Privilege escalation

Privilege escalation is the act of exploiting a bug, a design flaw, or a configuration oversight in an operating system or software application to gain elevated access to resources that are normally protected from an application or user. The result is that an application with more privileges than intended by the application developer or system administrator can perform unauthorized actions.

Background

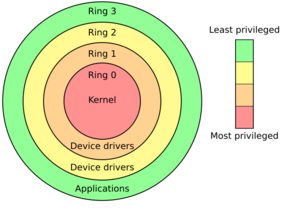

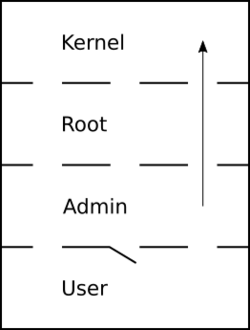

Most computer systems are designed for use with multiple user accounts, each of which has abilities known as privileges. Common privileges include viewing and editing files or modifying system files.

Privilege escalation means users receive privileges they are not entitled to. These privileges can be used to delete files, view private information, or install unwanted programs such as viruses. It usually occurs when a system has a bug that allows security to be bypassed or, alternatively, has flawed design assumptions about how it will be used. Privilege escalation occurs in two forms:

- Vertical privilege escalation, also known as privilege elevation, where a lower privilege user or application accesses functions or content reserved for higher privilege users or applications (e.g. Internet Banking users can access site administrative functions or the password for a smartphone can be bypassed.)

- Horizontal privilege escalation, where a normal user accesses functions or content reserved for other normal users (e.g. Internet Banking User A accesses the Internet bank account of User B)

Vertical

This type of privilege escalation occurs when the user or process is able to obtain a higher level of access than an administrator or system developer intended, possibly by performing kernel-level operations.

Examples

In some cases, a high-privilege application assumes that it would only be provided with input matching its interface specification, thus doesn't validate this input. Then, an attacker may be able to exploit this assumption, in order to run unauthorized code with the application's privileges:

- Some Windows services are configured to run under the Local System user account. A vulnerability such as a buffer overflow may be used to execute arbitrary code with privilege elevated to Local System. Alternatively, a system service that is impersonating a lesser user can elevate that user's privileges if errors are not handled correctly while the user is being impersonated (e.g. if the user has introduced a malicious error handler)

- Under some legacy versions of the Microsoft Windows operating system, the All Users screensaver runs under the Local System account – any account that can replace the current screensaver binary in the file system or Registry can therefore elevate privileges.

- In certain versions of the Linux kernel it was possible to write a program that would set its current directory to

/etc/cron.d, request that a core dump be performed in case it crashes and then have itself killed by another process. The core dump file would have been placed at the program's current directory, that is,/etc/cron.d, andcronwould have treated it as a text file instructing it to run programs on schedule. Because the contents of the file would be under attacker's control, the attacker would be able to execute any program with root privileges. - Cross Zone Scripting is a type of privilege escalation attack in which a website subverts the security model of web browsers, thus allowing it to run malicious code on client computers.

- There are also situations where an application can use other high privilege services and has incorrect assumptions about how a client could manipulate its use of these services. An application that can execute Command line or shell commands could have a Shell Injection vulnerability if it uses unvalidated input as part of an executed command. An attacker would then be able to run system commands using the application's privileges.

- Texas Instruments calculators (particularly the TI-85 and TI-82) were originally designed to use only interpreted programs written in dialects of TI-BASIC; however, after users discovered bugs that could be exploited to allow native Z-80 code to run on the calculator hardware, TI released programming data to support third-party development. (This did not carry on to the ARM-based TI-Nspire, for which jailbreaks using Ndless have been found but are still actively fought against by Texas Instruments.)

