Qualitative research

Qualitative research is a type of research that aims to gather and analyse non-numerical (descriptive) data in order to gain an understanding of individuals' social reality, including understanding their attitudes, beliefs, and motivation. This type of research typically involves in-depth interviews, focus groups, or observations in order to collect data that is rich in detail and context. Qualitative research is often used to explore complex phenomena or to gain insight into people's experiences and perspectives on a particular topic. It is particularly useful when researchers want to understand the meaning that people attach to their experiences or when they want to uncover the underlying reasons for people's behavior. Qualitative methods include ethnography, grounded theory, discourse analysis, and interpretative phenomenological analysis.[1] Qualitative research methods have been used in sociology, anthropology, political science, psychology, communication studies, social work, folklore, educational research, information science and software engineering research.[2][3][4][5]

Background

Qualitative research has been informed by several strands of philosophical thought and examines aspects of human life, including culture, expression, beliefs, morality, life stress, and imagination.[6] Contemporary qualitative research has been influenced by a number of branches of philosophy, for example, positivism, postpositivism, critical theory, and constructivism.[7] The historical transitions or 'moments' in qualitative research, together with the notion of 'paradigms' (Denzin & Lincoln, 2005), have received widespread popularity over the past decades. However, some scholars have argued that the adoptions of paradigms may be counterproductive and lead to less philosophically engaged communities. In this regard, Pernecky[8] proposed an alternative way to implementing philosophical concerns in qualitative inquiry so that researchers are able to maintain the needed intellectual mobility and elasticity.

Approaches to inquiry

The use of nonquantitative material as empirical data has been growing in many areas of the social sciences, including learning sciences, development psychology and cultural psychology.[9] Several philosophical and psychological traditions have influenced investigators' approaches to qualitative research, including phenomenology, social constructionism, symbolic interactionism, and positivism.[10][11]

Philosophical traditions

Phenomenology refers to the philosophical study of the structure of an individual's consciousness and general subjective experience. Approaches to qualitative research based on constructionism, such as grounded theory, pay attention to how the subjectivity of both the researcher and the study participants can affect the theory that develops out of the research. The symbolic interactionist approach to qualitative research examines how individuals and groups develop an understanding of the world. Traditional positivist approaches to qualitative research seek a more objective understanding of the social world. Qualitative researchers have also been influenced by the sociology of knowledge and the work of Alfred Schütz, Peter L. Berger, Thomas Luckmann, and Harold Garfinkel.

More recent philosophical contributions to qualitative inquiry (Pernecky, 2016[8]) have covered topics such as scepticism, idea-ism, idealism, hermeneutics, empiricism and rationalism, and introduced the qualitative community to a variety of realist approaches that are available within the wide philosophical spectrum of qualitative thought. Pernecky also deals with some of the neglected domains in qualitative research, such as social ontology, and ventures into new territories (e.g., quantum mechanics) in order to stimulate a more contemporary debate about common qualitative problems, such as absolutism and universalism.

Sources of data

Qualitative researchers use different sources of data to understand the topic they are studying. These data sources include interview transcripts, videos of social interactions, notes, verbal reports[9] and artifacts such as books or works of art. The case study method exemplifies qualitative researchers' preference for depth, detail, and context.[12][13] Data triangulation is also a strategy used in qualitative research.[14] Autoethnography, the study of self, is a qualitative research method in which the researcher uses his or her personal experience to understand an issue.

Grounded theory is an inductive type of research, based on ("grounded" in) a very close look at the empirical observations a study yields.[15][16] Thematic analysis involves analyzing patterns of meaning. Conversation analysis is primarily used to analyze spoken conversations. Biographical research is concerned with the reconstruction of life histories, based on biographical narratives and documents. Narrative inquiry studies the narratives that people use to describe their experience.

