooi, Barteld (2007). Dynamic Epistemic Logic. Ithaca: volume 337 of Synthese library. Springer.. ISBN 978-1-4020-5839-4.

- Fagin, Ronald; Halpern, Joseph; Moses, Yoram; Vardi, Moshe (2003). Reasoning about Knowledge. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-56200-3. A classic reference.

- Hintikka, Jaakko (1962). Knowledge and Belief - An Introduction to the Logic of the Two Notions. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-904987-08-6. https://archive.org/details/knowledgebeliefi00hint_0..

External links

- Baltag, Alexandru; Renne, Bryan. "Dynamic Epistemic Logic". in Zalta, Edward N.. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/dynamic-epistemic/.

- van Ditmarsch, Hans; van der Hoek, Wiebe; Kooi, Barteld. "Dynamic Epistemic Logic". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. http://www.iep.utm.edu/de-logic.

- Hendricks, Vincent; Symons, John. "Epistemic Logic". in Zalta, Edward N.. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logic-epistemic/.

- Garson, James. "Modal logic". in Zalta, Edward N.. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/logic-modal/.

|