- Some versions of the iPhone allow an unauthorised user to access the phone while it is locked.[1]

Jailbreaking

In computer security, jailbreaking is defined as the act of removing limitations that a vendor attempted to hard-code into its software or services.[2] A common example is the use of toolsets to break out of a chroot or jail in UNIX-like operating systems[3] or bypassing digital rights management (DRM). In the former case, it allows the user to see files outside of the filesystem that the administrator intends to make available to the application or user in question. In the context of DRM, this allows the user to run arbitrarily defined code on devices with DRM as well as break out of chroot-like restrictions. The term originated with the iPhone/iOS jailbreaking community and has also been used as a term for PlayStation Portable hacking; these devices have repeatedly been subject to jailbreaks, allowing the execution of arbitrary code, and sometimes have had those jailbreaks disabled by vendor updates.

iOS systems including the iPhone, iPad, and iPod Touch have been subject to iOS jailbreaking efforts since they were released, and continuing with each firmware update.[4][5] iOS jailbreaking tools include the option to install package frontends such as Cydia and Installer.app, third-party alternatives to the App Store, as a way to find and install system tweaks and binaries. To prevent iOS jailbreaking, Apple has made the device boot ROM execute checks for SHSH blobs in order to disallow uploads of custom kernels and prevent software downgrades to earlier, jailbreakable firmware. In an "untethered" jailbreak, the iBoot environment is changed to execute a boot ROM exploit and allow submission of a patched low level bootloader or hack the kernel to submit the jailbroken kernel after the SHSH check.

A similar method of jailbreaking exists for S60 Platform smartphones, where utilities such as HelloOX allow the execution of unsigned code and full access to system files.[6][7] or edited firmware (similar to the M33 hacked firmware used for the PlayStation Portable)[8] to circumvent restrictions on unsigned code. Nokia has since issued updates to curb unauthorized jailbreaking, in a manner similar to Apple.

In the case of gaming consoles, jailbreaking is often used to execute homebrew games. In 2011, Sony, with assistance from law firm Kilpatrick Stockton, sued 21-year-old George Hotz and associates of the group fail0verflow for jailbreaking the PlayStation 3 (see Sony Computer Entertainment America v. George Hotz and PlayStation Jailbreak).

Jailbreaking can also occur in systems and software that use generative artificial intelligence models, such as ChatGPT. In jailbreaking attacks on artificial intelligence systems, users are able to manipulate the model to behave differently than it was programmed, making it possible to reveal information about how the model was instructed and induce it to respond in an anomalous or harmful way.[9][10]

Android

Android phones can be officially rooted by either going through manufacturers controlled process, using an exploit to gain root, or flashing custom recovery. Manufacturers allow rooting through a process they control, while some allow the phone to be rooted simply by pressing specific key combinations at boot time, or by other self-administered methods. Using a manufacturers method almost always factory resets the device, making rooting useless to people who want to view the data, and also voids the warranty permanently, even if the device is derooted and reflashed. Software exploits commonly either target a root-level process that is accessible to the user, by using an exploit specific to the phone's kernel, or using a known Android exploit that has been patched in newer versions; by not upgrading the phone, or intentionally downgrading the version.

Mitigation strategies

Operating systems and users can use the following strategies to reduce the risk of privilege escalation:

- Data Execution Prevention

- Address space layout randomization (to make it harder for buffer overruns to execute privileged instructions at known addresses in memory)

- Running applications with least privilege (for example by running Internet Explorer with the Administrator SID disabled in the process token) in order to reduce the ability of buffer overrun exploits to abuse the privileges of an elevated user.

- Requiring kernel mode code to be digitally signed.

- Patching

- Use of compilers that trap buffer overruns[11]

- Encryption of software and/or firmware components.

- Use of an operating system with Mandatory Access Controls (MAC) such as SELinux[12]

- Kernel Data Relocation Mechanism (dynamically relocates privilege information in the running kernel, preventing privilege escalation attacks using memory corruption)

Recent research has shown what can effectively provide protection against privilege escalation attacks. These include the proposal of the additional kernel observer (AKO), which specifically prevents attacks focused on OS vulnerabilities. Research shows that AKO is in fact effective against privilege escalation attacks.[13]

Horizontal

Horizontal privilege escalation occurs when an application allows the attacker to gain access to resources which normally would have been protected from an application or user. The result is that the application performs actions with the same user but different security context than intended by the application developer or system administrator; this is effectively a limited form of privilege escalation (specifically, the unauthorized assumption of the capability of impersonating other users). Compared to the vertical privilege escalation, horizontal requires no upgrading the privilege of accounts. It often relies on the bugs in the system.[14]

Examples

This problem often occurs in web applications. Consider the following example:

- User A has access to their own bank account in an Internet Banking application.

- User B has access to their own bank account in the same Internet Banking application.

- The vulnerability occurs when User A is able to access User B's bank account by performing some sort of malicious activity.