Data collection

Qualitative researchers may gather information through observations, note-taking, interviews, focus groups (group interviews), documents, images and artifacts.[17][18][19][20][21][22][23]

Interviews

Research interviews are an important method of data collection in qualitative research. An interviewer is usually a professional or paid researcher, sometimes trained, who poses questions to the interviewee, in an alternating series of usually brief questions and answers, to elicit information. Compared to something like a written survey, qualitative interviews allow for a significantly higher degree of intimacy,[24] with participants often revealing personal information to their interviewers in a real-time, face-to-face setting. As such, this technique can evoke an array of significant feelings and experiences within those being interviewed. Sociologists Bredal, Stefansen and Bjørnholt identified three "participant orientations", that they described as "telling for oneself", "telling for others" and "telling for the researcher". They also proposed that these orientations implied "different ethical contracts between the participant and researcher".[25]

Participant observation

In participant observation[26] ethnographers get to understand a culture by directly participating in the activities of the culture they study.[27] Participant observation extends further than ethnography and into other fields, including psychology. For example, by training to be an EMT and becoming a participant observer in the lives of EMTs, Palmer studied how EMTs cope with the stress associated with some of the gruesome emergencies they deal with.[28]

Recursivity

In qualitative research, the idea of recursivity refers to the emergent nature of research design. In contrast to standardized research methods, recursivity embodies the idea that the qualitative researcher can change a study's design during the data collection phase.[13]

Recursivity in qualitative research procedures contrasts to the methods used by scientists who conduct experiments. From the perspective of the scientist, data collection, data analysis, discussion of the data in the context of the research literature, and drawing conclusions should be each undertaken once (or at most a small number of times). In qualitative research however, data are collected repeatedly until one or more specific stopping conditions are met, reflecting a nonstatic attitude to the planning and design of research activities. An example of this dynamism might be when the qualitative researcher unexpectedly changes their research focus or design midway through a study, based on their first interim data analysis. The researcher can even make further unplanned changes based on another interim data analysis. Such an approach would not be permitted in an experiment. Qualitative researchers would argue that recursivity in developing the relevant evidence enables the researcher to be more open to unexpected results and emerging new constructs.[13]

Data analysis

Qualitative researchers have a number of analytic strategies available to them.[29][30][31]

Coding

In general, coding refers to the act of associating meaningful ideas with the data of interest. In the context of qualitative research, interpretative aspects of the coding process are often explicitly recognized and articulated; coding helps to produce specific words or short phrases believed to be useful abstractions from the data.[32][33]

Pattern thematic analysis

Data may be sorted into patterns for thematic analyses as the primary basis for organizing and reporting the study findings.[34]

Content analysis

According to Krippendorf,[35] "[c]ontent analysis is a research technique for making replicable and valid inference from data to their context" (p. 21). It is applied to documents and written and oral communication. Content analysis is an important building block in the conceptual analysis of qualitative data. It is frequently used in sociology. For example, content analysis has been applied to research on such diverse aspects of human life as changes in perceptions of race over time,[36] the lifestyles of contractors,[37] and even reviews of automobiles.[38]

Issues

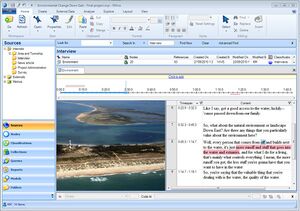

Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS)

Contemporary qualitative data analyses can be supported by computer programs (termed computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software).[39] These programs have been employed with or without detailed hand coding or labeling. Such programs do not supplant the interpretive nature of coding. The programs are aimed at enhancing analysts' efficiency at applying, retrieving, and storing the codes generated from reading the data. Many programs enhance efficiency in editing and revising codes, which allow for more effective work sharing, peer review, data examination, and analysis of large datasets.[39]

Common qualitative data analysis software includes:

A criticism of quantitative coding approaches is that such coding sorts qualitative data into predefined (nomothetic) categories that are reflective of the categories found in objective science. The variety, richness, and individual characteristics of the qualitative data are reduced or, even, lost.[citation needed]

To defend against the criticism that qualitative approaches to data are too subjective, qualitative researchers assert that by clearly articulating their definitions of the codes they use and linking those codes to the underlying data, they preserve some of the richness that might be lost if the results of their research boiled down to a list of predefined categories. Qualitative researchers also assert that their procedures are repeatable, which is an idea that is valued by quantitatively oriented researchers.[citation needed]

Sometimes researchers rely on computers and their software to scan and reduce large amounts of qualitative data. At their most basic level, numerical coding schemes rely on counting words and phrases within a dataset; other techniques involve the analysis of phrases and exchanges in analyses of conversations. A computerized approach to data analysis can be used to aid content analysis, especially when there is a large corpus to unpack.

Trustworthiness

A central issue in qualitative research is trustworthiness (also known as credibility or, in quantitative studies, validity).[40] There are many ways of establishing trustworthiness, including member check, interviewer corroboration, peer debriefing, prolonged engagement, negative case analysis, auditability, confirmability, bracketing, and balance.[40] Data triangulation and eliciting examples of interviewee accounts are two of the most commonly used methods of establishing the trustworthiness of qualitative studies.[41] Transferability of results has also been considered as an indicator of validity.[42]

Limitations of qualitative research

Qualitative research is not without limitations. These limitations include participant reactivity, the potential for a qualitative investigator to over-identify with one or more study participants, "the impracticality of the Glaser-Strauss idea that hypotheses arise from data unsullied by prior expectations," the inadequacy of qualitative research for testing cause-effect hypotheses, and the Baconian character of qualitative research.[43] Participant reactivity refers to the fact that people often behave differently when they know they are being observed. Over-identifying with participants refers to a sympathetic investigator studying a group of people and ascribing, more than is warranted, a virtue or some other characteristic to one or more participants. Compared to qualitative research, experimental research and certain types of nonexperimental research (e.g., prospective studies), although not perfect, are better means for drawing cause-effect conclusions.

Glaser and Strauss,[15] influential members of the qualitative research community, pioneered the idea that theoretically important categories and hypotheses can emerge "naturally" from the observations a qualitative researcher collects, provided that the researcher is not guided by preconceptions. The ethologist David Katz wrote "a hungry animal divides the environment into edible and inedible things....Generally speaking, objects change...according to the needs of the animal."[44] Karl Popper carrying forward Katz's point wrote that "objects can be classified and can become similar or dissimilar, only in this way--by being related to needs and interests. This rule applied not only to animals but also to scientists."[45] Popper made clear that observation is always selective, based on past research and the investigators' goals and motives and that preconceptionless research is impossible.

The Baconian character of qualitative research refers to the idea that a qualitative researcher can collect enough observations such that categories and hypotheses will emerge from the data. Glaser and Strauss developed the idea of theoretical sampling by way of collecting observations until theoretical saturation is obtained and no additional observations are required to understand the character of the individuals under study.[15] Bertrand Russell suggested that there can be no orderly arrangement of observations such that a hypothesis will jump out of those ordered observations; some provisional hypothesis usually guides the collection of observations.[46]

In psychology

Community psychology

Autobiographical narrative research has been conducted in the field of community psychology.[6] A selection of autobiographical narratives of community psychologists can be found in the book Six Community Psychologists Tell Their Stories: History, Contexts, and Narrative.[47]

Educational psychology

Edwin Farrell used qualitative methods to understand the social reality of at-risk high school students.[48] Later he used similar methods to understand the reality of successful high school students who came from the same neighborhoods as the at-risk students he wrote about in his previously mentioned book.[49]

Health psychology

In the field of health psychology, qualitative methods have become increasingly employed in research on understanding health and illness and how health and illness are socially constructed in everyday life.[50][51] Since then, a broad range of qualitative methods have been adopted by health psychologists, including discourse analysis, thematic analysis, narrative analysis, and interpretative phenomenological analysis. In 2015, the journal Health Psychology published a special issue on qualitative research.[52]

Industrial and organizational psychology

According to Doldor and colleagues[53] organizational psychologists extensively use qualitative research "during the design and implementation of activities like organizational change, training needs analyses, strategic reviews, and employee development plans."

Occupational health psychology

Although research in the field of occupational health psychology (OHP) has predominantly been quantitatively oriented, some OHP researchers[54][55] have employed qualitative methods. Qualitative research efforts, if directed properly, can provide advantages for quantitatively oriented OHP researchers. These advantages include help with (1) theory and hypothesis development, (2) item creation for surveys and interviews, (3) the discovery of stressors and coping strategies not previously identified, (4) interpreting difficult-to-interpret quantitative findings, (5) understanding why some stress-reduction interventions fail and others succeed, and (6) providing rich descriptions of the lived lives of people at work.[43][56] Some OHP investigators have united qualitative and quantitative methods within a single study (e.g., Elfering et al., [2005][57]); these investigators have used qualitative methods to assess job stressors that are difficult to ascertain using standard measures and well validated standardized instruments to assess coping behaviors and dependent variables such as mood.[43]