This malicious activity may be possible due to common web application weaknesses or vulnerabilities.

Potential web application vulnerabilities or situations that may lead to this condition include:

- Predictable session IDs in the user's HTTP cookie

- Session fixation

- Cross-site scripting

- Easily guessable passwords

- Theft or hijacking of session cookies

- Keystroke logging

See also

- Cybersecurity

- Defensive programming

- Hacking of consumer electronics

- Illegal number

- Principle of least privilege

- Privilege revocation (computing)

- Privilege separation

- Rooting (Android OS)

- Row hammer

References

- ↑ Taimur Asad (October 27, 2010). "Apple Acknowledges iOS 4.1 Security Flaw. Will Fix it in November with iOS 4.2". RedmondPie. http://www.redmondpie.com/ios-4.2-to-fix-ios-4.1-lockscreen-security-flaw/.

- ↑ "Definition of JAILBREAK" (in en). https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/jailbreak.

- ↑ Cyrus Peikari; Anton Chuvakin (2004). Security Warrior: Know Your Enemy. "O'Reilly Media, Inc.". p. 304. ISBN 978-0-596-55239-8. https://archive.org/details/securitywarrior0000peik.

- ↑ James Quintana Pearce (2007-09-27), Apple's Disagreement With Orange, IPhone Hackers, paidContent.org, http://paidcontent.org/article/419-apples-disagreement-with-orange-iphone-hackers/, retrieved 2011-11-25

- ↑ "Reports: Next iPhone update will break third-party apps, bust unlocks"]. http://www.computerworld.com/action/article.do?command=viewArticleBasic&taxonomyId=11&articleId=9054719&intsrc=hm_topic.

- ↑ Phat^Trance (Feb 16, 2010). "Announcement: Forum down for maintaining". http://dailymobile.se/forum/index.php?topic=1165.0. "Just wanted to let you guys know that the forum is down for maintaining. It will be back online in a day or so (i kinda messed up the config files and need to restore one day old backup, so i thought why not update the entire server platform)"

- ↑ "HelloOX 1.03: one step hack for Symbian S60 3rd ed. phones, and for Nokia 5800 XpressMusic too". http://symbianism.blogspot.com/2009/02/helloox-103-one-step-hack-for-symbian.html.

- ↑ "Bypass Symbian Signed & Install UnSigned SISX/J2ME Midlets on Nokia S60 v3 with Full System Permissions". http://thinkabdul.com/2007/10/29/tutorial-bypass-symbian-signed-install-unsigned-sisxj2me-midlets-on-nokia-s60-v3-with-full-system-permissions/.

- ↑ "What is Jailbreaking in A.I. models like ChatGPT?". https://www.techopedia.com/what-is-jailbreaking-in-ai-models-like-chatgpt.

- ↑ "ChatGPT’s ‘jailbreak’ tries to make the A.I. break its own rules, or die". https://www.cnbc.com/2023/02/06/chatgpt-jailbreak-forces-it-to-break-its-own-rules.html.

- ↑ "Microsoft Minimizes Threat of Buffer Overruns, Builds Trustworthy Applications". Microsoft. September 2005. http://download.microsoft.com/documents/customerevidence/12374_Microsoft_GS_Switch_CS_final.doc.[|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ Smalley, Stephen. "Laying a Secure Foundation for Mobile Devices". http://www.internetsociety.org/sites/default/files/Presentation_Smalley.pdf.

- ↑ Yamauchi, Toshihiro; Akao, Yohei; Yoshitani, Ryota; Nakamura, Yuichi; Hashimoto, Masaki (August 2021). "Additional kernel observer: privilege escalation attack prevention mechanism focusing on system call privilege changes" (in en). International Journal of Information Security 20 (4): 461–473. doi:10.1007/s10207-020-00514-7. ISSN 1615-5262. https://link.springer.com/10.1007/s10207-020-00514-7.

- ↑ Diogenes, Yuri (2019). Cybersecurity - Attack and Defense Strategies - Second Edition. Erdal Ozkaya, Safari Books Online (2nd ed.). pp. 304. ISBN 978-1-83882-779-3. OCLC 1139764053. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1139764053.

| This article is part of a series on |

| Information security |

|---|

| Related security categories |

| Threats |

| Defenses |

|