Social media psychology

Since the advent of social media in the early 2000s, formerly private accounts of personal experiences have become widely shared with the public by millions of people around the world. Disclosures are often made openly, which has contributed to social media's key role in movements like the #metoo movement.[58]

The abundance of self-disclosure on social media has presented an unprecedented opportunity for qualitative and mixed methods researchers; mental health problems can now be investigated qualitatively more widely, at a lower cost, and with no intervention by the researchers.[59] To take advantage of these data, researchers need to have mastered the tools for conducting qualitative research.[60]

Journals

- Qualitative Inquiry

- Qualitative Research

- The Qualitative Report

See also

- Computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS)

- Hermeneutics

- Methodological dualism

- Participatory action research – Approach to research in social sciences

- Process tracing

- Qualitative geography – Subfield of geographic methods

- Qualitative psychological research – Psychological research with qualitative methods

- Quantitative research – All procedures for the numerical representation of empirical facts

- Real world data

References

- ↑ Creswell, John W.. Educational research : planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. ISBN 1-299-95719-6. OCLC 859836343.

- ↑ King, Gary; Keohane, Robert O.; Verba, Sidney (2021-08-17) (in en). Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research, New Edition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-22464-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=RFMgEAAAQBAJ.

- ↑ "QUALITI". cardiff.ac.uk. http://www.cardiff.ac.uk/socsi/qualiti/PubSocMethJourn.html.

- ↑ Alasuutari, Pertti (2010). "The rise and relevance of qualitative research". International Journal of Social Research Methodology 13 (2): 139–55. doi:10.1080/13645570902966056.

- ↑ Seaman, Carolyn (1999). "Qualitative methods in empirical studies of software engineering". Transactions on Software Engineering 25 (4): 557–572. doi:10.1109/32.799955.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Wertz, Charmaz, McMullen. "Five Ways of Doing Qualitative Analysis: Phenomenological Psychology, Grounded Theory, Discourse Analysis, Narrative Research, and Intuitive Inquiry". 16-18. The Guilford Press: March 30, 2011. 1st ed. Print.

- ↑ Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). "Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging influences" In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (3rd ed.), pp. 191-215. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ISBN:0-7619-2757-3

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Pernecky, T. (2016). Epistemology and Metaphysics for Qualitative Research. London: SAGE Publications.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Packer, Martin (2010). The Science of Qualitative Research. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511779947. ISBN 9780521768870. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/science-of-qualitative-research/DF2D130955944017C256F6BDD0B74F11.

- ↑ Creswell, John (2006). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Sage.

- ↑ Creswell, John (2008). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Sage.

- ↑ Racino, J. (1999). Policy, Program Evaluation and Research in Disability: Community Support for All. London: Haworth Press. ISBN 978-0-7890-0597-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=qDavoDQiH-QC.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Given, L. M., ed (2008). The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods.. SAGE Publications.

- ↑ Teeter, Preston; Sandberg, Jorgen (2016). "Constraining or Enabling Green Capability Development? How Policy Uncertainty Affects Organizational Responses to Flexible Environmental Regulations". British Journal of Management 28 (4): 649–665. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12188. http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/93826/1/WRAP-constraining-enabling-green-policy-flexible-Sandberg-2017.pdf.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

- ↑ Ralph, N.; Birks, M.; Chapman, Y. (29 September 2014). "Contextual Positioning: Using Documents as Extant Data in Grounded Theory Research". SAGE Open 4 (3): 215824401455242. doi:10.1177/2158244014552425.

- ↑ Marshall, Catherine & Rossman, Gretchen B. (1998). Designing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. ISBN:0-7619-1340-8

- ↑ Bogdan, R.; Ksander, M. (1980). "Policy data as a social process: A qualitative approach to quantitative data". Human Organization 39 (4): 302–309. doi:10.17730/humo.39.4.x42432981487k54q.

- ↑ Rosenthal, Gabriele (2018). Social Interpretive Research. An Introduction.. Göttingen: Universitätsverlag Göttingen. doi:10.17875/gup2018-1103. ISBN 978-3-86395-374-4. https://univerlag.uni-goettingen.de/handle/3/isbn-978-3-86395-374-4.

- ↑ Savin-Baden, M.; Major, C. (2013). Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

- ↑ Taylor, S. J.; Bogdan, R. (1984). Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods: The Search for Meanings (2nd ed.). Singapore: John Wiley and Sons.

- ↑ Murphy, E; Dingwall, R (2003). Qualitative methods and health policy research (1st edition). Routledge (reprinted as an e-book in 2017).

- ↑ Babbie, Earl (2014). The Basics of Social Research (6th ed.). Belmont, California: Wadsworth Cengage. pp. 303–04. ISBN 9781133594147. OCLC 824081715.

- ↑ Seidman, Irving. Interviewing as Qualitative Research: A Guide for Researchers in Education and the Social Sciences. Teachers College Press, 1998, pg.49

- ↑ Bredal, Anja; Stefansen, Kari; Bjørnholt, Margunn (2022). "Why do people participate in research interviews? Participant orientations and ethical contracts in interviews with victims of interpersonal violence". Qualitative Research. doi:10.1177/14687941221138409.

- ↑ "Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector's Field Guide". techsociety.com. http://www.techsociety.com/cal/soc190/fssba2009/ParticipantObservation.pdf.

- ↑ Lindlof, T. R., & Taylor, B. C. (2002) Qualitative communication research methods: Second edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc. ISBN:0-7619-2493-0

- ↑ Palmer, C.E. (1983). "A note about paramedics' strategies for dealing with death and dying". Journal of Occupational Psychology 56: 83–86. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8325.1983.tb00114.x.

- ↑ Riessman, Catherine K. (1993). Narrative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- ↑ Gubrium, J. F. and Holstein, J. A. (2009). Analyzing Narrative Reality. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- ↑ Holstein, J. A.; Gubrium, J. F., eds (2012). Varieties of Narrative Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- ↑ Saldana, Johnny (2012). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. Sage. ISBN 978-1446247372.

- ↑ Strauss, A. & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. New Delhi: Sage.

- ↑ Racino, J.; O'Connor, S. (1994). "'A home of my own': Homes, neighborhoods and personal connections". in Hayden, M.; Abery, B.. Challenges for a Service System in Transition: Ensuring Quality Community Experiences for Persons with Developmental Disabilities. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. pp. 381–403. ISBN 978-1-55766-125-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=gnBHAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA381.

- ↑ Krippendorf, K. (1980). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage: Newbury Park, CA.

- ↑ Morning, Ann (2008). "Reconstructing Race in Science and Society: Biology Textbooks, 1952-2002". American Journal of Sociology 114 Suppl: S106-37. doi:10.1086/592206. PMID 19569402.

- ↑ Evans, James (2004). "Beach Time, Bridge Time and Billable Hours: The Temporal Structure of Temporal Contracting.". Administrative Science Quarterly 49 (1): 1–38. doi:10.2307/4131454. https://web.stanford.edu/group/WTO/cgi-bin/wp/wp-content/uploads/2014/pub_old/Evans_2004.pdf.

- ↑ Helfand, Gloria; McWilliams, Michael; Bolon, Kevin; Reichle, Lawrence; Sha, Mandy (2016-11-01). "Searching for hidden costs: A technology-based approach to the energy efficiency gap in light-duty vehicles". Energy Policy 98: 590–606. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2016.09.014. ISSN 0301-4215.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Silver, C., & Lewins, A. F. (2014). Computer-assisted analysis of qualitative research. In P. Leavy (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of qualitative research. (pp. 606–638). Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Lincoln, Y. & Guba, E. G. (1985) Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA:Sage Publications.

- ↑ Teeter, Preston; Sandberg, Jorgen (2016). "Constraining or Enabling Green Capability Development? How Policy Uncertainty Affects Organizational Responses to Flexible Environmental Regulations". British Journal of Management 28 (4): 649–665. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12188. http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/93826/1/WRAP-constraining-enabling-green-policy-flexible-Sandberg-2017.pdf.

- ↑ Lichtman, Marilyn (2013). Qualitative research in education : a user's guide (3rd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4129-9532-0.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Schonfeld, I.S., & Mazzola, J.J. (2013). Strengths and limitations of qualitative approaches to research in occupational health psychology. In R. Sinclair, M. Wang, & L. Tetrick (Eds.), Research methods in occupational health psychology: State of the art in measurement, design, and data analysis (pp. 268-289). New York: Routledge.

- ↑ Katz, D. (1937). Animals and men. London: Longmans, Green.

- ↑ Popper, K. (1963). Science: Conjectures and refutations. In K. R. Popper (Ed.), Conjectures and refutations: The growth of scientific knowledge. New York: Basic Books.

- ↑ Russell, B. (1945). A history of western philosophy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- ↑ Kelly, J.G. & Song, A.V. (Eds.). (2004). Six community psychologists tell their stories: History, contexts, and narrative. Binghamton, New York: The Haworth Press.

- ↑ Farrell, Edwin. Hanging in and Dropping Out: Voices of At-Risk High School Students. New York: Teachers College Press: 1990.

- ↑ Farrell, Edwin. Self and School Sucess : Voices and lore of Inner-city Students. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 1994

- ↑ Murray, M.; Chamberlain, K. (1998). "Qualitative research [Special issue]". Journal of Health Psychology 3 (3): 291–445. doi:10.1177/135910539800300301. PMID 22021392.

- ↑ Murray, M. & Chamberlain, K. (Eds.) (1999). Qualitative health psychology: Theories and methods. London: Sage

- ↑ Gough, B., & Deatrick, J.A. (eds.)(2015). Qualitative research in health psychology [special issue]. Health Psychology, 34 (4).

- ↑ Doldor, E., Silvester, J., & Atewologu. D. (2017). Qualitative methods in organizational psychology. In C. Willig and W. Stainton-Rogers (Eds). The Sage handbook of qualitative research in psychology, 2nd ed. (pp.522-542). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- ↑ Rothman, E. F.; Hathaway, J.; Stidsen, A.; de Vries, H. F. (2007). "How employment helps female victims of intimate partner violence: A qualitative study". Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 12 (2): 136–143. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.12.2.136. PMID 17469996.

- ↑ Schonfeld, I.S.; Mazzola, J.J. (2015). "A qualitative study of stress in individuals self-employed in solo businesses". Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 20 (4): 501–513. doi:10.1037/a0038804. PMID 25705913. https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1277&context=gc_pubs.

- ↑ Schonfeld, I. S., & Farrell, E. (2010). Qualitative methods can enrich quantitative research on occupational stress: An example from one occupational group. In D. C. Ganster & P. L. Perrewé (Eds.), Research in occupational stress and wellbeing series. Vol. 8. New developments in theoretical and conceptual approaches to job stress (pp. 137-197). Bingley, UK: Emerald. doi:10.1108/S1479-3555(2010)0000008007

- ↑ Elfering, A.; Grebner, S.; Semmer, N. K.; Kaiser-Freiburghaus, D.; Lauper-Del Ponrte, S.; Witschi, I. (2005). "Chronic job stressors and job control: Effects on event-related coping success and well-being". Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 78 (2): 237–252. doi:10.1348/096317905x40088.

- ↑ Eriksson, Moa (2015-11-03). "Managing collective trauma on social media: the role of Twitter after the 2011 Norway attacks" (in en-US). Media, Culture & Society 38 (3): 365–380. doi:10.1177/0163443715608259. ISSN 0163-4437.

- ↑ Guntuku, Sharath Chandra; Yaden, David B; Kern, Margaret L; Ungar, Lyle H; Eichstaedt, Johannes C (2017-12-01). "Detecting depression and mental illness on social media: an integrative review" (in en). Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. Big data in the behavioural sciences 18: 43–49. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.07.005. ISSN 2352-1546. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352154617300384.

- ↑ Sloan, Luke; Morgan, Jeffrey; Housley, William; Williams, Matthew; Edwards, Adam; Burnap, Pete; Rana, Omer (August 2013). "Knowing the Tweeters: Deriving Sociologically Relevant Demographics from Twitter" (in en-US). Sociological Research Online 18 (3): 74–84. doi:10.5153/sro.3001. ISSN 1360-7804. http://orca.cf.ac.uk/49152/1/SocResOnline%20Knowing%20the%20Tweeters.pdf.

Further reading

- Adler, P. A. & Adler, P. (1987). : context and meaning in social inquiry / edited by Richard Jessor, Anne Colby, and Richard A. Shweder OCLC 46597302

- Baškarada, S. (2014) "Qualitative Case Study Guidelines", in The Qualitative Report, 19(40): 1-25. Available from [1]

- Boas, Franz (1943). "Recent anthropology". Science 98 (2546): 311–314, 334–337. doi:10.1126/science.98.2546.334. PMID 17794461. Bibcode: 1943Sci....98..334B.

- Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed method approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2000). Handbook of qualitative research ( 2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The SAGE Handbook of qualitative research ( 4th ed.). Los Angeles: Sage Publications.

- DeWalt, K. M. & DeWalt, B. R. (2002). Participant observation. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Fischer, C.T. (Ed.) (2005). Qualitative research methods for psychologists: Introduction through empirical studies. Academic Press. ISBN:0-12-088470-4.

- Franklin, M. I. (2012), "Understanding Research: Coping with the Quantitative-Qualitative Divide". London/New York. Routledge

- Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Gubrium, J. F. and J. A. Holstein. (2000). "The New Language of Qualitative Method." New York: Oxford University Press.

- Gubrium, J. F. and J. A. Holstein (2009). "Analyzing Narrative Reality." Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Gubrium, J. F. and J. A. Holstein, eds. (2000). "Institutional Selves: Troubled Identities in a Postmodern World." New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hammersley, M. (2008) Questioning Qualitative Inquiry, London, Sage.

- Hammersley, M. (2013) What is qualitative research?, London, Bloomsbury.

- Holliday, A. R. (2007). Doing and Writing Qualitative Research, 2nd Edition. London: Sage Publications

- Holstein, J. A. and J. F. Gubrium, eds. (2012). "Varieties of Narrative Analysis." Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Kaminski, Marek M. (2004). Games Prisoners Play. Princeton University Press. ISBN:0-691-11721-7.

- Mahoney, J; Goertz, G (2006). "A Tale of Two Cultures: Contrasting Quantitative and Qualitative Research". Political Analysis 14 (3): 227–249. doi:10.1093/pan/mpj017.

- Malinowski, B. (1922/1961). Argonauts of the Western Pacific. New York: E. P. Dutton.

- Miles, M. B. & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pamela Maykut, Richard Morehouse. 1994 Beginning Qualitative Research. Falmer Press.

- Pernecky, T. (2016). Epistemology and Metaphysics for Qualitative Research. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods ( 3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Pawluch D. & Shaffir W. & Miall C. (2005). Doing Ethnography: Studying Everyday Life. Toronto, ON Canada: Canadian Scholars' Press.

- Racino, J. (1999). Policy, Program Evaluation and Research in Disability: Community Support for All." New York, NY: Haworth Press (now Routledge imprint, Francis and Taylor, 2015).

- Ragin, C. C. (1994). Constructing Social Research: The Unity and Diversity of Method, Pine Forge Press, ISBN:0-8039-9021-9

- Riessman, Catherine K. (1993). "Narrative Analysis." Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Rosenthal, Gabriele (2018). Interpretive Social Research. An Introduction. Göttingen, Germany: Universitätsverlag Göttingen.

- Savin-Baden, M. and Major, C. (2013). "Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice." London, Rutledge.

- Silverman, David, (ed), (2011), "Qualitative Research: Issues of Theory, Method and Practice". Third Edition. London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi, Sage Publications

- Stebbins, Robert A. (2001) Exploratory Research in the Social Sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Taylor, Steven J., Bogdan, Robert, Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods, Wiley, 1998, ISBN:0-471-16868-8

- Van Maanen, J. (1988) Tales of the field: on writing ethnography, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Wolcott, H. F. (1995). The art of fieldwork. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Wolcott, H. F. (1999). Ethnography: A way of seeing. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Ziman, John (2000). Real Science: what it is, and what it means. Cambridge, Uk: Cambridge University Press .

External links

| Library resources about Qualitative research |

- Qualitative Philosophy

- C.Wright Mills, On intellectual Craftsmanship, The Sociological Imagination,1959

- Participant Observation, Qualitative research methods: a Data collector's field guide

- Analyzing and Reporting Qualitative Market Research

- Overview of available QDA Software

Videos

|